Chapter 1: What is Sustainability

Tai Munro

Key Ideas

In this chapter, you will learn about:

- the beginnings of the modern sustainability movement

- the different models and definitions of sustainability

The Modern Sustainability Movement

While Hans Carl von Carlowitz is documented as introducing sustainability ideas in the eighteenth century (Seefried, 2015), there was little discussion of sustainability prior to the 1970s (Caradonna, 2018; Seefried, 2015). However, as the sustainability movement “would not have come into existence” without the environmental movement (Johnson & Greenberg, 2018, p. 138), it is relevant to discuss the environmental movement prior to the 1970s.

The environmental movement in the late 1800s to early 1900s largely fell into two main approaches: conservationism, which focused on protecting pristine nature for human recreational use, and preservationism, which protected untouched nature. Both shared a complete ignorance of the legacy of Indigenous Peoples while applying Western values, including the separation of humans from nature, the dominance of humans over nature, and that all problems could be solved in the future (Johnson & Greenberg, 2018). These approaches were maintained until after the world wars.

In the decades following World War II, a number of developments set the stage for “the explicit formulation of the sustainability movement, which took shape in the 1980s and 1990s” (Caradonna, 2018, p. 10). These developments included growing awareness of ecology and the risks of nuclear energy, environmental pollutants, and hazardous wastes (Johnson & Greenberg, 2018); the work of economists like E.F. Schumacher and Herman Daly, who argued that economies had to recognize that nature is finite (Caradonna, 2018; Schumacher, 1973); the emergence of systems theory, primarily from the Club of Rome (Caradonna, 2018; Seefried, 2015); and the work of people like Rachel Carson, who was foundational in connecting environmental damage to the lives of everyday people (Caradonna, 2018; Johnson & Greenberg, 2018; Seefried, 2015).

employee photo

Public Domain. Circa 1940

Rachel Carson was a biologist and advocate for the environment. One of her most commonly known works is Silent Spring, published in 1962. Carson wrote the book after seeing widespread harm due to the use of pesticides. Carson and Silent Spring were catalysts for the environmental movement at the time. In addition, she stands out as one of the few voices at that time that was not a white male. While some of the issues have changed, reading Silent Spring also points out how much the system has not changed. Carson talks about the speed of changes created by humans (Carson, 1962). This speed, which we are witnessing today with disasters like climate change, is too fast for nature to adapt to and thus is causing widespread issues.

Another event that shaped the movement around this time was a photograph called Earthrise (Johnson & Greenberg, 2018; Seefried, 2015). Astronaut William Anders took Earthrise as he

orbited the moon on Apollo 8. This was the first real photograph that pictured the Earth against the inky blackness of space. It dissolved arbitrary borders and showed the precariousness of life on Earth. As Anders said 30 years later, “All of humanity appeared joined together on this glorious-but-fragile sphere” (2018, para. 7).

There were indications that humans would become more environmentally friendly following these events and others. Concerns about humans running out of oil fueled these efforts during the 1970s. However, new sources of oil were found, and the myth of abundance grew again (Seefried, 2015).

While not directly connected to the environmental movement, there were several social justice movements over this same time period, including the civil rights movement, women’s liberation, and the student movement. These movements contributed to the development of sustainability, which, unlike the environmental movement, was interested in “balancing social issues, environmental concerns, and economics” (Caradonna, 2018, p. 12).

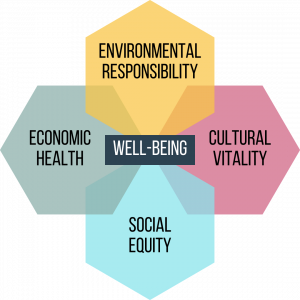

Jump ahead to the late 1980s, and we see the publication of the Brundtland Report “Our Common Future.” This document provided a definition of sustainable development that mentioned keeping future generations in mind and meeting needs. Since then, many definitions and models have bounced around the field. They attempt to identify the different areas of concern that need to be considered to achieve sustainability, generally centering on the environment, economy, society, and, most recently, culture. Despite the presence of these other areas within the definitions and models, the environment is still the most common focus.

Before we continue, it is important to recognize that the history of sustainability documented here and within the emerging field of history of sustainability “has been based on printed sources written by social, intellectual, and political elites in Europe and North America” (Caradonna, 2018, p. 13). Thus, while we have traced the emergence of the concept in Western society, we are missing many voices from this discourse.

Sustainability Definitions and Models

Caradonna (2018) has synthesized the history of defining sustainability and has found four main ideas:

- “Human society, the economy, and the natural environment are necessarily interconnected” (p. 12).

- In order to persist over long periods of time, human societies need to stay within ecological limits.

- Human society needs to engage in “future-oriented planning” (p. 12).

- Small and local needs to be prioritized over big and centralized in order to exist long term.

While Caradonna (2018) argues that these are key ideas within sustainability definitions, they do not necessarily all appear within our common or popular definitions or models of sustainability.

Reflection 1.1: Definitions and Models

Take some time with each definition and model that follows, and ask yourself:

- What ideas are the most prominent?

- What is your initial reaction?

- What does it imply about the relationship between or the importance of different components of sustainability?

- Are there opportunities for different people to interpret it differently? If so, is this positive, negative, or neutral?

The definitions and models have been selected to provide a range of examples of how sustainability may be understood and to examine how they may compare and contrast with each other; for each one we chose, there are others we did not include.

Definitions

Models

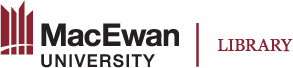

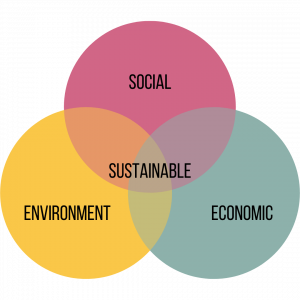

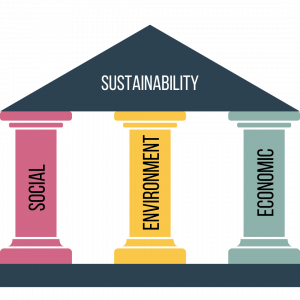

Models are another way of communicating what is included within sustainability. There are a number of common models of sustainability. Unfortunately, the models are used so ubiquitously that it is generally difficult to determine their first use and, therefore, difficult to credit the original sources for each.

Another prominent model within the field of business is the triple bottom line of people, profit, and planet. This model is similar to the first model shown here but changes the labels on the circle. It is a good example of how, with so many different stakeholders, sustainability will likely always be subject to discussion and debate. This can make working together towards a common goal challenging for people. It also means that even when we use the same language, we may understand it differently. As a result, we can completely miss that we might have a basic difference in understanding until it is too late, unless we take time to clarify what we all mean. On the other hand, Ramsey (2015) argues that having a clear definition of sustainability will not actually clarify the issue of sustainability. To clarify sustainability, we need to look at the actions we do; how is sustainability performed?

Activity 1.1: What is Sustainability Discussion

Based on your prior understanding of sustainability and the history and definitions that you have been introduced to in this chapter, answer the following:

- Were you surprised by this history or by any of the definitions and models of sustainability? In what way was it surprising or not?

- Are there one or more definitions and models that appeal to you and why?

- Are there any definitions or models that you disagree with and why?

References

Anders, B. (2018, December 24). 50 years after ‘Earthrise,’ a Christmas eve message from its photographer. Space.Com. https://www.space.com/42848-earthrise-photo-apollo-8-legacy-bill-anders.html

Brundtland, G. H. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf

Caradonna, J. L. (2014). Sustainability: A History. Oxford University Press.

Caradonna, J. L. (2018). Sustainability: A new historiography. In J. L. Caradonna (Ed.), Routledge handbook of the history of sustainability (pp. 9-25). Routledge.

Carson, R. (1962). Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin.

Johnson, E. W. & Greenberg, P. (2018). The US environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s: Building frameworks of sustainability. In J. L. Caradonna (Ed.), Routledge handbook of the history of sustainability (pp. 137-150). Routledge.

Ramsey, J. L. (2015). On Not Defining Sustainability. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 28(6), 1075–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-015-9578-3

Reductionism. (2020). In The Encyclopaedia Britannica. The Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/reductionism

Schumacher, E. F. (1973). Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Blond & Briggs.

Seefried, E. (2015). Rethinking progress. On the origin of the modern sustainability discourse, 1970-2000. Journal of Modern European History 13(3), 377-400. https://doi.org/10.17104/1611-8944-2015-3-377

Sustainability, n. (2022). In OED Online. Oxford English Dictionary. https://www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/299890?print

University of British Columbia. (2014). 20-Year Sustainability Strategy For the University of British Columbia, Vancouver Campus. University of British Columbia. https://sustain.ubc.ca/sites/sustain.ubc.ca/files/uploads/CampusSustainability/CS_PDFs/PlansReports/Plans/20-Year-Sustainability-Strategy-UBC.pdf