Chapter 11: Mixed Methods and Multiple Methods

Mixed methods research recognizes, and works with, the fact that the world is not exclusively quantitative or qualitative; it is not an either/or world, but a mixed world, even though the researcher may find that the research has a predominant disposition to, or requirement for, numbers or qualitative data.

— Louis Cohen, Lawrencee Manion, & Keith Morrison, 2018, p. 31

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

- Compare and contrast quantitative and qualitative approaches.

- Define mixed-methods approach, explain why a researcher might opt for a mixed-methods design, and differentiate between mixed-method designs.

- Define case study research and explain why a researcher might choose a single-case design over a multiple-case study.

- Define evaluation research and explain what an evaluation design entails.

- Define action research, describe the underlying logic of action research, and identify the steps in an action research cycle.

INTRODUCTION

In earlier chapters, you learned to distinguish between qualitative and quantitative approaches to social research. In this chapter, you will learn about the merits of mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches for adding depth and breadth to our understanding of just about any social topic. In addition, you will learn about various ways to combine multiple methods in a single study.

How the Approaches Differ

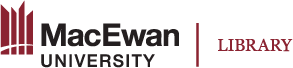

Recall how quantitative approaches tend to stem from the positivist tradition, which emphasizes objectivity and the search for causal explanations, while qualitative approaches can often be traced to a more interpretive framework, with an emphasis on the socially constructed nature of reality. In addition, while quantitative approaches are usually rooted in deductive reasoning and include research questions framed into hypotheses with operationalized variables, qualitative methods often incorporate inductive reasoning and research questions that are broader or take the form of exploratory statements about concepts of interest. There are always exceptions to these patterns, as in the case of qualitative research that is designed to test theories or quantitative research that is inductive. However, it is fair to say that the methods used by quantitative researchers often consist of experiments, surveys, or unobtrusive measures such as the analysis of secondary data, while qualitative researchers are more apt to rely upon in-depth interviews, participant observational approaches, or ethnography to examine a phenomenon in its natural setting.

Acknowledging differences between qualitative and quantitative approaches does not imply that there must be a division between them, so much as it helps to illustrate the ways in which the approaches are complementary. That is, the strengths of one approach tend to be the weaknesses of the other and vice versa. For example, a survey in the form of a questionnaire can be used to obtain a great deal of data from a large representative sample, and the measures on the questionnaire might be considered highly reliable and valid using quantitative criteria such as inter-item reliability and construct validity. However, from a qualitative perspective, the findings still might not be genuine, since they are based on predetermined categories and highly structured questions—meaning respondents cannot provide additional details or explain the issue from their own perspective. In addition, respondents may choose not to answer certain items and may provide less truthful, albeit socially desirable, answers. Conversely, the rapport established in an in-depth qualitative interview can uncover a wealth of information from the perspective of an interviewee. The insightful discoveries are deemed to be credible because of the trustworthy processes used to obtain the data as well as the rigour used to verify the findings, such as through member checks and peer debriefing. However, from a quantitative perspective, the same results are going to be viewed as having limited reliability, due to the small sample size and a lack of generalizability. Figure 11.1 provides a highly simplified comparison of the key differences between quantitative and qualitative methods. For a more detailed discussion of the various ways to assess reliability and validity in qualitative and quantitative studies, please refer to chapter 4.

How the Approaches are Similar

Although it may appear that quantitative and qualitative approaches are opposites, there is one main similarity shared by the approaches when it comes to their overall orientation to research: both qualitative and quantitative approaches rely on empirical methods. Both approaches are geared toward empirical observations even though they rely upon different techniques to obtain them. Although different methods are used, the processes undertaken follow systematic procedures that are recognized by other researchers. Qualitative researchers, for example, carry out in-depth interviews in standardized ways, by first obtaining ethical approval, by obtaining consent from the interviewee, by using opening remarks to break the ice and establish rapport, and by utilizing various types of questions and prompts. Similarly, quantitative researchers administer a questionnaire in standardized ways, by first obtaining ethical approval, by obtaining consent from the participants, by including clear instructions for completing the questionnaire, and by developing a questionnaire instrument that avoids the use of jargon and technical language. In the same way, quantitative researchers carefully create instruments so they constitute highly reliable and valid measures, while qualitative researchers go to great lengths to ensure their approaches to data collection are trustworthy and credible and that the data obtained is accurate. Moreover, when it comes to the dissemination or sharing of research findings, all researchers describe the procedures they followed to undertake the study in such detail that others can check on and verify the processes and, in some cases, even replicate the study based on how it was described. Thus, one approach is not better or worse than another—the two are just different, as required for different purposes.

Combined Approaches are Not New

Research in the social sciences is highly complex, particularly when the goal is to accurately describe a group, explain a process, or explore an experience. Relying on either quantitative or qualitative methods exclusively can be unnecessarily limiting. For example, Padgett (2012) points out that while “surveys supply much-needed aggregate information on individuals, households, neighborhoods, organizations, and entire nations … they fall short in assessing individuals as they live and work within their households, neighborhoods, organizations, and nations” (p. 9). Wouldn’t it make sense to combine approaches to achieve a more complete understanding? Research utilizing combined approaches is common in a variety of disciplines, including education, healthcare and nursing, library science, political science, psychology, and sociology (Terrell, 2012). Some approaches to research are always based on a combination of methods. Ethnography, for example, is routinely carried out using a combination of qualitative methods of equal importance within the overall design of a study, such as participant observation and qualitative interviewing, or qualitative interviews combined with elements of photography (see chapter 10). Further, methods that are primarily quantitative sometimes include a qualitative component, such as structured questionnaires that include closed- and open-ended items (see chapter 7). Some methods are conducive to both qualitative and quantitative approaches, such as content analysis and observational analysis. Finally, triangulation in qualitative research necessitates attempts to locate a point of convergence or agreement in findings as based on multiple observers, multiple data sources, or the use of multiple methods (see chapter 4). There are endless possibilities for combining methods and approaches in a single study. Methods were introduced in singular forms in earlier chapters mainly for the sake of simplicity, so you would first be able to understand their underlying logic and unique contributions. As noted in the opening quote, using a combination of approaches has the potential to describe and explain phenomena more fully and completely than could be ever be the case if researchers limited themselves to only one quantitative or qualitative method.

Activity: Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

- Why are qualitative approaches considered to be empirical?

- In what ways are qualitative and quantitative approaches complementary?

MIXED-METHODS APPROACHES

Distinct from the use of multiple methods of any kind, a mixed-methods approach always entails an explicit combination of qualitative and quantitative methods as framed by the research objectives. This can involve designing a study to include a qualitative and quantitative method undertaken at the same time, such as obtaining existing data for an organization for secondary analysis while at the same time interviewing members of that organization. A mixed-methods approach can also include the use of two or more methods at different times, such as seeking participants for qualitative interviews based on the findings from the secondary analysis of existing data.

Research on the Net

Journal of Mixed Methods Research

The Journal of Mixed Methods Research (JMMR) is an interdisciplinary quarterly publication that focuses on empirical, theoretical, and/or methodology-based articles dealing with mixed methods in a variety of disciplines. In the articles found in JMMR, you can learn more about types of mixed-methods designs, data collection and analysis using mixed-methods approaches, and the importance of inferences based on mixed-methods research.

Why Researchers Mix Methods

Researchers combine qualitative and quantitative methods for any number of reasons. The most commonly cited reason for mixing methods pertains to the comprehensive understanding of research interests that can only be obtained through a combination of different but complementary approaches (Tanoamchard, 2023). For example, after employing one method, researchers can elaborate upon or clarify the results obtained, using additional methods (Green et al., 1989). Faye Mishna and colleagues at the University of Toronto (2018) first examined the nature and extent of cyber-aggression among university students via responses provided by 1,350 students who completed an online survey. Survey findings, for example, indicated that about one-quarter of the respondents had had a video or photo shared without their permission and that perpetrators tended to be friends of the victims. The researchers later conducted a series of focus groups and interviews to better understand respondents’ concerns and identified themes of perceived anonymity and the practice of sexting as contributors to online “attacks,” and discovered cumulative mental health consequences (Mishna et al., 2018).

A second related reason for combining approaches is to capitalize on the benefits of both approaches, while minimizing or offsetting their associated drawbacks (Bell et al., 2022). Recall that an experiment is conducted in a controlled environment that lends itself to high internal validity but may be so artificial that is not representative of a real-life setting. In-depth interviews with participants can help to determine whether the findings have external validity. Finally, a researcher might also use mixed methods for development purposes where the findings from one method (e.g., qualitative) are used to help design the second method (e.g., quantitative) (Green et al., 1989). This kind of development usually takes place in what Creswell and Creswell (2023) refer to as sequential designs, where one method is used in the first phase of a study and the results then inform a different method that is used in a later phase. For example, a researcher may start off with a focus group or in-depth interviews to establish categories or to develop items that will be later utilized in a structured survey.

Mixed-Method Designs

There are various ways to mix methods within a research study, based on the order or sequence in which the methods are employed and the point (or points) at which the data are combined. Three mixed-method designs are discussed in this section to illustrate customary ways to combine qualitative and quantitative methods within a single study.

Convergent Design

In a convergent design (also known as a convergent parallel design), both qualitative and quantitative methods are employed at the same time with equal priority (Creswell & Creswell, 2023). For example, secondary analysis of existing data might coincide with interviews during the same phase of a research study. Using a convergent design, researchers carry out independent data collection and analyses where the secondary analysis is done separately from the interviews. Only at the end stage of the research are findings from the qualitative and qualitative components compared and integrated as part of the overall interpretation (see figure 11.2). Note that convergent designs are used in triangulation strategies, where more than one method is employed to see if the results converge. However, in such cases, the two methods are likely to both be qualitative, as opposed to qualitative and quantitative.

Wilson et al. (2012) employed a mixed-methods convergent design to understand the implications of care-setting transitions during the last year of life for rural Canadians. They used quantitative secondary analysis to describe and compare healthcare transitions between rural and urban residents based on in-patient hospital and ambulatory care information on Albertans that was contained in databases. At the same time, the researchers used an online survey to collect information from individuals who could provide details on rural Canadians who had died in the last year. Respondents were asked to provide information on the number of moves, the location of the moves, and the impact of care moves undertaken by the now deceased. Researchers also conducted qualitative interviews with bereaved family members, located through notices posted in rural newspapers and in community settings (e.g., grocery store bulletin boards), to learn about the moves and the family members’ experiences over the last year. Findings from the secondary data revealed that rural decedents had undergone more healthcare-setting transitions for in-patient hospital care than urban patients had. Survey data indicated that the deceased had undergone an average of eight moves in the last year of life and that there was a great deal of travelling required to take the now-deceased individuals to and from appointments, generally at different hospitals in various locations. Main themes emerged from the interviews—the point that necessary care was scattered across many places; that travelling was difficult for the terminally ill and their caregivers; and that local services were minimal (Wilson et al., 2012).

As a more recent example, Armstrong et al. (2022) employed a mixed-methods convergent design to investigate the way different blood donor policies shape interest in donation and willingness to donate among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Ontario, Canada. A series of surveys (i.e., the quantitative methods) were completed by 447 gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men along with in-depth interviews (i.e., the qualitative method) involving 31 of these individuals. Quantitative results showed that 69% of respondents were interested in donating blood and that, among this group, willingness to donate would significantly increase if the policy in place at the time of the study (i.e., the policy preventing men from donating if they had had oral or anal sex with another man) was altered to remove the consideration of oral sex or to include the consideration of condom use. However, these alternative policies did not elicit a similar quantitative increase in willingness among respondents who were not interested in donating blood. Qualitative data demonstrated that their disinterest was largely rooted in the interpretation of any policy specifically targeting men who have sex with men as discriminatory; and that these respondents would only consider donating under a policy that was applied to all prospective donors regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation (Armstrong et al., 2022).

Explanatory Design

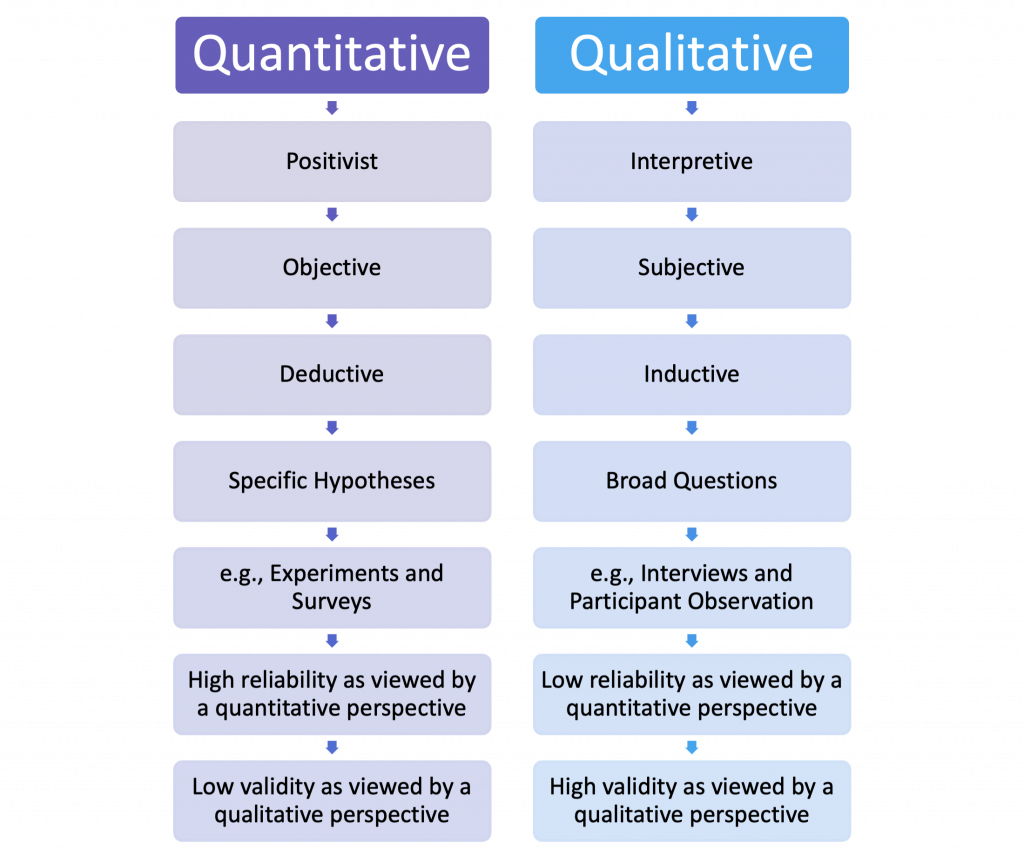

Recall that one of the main reasons for combining methods is to clarify the results of one method through the utilization of a second method. In an explanatory design (also known as an explanatory sequential design), a quantitative method is employed first and then the findings are followed up on, using a qualitative method (see figure 11.3). For example, a researcher might administer a survey to understand the general views of a sample on an issue of interest. After the survey data is collected and analyzed, researchers might conduct in-depth qualitative interviews with a few respondents to better understand and explain results obtained in the earlier, prioritized quantitative phase.

In a study on the interrelationships between bisexuality, poverty, and mental health, Ross and colleagues (2016) first examined quantitative survey data stemming from a sample of 302 bisexual individuals from Ontario. The quantitative data provided descriptive information on the sample, including demographics (e.g., age, gender identity, education, and relationship status), and it was used to develop a context for understanding poverty and mental health by examining the effect of low income, as measured by the Canadian Low Income Cut-Off (LICO), on mental health indicators such as depression and anxiety. For example, 76 participants (25.7 percent) were below the LICO, and of those, individuals who identified as “trans” were over-represented. Those below the LICO also showed higher scores for psychological distress and discrimination compared to those above the LICO (Ross et al., 2016). The researchers later followed up with 41 participants, through qualitative interviews, to learn more about how bisexuality, poverty, and mental health interrelate through pathways. For example, one pathway concerned early life experiences related to bisexuality that directly or indirectly impacted income and mental health, as was the case for participants who lost middle-class status when they left their families of origin due to conflicts relating to their sexuality, or those who turned to substance abuse as a means for dealing with their feelings (Ross et al., 2016, p. 67).

Exploratory Design

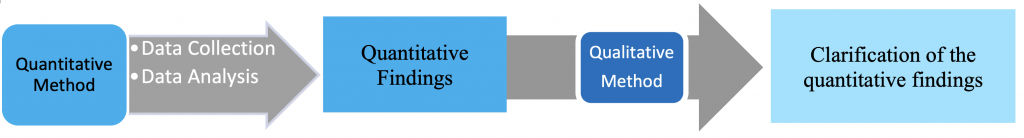

In an exploratory design (also known as an exploratory sequential design), a qualitative method is prioritized and then, based on the findings from the qualitative study, a quantitative method is developed and subsequently employed (see figure 11.4). For example, themes emerging from transcribed data based on a small number of in-depth interviewees can help to create categories and constructs included in a questionnaire for use with a much larger, more representative sample of respondents.

Moubarac et al. (2012) used a two-stage exploratory mixed-methods design to examine the situational context associated with the consumption of sweetened food and drink products in a Catholic Middle-Eastern Canadian community in Montreal. In stage 1, the researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with 42 individuals to learn more about sweetened food and drink consumption. Specifically, the convenience sample was asked to think about their consumption of sweetened drinks and foods, and they were provided with examples. Interviewees were then directed to comment on the last three times they consumed sweetened products, noting conditions and circumstances associated with consumption, such as time of day and location. In addition, the interviewees were asked to name their favourite sweetened product and to note conditions and circumstances associated with it. Finally, they were asked about customary consumption of sweetened products in different locations, such as at work and at home. A content analysis of the transcribed interview data revealed 40 items and six main themes associated with consumption of sweetened products, including energy (i.e., sweets provide energy); negative emotions, or tendency to eat sweets when sad; positive emotions, such as a reward; social environment (e.g., offered at someone’s house); physical environment or availability; and constraints (e.g., eating out at restaurants) (Moubarac et al., 2012).

Findings from stage 1 were then used to construct the Situational Context Instrument for Sweetened Product Consumption (SCISPC), a self-report questionnaire used in stage 2 of the study. Stage 2 consisted of a cross-sectional study in which 192 individuals (105 women and 87 men) completed the SCISPC. The participants also completed a food frequency questionnaire that included a listing of sweet products such as brownies, cakes, candy, cookies, muffins, and soft drinks along with the associated total sugar content, a questionnaire on socio-demographics, and items on self-reported weight and height. Quantitative analyses revealed seven situational factors related to the consumption of sweets, including emotional needs, snacking, socialization, visual stimuli, constraints, energy demands, and indulgence (Moubarac et al., 2012).

Activity: Mixed Method Designs

Test Yourself

- In what way is a qualitative approach similar to a quantitative one?

- What six core characteristics underlie true mixed-methods research?

- For what reasons might a researcher choose a mixed-methods design?

- In which kind of mixed-methods design does a researcher begin with quantitative data collection and analysis?

RESEARCH USING MULTIPLE METHODS

Within the social sciences, certain types of studies are routinely carried out using multiple methods, such as ethnography, as discussed in chapter 10. Three areas of research that typically employ multiple methods (but not necessarily mixed methods) are case study research, evaluation research, and action research.

Case Study Research

Recall from chapter 4 that a case study pertains to research on a small number of individuals or an organization carried out over an extended period. A case study is an intensive strategy that employs a combination of methods such as archival analysis, interviews, and/or direct observation to describe or explain a phenomenon of interest in the context within which it occurs. As Yin (2018) puts it, a case study is most relevant when a “how” or “why” research question is being asked about a contemporary set of events over which the investigator has little control (p. 9). The focus of a case study can be a person, a social group, an institution, a setting, an event, a process, or even a decision. In addition, the scope of a case study can be narrow, as in an examination of one person’s journey through a single round of chemotherapy treatments, or it can be broad, as in a case study of chemotherapy as an available treatment option for cancer patients. What sets case study research apart from other forms of research is that it is a strategy that intensively “investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the ‘case’) in depth and within its real-world context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context may not be clearly evident” (Yin, 2018, p. 15).

By holistically examining one person undergoing chemotherapy treatment, for example, a researcher can gain insight into the greater context of how other variables, such as interactions with doctors and hospital staff, travel arrangements, family dynamics, and pain management all contribute in various ways to the overall experience for that individual. Case study research relies upon multiple methods of data collection, with the goal of uncovering converging evidence that will help to explain or describe the phenomenon of interest. If the goal of a case study is to understand a person’s experience while undergoing chemotherapy, a researcher is likely to interview that person on several occasions and speak to primary caregivers close to that person, such as a spouse, parent, sibling, and/or child. In addition, the researcher might examine archival documents, such as postings on Facebook or entries in a personal diary, to get a sense of what the experience means to the person undergoing treatment. While most often employing qualitative methods, case studies are not inherently qualitative in nature and can include quantitative methods or a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection techniques.

Single- versus Multiple-Case Study Designs

Single-Case Design

Case study research is based on either a single-case or a multiple-case design. A single-case design refers to case study research that focuses on only one person, organization, event, or program as the unit of analysis as emphasized by the research objectives. Yin (2018) offers several reasons why researchers might choose a single-case design. First, a single-case design might be selected by a researcher if the case represents a critical case that represents all criteria necessary for testing a theory of interest. A single-case design might also be preferred if the case represents an extreme situation or event, since an outlier is likely to provide insights that are unanticipated. However, a single-case design is also likely to be chosen if a case can be identified as highly representative or common among a larger range of phenomena to convey what is typical. In addition to features of the case itself, a single-case design might be selected largely because of the unique opportunity it affords to investigate an area. For example, a case study of a patient with a rare disorder can help medical practitioners and families to more accurately describe the disorder, find appropriate interventions, and reveal new insights. This is usually called a revelatory case (Yin, 2018, p. 50). Finally, if the goal of a study is to determine how a person, organization, or process changes over time, a single-case study is a good choice, as this design is especially suited to longitudinal analysis.

As an example of a single-case strategy focused on one person, Elmhurst and Thyer (2023) jointly writing in first person perspectives as the client (Elmhurst) and therapist (Thyer), describe how exposure therapy over Skype was used to treat a 27-year old women with a debilitating fear of balloons. The study included a period of initial assessment (where the client met the diagnostic criteria for a phobia), followed by self-conducted exposure therapy where the client was slowly exposed to a Youtube video depicting balloons being popped and recorded her reactions to it over a period of time. Once the client mastered watching the videos, she was then exposed to uninflated balloons in her home and eventually exposed to balloons over Skype (where the therapist blew up and popped them). Quantitative measures included pre- and post-treatment approach measures including how close the client would come (in feet) away from a balloon as well as anxiety ratings while qualitative assessments included personal accounts (e.g., dreams and balloon ruminations). By the end of the Skype sessions, the client was able to blow up and pop a balloon herself and she no longer met the diagnostic criteria for a phobia (Elmhurst & Thyer, 2023).

As another example, Hamm et al. (2008) focused their single-case study research on a long-standing Canadian non-profit sports organization to examine value congruence between the employees and the organization. First, the researchers collected and examined existing documents, such as policy statements, meeting notes, and emails. The next phase of the study involved non-participant observation in meetings and activities. In the third phase, employees rated their personal employee values by completing the Rokeach Value Survey. Finally, employees identified as having the highest and lowest value congruence, based on the survey findings, were then interviewed to learn more about their opinions and experiences. Overall, the findings indicated a significant discrepancy or incongruence between organization and employee values. For example, while the organization emphasized “wisdom” and “equality,” the employees rated “accomplishment” and “family security” as being much more important. Moreover, while the organization highly valued “equality,” the employees did not feel that they were treated with equality. In addition, the organization heavily promoted their five core values (i.e., leadership, open, listen, responsive, and relevant), but none of the interviewed employees mentioned these as values they felt they shared with the organization (Hamm et al., 2008).

Multiple-Case Design

A multiple-case design is a case study strategy that involves more than one case studied concurrently for the explicit purpose of comparison. According to Yin (2018), a small number of cases are specifically chosen for use in multiple-case study designs because they are expected to produce similar findings, akin to replication in experimental research. Alternatively, two or more cases might also be selected because they are expected to show contrasting findings, as predicted by relevant theoretical assertions. It is important to note that the logic underlying the inclusion of additional cases cannot be likened to the sampling logic used in quantitative survey research to obtain representative samples or generalizable findings. However, it can approximate the control obtained in experimental research if the two selected cases are virtually identical except for the feature that becomes the focus of a controlled comparison (George & Bennett, 2005).

As an example of a multiple-case design, Egan et al. (2023) sought to identify factors associated with exemplary post-discharge stroke rehabilitation care through a comparison of four programs from different regions of Ontario. Semi-structured interviews with patients, care partners, and administrators as well as focus groups with care providers revealed three features in common including a high level of stroke and stroke rehabilitation knowledge, the establishment of personalized respectful relationships, and a commitment to high-quality, person-centred care (Egan et al., 2023).

Research Strategy: Case Study

To better understand how a case study differs from an experiment and to appreciate the differences between single-case and multiple-case designs within a business context, you can view Robert Barcik’s video on case study research, uploaded to YouTube on March 17, 2016.

Evaluation Research

Another form of research that relies upon the use of multiple methods for data collection and analysis is evaluation research. Recall from chapter 1 that evaluation research is undertaken to assess whether a program or policy is effective in reaching its desired goals and objectives. Social science evaluation research includes “the application of empirical social science research to the process of judging the effectiveness of … policies, programs, or projects, as well as their management and implementation for decision making purposes” (Langbein, 2012, p. 3). Virtually every government department and every funded social program or intervention undergoes evaluation. For example, evaluation research was used to determine the effectiveness of Canada’s first LGBTQ2S Transitional Housing Program (Abramovich & Kimura, 2021), a therapist training program for treatment-resistant depression (Tai et al., 2021), Before Operational Stress (a program to support mental health)(Stelnicki et al., 2021), and a community-based approach to developing mental wellness strategies in First Nations (Morton et al., 2020). The potential topics for evaluation research are endless.

Types of Evaluation Research

There are different kinds of evaluation research, depending on where a program is in terms of its existence and overall life course. For example, before a program is developed, evaluation research is informative for diagnosing what is required in the way of a program. “The main form of diagnostic research that centers on problems is the needs assessment. In needs assessment, the focus is on understanding the difference between a current condition and an ideal condition” (Stoecker, 2013, p. 109). Goals of a needs assessment typically centre on identifying a problem, finding out who is affected by that problem, and coming up with a program to address the problem. Sample questions include the following:

- What is the nature of the problem affecting this community (or group)?

- How prevalent is this problem?

- What are the characteristics of the population most affected by this problem?

- What are the needs of the affected population?

- What resources are currently available to address this problem?

- What resources are required to more adequately address this problem?

Needs assessments are largely focused on obtaining information that will help in the early planning and eventual development of a program. To learn as much as possible about members of a target community, researchers are likely to rely upon a range of tools and methods, including existing documents, survey methods, observational analyses, and interviews (Sullivan, 2001).

Evaluation research that is conducted to examine and monitor existing programs is usually called program evaluation or program monitoring. The overarching question in a program evaluation is likely to take the form of “Did the program work?” Evaluation directed at answering the question of whether a program, policy, or project worked usually entails a large-scale research project that combines multiple methods, such as site visits, the examination of existing program documents, and in-depth interviews with employees. The purpose is to gauge how well the major program components link up with the corresponding program goals.

Sample questions include the following:

- Is this program working? (Why or why not?)

- Is this program operating as it was intended?

- Are program objectives being met?

- Are the services reaching the intended target population?

- Were the program goals achieved?

- Did the program result in positive outcomes for the clients?

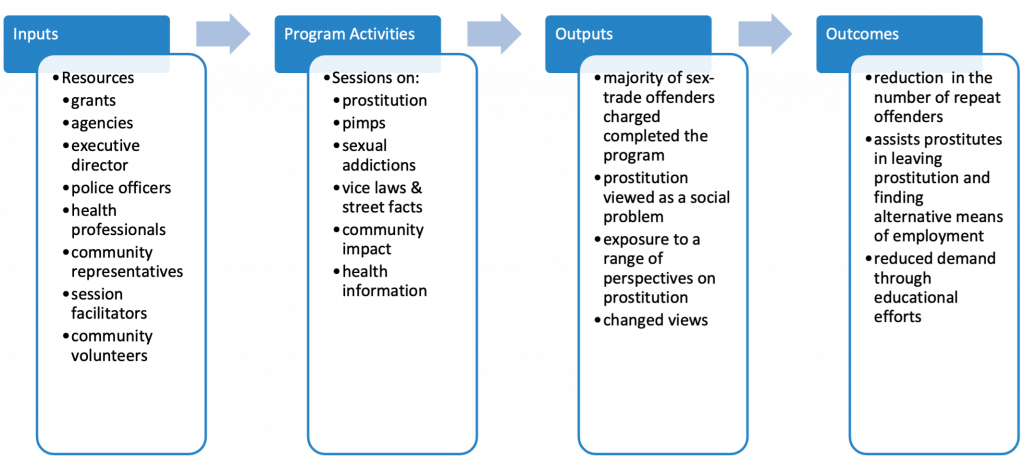

Program evaluations have historically relied on some form system’s model (see figure 11.5). The model describes the program by depicting its organizational structure in terms of interconnected inputs, including resources put into the program, such as funding, other agency involvement, and certified staff; activities, including program offerings, such as counselling sessions or skill development classes; outputs or results, including who attended the program; and outcomes, including the overall goals and benefits, such as reduced recidivism or increased social development. While this might come across as a straightforward approach to evaluation, it is anything but. Many programs are not amenable to evaluation because they do not have clearly articulated goals and objectives, or the goals and objectives are not realistic or measurable. Wholey (1994) suggests first employing an evaluability assessment to see if minimum criteria can be met before embarking on a full-scale evaluation of a program. An evaluability assessment includes (1) a description of the program’s overall model; (2) an assessment of how amenable that model is to evaluation, such as whether the goals and objectives are clearly stated and whether performance measures can be obtained; and (3) additional details on stakeholder views of the purpose and use of the evaluation findings, where possible (Rossi et al., 2019, p. 61). The purpose of the evaluability assessment is to gauge whether a program can be meaningfully evaluated. For example, programs designed to reduce the incidence of prostitution (i.e., the purchasing of sexual services), through educational efforts such as Sex-Trade Offender Programs (see Symbaluk & Jones, 1998), are regularly criticized for having unclear or unmeasurable goals. For example, how would it be possible to show that there was a reduced demand for prostitution? Yet this is a claim frequently made by proponents of these programs as evidence of their success (Coté, 2009). It is possible, however, to show a reduction in the number of complaints about street prostitution to the police by business and community members in a location, or to measure whether known prostitution offenders reoffend. Except, in both cases, this still is not evidence that the program was effective, because it could be that offenders are less likely to get caught a second time or that they learn to be more discreet, resulting in fewer complaints. An exemplary evaluability assessment template, an evaluation handbook, guidelines for selecting evaluators, and guidelines for an evaluation report can be downloaded from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (go to unodc.org and search for “Evaluability Assessment Template”).

Because programs are typically very costly to operate, questions concerning whether a program is effective sometimes translate into a cost-benefit analysis. A cost-benefit analysis is a method for systematically assessing the overall costs incurred by the program, including the ongoing costs needed to run the program such as wages paid to employees, rent for the building, and materials, versus outputs or program results, such as who benefited and how they benefited. Is the cost of the program justified, given the overall benefit to the clients or to the wider society? For example, the cost-benefit analysis of a sex-trade offender program might account for the financial costs of running the program for one year, including educational resources such as skilled facilitators, police personnel, and rental space for the classroom, in relation to the risk of the same number of men reoffending in the absence of the educational program. Or, a cost-benefit analysis might compare the financial costs and outcomes incurred by this program to other alternatives, such as criminal charges, fines, and vehicle seizures, to see whether the costs are warranted, given the benefits achieved. Sample questions include the following:

- How costly is this program (i.e., operating costs)?

- Are there ways to quantify the benefits of the program (e.g., into dollars saved)?

- How do various operating costs compare to alternative resources (e.g., wages)?

- How do the overall costs of the program compare to alternatives to the program?

- Are the costs of the program justified, given the overall benefits of the program?

- How do the costs and benefits of this program compare to alternate methods for dealing with the underlying social problem?

Carrying Out Evaluation Research

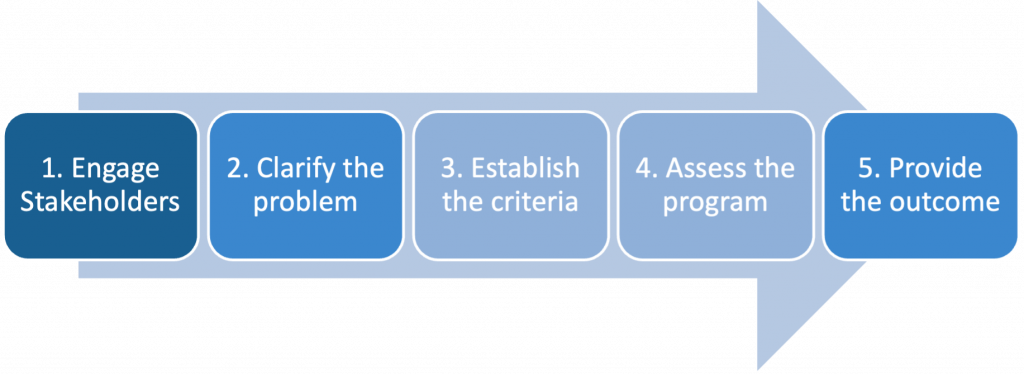

The process for carrying out evaluation research will vary depending on the type of evaluation, the exact program, and the evaluation objectives. However, an evaluation is generally going to proceed through these five stages as simplified here and depicted in figure 11.6:

- Engage with stakeholders who provide valuable input.

- Clarify the research problem—what question(s) are to be addressed in this evaluation?

- Establish evaluation criteria (the criteria the program is being evaluated against), including standards for indicating whether the program meets or fails to meet these criteria.

- Assess the program, including the selection of appropriate methods, data collection, and data analysis undertaken in order to measure performance against the established criteria.

- Provide the outcome, or the assessment or conclusion, reached in the evaluation.

Engaging with Stakeholders

Because a program is generally set up to provide a social service or resolve a particular social issue, a number of social relationships and roles exist within that program. For example, managers and other decision-makers supervise staff members who are responsible for delivering program services to intended target recipients. Social relationships involve stakeholders who need to be considered as part of the evaluation. Stakeholders include any individuals, groups, and/or organizations that are directly or indirectly involved with or impacted by the program of interest. For example, the target recipient of an intended service or intervention would be considered a primary stakeholder, as would employees involved in the operation of the program and groups that fund the program, such as program sponsors and donors. Stakeholders play a vital role in the creation, operation, and success of a program, and they are usually identified early on so that their input can be sought at various stages throughout an evaluation (Rossi et al., 2019).

For example, in an evaluation of a Canadian workplace-disability prevention intervention called Prevention and Early Active Return-to-work Safely (PEARS), Maiwald et al. (2011) sought feedback from three main groups of stakeholders: program designers, deliverers, and workers. The researchers used a variety of qualitative methods, including semi-structured interviews, participatory observations, and focus group sessions. Although the three groups of stakeholders defined the causes of workplace disability similarly, they placed emphasis on different aspects. For example, the deliverers explained disability largely in terms of risk factors and individual-level causes, while workers emphasized the importance of the workplace and organization contributors. In addition, while they agreed on the importance of workplace safety and the belief that workplace interventions can have a positive effect on work disability, stakeholders had very different ideas about how the intervention should work in practice. Deliverers, for example, largely targeted individual-directed measures, while workers felt these measures offered only short-term benefits, rather than a sustainable long-term return-to-work solution.

From this example, it becomes apparent that while all stakeholders have a vested interest in how a program or initiative operates, they are unlikely to view the program similarly. While different perspectives clearly help an evaluator gain a richer understanding, they also add to the complexity of the evaluation, as it becomes less clear which features should be changed and which ones should be retained. Guba and Lincoln (1994) suggest that one of the primary purposes of an evaluation is to facilitate negotiations among stakeholders so that they can come to a common or shared construction of the social program. In addition, Rossi et al. (2004) point out that “even those evaluators who do a superb job of working with stakeholders and incorporating their views and concerns in the evaluation plan should not expect to be acclaimed as heroes by all when the results are in. The multiplicity of stakeholder perspectives makes it likely that no matter how the results come out, someone will be unhappy” (p. 43). While a necessary and vital element in all program evaluations, stakeholders also constitute one of the main challenges in evaluation research.

Evaluator’s Role in Relation to Stakeholders

Evaluation research designs can be quite simple or highly complex, depending on the nature of the program and the objectives of the evaluation. At a minimum, the design should specify the questions the evaluator seeks to answer, the methods that will be employed to answer the questions, and the nature of the relationship between the evaluator and the stakeholders. An evaluator is likely to assume one of two main roles in an evaluation. Either the evaluator works directly with the stakeholders, who are part of the evaluation team with the evaluator acting as the team lead, or the program evaluator conducts research independent from the stakeholders but still consults with them at various points to establish the evaluation criteria and to obtain information used in the evaluation. In the case of the former, the research is often called participatory action research, collaborative research, or community-based research because the researcher is literally participating with the stakeholders to help them evaluate their own program. While there are some obvious disadvantages to this approach—as stakeholders, who are typically the greatest proponents of the program, are now in charge of evaluating it—there are also merits. People with a vested interest are also likely to be those willing to commit their time and resources to a process that they feel is useful and is likely to lead to welcomed improvements. Compare this to an approach in which (often) underpaid and overworked stakeholders are asked to commit additional time and resources on behalf of an outsider who is paid to assess their program and then tell them what their issues are (Stoecker, 2013).

A program evaluation most often takes the form of an independent evaluation. An independent evaluation is one led by a researcher who is not part of the organization and who has no vested interested in that organization. The evaluator is not a stakeholder but a commissioned researcher who designs the study, conducts the evaluation, and shares the findings with stakeholders (Rossi et al., 2019). Although the evaluator is not a stakeholder, they will still need to work closely with various stakeholders since stakeholders provide valuable data and inadvertently set the agenda for the program evaluation through their vested interests. For example, funding agencies are interested in cost-benefit analyses and outcome measures since they want to know if a program is run efficiently from a cost perspective and whether the program met its intended objectives. In contrast, program managers are more concerned with questions pertaining to program monitoring since their vested interest has to do with how the program operates. Finally, in some cases, programs are examined and evaluated to determine where changes can and should be made, as discussed in a later section on action. As a final comment on evaluation research, it is important to be aware of how evaluation research takes place within a larger political framework that ultimately influenced how that program came to be, why it is currently being evaluated, and what will happen once the assessment is made available.

Research on the Net

Canadian Evaluation Society

The Canadian Evaluation Society (CES) is a multidisciplinary association based on the advancement of evaluation theory and practice. The CES hosts an annual conference that serves as a forum for discussing current issues in evaluation. In addition, the CES and the Canadian Evaluation Society Educational Fund (CESEF) jointly host an annual Case Competition. In this student learning opportunity, teams compete for prizes and a trophy by first completing a preliminary round involving the analysis of a case file. Each team has six hours to complete their evaluation and submit it for judging. The highest-rated teams are invited to participate in the final round, held at the annual conference, where they receive a new case to evaluate and present their findings to a live audience.

Action Research

Action research, as its name implies, is a research strategy that attempts to better understand an area of interest in order to implement change within that area of interest. Greenwood and Levin (2007) define action research as “social research carried out by a team that encompasses a professional action researcher and the members of an organization, community, or network (‘stakeholders’) who are seeking to improve the participants’ situation” (p. 3). For example, action research is routinely employed in education, where it serves as a transformational methodology used to determine how to optimize learning strategies and programs so that they work best for students with a range of learning needs and skills. Multiple methods used to explore an issue can include interviews, focus groups, surveys, archival analysis, and the secondary analysis of existing data.

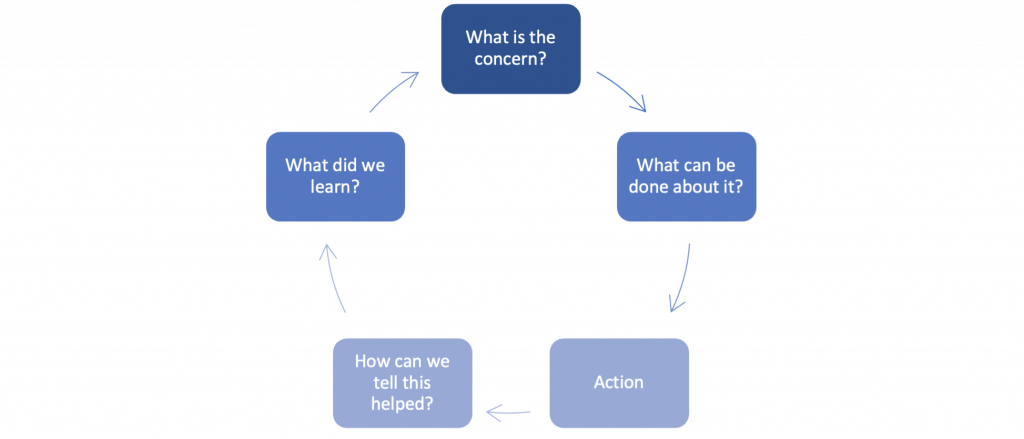

As a simplified illustration, a teacher might begin by identifying a problem or concern, such as students are having difficulty understanding an important concept, as evidenced by their grades on standard assessments as well as comments they have made in class. Once the problem is articulated via discussions with the class and in-depth interviews with a sample of students, the teacher needs to identify potential ways to resolve the issue. For example, other teachers might recommend strategies that have worked in their classrooms, there may be recommended strategies in the literature, and there may be potential solutions identified in the minutes from professional development meetings. After a period of reflection in which the teacher will consider potential options, they will then determine the course of action most suitable for this class and then implement it for a trial period. Following this, the teacher will need to evaluate the success of the strategy by reassessing students’ level of understanding on objective measures such as tests as well as through informal discussions with the students. Once the evaluation has occurred, the teacher can begin to consider how to change or modify future instruction based on what worked and did not work. See figure 11.7 for a summary of the logic underlying action research.

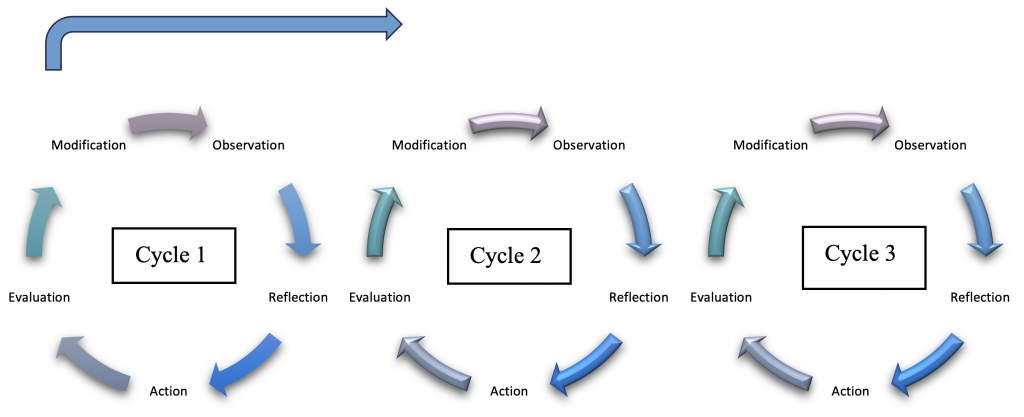

Action research is a continuous reflective, cyclical process that begins with observation, is followed by reflection, action, evaluation, modification, and then subsequent observation (McNiff, 2017). In this sense, action research generally involves a series of cycles as opposed to one phase of research. Going back to the earlier example, a teacher might try a learning strategy and then discover that is was only effective for certain students. In this case, another action cycle will begin. The second cycle will retain successes of the first phase and add in a new course of action to try to further improve upon the learning environment. For instructors who strive to continuously improve upon their teaching, the action cycle can continue indefinitely (see figure 11.8).

Source: Adapted from McNiff & Whitehead, 2006, pp. 9, 37.

The purpose of action research is not only to improve conditions, but to empower participants, since it is the stakeholders who participate directly in identifying the issues and means for resolving them. For this reason, action research is sometimes referred to as participatory action research. McKenzie et al. (1995) relied upon participatory action research to examine child welfare problems and practices in eight Manitoba First Nations communities. During the first phase of the study, focus groups and interviews were conducted with more than 200 individuals, including Elders, Chiefs, and Council members; biological parents, foster parents, and homemakers; local child and family service committee members as well as community staff members; and youth between the ages of 13 and 18. After common themes were identified in the responses provided, the researchers engaged in a second round of consultation in order to evaluate and validate the findings.

Consistent with the literature on Indigenous people, one of the common themes that emerged from this study was a traditional extended view of family that included aunts, uncles, cousins, and grandparents. In addition, along with concerns about the provision of good emotional and physical care and guidance, participants identified the common need to include the teaching of traditional values, language, and customs as part of the definition of what is in the “best interests of the child.” Another main finding was that in cases where there are indicators of inadequate care, support should be provided to that family such that potential solutions are enacted within the family setting (McKenzie et al., 1995).

Research on the Net

The Canadian Journal of Action Research

The Canadian Journal of Action Research is a free (“open access”) full-text journal dedicated to action research for educators. Here, instructors and administrators share articles, book reviews, and notes from the field.

Test Yourself

- What is case study research?

- For what reasons might a researcher choose a single-case study design over a multiple-case design?

- What is an independent evaluation?

- Why is it important to consult stakeholders in evaluation research?

- What is action research?

- What questions can be posed to depict the underlying logic of action research?

- What are the main steps in the process for carrying out an action research cycle?

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- Compare and contrast quantitative and qualitative approaches.

Quantitative approaches are based in the positivist paradigm and tend to be focused on objective methods that are based on deductive reasoning. Research questions are usually stated as hypotheses, and data collection is carried out in experiments, surveys, or certain forms of unobtrusive methods, such as the analysis of existing data. Quantitative methods are highly reliable but may be lacking in validity since findings from highly controlled experiments are difficult to generalize to the real world. Qualitative approaches, in contrast, tend to be based in the interpretive paradigm that emphasizes subjectivity and inductive reasoning. Research questions tend to be broad, and methods for data collection can include in-depth interviews, participant observations, and focus groups, as well as various forms of unobtrusive methods, such as content analysis. Qualitative methods tend to be higher in validity but lack reliability. - Define mixed-methods approach, explain why a researcher might opt for a mixed-methods design, and differentiate between mixed-method designs.

A mixed-methods approach always entails an explicit combination of qualitative and quantitative methods, as framed by the research objectives. Mixed methods can be useful for establishing the validity of measures and findings. For example, the results obtained in an experiment might be clarified by the results obtained via qualitative interviewing. In addition, mixed methods are useful for development purposes, such as when a researcher uses focus group findings to help inform categories that will later be used on a questionnaire. In a convergent design, both qualitative and quantitative methods are employed at the same time with equal priority. In an explanatory design, a quantitative method is employed first and then the findings are followed up on using a qualitative method. In an exploratory design, a qualitative method is prioritized and then, based on the findings from the qualitative study, the researcher develops and subsequently employs a quantitative method. - Define case study research and explain why a researcher might choose a single-case design over a multiple-case study.

Case study research is research on a small number of individuals or an organization carried out over an extended period. A researcher might opt for a single-case study if the case selected represents a critical case for testing a theory, if the case is common, if the case represents an extreme, if the case constitutes a rare opportunity, or if the researcher wishes to conduct a longitudinal analysis. - Define evaluation research and explain what an evaluation design entails.

Evaluation research is research undertaken to assess whether a program or policy is effective in reaching its desired goals and objectives. At a minimum, an evaluation design outlines the questions of interest, the methods for obtaining answers, and the nature of the relationship between researchers and stakeholders. - Define action research, describe the underlying logic of action research, and identify the steps in an action research cycle.

Action research is a research strategy that directly involves stakeholders to better understand an area of interest and to bring about improvement. The logic underlying action research centres on identifying a concern, determining what can be done about it, implementing an action, determining whether the action helped, and evaluating what was learned as a result. The process for carrying out action research entails observation, reflection, action, evaluation, and modification.

RESEARCH REFLECTION

- Suppose you are interested in studying one program that is specifically geared toward students at the school you are currently attending. As a case study, provide rationale for examining this program using a single-case design.

- If you were going to conduct an organizational case study of the school you are currently attending, describe two methods that you would use to collect suitable data.

- If you were going to conduct a Bachelor of Arts degree program evaluation, what three questions would you pose to help focus the evaluation? In other words, what three questions do you think should be answered in the evaluation?

- Thinking of the community in which you live, identify one main social issue that could be examined using participatory action research. Create a list of stakeholders you would include in a study designed to help address the social issue.

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE

Objective: To learn how to conduct case study research

Directions:

- Identify a local restaurant or coffee shop that you enjoy going to.

- Describe some of the features that lead you to enjoy this restaurant.

- Thinking of other restaurants or similar service providers, is this a typical case or more of an outlier? Explain your answer.

- Visit the restaurant and conduct an observation to see if there is anything else you wish to add to your description.

- Now suppose you have been asked by the owners to write a verifiable report on what makes this restaurant enjoyable.

- How could you go about proving your claims?

- How could you find out if others share similar views?

- List and describe three methods you could use to help substantiate your description of what makes this restaurant special.

- Based on the methods you selected and the potential order in which you could employ these methods, would your resulting design be best described as a mixed-methods design or a design that includes the use of multiple methods?

RESEARCH RESOURCES

- For information on more advanced mixed-methods designs, see Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2023). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches (6th ed.). Sage.

- To learn more about designing case study research, refer to Hancock, D. R., Algozzine, B., & Lim, J. H. (2021). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers (4th ed.). Teachers College Press.

- For a peer-reviewed interdisciplinary, international journal on the theory and practice of action research, see Sage’s Action Research.

- To learn whether the benefits outweighed the costs of Canada’s vaccination program for Covid-19, see Tuite, A. R. et al. (2023). Quantifying the economic gains associated with Covid-19 vaccination in the Canadian population: A cost-benefit analysis. Canada Communicable Disease Report, 49(6), 263–273.

A research design that includes an explicit combination of qualitative and quantitative methods as framed by the research objectives.

A mixed-method design in which qualitative and quantitative methods are employed concurrently, with independent data collection and analysis compared in the final interpretation.

A mixed-method design which a quantitative method is employed first and then the findings are followed up on using a qualitative method.

A mixed-method design in which a qualitative method is employed first and then the findings are used to help develop a subsequent quantitative-method–based phase.

A case study strategy that focuses on only one person, organization, event, or program as the unit of analysis, as emphasized by the research objectives.

A case study strategy that focuses on two or more persons, organizations, events, or programs selected for the explicit purpose of comparison.

A systematic evaluation focused on improving an existing condition through the identification of a problem and a means for addressing it.

A systematic method for collecting and analyzing information used to answer questions about a program of interest.

A method for assessing the overall costs incurred by a program relative to outcome measures.

An individual, group, or organization that is directly or indirectly involved with or impacted by the program of interest.

An evaluation that is headed up by a researcher who is not a primary stakeholder for the program under consideration.

Social research carried out by a team that encompasses a professional action researcher and the members of an organization, community, or network (stakeholders) who are seeking to improve the participants’ situation.