Organising the field: Key branches and orientations within cultural mapping

For most people engaged in cultural mapping, their focus understandably tends to be on the task at hand, without extensive self-reflection on the place of the mapping in the larger field of practice. Social activists, for example, are intent on challenging received systems of authority and power, while policy-makers focus their attention on identifying and nurturing creative industries and development. Cultural planners seek ways to make local culture more visible and engage communities in participatory decision-making, artists emphasise the aesthetic and seek to provide new perspectives and ways of seeing, academics bring a research lens and methodological rigour to refine cartographic practices generally, and people from all walks of life are motivated to locate their interest in art objects and art-making as ‘mappable’ pursuits. Given the diversity of motives and approaches, it is helpful to provide a bird’s eye view of the field. Here, we present you with two organising schemas. First, we note that cultural mapping has been evolving along two main branches, corresponding to “ideal types”: (1) cultural resource/asset mapping and (2) ‘humanistic’ mapping approaches. Second, we point to three general orientations within cultural mapping, organised by each project’s main thematic focal point.

Two “ideal types”

As the number of cultural mapping projects has grown and they have become more visible, two “ideal types” of projects have become evident: cultural resource/asset mapping and ‘humanistic’ mapping approaches. This general organisation has influenced the way the field sees and defines itself, as well as the ways in which efforts are applied to advance methodological practices in each of these areas.

Cultural resource/asset mapping

This first branch begins with cultural assets. It seeks to identify and document tangible and intangible assets of a place with the aim of developing and incorporating culture and creative industries in strategies that address broader issues of a locale. In this context, a general distinction has often been made between asset mapping and identity mapping. This division typically distinguishes between physical or tangible cultural assets—cultural venues, public art works, historic sites, monuments, and identifiable organisations and persons—and intangible assets which provide a sense of place and identity for a locale and can incorporate both historical and contemporary aspects. As examples, UNESCO defines intangible cultural heritage as including “oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts” (UNESCO, n.d.). Contemporary intangible cultural aspects can also include artistic and craft skills and expressions specific to a place, and informal social arrangements that enable cultural/artistic knowledge and know-how to be shared. Over time, tangible and intangible dimensions have become increasingly intertwined and are, more and more, considered together.

Three examples of mapping projects focused on cultural resource/asset mapping from Brazil, South Africa, and the United States follow.

Cultural sector mapping examples:

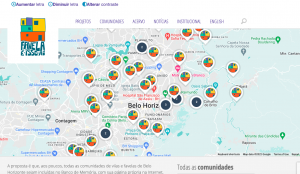

.Favela é Isso Aí, Belo Horizonte, Brazil

Between 2002 and 2015, the non-governmental organisation Favela é Isso Aí led a series of cultural mapping experiences in the slums (the favelas and villages located on the city margins) of Belo Horizonte, Brazil. The projects began with the development of the Cultural Guide of Villages and Favelas, which was published in 2004. The Guide highlighted that art in the villages and favelas has a special part on raising self-esteem, social inclusion, and decreasing violence. The cultural mapping processes were organised together with associations and residents of these territories, oriented to local objectives and to effectively engage the participation of residents. They were designed and implemented as a tool to access the multiple and complex cultural and symbolic realities of the communities. The initiatives were guided by the contention that culture is a key to the constitution and reconstruction of identities, rescuing self-esteem and political agency and addressing the recurrent social marginalisation and depreciation processes these populations undergo. The mapping of the slums—and the widespread dissemination of the results—has leveraged personal, social, and political transformations within the communities. Even after the end of the projects, the cultural mapping work continued to have an extended effect, contributing to the constitution of what is now an ongoing search for change of intertwined social and urban issues through cultural practices and activism. As Clarice Libânio has written,

In the slums of Belo Horizonte (and similar situations reported in other Brazilian slums), culture has an important role in overcoming the challenges of inequality so that lower-income populations have access and seek effective rights to the city. These territories also demonstrate the importance of culture as a transformative, mobilising agent in increasing education levels through the engagement of (mostly) young citizens in cultural activities, gaining a better worldview through non-formal education, and establishing external relationships with new social groups.

Since the launching of the Guide, the slums and their residents began to be seen in a different way—by other city residents and by the communities themselves. Cultural mapping altered the place of the slums in the city and in the public policies, and changed internal and external visions, which contributed to transformation, new actions, and bridge building. The mapping process was catalysed by the artists and their works and as such called for something other than an objectifying mode of documentation, in this case the creation of an occasion for pedagogical and dialogical exchange. The mapping turned out to be a resource that enabled action and amplified the community’s voices. (Libãnio, 2019, p. 174).

“Beyond the Radar, Plotting New Cultural Ecosystems” project, The Trinity Session, Johannesburg, South Africa

This project, launched in 2020, aims to create collaborative networks between a range of multidisciplinary organisations in order to support existing projects and identify new innovations happening specifically in the Northern Cape and Mpumalanga. The first phase of the process has involved identifying key organisations and individuals active in the fields of environmental, social, digital, cultural, and creative practice and knowledge production. Once potential project areas and actors within given networks are identified, the project will conduct a series of facilitated online workshops which will lead from introductions among the cultural actors identified in the mapping process to considerations of history, place, and potential futures; experimentation and testing of ideas for stimulating existing and new projects; and exploring ideas for co-production through digital platforms.

Los Angeles, United States | Promise Zone Arts

Promise Zone Arts (PZA) is a two-year, multi-neighborhood cultural asset mapping and activation initiative administered by the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs and co-created by the Alliance for California Traditional Arts and LA Commons. The project seeks to illuminate the value of neighborhood cultural assets from the perspectives of residents, and make the cultural treasures they identify visible and recognisably essential to holistic sustainability. It utilises cultural mapping strategies, ethnographic documentation, community gatherings, and free public events to identify and support the artists, cultural practitioners, tradition bearers, and sites that Los Angeles Promise Zone neighborhood residents deem significant. The target neighbourhoods are located in Central Los Angeles and include East Hollywood (Little Armenia, Thai Town), Hollywood, Koreatown, and Westlake/Pico Union.

PZA has four core components:

- A Participatory Cultural Asset Mapping process to facilitate resident engagement in identifying neighborhood cultural treasures, which is led by partner organisations the Alliance of California Traditional Arts and LA Commons;

- Recording and Documentation of Cultural Treasures to archive the stories and traditions discovered through the cultural asset mapping process and add them to a research database;

- The development of a Public Digital Cultural Treasures Storybank showcasing underrepresented cultural assets and traditional and folk artists to provide exposure and opportunity; and

- Free Cultural Treasures Celebrations with local artists and interactive performances as well as traditional foods from the diverse Promise Zone communities.

‘Humanistic’ mapping approaches

The second branch of cultural mapping, associated with the rise of critical cartography (Dodge, Kitchin, and Perkins, 2009), begins with a culturally sensitive, humanistic approach to understanding specific issues of a place, creating a multivocal platform for discussion and finding community-based solutions. The focus is centred on the people who are resident, living, and interacting within a territory: It is their knowledges, experiences, movements, and memories that become integral to defining the cultural assets and meanings of the territory. The topics being examined and mapped can include both tangible and intangible elements. Artistic approaches within this branch can help to articulate the felt sense of place that traditional mapping approaches often miss. Artists can also help foreground the aesthetic dimensions of a community’s self-expression and identity.

While the former approach tends to emphasise the documentation of information and the development of cultural or creative sector intelligence, the latter tends to focuses more on participation and meaning. However, they are not mutually exclusive and are increasingly blended and mutually informing approaches. Taken together, the two areas of cultural mapping seek to combine the tools of modern cartography with vernacular and participatory methods of storytelling to represent spatially, visually, and textually the authentic knowledge, assets, values, views, and memories of local communities.

Humanistic Mapping Examples:

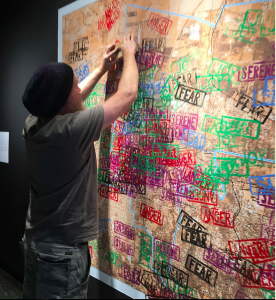

Five Weeks in Spring: an emotional map of Lilydale

The artist-led participatory project Five Weeks in Spring: an emotional map of Lilydale investigated and gathered the emotions that community members associated with different places in their locale, a residential area that had been impacted by forest fires and other impacts of climate change in southern Australia. The gallery map collectively recorded individual emotions associated with particular sites, with the process of gathering and documenting these was imbued with the sharing of numerous personal stories. As Marnie Badham writes,

Five Weeks in Spring aimed to register local citizens’ emotions in response to the changing natural environment. After workshopping the ideas, words and colours with patrons of the local library over a number of weeks, we transferred individual map data on the large wall map. As the artwork became covered by the layering of boldly coloured brick sized stamps, it became increasingly difficult for visitors to locate themselves. But we could clearly see the areas of contention – fear of bush fires and winds, joy felt in parks and the natural environment, anger about rapid business development, sadness about loss of public space and so on… There were mixed emotions and nostalgia was expressed through stories and even debates between residents raised about environmental concerns and extreme weather events. (Badham, 2018).

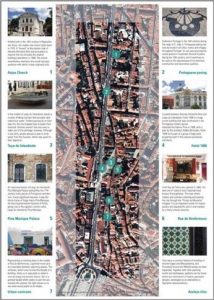

STEPS Pilot: Lisbon, Portugal (Intercultural Cities Programme, Council of Europe)

The Council of Europe’s Intercultural Cities (ICC) programme is based on the idea that “a sense of belonging to an intercultural city cannot be based on religion or ethnicity but needs to be based on a shared commitment to a political community. Accepting that culture is dynamic and that individuals draw from multiple traditions is one of the main operational points of the ICC’s framework.” The STEPS project, “Participatory cultural heritage mapping at a neighbourhood scale,” was a two-year project (December 2016 to December 2018) that explored participatory approaches to cultural heritage as a resource for community development and cohesion. In other words, the project objective was to foster community cohesion through participatory mapping of cultural heritage. The project involved three main steps: Heritage-mapping and needs assessment in relation to community cohesion; network mobilisation, training, and heritage-based strategic planning; and developing perception change indicators and monitoring results through an initial and final survey.

STEPS promoted the idea of participatory mapping of cultural heritage, where members of the community were given the role to identify those material and immaterial cultural assets that are a reflection and expression of their constantly evolving values, beliefs, knowledge, and traditions. Through the participatory mapping process, the community identified a set of resources of value (intangible) to be kept for future generations, which combat a traditional understanding of cultural heritage as a set of objects (tangible). Participatory mapping was viewed as a process, not a product. Participatory processes were nurtured by building confidence, avoiding stereotypes, and recognising the role and expertise of each person involved in the process. This was important for building and growing trust between the different partners, mappers and the diverse participants. This project also illustrates how a commitment to regularly replicating participatory mapping is valuable to keep cultural heritage alive, include newcomers to the community, and renegotiate shared visions.

Three orientations

We can observe three general orientations within cultural mapping, characterised by the main focal point of a project rather than the nature of the types of items that are mapped. These orientations combine the motive and purpose of each mapping project, and can be categorised as follows: (1) Self and place, (2) community attachments to place, and (3) culture(s) of place. These orientations may incorporate methodologies and practices from both the cultural resource/asset mapping approach and the humanistic approach described above.

Self and place

In these projects, the mapper focuses on personal attachments and connections between an individual and a place. The “self” may be themselves or another person. The mapping includes recording not only travel routes but may also explore personal feelings, impressions, memories, and other place-specific narratives and connections. While the focus is on individual stories and experiences, the compilation of multiple individual maps can create a collective sense of a place. Furthermore, informed by journey mapping approaches in health care and business, cultural mapping practices have been applied to other social issues.

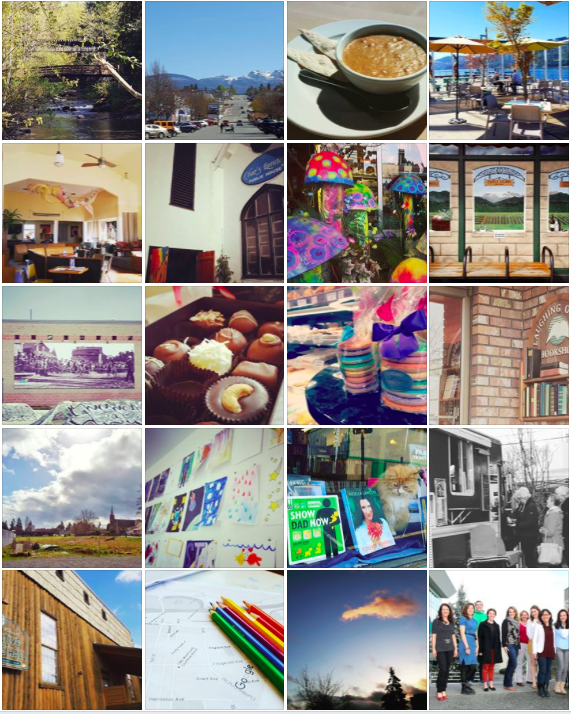

For example, two projects led by local art galleries and working with universities give voice to individual experiences and a highly personal sense of place. The Walk with Me project aims to deepen and personalise experiences of the drug overdose crisis in small towns in British Columbia (see Figure 4:8).

The Salmon Arm Pride Project provides an intimate exploration of personal safety for LGBTQ+ people in terms of their movement through their city (see Video 4:4).

Video 4:4. Overview of the Salmon Arm Pride Project

Community and place

Projects in this category focus on relations between a collective of people and the territory they inhabit, and on how places are meaningful to the communities that live there. They aim to characterise the connection between culture, territory, and the people who live there. The knowledge collected can be collective in nature—that is, without enabling individualised extractions—or can be a pluralistic compilation of individual voices to provide collective messages and impressions, highlighting shared commonalities and differences. They can articulate the face(s) of a community.

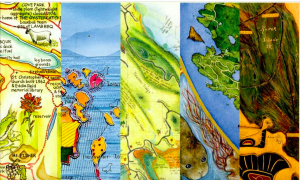

For example, the Islands in the Salish Sea artist-led project enabled a wide range of residents across the islands to record in maps the places and dimensions of their island home-place that are meaningful to them. The participatory project resulted in hundreds of individual maps – in the form of drawings, paintings, and other media – that were then brought together into travelling exhibitions and an illustrated book of a selection of the maps. As is written in the book from this project,

Maps like these express the interior of a place …. They offer an outward portrait of a local intimacy, providing an opportunity to share, to empathise, to know and to care. They are a collective portrait of a community—a face—expressed beautifully and lovingly, with all the lines and marks of experience and age. (Harrington and Stevenson, 2005, p. 19)

They also articulate and mobilise individual knowledges to collectively make local knowledge visible and empower residents. The maps enabled local residents to document and communicate what was special to them about each island (and the islands collectively) to the provincial government and other agencies who were responsible for planning and making decisions about future developments on the islands. This personal, lived knowledge was only available through the people who lived there and cared for these places, and the cultural mapping project enabled this knowledge and these perspectives to be documented and shared.

A second example: In the “Where is Here: Small Cities, Deep Mapping and Sustainable Futures” project, researchers fostered the active participation of local citizens, business owners, municipal development leaders, arts and culture associations, and Indigenous groups to identify the assets and values associated to the places and spaces within the downtown areas of three small cities on Vancouver Island, British Columbia: Nanaimo, Port Alberni and Courtenay. The project responded to the need, expressed by planners and municipal developers, for more dynamic cultural mapping processes at the small city level. The mapping process revolved around three public engagement events or “walk abouts” during which 85 videos were captured of residents speaking of and at the places where they felt most connected to in their downtown core. The videos collectively uncovered layers of meaning associated with a variety of downtown places, highlighting the value of leisure activities and their related use of and engagement with places and spaces in the city. The project provided residents the opportunity to share their “stories of place” and what connects them to the communities they live. These shared stories uncovered a wealth of knowledge about these places and this knowledge, once known and mapped, can lead to more informed place-making efforts (Vaugeois et al., 2016).

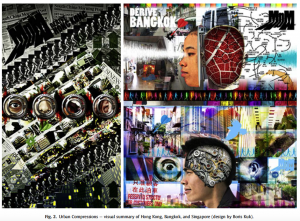

Culture(s) of place

These projects attend to the cultural dimensions and aspects particular to a locale that make it distinct or significant. While also examining people-place entanglements, they look more to the landscape itself, considering how a place is a repository of cultural information and impressions. These projects often emphasise understanding a place through multisensorial, material, and experiential encounters. They may also attend to the immaterial dimensions that generate a “sense of place.”

These mapping processes are informed by artistic methodologies of sensing and investigating place as well as approaches from fields like urban studies, which feature processes of “reading the city” through flâneury (see Figure 4:11); folklore, which examines dynamic relationships between cultural practices, identities, and groups and particular places; and aerial imagery, which has provided new “bird’s eye” perspectives of landscapes.

Mapping processes can be directed to foregrounding ways of seeing, sensing, and making sense of a place while exposing the underlining and often invisible infrastructures and lines of influence that structure the meanings, dynamics, and expressions of a place. In these projects, attention is often paid to the ways in which the aesthetic dimensions of a place can be channelled into the mapping process and the design and presentation of findings.

Figure 4:12 illustrates the three organising schemas presented in this chapter.