Community Events

Community events are: Centred around the concept of community; typically planned by individuals, groups, or organisations based in and familiar with the identity of the host community; and largely shaped by and rooted in the community’s culture, traditions, context, people, history and geography. Community events are also traditionally open to the public through either an open-access format or some sort of registration or ticketing process, and often feature programming that generates collective experiences aligned with a community’s identity.

Community events can include but are not limited to concerts, festivals, parades, sporting events (competitive and recreational), farmer and artisan markets, commemorative ceremonies, fairs, and street parties. Often difficult to categorise singularly by scope, size, scale, format or features, the value and benefits community events bring to their host location and residents more commonly define them.

Stakeholders

Community event stakeholders are any person, group, organisation or entity that is or perceives themselves to be directly or indirectly impacted by the activities or outcomes of the planning or execution of a community event.

Appropriately identifying event stakeholders and understanding the role they play within a community event’s dynamic is an important responsibility of a community event organiser and critical to developing and maintaining constructive stakeholder relationships.

Event stakeholders are typically defined under one of three categories – primary, secondary, and tertiary – based on:

- Their relationship to or involvement with the event,

- The level of their individual power and influence over the event’s activities or outcomes,

- The level of their individual interest in one or more event activities or outcomes, and

- The degree to which they may be impacted by the event’s activities or outcomes.

The nature and focus of a stakeholder’s involvement, power, influence, interest and impact can depend on factors including their role and position in the community, financial or business interests, moral or cultural values, political influence, and/or demographics, to give a few examples.

Categories of Stakeholders

1. Primary stakeholders

A primary stakeholder generally defines any person, group, organisation or entity that has direct involvement with the activities or outcomes of a community event. These stakeholders are typically heavily invested in the event planning process and are usually directly impacted by the event’s activities or outcomes. Primary stakeholders usually hold significant power, influence and interest in the event planning and delivery processes.

Examples of community event primary stakeholders include the event organiser, event team members, event sponsors, participants, grant funding representatives, key talent or entertainers, volunteers, and engaged community members including the local mayor, dignitaries and business owners.

2. Secondary stakeholders

Secondary stakeholders are generally people, groups, organisations or entities involved with a community event that hold less power, influence and interest than primary stakeholders. Secondary stakeholders are usually more indirectly affected by the event’s activities or outcomes.

Examples of secondary stakeholders include service providers that provide support to event activities such as equipment rentals, hotel accommodation, ground transportation, tourists and local residents.

3. Tertiary stakeholders

Tertiary stakeholders are generally people, groups, organisations or entities that are removed from but are still impacted by event planning activities or outcomes. Tertiary stakeholders can be considered external stakeholders and usually hold very little power, influence or interest in an event’s planning or execution processes. In some contexts, tertiary stakeholders are identified because of their subject matter expertise (SME) or their role as advisors, consultants or advocates for a specific community event.

Examples of community event tertiary stakeholders may include event association or network members, SME professionals, lobbyists, or industry consultants.

Stakeholder Matrices

There are a variety of stakeholder matrices used in industry to categorise, define and analyse the role and position of event stakeholders.

A simple stakeholder categorisation matrix as pictured in the table below identifies the three common stakeholder categories, along with their respective levels of power, influence, interest and degree of impact sustained from the event.

| Stakeholder Type | Power | Influence | Interest | Degree of Impact by the Event |

| Primary | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH | HIGH |

| Secondary | MODERATE-LOW | MODERATE-LOW | MODERATE-LOW | MODERATE |

| Tertiary | LOW | LOW | LOW | LOW |

Table 8:1 Simple Stakeholder Classification Matrix

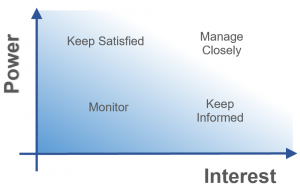

A more analytical stakeholder matrix is the Power-Interest Matrix. This matrix is often used to plot the amount of stakeholder power, which is the ability of a stakeholder to influence change within the event, against the amount of stakeholder interest. It also plots the alignment between the stakeholder and the event’s shared goals in order to understand how best to manage and communicate with an individual stakeholder or group (Roseke et al., 2019).

Stakeholders with high power and high interest are primary stakeholders that are heavily invested in the event and should be actively managed.

Stakeholders with high power but low interest should be kept satisfied as they may cause adverse impacts.

Stakeholders with low power but high interest should be kept informed as they can have great influence to obtain outcomes that serve their own interests.

Stakeholders with low power and low interest should be monitored in case they gain power over time and come to impact the event in the future (Roseke et al., 2019).

Community Special Event (Advisory) Team (SEAT/SET)

While the composition and function of municipal SEAT/SET teams vary somewhat by municipality, most often this group is comprised of municipal, regional and service agency members responsible for reviewing and/or approving community event applications.

A municipal SEAT/SET team may include staff from the following departments or agencies:

- Building Services

- Bylaw Enforcement

- Communication Services

- Corporate Security

- Cultural Services

- Economic Development

- Emergency Medical Services

- Event Services

- Fire and Emergency Services

- Health and Safety

- Legal Services

- Paramedic / First Aid Services

- Parks / Facility Operations

- Police Services

- Public Health

- Recreation Services

- Risk Management

- Road Operations

- Transit services

Engaging these stakeholders early in the process of planning a community event is important to ensuring compliance with any regulations and best practices relating to the event elements planned.

Common community event stakeholders

Establishing a working group of internal staff and/or volunteers, supplier contacts and local community stakeholders is an important first step in the community event planning process.

Primary Stakeholders |

Secondary Stakeholders |

Tertiary Stakeholders |

| Event organizer & event team members | Service providers & contractors | Advisors & consultants |

| Event sponsors & grant funding representatives | Local residents | Advocates & lobbyists |

| Participants & attendees | Visitors & tourists | Subject matter expert professionals |

| Key talent or entertainers | Industry association or network members | |

| Volunteers & engaged community members | ||

| Local political representatives (all levels) | ||

| Municipal Special Event Advisory Team staff |

Table 8:2 Common community events stakeholders by category

Benefits and Challenges

The benefits and challenges of community events are just as broad and diverse as the events themselves. The PESTEL framework is commonly used to “analyse and monitor the macro-environmental factors that may have a profound impact on an organisation’s performance” (PESTEL analysis, 2020). A PESTEL framework (PESTEL analysis, 2020) is useful for identifying and categorising the value, benefits and challenges of community events both generally and individually. The PESTEL acronym stands for Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental and Legal factors that influence or represent impacts on an organisation, operation, or event.

To help identify and categorise the value and benefits of community events, the traditional PESTEL framework is modified below, replacing the ‘Political’ factor with ‘Personal’ and eliminating ‘Legal’ considerations for simplicity. While specific community events may have both political and legal impacts, the more common indicators of an event’s value are captured in the table below.

In this table, the benefits presented may be direct or indirect impacts had by an event on individual event stakeholders (i.e. attendees, community members, etc.) or collective stakeholder groups (i.e. host community, neighbourhoods, etc.).

PESTEL Analysis: Common Benefits of Community Events |

||||

| PERSONAL | ECONOMIC | SOCIO-CULTURAL | TECHNOLOGICAL | ENVIRONMENTAL |

| Physical health;

Individual and collective happiness and well-being; Relationship development; Positive mental health impacts; Memory-making. |

Visitation and patronage;

Supporting local business and vendors; Tourism; Employment opportunities; Accommodation tax revenue; Sponsorship opportunities; Grant funding. |

Community cohesion;

Participation and volunteering; Inclusion; Maintaining traditions; Collective knowledge and storytelling; Preservation of culture, history and traditions. |

Innovation;

Automation; Skills training; Public/private partnerships. |

Sustainability;

Green mandates; Corporate social responsibility; Environmental protection; Cost reduction; |

Table 8:3 Common benefits of community events

The same modified PESTEL framework can identify common challenges caused by or related to community events.

In this analysis, the challenges presented may bear either first-person and/or third-party impacts on event stakeholders (i.e. event organisers, event team members, event attendees) or collective stakeholder groups (i.e. host community, neighbourhoods).

PESTEL Analysis: Common Challenges of Community Events |

||||

| PERSONAL | ECONOMIC | SOCIO-CULTURAL | TECHNOLOGICAL | ENVIRONMENTAL |

| Long hours;

Difficulty maintaining work-life balance in the event planning process; Succession-planning for staff and volunteer turnover. |

Increasing costs related to event requirements and regulations

Limited access to / high competition for public and private funding; Effects of weather on onsite event revenue streams (i.e. rain = low vendor sales); Tight profit margins; Annual fluctuations of sponsorship availability. |

Maintaining institutional knowledge of community events as committees change;

Balancing tradition with progress and evolution; Maintaining inclusion in standardised event formats; Resistance to change. |

Potential costs of investing in new technologies;

Acquisition costs of using new systems (staff training, equipment); Difficulty maintaining systems within volunteer-led organisations. |

Generation of significant waste by events;

Financial and logistical limitations of temporary waste management programs; Temporary nature of events generates increased demand for travel, transportation, storage, and material use. |

Table 8:4 Common challenges caused by or related to community events

Placemaking

Placemaking is defined as “both an overarching idea and a hands-on approach for improving a neighborhood, city, or region, …[and] strengthening the connection between people and the places they share” (RSS., n.d.). A wealth of studies and literature cite community events as critical activities that support placemaking practices and benefits. Under Placemaking Theory, community events can define and enhance a community’s key attributes (i.e. sociability, comfort, image), intangible qualities (i.e. cooperation, vitality, celebration), and measurable data (i.e. social networks, volunteerism, land use patterns). Many of the common benefits of community events identified in the PESTEL table above, such as participation, volunteering, and relationship development, further the practice of placemaking.

The interrelationship between community events and placemaking is widely recognised among community event professionals.

The mindset of real community purpose is not only of significant importance to those developing spaces: Placemaking and events go hand in hand. Those in the events industry are experts in creating temporary spaces that bring people together. Events bring spaces to life—this is fundamental to successful placemaking. Events have audience experience at the heart of everything they do, creating temporary destinations which forge a relationship between the space and the temporary community within it as well as, of course, reaching internal commercial objectives and laying the foundations for repeat visits. The developments’ brand and purpose should be reflected in their live event offering which means that they can become synonymous with specific live events that reflect who and where they are.

This in turn bolsters their offering as a space and the direct impact on their local community as a place. The events industry has the experts who make this happen and for placemaking to be successful, the feasibility for a space to act as both a practical space for events as well as an enhancement to the surrounding environment and community is key (Roxy, 2018).

Municipal governments are also champions of placemaking, both as organisers of community events and as facilitators and funders of community-led initiatives that often take place on municipal property and further municipal mandates. To support the revitalisation of public spaces and community engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic, the City of Hamilton in Ontario, Canada recently launched a Placemaking Grant Pilot Program (City of Hamilton, 2020). Targeting groups and individuals interested in developing placemaking projects between 2021-2023, the program provides financial support to initiatives delivering placemaking goals including “opportunities to get to know people in your community, feel welcomed and comfortable, [and create] a sense of ownership and pride” (City of Hamilton, 2021, p. 3). The program is accompanied by a Placemaking Toolkit (City of Hamilton, 2021) which sets out the fundamental principles of placemaking and outlines a selection of municipal event planning, permitting and regulatory requirements for organisers. While not all placemaking activities are events, the delivery of placemaking activities often follows many event planning practices and principles as explored later in this chapter.

The delivery of successful placemaking activities can evolve into something of a movement across communities. Initiatives such as 100 in 1 day Canada illustrate how placemaking efforts that become popular in one community are frequently adopted in others. The Love My Hood program is another example of a local placemaking initiative with considerable uptake across Ontario.

Case Study: Love my Hood

Launched by the City of Burlington in Ontario, Canada in 2016, the Love My Hood program was “designed to build a healthier Burlington by engaging and empowering residents to come together and provide events celebrating their Burlington neighbourhoods” (Staff, 2017a). The program provided resources (i.e. garbage cans, barricades and basic recreational equipment), administrative support through the municipal event permitting process, and funding up to $300 to help eliminate common barriers in community event hosting (Staff, 2017a). Having supported hundreds of neighbourhood-led community events in Burlington, including 150 events in 2017 to mark the celebration of Canada’s 150th anniversary (Staff, 2017b), Love My Hood has been adopted and expanded by other Ontario municipalities, including the City of Kitchener.

Kitchener’s Love My Hood program is “both a [neighbourhood] strategy for the City of Kitchener and a movement led by residents” (About love my hood, 2021). The program “encourages residents to take the lead in shaping their neighbourhood with help from the city. Residents choose the projects that matter most to them and decide how to shape the future of their neighbourhood” (About love my hood, 2021). Kitchener’s program enables a multitude of placemaking activities including porch parties, boulevard beautification, community gardens, little libraries, markets, public seating and public art through the resourcing of guides, toolkits, grants and funding. Having expanded on Burlington’s original Love My Hood concept, Kitchener’s Love My Hood program leverages community event planning practices to enable “the best neighbourhoods [to be made by] the people who live in them” (About love my hood, 2021).

Tourism

Generally, community events offer all attendees unique leisure, recreational, social and cultural experiences such as trying new food, enjoying new entertainment, and exploring different destinations. From this perspective, many community events are tourism motivators, offering reasons for visitors to travel to and experience new places, peoples and practices.

In Canada, the operational definition of tourism is defined as “same-day trips that are ‘out of town’ and forty kilometers or more one way from home and all overnight trips that are ‘out of town’” (Appendix A, 2015). By this definition, event attendees that travel greater than 40 kilometers or who attend a community event as part of an overnight trip are tourists. The economic benefits tourist attendees bring to an event’s host community define the tourism value of a community event.

Through the attraction of both resident and tourist attendees, community events demonstrate tourism value by directly and indirectly increasing patronage to local businesses, generating local employment opportunities, increasing awareness of local services and destinations, and creating collective experiences that become synonymous with a community’s identity. Direct tourism benefits of community events also more specifically include increased revenue to the community generated through the charging of Municipal Accommodation Tax (MAT) fees by local restaurant and hotel operators and efforts to raise awareness for unique local offerings that compel return tourist visitation and patronage after the event and throughout the year.

In support of the tourism-related economic benefits offered by community events, many municipal, provincial and federal governments offer tourism grant programs which fund community events. These programs such as the Province of Ontario’s 2021 Reconnect Festival and Event Program (Government of Ontario, 2021) provide application-based funding allocations to offset prescribed tourism-generating event planning costs such as dedicated marketing and promotions targeted at attracting tourist visitors from outside a 40-kilometer radius.

Hyper-local events

Many community events intentionally engage specifically local audiences rather than out-of-town visitors. Activities such as farmer’s markets, park openings, flag raisings, memorial celebrations, and localised cultural or community holiday celebrations are examples of ‘hyper-local’ community events. In the community context, hyper-local events appeal to or engage a specific local audience demographic.

Determining whether a community event will be locally focused or a tourism driver is usually an effort undertaken by the event organiser when developing the event’s goals, objectives and key performance indicators (KPIs) at the outset of the event planning process. The strategic selection of an event’s entertainment line-up, design of activities, location, and targeted efforts to intentionally include or limit specific logistical supports such as parking availability, transportation access, and promotional efforts often influence the event’s position as local or tourism-focused.

For example, a ceremony to unveil the opening of a local park featuring entertainment by students from a neighbourhood music school and speeches from local dignitaries is unlikely to be of interest to tourists, but it may attract local residents and future park users. Alternatively, a local pie festival occurring over a long weekend featuring delicious pie-themed programming like a pie-baking competition with submissions by well-known regional chefs, nationally recognised musical performers on the main stage, and a free transportation shuttle bringing visitors to and from the festival from the local train station is more likely to attract tourist visitors.

The probability of a similar event occurring in a neighbouring community can also influence the categorisation of an event as hyper-local. Generally, community events such as seasonal farmer’s markets, Victoria Day fireworks shows, Pride Month celebrations, Remembrance Day ceremonies, and Santa Claus parades commonly occur in most Canadian communities. As such, while there may be a small number of visiting friends and relatives (VFR) tourists attending these local events, such events tend to feature hyper-locally focused entertainment and are generally very similar in nature and format from one community to the next.

Event classification

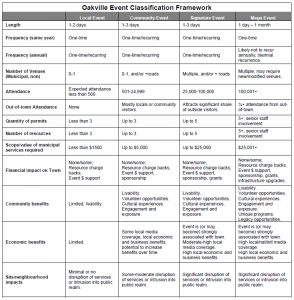

The act of defining or classifying community events is helpful for establishing a common understanding for the nature, impact and requirements of each type of community event. As explored above, classifying events solely in accordance with their scope, size, scale, format or location can limit capturing important details about an event’s overall impact.

Municipal staff often use event classification frameworks to estimate the levels of administrative and operational impact an event has or is expected to have on the municipality’s event management processes and to inform decisions related to event operational policies and logistical processes. Typically, no single criterion individually determines the classification of an event. Rather, an event classification process defines an event according to the category that best represents the majority of factors or considerations presented by it. While individual interpretations of an event classification framework’s categories can vary, the use of an event classification framework is helpful to developing and maintaining standardised event support processes, policies and practices.

Signature Events

In industry terms, ‘Signature events’ tend to denote two classifications community events:

- A high-profile community event known locally for its significance to the community’s identity, legacy/tradition, or reputation, and usually of considerable scope, size or scale.

- A high-profile community event known more broadly, often provincially or nationally, for its significance to the community and society as a whole.

These two classifications are not mutually exclusive and can be further defined using a variety of parameters including: Number of attendees, duration, economic impact, number of venues used, and number of permits required.

Event stakeholders including attendees, visitors, community residents, sponsors, suppliers, and municipal support staff each tend to bestow signature event status using different variables for different reasons. A community resident may consider a community event signature because it has taken place for many years (or decades) and they attend each year as a personal tradition. A corporate event sponsor may consider a community event to be signature because they allocate the greatest percentage of their annual sponsorship budget to funding the event, and have developed a strong relationship with the event committee. In order to determine when and how to leverage a community event as a signature event, the event organiser should maintain a keen understanding of the event’s specific logistical details and work to build strong relationships with all of the events key stakeholder groups.

Case Study: Carrot Fest – Bradford West Gwillimbury, Ontario

Carrot Fest is a two-day street festival located in Bradford West Gwillimbury, Ontario. Featuring a variety of entertainment including BMX bike and dog shows, a Kids’ Zone, beer garden and street festival with over 200 street vendors, Carrot Fest celebrates Bradford West Gwillimbury as one of Canada’s biggest carrot-producing regions and bills itself as “The World’s Greatest Carrot Festival!” (Town of Bradford West Gwillimbury, 2021).

With roots dating back to the mid-1970s, Carrot Fest was historically planned by a local community-led committee with a mandate to promote tourism, economic development and downtown revitalisation. In 2005, the Town of Bradford West Gwillimbury assumed responsibility for organising and running the event. Since then the number of attendees has quadrupled to an estimated 50,000 participants, generating $1 million for the local economy and winning the ‘Top 100’ award from Festivals and Events Ontario.

Carrot Fest is a good example of a signature community event known locally for its significance to the community’s identity, legacy and tradition. However, due to the regional nature of the festival’s thematic relevance and programming, its signature event status likely does not apply broadly beyond the festival’s regional area (Town of Bradford West Gwillimbury, 2021).

Case Study: Calgary Stampede in Calgary, Alberta, Canada

The Calgary Stampede got its start in 1886 as the Calgary District and Agricultural Society Exhibition. Created to share knowledge about practicing agriculture and to showcase ‘the best of the West’, the Exhibition became an annual event and attendance continued to grow steadily through the end of the 1800s. The first official Stampede took place in 1912, drawing 80,000 people. Throughout the 1900s the Stampede became a focal point in Calgary’s community event schedule featuring a rodeo, parade, pancake breakfast, and numerous celebrations. Through programming changes, property developments and both World Wars, the Stampede solidified itself as a community gathering space, long committed to educating the community about agriculture (Chapter One The Early Years 1886-1912, n.d.).

The City of Calgary has widely embraced the Stampede. The event is home to school trips, hockey games, figure skating during the 1988 Winter Olympics, and even hosted the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge in 2011. Between 1912 and 2015, 67,729,617 people attended the Stampede, and today, the Stampede has over 2500 volunteers and has earned acclaim as a Canadian signature event (Chapter Three Building the Stampede! 1946-2011, n.d.).

Delivery models

Community events typically occur under one of four delivery models as outlined in the table below. Factors including the composition of the event organisers or parent organisation, the ownership status of the property on which the event occurs, and the event’s target audience type traditionally define these delivery models.

|

COMMUNITY EVENT MODEL |

ORGANISER |

PROPERTY CLASSIFICATION |

AUDIENCE |

| Municipally-planned | City/town staff | Public property | Local residents and/or tourists |

| Community-planned | Local resident, group, or non-profit organisation | Public or private property | Local residents and/or tourists |

| Privately-planned | Private individual, business, or venue | Public or private property | Local residents and/or tourists |

| Hybrid | A partnership of two or more organiser types | Public or private property | Local residents and/or tourists |

Table 8:6: Community event delivery models

Further variations or hybrid assemblies of these delivery models can exist, though variations on the models presented typically define non-community events.

Governance

Events in Canada do not have a central governing body responsible for policy development, oversight or regulatory compliance.

As such, the following table itemises the various levels of Canadian government agencies with jurisdiction over factors that influence community event planning regulations, requirements and best practices.

|

Federal Government |

Jurisdiction / Event Planning Considerations |

|

Health Canada |

Federal public health guidelines |

|

Provincial Government(s) |

Jurisdiction / Event Planning Considerations |

|

Provincial Office of Emergency Management [varies by province] |

Provincial public safety guidelines |

|

Provincial Public Health authority [varies by province] |

Provincial public health guidelines |

|

Provincial Ministry of Labour (MOL) [varies by province] |

Provincial safe work regulations |

|

Provincial Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB) or equivalent [varies by province] |

Provincial workplace insurance coverage |

|

Alcohol and Gaming/Gambling authority [varies by province]

|

Provincial alcohol sales and service regulations; Provincial gaming/gambling regulations (including fundraising regulations) |

|

Occupational Health and Safety Act (OHSA) [varies by province] |

Provincial safe work regulations |

|

Local Public Health authority/department |

Local public health regulations (including food service and public sanitation guidelines) |

|

Local first response service(s): Police, Fire, EMS |

Local public safety operations and emergency response |

|

Local Event Permitting Office |

Local special event regulations and permitting processes |