Reading Case Law

Lori Bambush

Upon successful completion of this chapter, learners will be able to do the following:

-

Identify the definition and purpose of case law in Canadian legal research.

-

Review the components of case formats, including written, oral, and electronic hearings.

-

Describe the structure and key elements of a case using the FILAC method.

-

Identify the difference between binding and persuasive authority.

-

Recognize the importance of stare decisis in Canadian common law.

-

Outline the key elements of a case: style of cause, facts, issues, law, ratio decidendi, decision, obiter dicta, and disposition.

Introduction

Recall that the primary sources of Canadian law are legislation and case law. Both are integral to successful legal research. This chapter focuses on learning to read case law. In particular, it defines case law and common case law terms, considers the format of a case, and discusses why it is important to learn to read a case. It also demonstrates an effective case-reading technique and gives the reader the opportunity to apply that technique. Learning these skills are vital to conducting proper legal research, as will be shown in this chapter and in the chapters to come.

Defining Case Law

A basic understanding of case law is essential for conducting legal research. Blatt and Kurtz (2020) define case law as “written decisions by judges, adjudicators, masters, or justices of the peace in court and tribunal proceedings” (p. 44). It encompasses cases decided provincially, federally, and internationally, and from all levels of court. A decision or case is a written account by a decision-maker of the facts and the evidence presented, the law applied, the arguments made, the decision rendered—and the reasons for it— in a law case or legal proceeding. Reviewing common terms contained in a case or proceeding will help to make reading case law easier.

Common Legal Terms

Stasiewich (personal communication, March 2024) introduces many common legal terms to students in her Legal Research and Analysis course materials. Several of these terms are explained below.

A legal proceeding may be a motion, a trial, an appeal, or a hearing. A motion is an application by a party to a court or a judge to obtain an order for some kind of relief. A hearing is a formal meeting at which a decision-maker receives evidence, considers the oral arguments of the parties, and makes a decision. An appeal is an application to a higher court to review a judgment to determine whether any errors of law occurred within it, and if so, to have the decision upheld, overturned, or altered. A proceeding may also be identified as either civil or criminal, depending on whether it flows through the civil or the criminal court system.

An administrative proceeding is a written or an oral hearing involving either an individual and/or a company, or individuals or companies and the government, regarding statute-based rights and obligations. A tribunal is an agency that operates like a court to decide disputes between the parties of an administrative proceeding (Nastasi et al., 2020).

Stasiewich (personal communication, March 2024) also differentiates between the titles of the parties in the different types of proceedings. In a motion or a hearing, the applicant is the party that files the application and the respondent is the party that answers or defends the application. In an appeal, the appellant is the party who files the application and the respondent is again the party that answers or defends an appeal. In civil litigation, the plaintiff is the party that initiates the civil action and the defendant is the party that responds to or defends the action. And lastly, in criminal cases, the Crown or Crown Counsel (identified as R for Regina or Rex) is the party that prosecutes the offence and the defendant or the accused is the party that answers or defends the offence. Many of these terms are encountered when reading cases, and the common formats are described next.

Case Formats

The format of a case or decision generally mirrors the format of the proceeding it recounts. There are two primary formats for cases or proceedings: written and oral. In a typical proceeding with a written format, the parties submit evidence to the decision-maker that supports the facts of their case (usually in document form), copies of the law that they deem relevant to their circumstances, and written arguments that set out their case. The parties typically review each other’s information and may cross-examine that information through written and answered queries that are also submitted. The decision-maker then reviews and considers the submitted information, applies the law to the facts, forms a decision, and communicates that decision and the reasons for it in written form to the parties. Motions, applications, and hearings of a less serious nature tend to be implemented in a written format.

Conversely, in a typical proceeding with an oral format, all the parties to the case appear before the judge and are present for its duration. Each party sets forth an opening argument that delineates the essential facts of their case and what they will attempt to prove. Their evidence is submitted to the judge via witness testimony. Each party may cross-examine the other’s witnesses. Then each party, in turn, may re-examine their own witness(es) after cross-examination regarding any new information presented or any required clarification. Relevant law (e.g., legislation and case law) that the parties will rely on is submitted and arguments demonstrating how the law applies to the facts of the case are put forward. The parties then present their final arguments, summarizing the facts of their case, their evidence and relied-upon law, how that law applies to their case, and finally, why the judge should side with them. The judge formulates their decision (and the reasons for it) and may disclose it orally at the proceeding or have it sent to the parties at a later date in written form. This type of format is commonly implemented for trials and more serious applications or hearings. There are some variations of these formats. For example, at an appeal, the appellant and respondent each submit a written summary of the disputed proceeding, along with the facts and relevant law they are relying on for the appeal. No witnesses typically attend to testify, but a transcript of the oral testimony from the earlier proceeding is provided to the judge(s) for review. Each party usually receives the opportunity to present an oral argument before the judge regarding the law for their case. After the judge has examined the provided information, they make a decision of whether to uphold, overturn, alter, retry, or dismiss the case presented for appeal. The reasons for the decision are explained to the parties and written up. It is important to note that appeal judges typically will not consider decisions regarding the facts of the case; however, they may consider those with a perceived mistake of understanding or application of law by a deciding lower court judge.

Another variation is the electronic format, where the hearing occurs via video conference or another method of online visual conference. This type of hearing incorporates elements of both the written and the oral formats to varying degrees, depending on what is required or what will work for the participants at the hearing.

Ideally, in a decision or case, the decision-maker will follow a format conveyed in a research method developed by Maureen F. Fitzgerald (2022, p. 4), called FILAC.

FILAC is an acronym that stands for:

Facts: Analyze the facts.

Issues: Determine the issues.

Law: Find the relevant law.

Analysis: Analyze the law and apply it to the facts.

Communicate: Communicate the results of the research.

When applying FILAC to identify the format or layout of a case, it is important to recognize that the facts are presented, the legal issues are identified, the law is determined, analyzed, and applied to the facts, and then a conclusion or decision is determined. Please note that, in this context, it is the conclusion or decision that is communicated at the end of the process, not the research. Employing this acronym may simplify the process of following a case’s format for some researchers.

Having defined case law, reviewed some common case law vocabulary, and described various formats of cases or decisions, the importance of reading case law is explained in the next section.

The Importance of Case Law

Case law is important as it guides a researcher through the process of determining (and may actually determine) the validity of a client’s case. Blatt and Kurtz (2020) state it can help identify whether the client has a cause of action; if so, what evidence is necessary to prove it; their chances of succeeding at it; and, what relief they may be awarded should they succeed [or penalty should they fail]. Stare decisis, binding, and persuasive authority play an important role in determining the above factors.

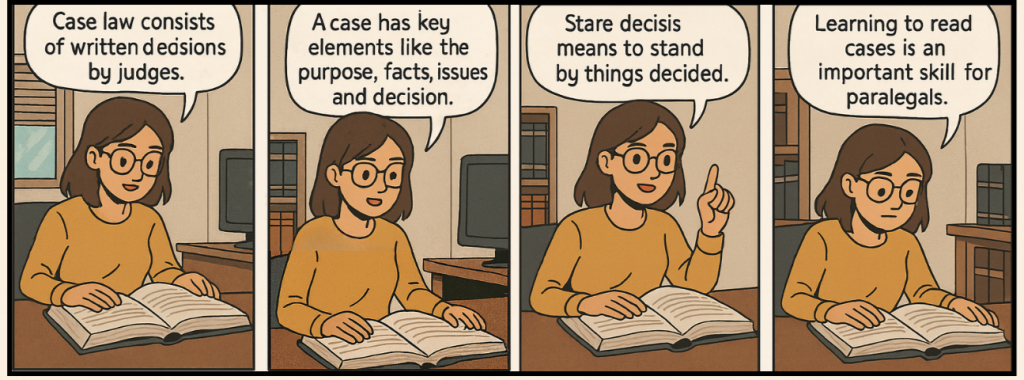

Recall that Canada has a common law legal system (except for Quebec, which has a codified system) where judges must follow the doctrine of stare decisis which means “to stand by things decided” (Blatt & Kurtz, 2020, p. 86). This means that similar cases should be decided in a similar way. The principle requires judges to follow previously made decisions (precedents) with similar facts and legal issues from higher courts within their province or territory and from the Supreme Court of Canada. The precedent cases are said to have vertical binding authority—the courts within that jurisdiction are compelled to follow the higher courts and to decide their cases in a similar manner (University of Toronto, n.d., Primary Sources of Law: Canadian Case Law section). It is important to note that any Supreme Court of Canada decisions, as the highest court in the country, are binding on all other courts in the country. It is also important to note that Canada enforces a concept of horizontal stare decisis that applies to following the previous decisions of the same court in which the current case occurs, although it is not considered binding (Rowe & Katz, 2020). A case may, however, be distinguished from either of these authorities by having facts or legal issues that significantly differentiate it from the precedent. In this circumstance, the precedent (and thereby stare decisis) would likely not apply as the cases would not be sufficiently alike to be considered similar.

Cases may also have persuasive authority. These are decisions with similar legal issues from the same or higher level of court in other provinces or territories (or other jurisdictions) that a court may choose to follow—assuming they do not contradict any relevant binding authority. They, too, may predict and influence how a case is decided if the facts and legal issues are sufficiently similar.

See the diagram below for a brief review of the concepts of stare decisis, as well as binding and persuasive authority.

Both binding and persuasive authority add weight (or value) to the applicability of a researched case—a binding case far more so than a persuasive one. And the higher the court level of the decision, the more powerful or influential the decision. There are, however, other factors that may also contribute to the weight a court would assign a case.

Bueckert et al. (2018) recommend considering all of the following:

- whether the case is binding or persuasive

- the level and jurisdiction of the court

- the similarity of the facts to your case

- the similarity of the legal issues to your case

- the soundness of the reasoning in the case

- whether the court considered pertinent case law in reaching its decision [or whether the case is considered pertinent case law—has it been distinguished, applied, or followed?]

- the age of the case

When choosing case law to support a client’s case, the issues and the facts of the cases should be similar and the case should have at least persuasive authority. Ideally, a researcher wants to find a leading case or one where “a question or problem that is decided in a court of law…is used as an example to decide similar cases” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). The more weight a case has, the more likely the judge in a client’s case will follow that case’s decision-making rationale.

It is important to note that while court decisions are not binding on administrative tribunals, they are persuasive. This means that decisions made at the highest level of court in the relevant jurisdiction (province, territory, or Federal Court system) will have the most impact in the arguments presented on the client’s behalf (CanLII Primer, 2016, pp. 12–13; Daly, 2015, pp. 4–5).

In summary, case law is important both as a method of determining the validity of a client’s case and as a guide for the court’s decision-making process. The more similar the precedent and a client’s case are, the better the precedent will predict the final outcome of the client’s case as well as the court’s rationale for its decision (and the law it applies).

Clearly, understanding and applying case law has a significant impact on any case or proceeding entering or progressing through the legal system. However, in order to understand and apply case law, the researcher must first be able to read it. In the next section, an effective case-reading technique will be discussed and then an opportunity to practice it will be presented.

An Effective Case-Reading Technique

Trying to read through a case—especially a long one—may seem like a daunting task. However, by employing a commonly used case-reading technique, the task may be broken down into manageable steps, systematically worked through, read, and understood. This section will demonstrate how to apply an effective case-reading technique.

Recall that the format of a case mirrors the structure of a proceeding. The decision-maker’s reasoning in a decision also typically mirrors the structure of a court or tribunal proceeding. Therefore, by walking through the steps of the actual proceeding, the researcher may identify and read their way through the key elements of the judgment and the decision-maker’s reasoning.

Style of Cause

A proceeding typically starts with the parties, their representatives or lawyers, and the decision-maker or judge being introduced. This introduction is represented in the style of cause, which is located at the top of the first page of a written case.

The style of cause identifies:

- a citation for the case

- the date the decision was released and/or the date of the hearing

- the court file or action number

- the level of court and its jurisdiction

- the parties involved (and their counsel)

- the name of the judge or the decision-maker (Note that the J after the decision-maker’s name stands for Justice.)

The style of cause is used to locate the case in a printed report and on an online database. These will be discussed in another chapter.

Headnote and Summary

The headnote and summary (when used) are positioned just below the style of cause. These are not always included in a case nor are they considered a part of the proceeding. However, they may still be useful to the researcher. The headnote and summary include catch lines and condensed information about the decision that follows. They are written by the editor of the law reporter or database that publishes the case. The headnote contains words and phrases (catch lines) used to identify key aspects of the case and it may be used as an initial screening device to determine the relevancy or similarity of the case. The catch lines may also be employed as search words for further case law research of similar cases. An example, taken from Weston v. Regan, 2006 ABQB 624, would be as follows:

Family law — Damages for loss of consortium and servitium — Wife seeking damages — General principles

The summary is a brief description of the case. Multiple short summaries may be included, one for each issue in the case.

Please note a warning about headnotes: Blatt and Kurtz (2020) state that they are not always accurate as they are written by an editor and not the decision-maker. Therefore, they should never be relied on in isolation—if the case looks like it might be relevant, read the entire case.

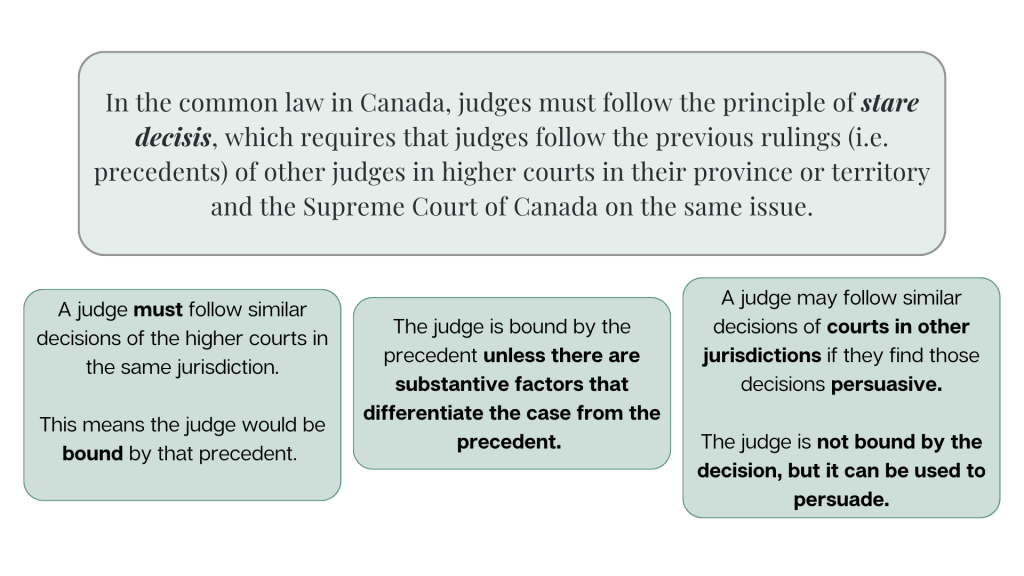

Table of Authorities

The table of authorities is placed just below the headnote and summary (or where they would be if they are absent). This is another element that is sometimes, but not always, included in a case. The table of authorities is a list of the case law and any legislation or secondary sources considered by the decision-maker in making the decision. It is another source of search information for the researcher. See the example below, from Weston v Regan, 2006 ABQB 624:

Purpose

After the introductions have been made, the judge moves into discussing the key elements of the case, beginning with the purpose of the proceeding. The purpose is positioned after the headnote and summary (or directly following the style of cause if they are absent). It is typically the first paragraph of the case. The purpose is the reason or the cause of action for the case before the court. It may be phrased as, “This is a claim for damages arising from…,” “On appeal from the judgment of…,” or it may simply state, “Action for damages for negligence.” It leads into the facts of the case.

Facts

The judge then reviews the facts of the case. The facts are “the who, what, why, when, and how” of the legal scenario presented to the court. In a trial or hearing, they include the parties to the dispute, the events that led up to and created the cause of action, and the evidence submitted to prove each party’s case.

The facts also sometimes include events that occurred after the origin of the cause of action that may affect the decision-maker’s interpretation of the events and the application of law to the events. An example might be mitigating circumstances where a party attempts to reduce the negative impact of the cause of action either for the other party or for themselves.

Also, in an appeal, the decision being appealed is included with the facts.

It is important to pinpoint the relevant facts in a case. An effective way to do this is to identify which are the key issues in the case (discussed next) and then track which case facts the decision-maker has attached to these issues.

Issues

Following a review of the facts, the judge identifies the issues of the case. The issues are the questions that the decision-maker must answer in order to reach a decision. There are two types of issues recognized. The first are factual issues, such as when there is a lack of information required to establish the facts or where the parties do not agree on the stated facts of the case. For example, in a negligence case, the judge may need to determine “whether Balboa was the horse involved in the accident?” This type of question requires a factual answer, not a legal answer. The second type recognized are legal issues and involve legal questions “that arise from the specific facts of a client’s legal problem” (McCarney et al., 2019, pp. 2:9). An example is, having determined that Balboa was the horse involved in the accident, “[w]hether the defendant is liable in negligence either (a) for a breach of duty created by municipal regulations, or (b) for a breach of duty at common law.” Both types of issues must be resolved to decide a case, but the legal issues are the ones to focus on when researching what law is applied to the circumstances of a case.

As the legal issues are what the entire case revolves around, it is imperative to identify them and to understand what they are. Below are some helpful tips for identifying them:

- The decision-maker usually formulates the issues as a subtitle (“Issues”) or as a question (often beginning with the word “whether”).

- After stating the issue, the decision-maker typically follows up with a review of the facts that apply to the issue.

- After stating the issue, the decision-maker usually identifies the law related to the issue, including any factors or tests that need to be met to apply it.

Please note that while some decision-makers disclose the legal issues in a comprehensive list following the facts of a case, others “scatter them throughout their reasons” (Blatt & Kurtz, 2020, p. 47) and the researcher must then search through the text to find them and their related facts. Following the tips outlined above should help ease this process. Conversely, most decision-makers do consistently relay the law applicable to the issues directly after identifying them, and that is what will be discussed next.

Law and Lines of Authority

After identifying the issues that need to be addressed in the proceeding, the decision-maker sets out the existing law for each issue. The authorities relied upon and cited in the proceeding may include legislation (statutes, regulations, and bylaws), case law, and secondary sources such as law journals and textbooks. Both parties typically cite or present their own line of authority, which are “sets of cases that share the same or similar viewpoint over a period of time” (Blatt & Kurtz, 2020, p. 47). These are lists of cases and other sources of law that follow a similar decision-making rationale or set of legal principles over time, and support each party’s position on the issues of the case. The judge often reviews one or two cases or law sources from each party’s line of authority. They then pursue the line of authority that best or most fairly relates to the specific legal issue(s), apply it to the facts of the case, and make a decision. This is called the ratio decidendi and is described next.

Please note that it is important for a researcher to record the line of authority pursued in a relevant or similar case as its cited law becomes a resource list from which further research for their client’s case may be initiated.

Ratio Decidendi and Decision

The ratio decidendi (or ratio) is the “reason for deciding.” It is the most important element in a case for researchers— it is the law that is set out when the case is cited in research. It is a statement that contains both the identified principle of law that the decision-maker uses to decide an issue and the application of that principle to the facts of the case. There should be one written following the discussion of each issue in the case. Therefore, if there are multiple issues discussed in the case, there should also be multiple ratios provided in the case. There should be one that explains the final outcome of the case as well.

Please note that if the proceeding is an appeal and there are dissenting reasons, where not all the judges on the panel agreed with the final decision, this is a minority opinion, and the ratios for these reasons are not relevant for research. In contrast, if there are varying reasons with multiple decision-makers on a panel and most or all of them agree to the decision, this is a majority opinion, and there may be a variety of ratios presented for the same decision, thereby providing the researcher with numerous options for research.

Identifying a ratio may be somewhat difficult. It is helpful to look for phrases such as I am of the view…, I have concluded…, or The court is satisfied that… at the beginning of a sentence or paragraph. Indeed, the ratio often consists of only a single sentence or a short paragraph.

Examples of ratios are: I am satisfied therefore on a balance of probabilities that Mr. Smith was negligent in the operation of his motor vehicle; In my opinion, a threat to invade the bodily integrity or otherwise apply force to the victims is itself a hostile act; and The defendant ought to have known that the plaintiff’s privacy was being so thoroughly invaded as to cause a reasonable man to be worried…I have no hesitation in saying that he is violating the privacy of the person.

While the ratio is the rationale or reason for the decision regarding the issue, the decision is the decision-maker’s final verdict on the issue or case. It is usually located after the ratio, although it may sometimes be written before it. Examples of decisions include: The negligence of one driver is not more than the other; I conclude that the trial judge did not err in convicting the accused of sexual assault upon his victims; and The defendant is liable for the injury. After the ratio and decision are presented, the disposition is declared.

Disposition

At the very end of the proceeding or case, the disposition is announced. The disposition is an order from the court that states the final outcome of the entire proceeding. The disposition provides the researcher with potential outcomes for their client’s case. How successful or unsuccessful are they likely to be? Examples include: This action is dismissed; The appeal is allowed and the judgment of the trial is set aside; and I fix damages at $1,000. The disposition may also discuss further administrative procedures that should occur, such as how and when to make submissions on costs.

Obiter Dicta

A final element (while not a key element) to be discussed in reading a case, is obiter dicta (or obiter) meaning “words by the way” (Blatt & Kurtz, 2020, p. 48). This is information that a decision-maker includes in the written judgment that is not directly related to the decision. The decision-maker might voice an opinion about a situation, provide a definition that clarifies a factual issue, or tell an anecdote that will not have any bearing on the decision. It is “commentary in a judicial decision that does not constitute a legal principle but that may provide a useful context for the decision” (McCarney et al., 2019. P. C:5). This information is generally not useful to the researcher.

Case-Reading Technique Summary

To summarize the case-reading technique, the researcher needs to identify each of the key elements in the case, in particular: the purpose, the facts, the legal issues, the law, the ratio decidendi, the decision, and the disposition. Recall that the FILAC research method used to describe case format near the beginning of the chapter also contains most of these elements. Applying that acronym may also be a good reminder of what to look out for when reading a case. And remember, if the researcher walks their way through a typical legal proceeding, they should be able to identify the various elements in the case.

Being able to read a case is critical to legal analysis as well as to locating other relevant cases. It requires some skill but most cases follow a similar format, and after reading numerous cases, the researcher should become adept at identifying the important information in a case.

Summary

Learning how to read case law is an essential skill for legal researchers. Case law refers to written decisions that are made by court and tribunal decision-makers. Researching case law helps to determine whether the client has a case, what evidence needs to be provided to prove the case, and what the odds are of winning their case. It helps the researcher to identify precedents with binding or persuasive authority, and to anticipate the weight a judge might assign to a cited case. Reading case law also provides potential relevant lines of authority and the cases (and legislation) that may be used to find other relevant case law (and legislation) to support the client’s case.

The format of a case typically mirrors that of the proceeding itself and can thereby simplify locating important information in the written decision. Applying an effective case-reading technique further clarifies the process of identifying the key elements of a case—which are the purpose, the facts, the issues, the law, the ratio decidendi, the decision, and the disposition. The more a researcher practices this technique, the more efficient and adept they will become at it.

Researching case law can be time-consuming, and sometimes frustrating, but putting in the work to find the best case law for your client’s issue(s) is worth the effort. Competently reading case law helps ensure that the most similar, relevant, and applicable case law authority is employed in supporting a client’s case and helping their case succeed. Learning to use case citations to identify and search for case law in printed and online law reporters and databases is also key to this endeavour and will be discussed in the next chapter.

Activity: Reading a Case – R v Brown

Read through the following case, R. v Brown, 2016 ABPC 110, and practice identifying the key case elements and important case information. Please note that this case is one where the issues are scattered throughout the text, so the reader may have to search for some of them. Also, it is probably easiest to copy the text to a Word document and work from that.

State the paragraph numbers where the case elements listed below are found.

- the purpose

- the facts

- the issues

- the law

- the ratio decidendi for each issue and for the case

- the decision for each issue and for the case

- the disposition

Next, highlight (or otherwise identify), within the paragraphs specified above, the specific text that states each of the elements listed above.

Finally, summarize (but do not paraphrase) the highlighted sections that directly relate to:

- the facts

- the issues

- the law

Compare your work to the answers in the drop-down menu below.

Answers to Reading a Case – R v Brown

- State the paragraph numbers where the following case elements are found:

- the purpose: para. 1

- the facts: paras. 2-5

- the issues: paras. 6, 19-20, and 19 and 25

- the law: paras. 9-16, 19-23, and 26-3

- the ratio decidendi for each issue identified: paras. 17, 24, and 33

- the decision for each issue identified: paras. 18, 24-25, and 34

- the disposition: para. 34

- Highlight (or otherwise identify), within the paragraphs specified above, the text that states each of the elements listed above:

- The Purpose

- The defendant is charged with performing or engaging in a stunt on a highway in contravention of section 115(2)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act, R.S.A.2000, c. T-6. (para. 1)

- The Facts

- Park Warden Lucas Habib gave evidence that on July 20, 2015, he saw the defendant and four others longboarding down a steep hill on Highway 93A in Jasper National Park. They had a vehicle behind them with its hazard lights on. There was no vehicle in front of them. The Warden gave evidence that he observed a few vehicles that had pulled over as the longboarders had gone by. (para. 2)

- Warden Habib pulled the group over at the bottom of the hill and issued a ticket to the defendant for stunting. He gave evidence that no permit is available for this activity. (para. 3)

- The defendant gave evidence which I accept. He is an experienced skateboarder having more than eight years’ experience. The only place available to train is down a paved hill. He was wearing protective equipment. He travelled in the correct lane, did not exceed the speed limit and was able to slow down and stop upon request. (para.4)

- The defendant acknowledged he had been warned not to longboard in Jasper National Park, but gave evidence that he did not believe that he was distracting, startling or interfering with other users of the highway. (para. 5)

- The Issues

- Issue 1

- I …[need] to determine if longboarding in the manner that he did is illegal in Jasper National Park. (para. 6)

- Issue 2

- However, the matter does not stop here as the accused was charged under section 115(2)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act. Section 115(2)(e) states:

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- (e) perform or engage in any stunt … (para.19)

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- [T]he question as to what constitutes stunting…(para. 20)

- However, the matter does not stop here as the accused was charged under section 115(2)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act. Section 115(2)(e) states:

- Issue 3

- Section 115(2)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act. Section 115(2)(e) states:

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- (e) perform or engage in any…other activity that is likely to distract, startle or interfere with users of the highway. (para. 19)

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- I must next consider whether the defendant’s engagement in the activity of longboarding constitutes an “other activity” that is likely to distract, startle or interfere with users of the highway. (para. 25)

- Section 115(2)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act. Section 115(2)(e) states:

- Issue 1

- The Law

- For Issue 1

- The Crown produced no evidence that there is any regulation that prohibits longboarding in Jasper National Park. (para. 9)

- The Canada National Parks Act, S.C. 2000, c. 32 provides that Canada’s National Parks are dedicated to the public. Section 4(1) states:

- The national parks of Canada are hereby dedicated to the people of Canada for their benefit, education, and enjoyment, subject to this Act and the regulations, and the parks shall be maintained and made use of so as to leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations. (para. 10)

- Section 47(2) of the National Parks Highway Traffic Regulations, C.R.C., c. 1126 states:

- No person shall skate, roller skate, roller blade, roller ski or ride a skateboard on any highway or sidewalk in a town, visitor centre, or resort subdivision. (para. 11)

- A “highway” is defined in section 2 of the Regulations as including “a road, street, avenue, parkway, driveway, lane, square, bridge, viaduct, trestle or other place within a park intended for use by the public for the passage or parking of vehicles.” (para. 12)

- While a longboard is not specifically listed in section 47(2) it is similar to a skateboard. (para. 13)

- Section 47(3) of the Regulations provides:

- Every person who roller blades or roller skis on a highway outside a town, visitor centre or resort subdivision shall travel as close as possible to the left-hand edge or curb of the highway and, when roller blading or roller skiing with other persons, shall travel in single file. (para. 14)

- Skateboarding is not referred to in section 47(3) of the Regulations. (para. 15)

- I have found no other provision in any other Regulations made under the Canada National Parks Act which specifically prohibits a person from skateboarding or longboarding in a National Park. (para. 16)

- For Issue 2

- Traffic Safety Act, Section 115(2)(e) states:

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- (e) perform or engage in any stunt or other activity that is likely to distract, startle or interfere with users of the highway. (para. 19)

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- The word “stunt” is not defined in section 1(1) or elsewhere in the Traffic Safety Act. It is also not defined in Alberta’s Interpretation Act, RSA 2000, c. I-8. The question as to what constitutes stunting has been considered by courts in Alberta and Saskatchewan. (para. 20)

- In R. v. Tremblay (1974), 1974 CanLII 1138 (AB CA) at para. 10, [1975] 3 W.W.R. 589 (Alta. C.A.), the Alberta Court of Appeal relied on the definition of the word “stunt” set out in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd revised edition:

- An “event” in an athletic competition or display; a feat undertaken as a defiance in response to a challenge; an act which is striking for the skill, strength, or the like, required to do it; a feat, something performed as an item in an entertainment.

- In recent use, an enterprise set on foot with the object of gaining reputation or signal advantage. In soldiers’ use often vaguely: An attack or advance, a “push,” “move.”

- In wider use, an enterprise, performance. Hence Stunt: to perform stunts; spec. of a motorist, an airman, etc., to perform spectacular and daring feats. Stunter, Stuntist. (para. 21)

- The Alberta Court of Appeal relied upon this definition of “stunt” in R. v Jones, 1983 ABCA 70 (CanLII), [1983] 4 W.W.R. 144 (Alta. C.A.). So did Justice of the Peace McIlhargey in R. v James (2004), 4 M.V.R. (5th) 231 (Alta. Prov. Ct.) and Justice Moore in R. v Burton (1984), 29 M.V.R. 229 (Sask. Q.B.). (para. 22)

- The Canadian Oxford Dictionary, 2nd edition, defines “stunt” as follows:

- (1) Something unusual done to attract attention;

- (2) An act notable or impressive on account of the skill, strength, or daring, etc., required to perform it; an exciting or dangerous trick or manoeuvre. (para. 23)

- Traffic Safety Act, Section 115(2)(e) states:

- For Issue 3

- Traffic Safety Act, Section 115(2)(e) states:

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- (e) perform or engage in any … other activity that is likely to distract, startle or interfere with users of the highway. (para. 19)

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- McIlhargey in James (para. 14) in my opinion does a particularly good analysis of the law in this regard and I adopt his analysis. McIlhargey in James, concludes: “It is clear that the subject of concern in section 115(2)(e) is not the conduct itself but the effect of that conduct on users of the highway.” (para. 26)

- In Jones (paras. 12 and 14), the Alberta Court of Appeal considered the meaning of “startle,” “distract,” and “interfere” in what was then section 104(1) of the Highway Traffic Act, R.S.A. 1975(2), c. 56. Prowse J.A. explained the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, revised 3rd ed. (1973), defines “startle” as follows: “to cause to start; to frighten; to surprise greatly; to shock”. “Distract” is defined as “turning aside in a different direction; to perplex or to confuse; to derange the intellect”. The word “interfere” means “to run into each other; to intersect; to interpose so as to affect some action; to intervene.” (para. 27)

- Justice Prowse (Jones, para. 15) held:

- the ordinary meaning of these words leads me to conclude that the legislation was not directed at activities that merely drew attention to oneself or excited towards oneself pleasurable emotions of those whose attention is drawn to them. A distraction must be more serious than an attraction. If such were not the case, one could envision everyday activities which would fall within this section, in fear that those activities might divert the attention of some careless drivers. (para. 28)

- McIlhargey J. P. in James expressed at paragraph 18:

- I am satisfied that section 115(2)(e) is directed at conduct occurring on or near a highway that adversely impacts the exercise by a driver of the due care and attention that is required for the safe operation of a vehicle on the highway. The conduct complained of must be of a compelling nature, such that the effect or consequence of that conduct on the users of the highway is or is likely to be serious and significant. (para. 29)

- After considering the decision in Tremblay, Justice Currie in R. v Beaudoin, 2009 SKQB 113, at para. 18, opined the use of the phrase:

- “that is likely to” indicates that the legislature intended to entirely prohibit this kind of activity on highways, regardless of whether in a particular case the activity had affected another driver, and regardless of whether in a particular case it could be established that another driver was nearby. (para. 30)

- According to Justice Currie (para. 19):

- The focus of s. 214(2) [of Saskatchewan’s The Traffic Safety Act] is on the driving activity that has the potential to create a hazard on a highway, not on whether a hazard actually has been created by the driving activity on any one occasion. This focus is consistent with the overall purpose of the statute, which is to ensure traffic safety. (para. 31)

- The wording of section 214(2) of Saskatchewan’s Traffic Safety Act mirrors that of section 115(2) of Alberta’s Act, with the exception that section 214(2) applies specifically to a “driver.” (para. 32)

- Traffic Safety Act, Section 115(2)(e) states:

- For Issue 1

- The Ratio Decidendi for Each Issue Identified

- For Issue 1

- The manner in which the defendant engaged in the longboarding does not appear to constitute “prohibited conduct” as defined in section 32(1) of the National Parks General Regulations, SOR/78-213. No evidence was submitted during the trial indicating whether the Superintendent has designated longboarding as a prohibited activity under section 7(1) of the General Regulations. As indicated above, the Park Warden did give evidence that no permit is available authorizing a person to longboard in Jasper National Park. (para. 17)

- For Issue 2

- The defendant’s actions in longboarding down a steep hill, along a highway in Jasper National Park, in the manner that he did, in my opinion, does not constitute “stunting” within the meaning of section 115(2)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act. The evidence establishes that he and his companions were travelling in a careful and prudent manner. There is no evidence that they were racing or performing tricks or doing anything unusual to attract attention. (para. 24)

- For Issue 3

- McIlhargey in James {at para. 14}in my opinion does a particularly good analysis of the law in this regard and I adopt his analysis. McIlhargey in James, concludes: “It is clear that the subject of concern in section 115(2)(e) is not the conduct itself but the effect of that conduct on users of the highway.” (para. 26)

- After giving consideration to the reasoning of Justice Currie in Beaudoin, the Crown has not satisfied me beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused’s engagement in longboarding, in the manner that he did, was so compelling that it had or was likely to have a serious and significant effect on other users of the 93A Highway. (para. 33)

- For Issue 1

- The Decision for Each Issue Identified

- For Issue 1

- …Unless a person is longboarding on a highway or sidewalk “in a town, visitor centre or resort subdivision” longboarding is not in and of itself illegal in Jasper National Park. (para. 18)

- For Issue 2

- I find the defendant did not commit the offence of stunting. (para. 34)

- For Issue 3

- The evidence establishes that he and his companions were travelling in a careful and prudent manner. There is no evidence that they were racing or performing tricks or doing anything unusual to attract attention. (para. 24)

- For Issue 1

- The Decision for the Case

- The Crown has failed to establish its case. (para. 34)

- The Disposition

- I acquit the defendant. (para. 34)

- The Purpose

- Summarize (but do not paraphrase) the highlighted sections that directly relate to:

- The Facts

- Park Warden Lucas Habib gave evidence that on July 20, 2015, he saw the defendant and four others longboarding down a steep hill on Highway 93A in Jasper National Park. They had a vehicle behind them with its hazard lights on. There was no vehicle in front of them. (para. 2)

- Warden Habib pulled the group over at the bottom of the hill and issued a ticket to the defendant for stunting. He gave evidence that no permit is available for this activity. (para. 3)

- [The defendant] is an experienced skateboarder having more than eight years’ experience. The only place available to train is down a paved hill. He was wearing protective equipment. He travelled in the correct lane, did not exceed the speed limit and was able to slow down and stop upon request. (para. 4)

- The defendant acknowledged he had been warned not to longboard in Jasper National Park, but…he did not believe that he was distracting, startling or interfering with other users of the highway. (para. 5)

- The Issues

- …[I]f longboarding in the manner that he did is illegal in Jasper National Park. (para. 6)

- A person shall not do any of the following:…perform or engage in any stunt…that is likely to distract, startle or interfere with users of the highway. (para. 19) The question as to what constitutes stunting… (para. 20)

- …Whether the defendant’s engagement in…longboarding constitutes an “other activity” that is likely to distract, startle or interfere with users of the highway. (para. 25)

- The Law

- Section 47(2) of the National Parks Highway Traffic Regulations, C.R.C., c. 1126 states:

- No person shall skate, roller skate, roller blade, roller ski or ride a skateboard on any highway or sidewalk in a town, visitor centre or resort subdivision. (para. 11)

- A “highway” is defined in section 2 of the Regulations as…“a road, street, avenue, parkway, driveway, lane, square, bridge, viaduct, trestle or other place within a park intended for use by the public for the passage or parking of vehicles.” (para. 12)

- “[P]rohibited conduct” as defined in section 32(1) of the National Parks General Regulations, SOR/78-213. (para. 17) [Which, when looked up, states the following:

- 32 (1) No person shall, in a Park,

- (a) cause any excessive noise;

- (b) conduct or behave in a manner that unreasonably disturbs other persons in the Park or unreasonably interferes with their enjoyment of the Park; or

- (c) carry out any action that unreasonably interferes with fauna or the natural beauty of the Park.]

- 32 (1) No person shall, in a Park,

- Section 7(1) of the General Regulations [when looked up, states the following regarding “Prohibited Activities”:

- 7 (1) The superintendent may, where it is necessary for the proper management of the Park to do so, designate certain activities, uses or entry and travel in areas in a Park as restricted or prohibited.] (para.17)

- Section 115(2)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act…states:

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- (e) perform or engage in any stunt or other activity that is likely to distract, startle or interfere with users of the highway. (para. 19)

- A person shall not do any of the following:

- The word “stunt” is not defined in section 1(1) or elsewhere in the Traffic Safety Act. (para. 20)

- It is also not defined in Alberta’s Interpretation Act, RSA 2000, c. I-8. (para. 20)

- R v Tremblay (1974), 1974 CanLII 1138 (AB CA) at para. 10:

- the Alberta Court of Appeal relied on the definition of the word “stunt” set out in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd revised edition:

- An “event” in an athletic competition or display; a feat undertaken as a defiance in response to a challenge; an act which is striking for the skill, strength, or the like, required to do it; a feat, something performed as an item in an entertainment.

- In recent use, an enterprise set on foot with the object of gaining reputation or signal advantage. In soldiers’ use often vaguely: An attack or advance, a “push,” “move.”

- In wider use, an enterprise, performance. Hence Stunt: to perform stunts; spec. of a motorist, an airman, etc., to perform spectacular and daring feats. Stunter, Stuntist. (para, 21)

- the Alberta Court of Appeal relied on the definition of the word “stunt” set out in the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 3rd revised edition:

- R v James (2004), 4 M.V.R. (5th) 231 (Alta. Prov. Ct.) at para 14:

- “It is clear that the subject of concern in section 115(2)(e) is not the conduct itself but the effect of that conduct on users of the highway.” (para. 26)

- R v Beaudoin 2009 SKQB 113 at para. 18:

- [regarding section 1152)(e) of the Traffic Safety Act]: “that is likely to” indicates that the legislature intended to entirely prohibit this kind of activity on highways, regardless of whether in a particular case the activity had affected another driver, and regardless of whether in a particular case it could be established that another driver was nearby. (para. 30)

- R v Beaudoin 2009 SKQB 113 at para 19:

- The focus of s. 214(2) [of Saskatchewan’s The Traffic Safety Act] is on the driving activity that has the potential to create a hazard on a highway, not on whether a hazard actually has been created by the driving activity on any one occasion. This focus is consistent with the overall purpose of the statute, which is to ensure traffic safety. (para. 31)

- [S]ection 214(2) of Saskatchewan’s Traffic Safety Act mirrors that of section 115(2) of Alberta’s Act, with the exception that section 214(2) applies specifically to a “driver.” (para. 32)

- Section 47(2) of the National Parks Highway Traffic Regulations, C.R.C., c. 1126 states:

- The Facts

Reflection Questions

-

When reading a case, which part do you find most difficult to identify and why? How might practicing with more case readings help improve this?

-

Think about the concept of precedent. How would identifying whether a case is binding or persuasive affect your ability to support your supervising lawyer’s legal argument?

-

Imagine you are researching a case for a client who is self-represented. How would you explain the relevance of reading and understanding case law in plain language?

References

Blatt, A., & Kurtz, J. (2020). Legal research: Step by step (5th ed.). Emond Publishing.

Bueckert, M. R., Clair, A., Cote, M., Khan, Y., & Ostick, M. (2018). The Canadian legal research and writing guide. Canadian Legal Information Institute. https://www.canlii.org/en/commentary/doc/2018CanLIIDocs161#!fragment//BQCwhgziBcwMYgK4DsDWszIQewE4BUBTADwBdoByCgSgBpltTCIBFRQ3AT0otokLC4EbDtyp8BQkAGU8pAELcASgFEAMioBqAQQByAYRW1SYAEbRS2ONWpA

Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Leading case. In Dictionary-Cambridge.org. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/leading-case

Daly, P. (2015). The principle of stare decisis in Canadian administrative law (2015 CanLIIDocs 325). CanLII. https://canlii.ca/t/287c

Fitzgerald, M. (2022, July). Legal problem solving: Reasoning, research and writing (8th ed.). LexisNexis.

McCarney, M., Kuras, R., & Demers, A. (with Kierstead, S.). (2019). The comprehensive guide to legal research, writing and analysis (3rd ed.). Emond Publishing.

Nastasi, L., Pressman, D., & Swaigen, J. (2020). Administrative law: Principles and advocacy (4th ed.). Emond Publishing.

National Self-Represented Litigants Project. (2016). The CanLII Primer: Legal research principles and CanLII navigation for self-represented litigants (2016 CanLIIDocs 235). https://canlii.ca/t/27tb.

R. v Brown, 2016 ABPC 1. https://canlii.ca/t/gmvfh

Rowe, M. J., & Katz, L. (2020). A practical guide to stare decisis. Windsor Review of Legal and Social Issues, 41, 1–27. https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=analytical-materials&id=urn%3acontentItem%3a605H-X981-JFSV-G03C-00000-00&context=1519360&identityprofileid=FV7WGS58424

University of Toronto. (n.d.). Legal research for the public researcher. Henry N.R. Jackman Faculty of Law Library. https://library.law.utoronto.ca/step-2-primary-sources-law-canadian-case-law-0

Weston v Regan, 2006 ABQB 624. https://canlii.ca/t/1p5l7

The ratio decidendi (or ratio) is the “reason for deciding.” It is the most important element in a case for researchers – it is the law that is set out when the case is cited in research.