Chapter 10: Ethnography

Ethnographic knowledge emerges not through detached observation but through conversations and exchanges of many kinds among people interacting in diverse zones of entanglement.

— Danielle Elliott & Dara Culhane, 2017, p. 3

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

- Define ethnography and describe the role of an ethnographer.

- Outline the main features of ethnographic studies.

- Differentiate between the four main roles of ethnographers engaged in fieldwork.

- Describe the main stages of fieldwork.

- Explain the techniques used by ethnographers in order to blend into a group.

- Discuss ethical issues in fieldwork.

INTRODUCTION

Ethnographers “are social scientists who undertake research and writing about groups of people by systematically observing and participating (to a greater or lesser degree) in the lives of the people they study” (Madden, 2023, p. 1). The historical origins of ethnography can be traced to naturalistic observation and fieldwork in social and cultural anthropology, and later in the Chicago school of sociology (O’Reilly, 2009). Ethnographers share the assumption that to understand a group, one must engage in fieldwork that involves spending a considerable length of time with the group in its natural setting. This fieldwork includes watching, listening, taking notes, asking questions, and even perhaps directly participating in the activities and conversations as a member of the group being studied. While ethnography is often used interchangeably with the term participant observation, ethnography is probably better understood as a multimethod approach to field research that may include any number of qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques undertaken to understand a social group or culture in its natural setting. Data collection in naturalistic settings can be accomplished using systematic observation, participant observation, in-depth interviewing, field notes, surveys, and even visual materials such as drawings and photographs. It is sometimes debated whether ethnography should even be considered a methodology in and of itself since the purpose of ethnography is intricately tied to the product of fieldwork: the description of a group, culture, or process. From this perspective, “ethnography is about telling a credible, rigorous, and authentic story” (Fetterman, 2019, p. 1). Most importantly, as implied by the opening quote, the knowledge gleaned through ethnography is based on “collaborative” modes of inquiry (Elliot & Culhane, 2017).

William Foote Whyte’s (1943) Street Corner Society

As a pioneer in ethnography, William Foote Whyte spent three and a half years in an inner-city Italian district in Boston’s North End, dubbed Cornerville, living among, interacting with, and studying various groups, including a gang he refers to as the “corner boys” (Whyte, 1943). In a later book called Participant Observer: An Autobiography (1994), Whyte describes how he learned to conduct ethnographic research for his “slum study” through trial and error, beginning with an overly ambitious research topic in which he first hoped to study

the history of the North End, the economics (living standards, housing, marketing, distribution, and employment), the politics (the structure of the political organization and its relations to the rackets and the police), the patterns of education and recreation, the church, public health, and—of all things—social attitudes. (p. 64)

Following the advice of his mentors, including L. J. Henderson and Talcott Parsons, Whyte narrowed his “ten-man” project into something more manageable for one person lacking in field experience, and then set out to gather information from residents.

As a researcher, Whyte encountered several false starts, beginning with knocking on doors in hopes of surveying tenants about their living conditions. As he surmised, “it would have been hard to devise a more inappropriate way to begin the study I eventually made. I felt ill at ease and so did the people. I wound up the study of the block and wrote it off as a total loss” (pp. 65–66). Next, Whyte tried out a method shared by an economics instructor who claimed it was easy to learn about local women whilst purchasing drinks for them in a bar. This approach proved even worse for Whyte, who was nearly thrown out of a bar that he later learned was never frequented by any North Enders anyway (Whyte, 1994). It was only after Whyte met Ernest Pecci (whom he called Doc) that he understood the fundamental importance of getting to know someone from the community. Among many other insights, Whyte’s (1943) early work teaches us that to study a group of interest, a researcher must first find a way to access that group. Knowing someone who is already a member of the group can be extremely helpful in this regard. In addition, the insider can also be of assistance in explaining what is going on and how to conduct oneself within that group to be accepted, to not stand out, and to not offend anyone. Finally, it is often through the establishment of relationships developed while in the field that a researcher begins to gain an insider perspective needed to better understand events from the perspective of those experiencing them.

MAIN FEATURES OF ETHNOGRAPHY

To help you understand what ethnography is and how it is distinct from other research methods used by social scientists, this section describes 10 main features of ethnographic studies, adapted from anthropologist Harry Wolcott’s (2010, pp. 90–96) list of what he considers the “essence” of ethnography after more than 50 years of experience in the field.

- Ethnography takes place in natural settings.

- Ethnography is context-based.

- Ethnography relies on participant observation.

- Ethnography is undertaken by a single principal investigator.

- Ethnography involves long-term acquaintances.

- Ethnography is non-judgmental.

- Ethnography is reflexive.

- Ethnography is mostly descriptive.

- Ethnography is case-specific.

- Ethnography requires multiple techniques and data sources.

Ethnography Takes Place in Natural Settings

As an example of how ethnography takes place in natural settings, Olding et al. (2023) spent 20 months carrying out 100 hours of observation, three-site specific focus groups, and several interviews at overdose prevention sites in British Columbia to learn more about the role of “overdose prevention site responders.” Findings showed that overdose prevention site responders tended to be community members with highly proficient experiential knowledge and expertise based on frequent practice (e.g., in administering naloxone) as well as a broader understanding of drug use and the culture surrounding it (i.e., they were instrumental in providing support and protection to drug users against stigmatization) (Olding et al., 2023).

The internet has changed the way we view natural settings and communities, and the way ethnographers do research. People can be members of all sorts of virtual communities, from friends and followers on social networking sites such as Facebook and Instagram, to various online support groups, to virtual worlds that are part of interactive games. Virtual ethnography is the term for “the in-depth study of a group or culture that exists in an online environment” (van den Hoonaard & van den Scott, 2022, p. 99). In this case, ethnographic research is undertaken through participation on the internet with other group members as part of a virtual community, such as a discussion group.

Ethnography is Context-Based

To understand social interactions and social processes, an ethnographer also considers the wider context in which the studied phenomenon arises. The context often contains important conditions that help frame problems and can provide clues to why events unfold the way they do. For example, in an evaluation of an educational program, Fetterman (1987) noted that low school attendance should be interpreted within the environment in which the students and their program were situated. In this case, there were insufficient materials within the classroom to meet poor students’ needs. For example, even basic supplies, such as paper and pens, were lacking, making it difficult for students to achieve. In addition, there were various competing distractions outside of the classroom, including high rates of prostitution, arson, sexual assault, and homicide, that posed special challenges for students.

Ethnography Relies on Participant Observation

Ethnographers often employ a research strategy called participant observation, or what anthropologist Clifford Geertz (1998) called “deep-hanging out.” In this strategy, the researcher joins a group of interest for an extended period to observe and study its members and functioning first-hand. Participant observation is also sometimes referred to as naturalistic observation and fieldwork, but there are differences between these terms. Fieldwork is the general term for any research conducted in a natural setting, such as a qualitative researcher conducting in-depth interviews with participants in their homes. Naturalistic observation is a descriptive approach where observations take place in a natural setting (Cozby et al., 2020). Participant observation is one of the techniques that may be used to carry out naturalistic observation. Participant observation as a data collection method requires a researcher to join a group of interest and actively participate in that group over time to study it. Not all observation entails direct participation with group members, as discussed in the following section.

An Ethnographer’s Role During Fieldwork

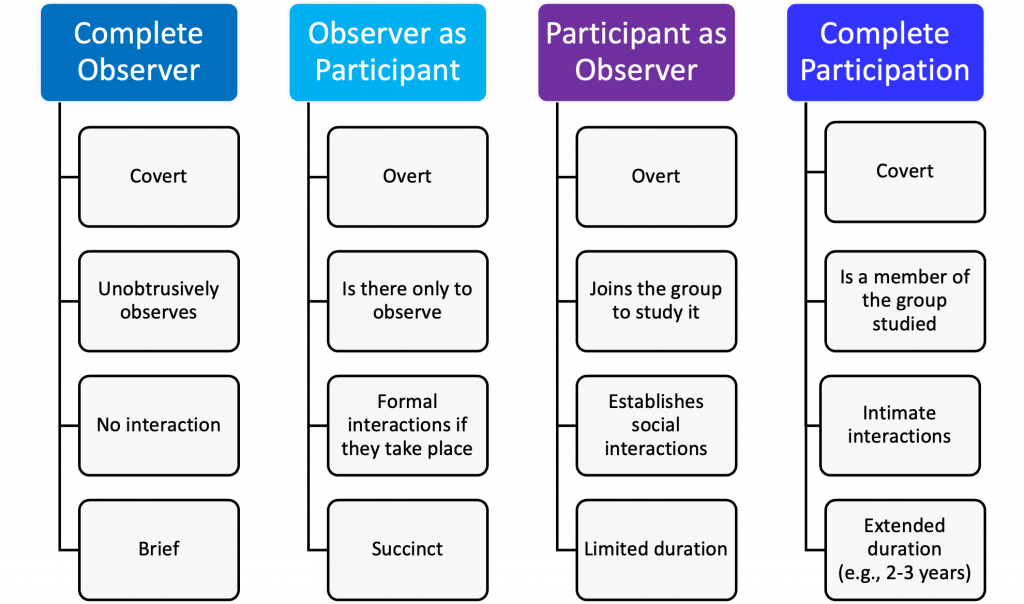

An ethnographer’s level of participation while engaged in fieldwork can range from complete observer with no active participation through to complete participation as a member of that community or culture. Gold (1958) identified a continuum for participation as illustrated in four ethnographer roles: complete observer (no participation), observer as participant (minimal participation), participant as observer (increased participation), and complete participant (full participation), as shown in figure 10.1.

Complete Observer

As a complete observer, the ethnographer’s role is to unobtrusively observe a group as a non-member who does not participate with the group in any way. For example, an ethnographer might set up recording equipment in advance of classes in order to videotape students during class lessons so the videos can be examined as part of an exploration into class dynamics. This example illustrates a qualitative approach if the variables of interest emerge from the observations, such as patterns of interaction that become apparent from content analyses of the videotaped sessions. A complete observer role may also entail systematic observation using a quantitative approach called structured observation, which is direct observation “using categories devised before the observation begins” (Bell et al., 2022, p. 139). For example, Zetou et al. (2011) examined feedback provided by Greek National League volleyball coaches to athletes during the 2010–2011 championships. Researchers videotaped practices and then coded the frequency of the following 12 types of feedback based on standard instrument called the Revised Coaching Behaviour Recoding Form: technical instructions, tactical instructions, general instructions, motivation, rewards/encouragement, comments, non-verbal punishment, criticism, demonstration, non-verbal reward, humour, and non-coding behaviour. Results indicated that any given practice session included about 279 separate coaching behaviours, with tactical instructions being most prevalent (17.4 percent), following by general instructions (15.9 percent) (Zetou et al., 2011).

Observer as Participant

In an observer as participant role, the researcher’s role is brief. For example, an ethnographer might sit in on one or two classes to observe and code student dynamics. During these observational periods, the students will be aware that the researcher is present, but the researcher’s role does not entail direct involvement with group members, so it is minimally intrusive. After a few minutes, the students are likely to forget the novel researcher collecting data and behave as they usually do. In comparison, the complete observer role is wholly unobtrusive.

To carry out structured observations in a complete observer or an observer as participant role, decisions must be made ahead of time with respect to the type of behaviour examined, the way the behaviour will be recorded, and the format in which the data are to be collected and encoded (Judd et al., 1991). Beginning with the selection of the behaviour observed, a researcher might focus on any aspect of an interaction, event, or behaviour deemed to be relevant to the research interest. In the example used earlier, the volleyball coaches’ verbal and non-verbal feedback provided to the athletes was selected for systematic observation. Next, it is important to determine whom to sample for the behaviour of interest. In the coaching example, the researchers selected 12 experienced coaches from the top divisions.

It is also important to determine how to observe the behaviour of interest and in what format. In this example, video recordings were made of each training session, with the coaches wearing wireless microphones so the researchers could examine verbal comments and non-verbal gestures. Each training session was recorded in its entirety for the 2010–2011 season of play. The video/audio recordings were then systematically examined for coaching behaviours. Each separate instance of coaching feedback was considered a new event and was encoded into one of the predetermined categories (Zetou et al., 2011). This method of collecting observations is called continuous real-time measurement because every instance of the behaviour that occurs during a particular time frame (in this case a practice session) is included in the observations. When it is difficult to determine when a behaviour begins and ends, or behaviour is going to be observed over long periods of time, researchers sometimes opt for time-interval sampling, where observations are made “instantaneously at the end of set time periods, such as every 10 seconds, or every sixth minute or every hour on the hour, with the number and spacing of points selected to be appropriate to the session length” (Judd et al., 1991, p. 279). In this case, only behaviour taking place at the end of the time interval ends up being included as part of the data collected.

Finally, it is important to decide upon a method for encoding the observations. Like the data-reduction coding schemes used in content analysis, encoding is a process used to simplify observations by using categorizations (Judd et al., 1991). Volleyball coach feedback was encoded into one of the 12 coaching behaviour categories indicated earlier, including as one of the categories, “non-coding behaviour” for the few instances that did not fit the other 11 prescribed categories (Zetou et al., 2011).

Participant as Observer

If an ethnographer joins the group to study it over a prolonged time and will interact with that group, then the researcher is engaged in a participant as observer role. For example, an ethnographer interested in a subculture such as a weekly poker session might join in, identifying themself as a researcher and as a card-playing member to become immersed in the group over the course of several weeks. In a participant as observer role, the ethnographer directly interacts with members of the group in a somewhat informal role that permits the establishment of communication and relationships while studying group members.

As another example, McNeil et al. (2015) carried out an ethnographic study on an unsanctioned safer smoking room (SSR) in Vancouver, British Columbia, to learn more about how an SSR shapes crack-smoking practices. Researchers conducted 23 in-depth interviews and spent about 50 hours engaged in participant observation with crack cocaine users at an SSR run by the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users. Findings revealed a high demand for the SSR due to factors such as homelessness and poverty that otherwise lead addicts to use drugs in unregulated public spaces where they face additional harms, including drug scene violence and crack-pipe sharing.

Complete Participant

Finally, in a complete participation role, ethnographers fully immerse themselves in the group as one of the members for a prolonged time to study the group. To lessen reactivity, the research usually takes place in a concealed manner such that the researcher’s true identity and purpose are not made known to the members. Researchers engaged in participant as observer and complete participant roles are still interested in observing behaviour (both verbal and non-verbal), people, and patterns of interaction, but the emphasis is more on understanding the subjective meanings of the observed events for the actors themselves, as opposed to coding for behaviours according to pre-established criteria. “Participant observation gives you an intuitive understanding of what’s going on in a culture and allows to you speak with confidence about the meaning of the data” (Bernard, 2018, p. 283). For example, anthropologist and motorcyclist Daniel Wolf joined an outlaw motorcycle club called the Rebels to study the group dynamics and activities from within the group for his Ph.D. research while studying at the University of Alberta in Edmonton (Wolf, 1991). As Wolf (1991) put it, “in order to understand the biker subculture, or any culture for that matter, one must first try to understand it as it is experienced by the bikers themselves. Only then can one comprehend both the meaning of being an outlaw and how that meaning is constructed and comes to be shared by bikers. Only by first seeing the world through the eyes of the outlaws can we then go on to render intelligible the decisions that they make and the behaviours that they engage in (p. 21).

Data collection in situ is very difficult to undertake since it involves finding creative ways to discreetly observe, take notes, and record conversations and events in a manner that is not obvious to those who are present at the time. Imagine what would happen in a conversation with one of your friends if you suddenly pulled out a notebook and starting writing down things the person was saying to you. Field notes, however, are critical in ethnographic research since the notes ultimately become the data that are later used to describe and explain the setting, people, and relationships under investigation. As difficult as it may be to record notes, “No observation is complete until those notes have been done” (Palys & Atchison, 2014, p. 211). At a minimum, field notes should detail relevant people, conversations, and events and indicate the date, time, and location for each observation.

Ethnography is Usually Undertaken by a Single Principal Investigator

In most cases, ethnographic fieldwork is carried out by a single principal investigator, such as Daniel Wolf’s study on the Rebels and William Foote Whyte’s study of an Italian slum. More recently, sociologist Fiona Martin (2011), from Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, interviewed 21 habitual drug users who were pregnant or were young mothers, as part of a larger ethnographic study carried out over a two-year period in a treatment clinic for women with substance use issues. Martin (2011) found that, while most addicts were trying to overcome their addictions, they faced various barriers such as established drug identities and the absence of non-drug-using relationships.

Ethnography Involves Long-Term Acquaintances

Since the goal of ethnography is to provide an accurate account of a culture or group, it is important to be around that group long enough to establish relationships with group members. The researcher needs to be in a position that permits an understanding of relationship dynamics and how members view the events and activities they engage in. Not surprisingly, ethnographers tend to spend long periods of time in the field. How long is long enough? The amount of time largely depends on what the research interest entails, including the complexity of the study, how difficult it is to access the setting, how long it takes to get to know people in that setting, and how skilled the researcher is. A study could be carried out in a few weeks, or it could take several years to complete. It is common for field research to take place over a period of about 18 months to two years. During this time, the ethnographer will initiate and develop several contacts, form friendships, and establish intimate relationships. After all, who would you be more likely to disclose personal details of your life to, a stranger or a friend? Getting to know others takes time, so it is probably better to spend more rather than less time in a field setting, for the sake of data quality. H. Russell Bernard (2018) explains:

It may sound silly, but just hanging out is a skill, and until you learn it you can’t do your best work as a participant observer.… When you enter a new field situation, the temptation is to ask a lot of questions to learn as much as possible as quickly as possible. There are many things that people can’t or won’t tell you in answers to questions. If you ask people too quickly about the sources of their wealth, you are likely to get incomplete data. If you ask too quickly about sexual liaisons, you may get thoroughly unreliable responses. Hanging out builds trust, or rapport, and trust results in ordinary conversation and ordinary behaviour in your presence. Once you know, from hanging out, exactly what you want to know more about, and once people trust you not to betray their confidence, you’ll be surprised at the direct questions you can ask. (p. 293)

Ethnography is Non-Judgmental

Although ethnographers can never be truly objective by being completely detached from the research process, and they may even be active, contributing members of groups, they still strive to be analytical and non-judgmental in their opinions and evaluations of groups and group behaviour. As Wolcott (2010) notes, “the ethnographer wants to see how things are, not to judge how they ought to be” (p. 92). Similarly, anthropologists Lavenda et al. (2023) note that they aspire to cultural relativism, “the ability to interpret specific beliefs and practices in the context of the culture to which they belonged” (p. 41). Researchers are still going to have their own opinions, and their views are not value-neutral. However, researchers strive to maintain a distinction between their personal views and their perceptions of what is going on in the observational setting. For example, an ethnographer may create several different kinds of field notes about the same event, including quick short-form “jotted notes” taken in the moment; highly “detailed notes” that resemble interview transcriptions and include, where possible, direct quotes or words and expressions used by the group members; “analytical notes,” where a researcher attempts to give meaning to what was observed; and “personal notes” that are more like journal entries that can include information on a researcher’s personal feelings toward members of the group (Wolfer, 2007).

Ethnography is Reflexive

In ethnographic research, the researcher is the data instrument—that is, it is the researcher who observes, participates, listens, records, and otherwise takes notes of events as they are occurring within the research context. Just as siblings never remember the same event in the same way, no two researchers are likely to see, record, or interpret data in the exact same manner. Juliet Corbin and Anselm Strauss (2015) explain:

It is impossible to say that there is only one theory that can be constructed from data because qualitative data are inherently rich in substance and full of possibilities. Though participants speak about a topic, they don’t determine the perspective or lens through which the analyst will interpret it. It is possible for different analysts to arrive at different conclusions even about the same data because each is examining the data with a different analytic focus or from a different perspective. Furthermore, the same analyst might look at the same data differently at different times. In other words, data talk to different analysts in different ways. For example, interviews with persons who have chronic illnesses can be examined from the angle of illness management (Corbin & Strauss, 1988), identity and self (Charmaz, 1983), and suffering (Morse, 2001, 2005; Riemann & Schütze, 1991). (p. 68)

Ethnography is reflexive because the product of the research is necessarily influenced by the perceptions of the researcher and the processes enacted by that researcher as part of the data-gathering fieldwork (Davies, 2008). Reflexivity is often described as “a turning back on oneself,” “a process of self-reference,” and/or a “self-reflection” in which an individual researcher considers the ways in which their own subjectivities and values may have influenced the research outcomes (Davies, 2008, p. 7). All qualitative research requires some degree of reflexivity since data on its own is devoid of meaning. Since it is through interpretive data analysis that researchers make sense of their observations, it is important for researchers to recognize their unique perspectives and acknowledge how such perspectives come to bear upon the research process and the meanings that result from it.

Ethnography is Mostly Descriptive

“Descriptive notes are the meat and potatoes of field work” (Bernard, 2018, p. 316). Most of the techniques used to collect field data generate enormous amounts of information. For example, interviews are transcribed into descriptive field notes. Overheard conversations may be jotted down as notes. Observed practices, customs, processes, and interactions are detailed in descriptive field notes. Wolcott (2010) advises ethnographers to err on the side of “thick” rather than “thin” description because one of the “best ways to be non-evaluative is to be intensively descriptive, to attend to what is, and what those in the setting think about it, rather than become preoccupied with what is wrong, or what ought to be” (p. 103). The goal of the ethnographer is to try to understand the meaning of this data for the participants. To achieve this, Corbin and Strauss (2015) advise researchers to begin examining data as soon as it is collected, such as after an interview is completed or an initial observation is made. Continuing in this fashion throughout the duration of the study enables “researchers to identify relevant concepts, validate them, and explore them more fully in terms of their properties and dimensions” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 69). This also prevents the researcher from being overwhelmed with data at the end of a study when it may be too late to further investigate important themes or validate findings. As Fetterman (2019) argues, the very “success or failure of either report or full-blown ethnography depends on the degree to which it rings true to natives and colleagues in the field. These readers may disagree with the researcher’s interpretations and conclusions, but they should recognize the details of the description as accurate” (p. 13).

Ethnography is Case-Specific

Ethnographic research takes place at a particular time, in a particular place, with a particular group within a particular setting. Purposive or theoretical sampling is usually used to obtain the most relevant case (group or setting), given a specific research interest. Alternatively, it could also be that only a certain group is accessible by a given researcher, and this would more closely approximate convenience or availability sampling. Either way, the group is not a representative sample and the results are unlikely to generalize beyond a given case. However, the specific focus on a single case or setting is precisely what facilitates an in-depth study that produces the rich, detailed, and authentic understanding that lies at the heart of ethnography (Hammersley & Atkinson, 2019).

Also, in ethnography, while a case generally refers to the group or setting studied, the researcher is most interested in what goes on within that setting. As a result, data are obtained on individuals, activities, rituals, processes, and so forth, rather than one person, as in a single case. To avoid confusion, Gobo (2011) suggests researchers use the terms instance or occurrence when describing various events that go on within a given setting.

Ethnography Requires Multiple Techniques and Data Sources

While ethnographic research primarily involves participant observation, details of the group and setting are obtained through any number and combination of specific techniques, including observational analysis, in-depth interviews, field notes, documents, photographs, and visual recordings. Observational analysis and field notes have already been discussed in detail in earlier sections of this chapter, while in-depth interviewing is the subject matter of chapter 9 and documents are part of the unobtrusive measures in chapter 8. Photographs are used in various ways in ethnographic research. A researcher might take a picture of a group, event, or setting to visually depict certain aspects of the stimuli that might not be captured as eloquently by descriptive notes, such as the implications of crowding, the extent of cultural diversity, or the elaborate detail on clothing. However, photographs are much more than visual aids, and anthropologists and other researchers rely upon visual ethnography as a means for understanding human behaviour and culture. For example, John Collier, Jr. and Malcolm Collier (1986) explain how photographs can be used within data collection methods such as in-depth interviewing to help facilitate communication:

Psychologically, the photographs on the table performed as a third party in the interview session. We were asking questions of the photographs and the informants became our assistants in discovering the answers to the questions in the realities of the photographs. We were exploring the photographs together. Ordinarily, note-taking during interviews can raise blocks to free-flowing information, making responses self-conscious and blunt. Tape recorders sometimes stop interviews cold. But in this case, making notes was totally ignored, probably because of the triangular relationship in which all questions were directed at the photographic content, not at the informants (pp. 105–106).

Skilled ethnographers sometimes incorporate photographs into interviews as focal points to help establish rapport and to keep interviews on track, much in the same manner as transition questions and probes.

Visual ethnography is a term used to describe the visual representation of a culture as depicted in film. Ethnographers may use visual recordings for various types of observational analyses, such as structured observation in a complete observer role, as discussed earlier. Video recordings can also be used to capture and represent a culture on film. Ethnographic documentaries are a popular means for portraying a culture or group in its natural setting through visual representations and participant accounts.

Research in Action

People of a Feather

People of a Feather, produced by Joel Heath and the community of Sanikiluaq in 2011, is a multiple-award-winning documentary about the way of life of the Inuit peoples on the Belcher Islands in the Hudson Bay area. This visual ethnographic study of the Arctic takes place over seven winters. Learn how the residents live and survive challenges, especially those arising from the hydroelectric dams that have implications for sea currents and the ecosystems tied intricately to them.

Activity: Main Features of Ethnography

Test Yourself

- What is the main assumption shared by ethnographers?

- What 10 features exemplify an ethnographic study?

- Which of the four ethnographer roles identified by Gold (1958) involve the researcher as a member of the group?

- Why is ethnography considered to be reflexive?

ETHNOGRAPHIC FIELDWORK

While ethnographic research will vary depending on the research interest, the group studied, and the methods used during fieldwork, the main stages of any ethnographic field project will include accessing the field, dealing with gatekeepers, establishing relations, becoming invisible, collecting data, and exiting the field.

Accessing the Field

First, a researcher must be able to enter the group of interest for a study. Depending on the nature of a group or setting, as well as the researcher’s own characteristics, access can be a relatively open, straightforward, and uneventful process, or it may be a highly restricted, difficult, and even dangerous process. Entering the field of study is crucial for the researcher to be able to examine the group in its natural setting and for the researcher to establish relationships needed to begin to acquire an insider’s view of what is going on.

In 1965, R. A. Laud Humphreys embarked upon a field study of illegal and impersonal homosexual exchanges among males in park public washrooms for his doctoral research. Because Humphreys was interested in learning about the practices and rules surrounding the heterosexual behaviour of men who otherwise had no “homosexual identity,” he needed to find a way to be included in the secret exchanges designed to maintain privacy (Humphreys, 1970). To accomplish this, Humphreys posed as a “voyeur-lookout”—someone interested in homosexual exchanges but not a direct participant who could help alert the participants to potential detection by police or unsuspecting passersby. Thus, Humphreys carried observational analyses in the field as a covert deviant. In his role as a participant observer, Humphreys discovered that silence was the main feature of the environment used to uphold privacy. That is, the men who had impersonal sex in tearooms (the name for public washrooms in which known exchanges took place) did so in silence specifically to ensure that the interaction was limited to that secret exchange and would not in any way impede on their regular lives, which included wives, children, and so on.

Note that, even before he ever posed as a voyeur, Laud Humphreys had to learn about homosexual men so that he would be able to later pass himself off as one. He notes that “homosexuals have developed defenses against outsiders” (Humphreys, 1970, p. 24) and he therefore underwent considerable preparation to learn about what was then considered to be a “deviant subculture” so that he would be able to join it. For example, while in clinical training at a psychiatric hospital, he got to know homosexual patients, and while serving as a pastor in parishes in Oklahoma, Colorado, and Kansas, he counselled “hundreds of homosexuals of all sorts and conditions.” He also visited “gay bars” and observed “pick-up operations in the parks and streets” (see Humphreys, 1970, pp. 23–26).

One of the more straightforward (and less time-consuming) means for accessing a group and navigating within it is through one of the existing group members. Fetterman (2019) claims an “introduction by a member is an ethnographer’s best ticket into the community.” Regardless of who the specific member is in terms of social standing or specific role, as long as the person has some “credibility with the group—either as a member or as an acknowledged friend or associate … the trust the group places in the intermediary will approximate the trust it extends to the ethnographer at the beginning of the study” (p. 47). This was the fortune of William Foote Whyte, who had an automatic entry into the group through Doc, as Doc explains,

You won’t have any trouble. You come in as my friend. When you come in like that, at first everybody will treat you with respect. You can take a lot of liberties, and nobody will kick. After a while, when they get to know you, they will treat you like anybody else—you know, they say familiarity breeds contempt. But you’ll never have any trouble. (Whyte, 1994, p. 68)

In cases where it is not possible to first get to know an existing member of the group who can serve as an entrance guide, a researcher might need to assume a more covert role, pretending to be a full member to gain inside acceptance based on membership status (Lune & Berg, 2021).

Dealing with Gatekeepers

Most groups and research settings are formally or informally “policed” by gatekeepers. Gatekeepers refer to “people who have power to grant or deny permission to do a study in the field” (Bailey, 1996, p. 149). Gatekeepers can control access to a setting in a formal or informal capacity, and there may be several gatekeepers in any given setting. For example, when I conducted my dissertation research on low self-control among sex offenders, as identified by information contained in patient files for inmates who had previously undergone treatment for sexual offending at Alberta Hospital in Edmonton, formal gatekeepers included the institutional manager, the program supervisor, and the psychiatrist in charge of sex offender treatment. In addition, once I gained approval from the formal gatekeepers and was granted ethical approval from the hospital and the University of Alberta, I still had to negotiate access to the data from an informal gatekeeper who managed the research database containing variables I wished to include in my study as well as another informal gatekeeper who managed the records department where I needed to verify information contained in the database against original documents.

Whenever possible, interactions with gatekeepers should be honest and overt. Even in the case of covert participation roles, gatekeepers are generally fully aware of who the ethnographer is and what the research objectives are. This is an important consideration, since gatekeepers are in positions where they can vouch for the researcher’s presence, aiding in the establishment of relations within the field (Wolfer, 2007).

Establishing Relations

Even with an introduction into the community and the successful negotiation past gatekeepers, the intricacies of fieldwork have barely begun. To gain a true insider perspective, an ethnographer must spend a considerable amount of time in a setting and be skilled at establishing and maintaining relations with various group members while living alongside or spending time in that setting. Gaining the acceptance of a group will be dependent on any number of considerations, including a researcher’s personal characteristics, such as age, sex, or ethnicity as well as professional attributes, such as experience, social skills, and/or demeanour.

Cultures and subcultures tend to develop their own patterns, rituals, rules, and specialized language that may not be readily understood by an outsider, even by someone who is specifically attempting to learn the language and customs to gain an insider’s view. Key insiders, also called sponsors, can be especially helpful to an ethnographer who is learning who people are and how things operate. A key insider is “a member of the setting who is willing to act as a guide or assistant within the setting” (Bailey, 1996, p. 55). Key insiders are often people who initially befriend the ethnographer and are willing to help the ethnographer understand the nuances of the setting, such as informal norms and specialized jargon. Ernest Pecco, known as Doc, helped William Foote Whyte understand all of the intricacies of the world he was immersed in, as evident in his warning admonishment:

Go easy on that ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘why’, ‘when’, ‘where’ stuff, Bill. You ask those questions and people will clam up on you. If people accept you, you can just hang around, and you’ll learn the answers in the long run, without even having to ask the questions. (Whyte, 1994, p. 75)

Due to their existing status within the culture or group, insiders are invaluable for helping the ethnographer to better understand the setting and the roles of the individuals in it.

Becoming Invisible

The primary goal of the ethnographer is to observe and describe the setting and its participants without affecting them. To accomplish this, a researcher needs to find a way to blend in with the group they are studying so that members will act naturally around the researcher and view the researcher as an insider. Stoddart (1986) suggests the ethnographers immerse themselves within the community using an invisible presence that is created through disattending or misrepresentation. Stoddart goes on to describe six potential ways to achieve invisibility while engaged in fieldwork (1986, pp. 109–113), adapted as follows:

- Disattending with time. Recall that most field studies are carried out over a considerable length of time. When a researcher first joins a group, their presence is obvious and visible. However, over time, members will begin to accept the researcher’s presence and will eventually habituate to their presence, failing to take special notice. When members fail to notice the researcher, we can say they are “disattending” and that the researcher now has invisible status within the community.

- Disattending by not standing out. Stoddart (1986) claimed it was important for an ethnographer to fit in with the group members by making sure there was “no display of symbolic detachment” (pp. 109–110). This means an ethnographer needs to look, act, and sound like the rest of the group to fit in. An ethnographer wearing a suit is less likely to fit in with a group of children on a playground than someone who is dressed more appropriately for digging in the sand or playing soccer. Similarly, someone who wishes to study street prostitutes would need to be familiar with the language, norms, and practices of the sex trade.

- Disattending by participating in the group. In addition to trying not to stand out, an ethnographer can achieve invisibility by actively participating with the group members in their everyday routines. For example, an ethnographer studying school-aged children can become a playground supervisor during recess, a lunch hour classroom monitor, or an assistant for art projects.

- Disattending by establishing personal relationships. In this case, ethnographers can elicit information and support from group members on a personal level rather than a professional one. As Stoddart (1986) put it, “the ethnographer was invisible insofar as informants suspended concern with the research aspect of [the ethnographer’s] identity and liked [them] as a person” (p. 111).

- Misrepresentation involving the research purpose. Another way that researchers can achieve invisibility is using deception. An ethnographer may, for example, identity themself as a researcher but fail to disclose all of the study’s details, or an ethnographer may misrepresent details about the true nature of the study.

- Misrepresentation involving the researcher’s identity. In some ethnographic studies, the researcher adopts a covert participant observation role, perhaps posing as a potential recruit to the group, a new hire to the organization, or a returning member of the existing community.

While becoming invisible supports an ethnographer’s need to blend into the environment to better study the setting and its inhabitants, an ethnographer’s role as an observer also warrants ongoing consideration while engaged in fieldwork. Recall the earlier discussion of the ethnographer as the data collection instrument and ethnography as a reflexive method. Reinharz (2011) suggests that there are three main selves operating simultaneously in the field, including a “research self,” a “personal self,” and a “situational self” (p. 5). The research self largely reflects the ethnographer role, which is focused on gathering data. The personal self consists of individual characteristics, such as age, gender, and existing belief systems that the researcher brings to the setting. Such characteristics influence the kinds of relationships that develop while in the setting, and they can even affect how events and observations are interpreted by the ethnographer. The situational self is the insider or member position that develops in response to specific events and group interactions that take place while immersed in the setting. Reinharz (2011) notes that by recognizing these selves in her own field research on aging in a kibbutz (an agriculture-based community in Israel), she was also able to recognize who she was not. “For example, in this study of aging, I, myself, was not an elderly women. This fact probably affected what I understood and how people related to me” (p. 205).

Collecting Data

While the essence of ethnography is listening and observing in the field in an ongoing and extensive capacity to achieve understanding, the final product of ethnographic research is generally a written document. Hence, an ethnographer records detailed field notes at every available opportunity. Field notes are detailed records about what the researcher hears, sees, experiences, and thinks about while immersed in the social setting. To an ethnographer, “field notes are the qualitative equivalent to quantitative researchers’ raw data” (Warren & Karner, 2015, p. 114). After taking the initial field notes, an ethnographer reviews the notes and records additional reflexive thoughts and observations on a regular basis, using audio recordings as well as further journal entries. To distinguish field notes from analytic notes that a researcher makes as they begin to interpret the data, Schatzman and Strauss (1973) recommend preparing three different kinds of notes, including (1) observational notes, which are the highly detailed notes written about the actual events made while still in the field; (2) theoretical notes, which are based on the researcher’s interpretation of events, including hunches, analytical insights, and initial attempts to classify the information into concepts; and (3) methodological notes, which are procedural details about how observations were carried out.

To accompany their field notes, researchers may conduct various informal interviews that are later transcribed or summarized in a written format. While in the field, researchers may even supplement or substantiate information obtained in interviews with data gathered through other methods, such as focus groups or surveys. Ethnographers can also employ visual aids—such as photographs, video recordings, sketches, and maps—to describe the setting and provide details of interactions, processes, and events going on in that setting.

Data analysis often begins while still in the field as an ethnographer examines and re-examines notes, looking for ways to best describe processes, to locate ideas within existing theoretical frameworks, and to identify emerging ideas, patterns, and themes. Data analysis continues long after the ethnographer has exited the field.

Exiting the Field

Just as entering the field and establishing relationships must be carefully negotiated, ending relationships and leaving the group is also a process that can be relatively smooth or highly problematic. An ethnographer will often plan for a gradual disengagement or look for a natural ending to a process or project occurring within the community to provide closure to the various relationships involving the ethnographer. Warren and Karner (2015) suggest, as a rule of thumb, that it is time to leave the field when “your observations are no longer yielding new and interesting data” (p. 96). Although an ethnographer may realize from an objective, data-driven perspective that it is time to leave the field, disengaging from the setting and people with whom one has spent a great deal of time can be difficult on a more personal and social level.

Test Yourself

- Why is it important to identify gatekeepers?

- How do key insiders help researchers establish relations?

- What four techniques can be used to achieve disattending?

- How does misrepresentation help a researcher to become invisible in the field?

Research on the Net

The Journal for Undergraduate Ethnography

The Journal for Undergraduate Ethnography (JUE) is an online journal that publishes ethnographies carried out by undergraduate students in a variety of disciplines as part of their course work. The journal was started in 2011. In its first issue, you can learn about a community, based on an ethnographic study of a historical cemetery; why people engage in “freeganism,” wherein they eat and recycle garbage from dumpsters; how sex offenders view themselves; and how women in relationships with incarcerated men view the criminal justice system, among other interesting topics.

For additional research based on ethnographies, also see the Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research and the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Informed Consent and Deception

In contrast to methods such as experiments and surveys, where participants sign an informed consent statement outlining the main features of study, including expectations regarding the participants’ role and the true purpose of the study, informed consent in ethnographic fieldwork is not always possible ahead of time. This poses special challenges for ethnographers and members of research ethics boards who need to weigh out the potential risk to participants of withholding information against the need to use deception to establish natural relations with group members.

On the one hand, it can be argued that informed consent is not necessary or even desirable in the case of fieldwork. This is because fieldwork takes place in a natural setting, and the behaviours and processes are going to take place irrespective of whether a researcher is studying them (Bailey, 1996). In addition, a covert approach may be preferable to lessen the potential for research-induced reactivity (Douglas, 1979). Finally, since deception exists in real-life interactions, it may also be necessary in research to study groups, particularly ones engaged in illegitimate activities (Bailey, 1996).

On the other hand, we ask ourselves, is it ethical or morally acceptable to knowingly deceive participants to study them? Bailey (1996) notes that, for example, “a premise of a feminist ethical stance is that the process and outcomes of field research are greatly affected by the reciprocal relationships that develop between the field researcher and those in the setting” (p. 13). From this perspective, it would be unethical to use deception to achieve what a researcher hopes will become open and honest relationships with group members. Moreover, if a researcher is upfront about their position and objectives, it may be even more likely that a group will come to trust the researcher. Since outsider status is often obvious to group members, attempts to cover the newcomer’s identity may lead to mistrust and inhibit the establishment of relationships. A researcher’s outsider status may even afford group members the additional liberty to ask naive or blunt questions or to provide highly insightful responses that would not be characteristic of insider relations (Bailey, 1996).

One way to resolve the dilemma of choosing between informed consent versus the need for deception in field research is to conceptualize consent as an ongoing process rather than an initial step or one-time document. In this case, there may be alternatives, such as an alteration of documentation of informed consent, which refers to “an informed consent discussion with every subject” as opposed to a written, signed statement of informed consent listing all risks and requirements of participation in a study (Scott & Garner, 2013, p. 61). Another option is a step-wise consent process in which you (as the researcher) “describe roughly how you’re going to enter the community or group, how and when you’re going to first describe what you’re doing and what their involvement will consist of as subjects, and so forth” (Scott & Garner, 2013, p. 61).

Maintaining Privacy

Due to the personal nature of the insider information collected during fieldwork, an ethnographer needs to carefully consider how issues of privacy relate to the research project in its entirety and what the researcher’s own accountability is when it comes to maintaining the privacy of respondents. First, while a researcher may attempt to maintain confidentiality by leaving out names or by using pseudonyms for information that will appear in print, the descriptions, quotes, or illustrations used may still identify participants or groups to others based on the nature of the information revealed. In such cases, researcher may have to take further measures to disguise the identity of participants by changing the age and sex of the participants or by modifying their roles to protect them from potential privacy violations and their subsequent harm.

In describing globalizing feminist research, Mendez (2009) points out that privacy and accountability issues can be especially problematic because

there is no single homogenous community to which the researcher is accountable, but rather multiple groups, communities, organizational and international levels, and conflicting interests. It is within these often intersecting and sometimes conflicting communities that the researcher and those she is studying must negotiate mechanisms of accountability. (p. 87)

For example, while studying labour mobility, Mendez encountered women whose undocumented immigration status, if known, would result in incarceration or deportation. She also spoke with outreach workers who were highly sensitive about their lack of decision-making authority within the larger organizations and higher-level administrators who were reluctant to share information that would negatively reflect on their own or other organizations. Given established relations at various levels within and between groups, an ethnographer needs to keep in mind what information is obtained, how that information will be shared, how that information will be received, and what the repercussions might be as a result.

Risk of Harm to the Researcher

Field research, because of its inherent naturalness, presupposes a level of unpredictability that can pose a risk of harm to researchers. An ethnographer who infiltrates an outlaw motorcycle club known for its reliance on violence as a means for resolving conflict is going to be at risk for physical danger. Similarly, an ethnographer who joins a travelling carnival to understand what life is like for members of that subgroup is likely entering a setting that contains many yet-to-be-discovered illegal behaviours and questionable practices that may inadvertently pose risks to any insider. Then again, it is precisely the use of first-hand observation in a natural setting that produces highly valid representations and conclusions.

Activity: Ethical Considerations Key Terms

Test Yourself

- Why might an ethnographer oppose the need to obtain informed consent?

- What are two alternatives to obtaining informed consent prior to the onset of fieldwork?

Research in Action

JOHAR

JOHAR: An Ethnographic Documentary on Santhals (2020) produced and directed by Abhijit Patro, is an ethnographic study on an ethnic group called the Santhals, a tribal community in India posted to YouTube on August 21, 2020.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- Define ethnography and describe the role of an ethnographer.

Ethnography is a methodology for studying a social group or culture based on observation. An ethnographer systematically studies a group by observing it and by participating in it. - Outline the main features of ethnographic studies.

Ethnographic studies usually include the following 10 features:- Ethnography takes place in natural settings.

- Ethnography is context-based.

- Ethnography relies on participant observation.

- Ethnography is undertaken by a single principal investigator.

- Ethnography involves long-term acquaintances.

- Ethnography is non-judgmental.

- Ethnography is reflexive.

- Ethnography is mostly descriptive.

- Ethnography is case-specific. Ethnography takes place in natural settings.

- Ethnography requires multiple techniques and data sources.

- Differentiate between the four main roles of ethnographers engaged in fieldwork.

As a complete observer, an ethnographer observes a group but is not in the group and does not participate with the group in any way. In an observer as participant role, the researcher systematically observes a group but is not a group member and only interacts indirectly with the group. A researcher in a participant as observer role systematically observes a group by becoming a member to establish relationships and interact with group members. Finally, in complete participation, a researcher is already a group member at the onset of the research or becomes a group member to covertly study that group as a fully participating member over a prolonged time. - Describe the main stages of fieldwork.

To conduct fieldwork, ethnographers need to access the field, often through the introduction of existing members. In addition, ethnographers must identify and gain permission from gatekeepers, establish relations with group members, and become invisible so members stop viewing the ethnographer as a researcher and start accepting them as a group member. While in the field, researchers also collect data through a variety of techniques and eventually exit the field by disengaging from ongoing activities and relationships with group members. - Explain the techniques used by ethnographers to blend into a group.

The main method used to blend into a group is to achieve invisibility. This can occur in a variety of ways. For example, if a researcher spends a considerable amount of time with a group, the members will habituate to the researcher’s presence (i.e., disattending with time). In addition, a researcher can become invisible by not standing out, by participating in everyday routines, and by establishing personal relationships. A researcher may even use deception or adopt a covert participation role to achieve invisibility. - Discuss ethical issues in fieldwork.

Various ethical considerations arise in fieldwork, beginning with initial decisions pertaining to the need to obtain informed consent versus the use of deception in order to be accepted as a group member. Other ethical considerations relate to privacy and how to keep information provided by members confidential but still meet the research objectives and maintain accountability to various groups and individuals with sometimes competing or conflicting interests. Finally, researchers need to be aware of ongoing personal risks of harm incurred through participation in the group.

RESEARCH REFLECTION

- Over the course of a week, keep a “reflective” journal that you can use to record entries that describe conversations you had with your close friends and family members. Try to jot down details of the conversation using “thick description” (adapted from Watt, 2010).

- At the end of the week, go back over the journal entries and review the descriptions. Using “reflexivity,” identify several ways in which the conversations resulted from or show evidence of your own personal interests, values, and points of view (adapted from Watt, 2010).

- Now suppose you are an ethnographer studying group dynamics. In what ways could you change your future behaviour during interactions with the individuals described in your reflective journal to be less directing and more neutral during the conversations?

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE

Objective: To learn how to conduct fieldwork

Directions:

- Choose a well-known service provider on campus (e.g., a food provider, a library service, computer help desk).

- Visit the service provider to examine the setting from the perspective of an ethnographer planning to do a field study.

-

- Draw a map of the physical setting.

- Identify gatekeepers and describe the process you would need to go through to gain access to the setting for research purposes.

- Provide a description of any individuals you think might serve as key insiders. If you don’t know anyone in the setting, indicate who might be a potential key insider. For example, if you were studying the library borrower services, one of the employees at the circulation desk would be a potential key insider.

-

- Of the four roles ranging from complete observer to complete participation, which do you feel would be most appropriate, given your selected site? Justify your response.

- Describe a technique you think would assist you in becoming invisible in this environment.

- Visit your selected service provider/location a total of four times on two different days at two different times. Take notes each time you go and see if you can detect changes in the environment at different times or on one of the days. Describe your observations.

- What ethical issues are raised by observational studies? What can be done to address these considerations?

RESEARCH RESOURCES

- For a comprehensive guide to ethnography, see Madden, R. (2023). Being ethnographic: A guide to the theory and practice of ethnography (3rd ed.). Sage.

- For an understanding of how ethnographic research can contribute to social change, refer to Stoller (2023). Wisdom from the edge: Writing ethnography in turbulent times. Cornell University Press.

- For a guide to conducting contemporary ethnographic research, see Sahoo, M., Jeyavelu, S., & Kurane, A. (Eds.). (2023). Ethnographic research in the social sciences. Routledge.

- To learn about the experiences of Syrian refugee women as they settled in Canada, see Al-Hamad, A. et al. (2022). Listening to the voices of Syrian refugee women in Canada: An ethnographic insight in the journey from trauma to adaptation. International Migration and Integration, 24, 1017–1037.

Social scientists who undertake research and writing about groups of people by systematically observing and participating (to a greater or lesser degree) in the lives of the people they study.

A multi-method approach to field research that is used to study a social group or culture in its natural setting over time.

An in-depth study of a group or culture that exists in an online environment.

A research method in which the researcher is actively involved with the group being observed over an extended period.

A participant observation role in which the researcher covertly observes a group but is not a group member and does not participate in any way.

A quantitative approach in which behaviour is observed and coded using pre-determined categories.

An overt participant observation role in which the researcher systematically observes a group but is not a group member and only interacts indirectly with the group.

An observation-based data coding method in which every separate and distinct instance of a variable is recorded during a set observation period.

An observation-based data coding method in which variables are recorded at the end of each set time interval throughout a set observation period.

A data-reduction method used to simplify observations by using categorizations.

An overt participant-observation role in which the researcher systematically observes a group by becoming a group member to establish relationships and interact directly with the group.

A covert participant observation role in which the researcher systematically observes a group as a full member whose identity and research purpose is unknown to the group members.

The principle that people’s beliefs and activities should be understood and interpreted within the context of their own culture.

A self-reflection process in which researchers consider the ways in which their own subjectivities may have influenced the research outcomes.

Representations of culture as depicted in photographs and film documentaries.

People who have power to grant or deny permission to do a study in the field.

A member of the setting who is willing to act as a guide or assistant within the setting.

Detailed records about what a researcher hears, sees, experiences, and thinks about while immersed in the social setting.

An informed consent discussion that takes place with each participant in the setting in lieu of a signed informed consent statement.

A consent process that takes place in stages following the establishment of relationships within a group.