Chapter 3: Research Ethics

Many research textbooks explain research methods and their ethical aspects as logical processes that follow a given number of steps. Research, however, does not take place in a vacuum. It is imagined, designed, planned, funded (or not), executed, and reported in a complex world by and with people with a whole range of viewpoints, values, needs, beliefs, and agendas.

— Martin Johnson, 2007, p. 29

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

- Define research ethics and provide examples of research-related ethical conduct.

- Recognize links between early military research and regulatory outcomes.

- Discuss ethical considerations raised by classic studies in social research.

- Discuss the potential for harm, risk-benefit analysis, informed consent, privacy and confidentiality, and debriefing as major ethical considerations in social science research.

- Identify the core principles of the Tri-Council Policy Statement TCPS 2 (Canadian Institutes of Health Research [CIHR] et al., 2022).

- Describe the role of an ethics review board and outline the process for undergoing an ethical review of research.

INTRODUCTION

From medical breakthroughs to technological innovations to discoveries in the social sciences, few would argue against the importance of including humans in research. Along with the need to involve humans in research is a corresponding ethical obligation on the part of physicians and researchers to treat participants in a safe, dignified, and well-informed manner. Ethics refer to “conduct that is considered ‘morally right’ or ‘morally wrong’ as specified by codified and culturally ingrained principles, constraints, rules, and guidelines” (Rosnow & Rosenthal, 2013, p. 41). Professionals in society are expected to adhere to ethics guiding their occupations. For example, physicians, residents, and medical students uphold the Canadian Medical Association’s Code of Ethics and Professionalism, which consists of a number of virtues such as “trust” and “compassion,” commitments including the “commitment to the well-being of the patient,” and professional responsibilities (Canadian Medical Association, 2018). Similarly, all members of the Canadian Psychological Association, whether they are practitioners or not, are bound by the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists (Canadian Psychological Association, 2017), just as members of the Canadian Sociological Association are guided by the Statement of Professional Ethics (Canadian Sociological Association, 2022).

Research ethics refer to an array of considerations that arise in relation to the morally responsible treatment of humans in research, including means for protecting the welfare and dignity of participants and procedures for assessing the overall risks and benefits. For example, where possible, researchers carefully explain the procedures, risks, and benefits of a study to potential participants prior to their participation in the study. Researchers also obtain informed consent from participants prior to their enlistment in a study, they make participants aware that their participation is voluntary, and they make sure participants understand that they are free to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Ethical conduct also includes designing research procedures in a manner that minimizes the potential for causing harm and maintains the privacy of individual participants. However, as implied by the opening quote, while ethical principles and procedures may appear straightforward from a moral perspective, researchers are people with divergent interests, agendas, and even flaws. They may intentionally or inadvertently place participants in situations that they are ill-informed about ahead of time, that inflict harm, that invade privacy, or that otherwise compromise human dignity.

This chapter examines historical and social science cases involving the unethical treatment of humans in research, along with the development of principles and procedures used to help guide ethical human-based research. In later chapters, you will see how particular research techniques may pose special ethical dilemmas for researchers, such as when researchers try to balance the trust established with participants against the research objectives in field studies where a researcher joins a group to study it (see chapter 10).

UNETHICAL TREATMENT OF HUMANS AND REGULATORY OUTCOMES

Numerous military and medical cases involve the unethical treatment of unsuspecting citizens, soldiers, prisoners of war, and various vulnerable populations. These studies provide a historical context for understanding the ethical principles that regulate and govern research involving humans today.

Military Research: Nazi Experiments 1939–1945

Medical experimentation on human prisoners was routinely conducted during World War II. German physicians, military officials, and researchers subjected men, women, and children from concentration and death camps to all sorts of torturous treatments to learn how to carry out medical practices, to find out more about the course of disease pathology, to test the limits of human suffering, and even to establish means for eliminating the Jewish race.

Famous examples include Professor Carl Clauberg, who developed a technique for the mass non-surgical sterilization of Jewish women using chemical irritants; SS-Sturmbannführer Horst Schumann, who induced sterilization by subjecting women’s ovaries and men’s testicles to repeated radiation via X-rays; Chief SS physician Dr. Eduard Wirths, who studied contagious diseases by first inflicting them upon prisoners (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2024); and Dr. Josef Mengele (the “Angel of Death”), whose interest in genetic abnormalities led him to carry out often-fatal surgical procedures on sets of twin children, including the removal and exchange of internal organs and tissues (Lagnado & Dekel, 1991). Experiments were also routinely conducted to inform the German army about health issues, to help the government advance anti-Semitism plans involving racism and hatred toward people of Jewish descent, and to aid academics and physicians in furthering their own personal or professional agendas (Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2024).

The Nuremberg Code

Many of the physicians, political leaders, and researchers implicated in the inhumane studies discussed above were prosecuted for their actions in a series of military tribunals. The Nuremberg trials, which commenced in 1945 at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, Bavaria, in Germany, defined the Nazi medical experiments as “war crimes” and “crimes against humanity” and resulted in lengthy prison and/or death sentences for guilty defendants. Another important outcome was the establishment of a set of 10 directives for human experimentation called the Nuremberg Code. The Nuremberg Code (1949) is among the first published set of ethical guidelines, as summarized in the excerpts below:

- The voluntary consent of the human subject is absolutely essential.

- The experiment should be such as to yield fruitful results for the good of society.

- The experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation.

- The experiment should be so conducted as to avoid all unnecessary physical and mental suffering and injury.

- No experiment should be conducted where there is an a priori reason to believe that death or disabling injury will occur.

- The degree of risk to be taken should never exceed that determined by the humanitarian importance of the problem to be solved by the experiment.

- Proper preparations should be made and adequate facilities provided to protect the experimental subject against even remote possibilities of injury, disability, or death.

- The experiment should be conducted only by scientifically qualified persons.

- During the course of the experiment the human subject should be at liberty to bring the experiment to an end.

- During the course of the experiment the scientist in charge must be prepared to terminate the experiment at any stage. (pp. 181–182).

Research on the Net

Canadian War Veterans Exposed to Mustard Gas

Military experimentation extends beyond Germany and prisoners of war to include Canadian soldiers who volunteered for studies designed to help military warfare. Many participants kept oaths of secrecy despite long-standing suffering, and even eventual death in some cases, from related health implications. In May 2004, the Canadian government released a $24,000 compensation payment to retired Master Corporal Roy Wheeler and retired Flight Sergeant Bill Tanner (CBC News, 2004). The two soldiers were the first of about 2,500 remaining World War II veterans to receive an official apology and reparation on behalf of an estimated 3,500 men exposed to mustard gas and other deadly chemicals. Experiments on the effects of chemical warfare agents were conducted by the Canadian military at Canadian Forces Base Suffield near Medicine Hat in Alberta for a 30-year period from 1940 to 1970 (CBC News, 2004). While the compensation acknowledges unethical treatment, it cannot repair health implications suffered by the soldiers, including infertility, heart disease, and lung complications. Learn more by going to the CBC News Online article, “Canadian war vets exposed to mustard gas receive compensation.”

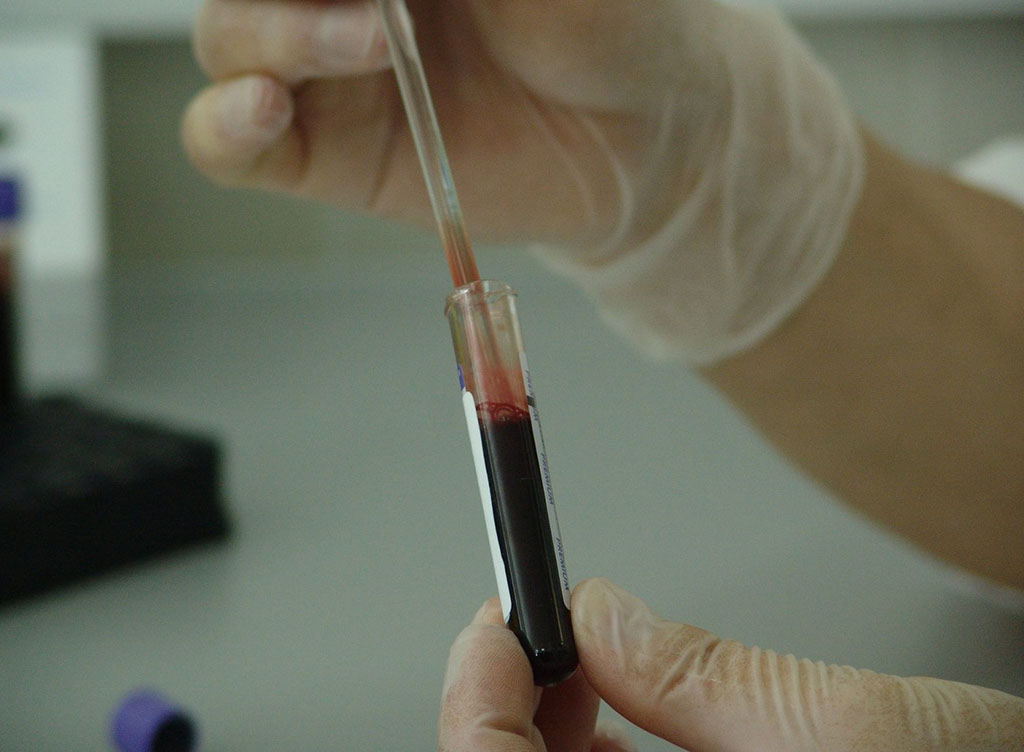

Biomedical Research: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The unethical treatment of patients is not limited to prisoners of war and military personnel. In 1932, 600 low-income African American men from Macon County, Alabama, were recruited by the United States Public Health Service for a study on the natural (i.e., untreated) progression of the sexually transmitted disease syphilis (Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee, 1996). Although 399 of the men had syphilis at the onset of the study, they were never informed about their condition. Instead, the men were told they were being examined for “bad blood.” They were monitored over a period of almost 40 years, during which they were not given the standard therapy for syphilis of the time nor the penicillin that was developed as a cure in 1947. Researchers even persuaded local doctors to withhold standard antibiotics (Stryker, 1997). In exchange for their willingness to participate, the men were provided with free meals, free medical examinations, and free burials (Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee, 1996). Note that the study continued long after the establishment of the Nuremberg Code. In fact, the research went on for four decades, until lawyer Peter Buxton took the case to the media. The Tuskegee study came to an end in 1972, when Jean Heller of the Associated Press released the story, making the true purpose of the research apparent (Stryker, 1997).

An obvious implication of the withholding of knowledge of the disease in conjunction with the prevention of treatment was that the men suffered prolonged physical symptoms and many eventually died, passed the disease on to their wives, and even, in some cases, passed it on to their children as congenital syphilis. Survivors and their families eventually received financial compensation resulting from a class action suit. On May 16, 1997, then President Bill Clinton formally apologized on behalf of the government to the remaining survivors, their families, and the community for wrongdoings carried out at Tuskegee (Tuskegee University, 2024).

The Belmont Report

In response to the Tuskegee study, the United States Congress passed the National Research Act in 1974, which created the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Since medical practices and research often occur together, the Commission outlined boundaries between medical practices and research to help determine conditions under which the actions of physicians and researchers would require review (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research [NCPHSBBR], 1979). A summary of the recommendations by the Commission, called the Belmont Report, outlines three basic ethical principles meant to guide all future research involving humans:

- Principle 1: Respect for persons

- Principle 2: Beneficence

- Principle 3: Justice

Respect for persons is a moral principle stressing the importance of people being treated as “autonomous agents.” This means all participants should be valued as individuals who are free to make choices for themselves, including whether they wish to participate in a study. Beneficence is a term that is used to describe the general personal safety and well-being of research participants. Beneficence as a moral principle refers to the dual notions of (1) “do no harm” and (2) “maximize possible benefits and minimize potential harms” (NCPHSBBR, 1979). Justice is a moral principle based on “fairness” attributed to common-sense adages such as “to each person an equal share” and “to each person according to individual need.” In this case, it is expected that researchers will make decisions and behave in socially responsible ways. For example, “an injustice occurs when some benefit to which a person is entitled is denied without good reason or when some burden is imposed unduly” (NCPHSBBR, 1979, p. 5).

Recruiting the Poor for Clinical Drug Trials

Unfortunately, the principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice are not always upheld, as evidenced by the ongoing exploitation of disadvantaged groups for the advancement of science and profits. On March 4, 2012, Dateline NBC correspondent Chris Hansen reported on the exploitation of poor people living in Ahmedabad, India, by U.S. pharmaceutical companies who pay participants to undergo clinical trials. Some of the test subjects were recruited by Rajesh Nadia, who was also paid for every person he found on behalf of the drug companies. In his interview with Chris Hansen, Nadia admitted the recruits often disregard the potential health risks and sometimes even enlist in overlapping studies for financial incentives (Sandler, 2012). How can pharmaceutical companies get away with this? Satinath Sarangi, director of the Bhopal Group for Information and Action, noted that “you can do it cheaply, do it with no regulation, and even if there are violations, get away with it” (Sandler, 2012). India is one of many countries targeted by pharmaceutical companies. As another example, view the Journeyman Pictures 2016 production “Big Pharma Companies are Exploiting the World’s Poor” on YouTube to learn more about clinical trials involving children and infants in Argentina.

Test Yourself

- What do research ethics refer to?

- What features of the Tuskegee study illustrate unethical biomedical research?

- What three ethical principles are highlighted in the Belmont Report?

UNETHICAL TREATMENT OF PARTICIPANTS IN SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH

In what proved to be among the most controversial set of studies ever conducted in the social sciences, Yale University Professor Stanley Milgram (1961) devised a procedure, while still in graduate studies, for examining obedience. In this study, a naive participant followed orders to administer increasingly painful electric shocks to a fellow participant serving as the “learner.” In one of the earliest versions of what turned out to be a series of experiments, Milgram (1963) recruited participants through a newspaper advertisement for a paid study on memory conducted at Yale University. When a participant arrived at the university, he was greeted by an experimenter and an accomplice posing as the other participant in a two-person study of the effects of punishment on learning. After a brief overview, participants were asked to draw slips of paper from a hat to determine who would assume the role of the “teacher” and who would become the learner. The draw was fixed so that both slips of paper said “Teacher,” ensuring that that the participant would always end up in the role of the teacher, while the accomplice would assume the role of the learner.

The participant and accomplice were then taken to adjacent rooms and the learner was hooked up to a shock-generating apparatus, making it apparent to the teacher that the victim would be unable to depart the experiment of his own accord. The apparatus consisted of a series of lever switches marked in increments of 15 and labelled with descriptors to indicate increasing voltage from 15 (slight), to 75 (moderate), to 135 (strong), to 195 (very strong), to 255 (intense), to 315 (extreme intensity), to 375 (Danger: Severe Shock), up to 420, where the descriptor was Xs. To add credibility, the teacher was then given a sample shock of 45 volts (Milgram, 1963).

Throughout the experimental task, the teacher was instructed to give a shock by pressing down a lever on the shock generator each time the learner provided an incorrect answer. Importantly, the teacher was also told to increase the shock level after each error and call out the value, such that the voltage increased by 15 and the voltage amount was salient to the teacher. At pre-planned intervals, according to a script, the victim (learner) protested the shock treatment using various forms of feedback, such as pounding on the wall and screaming out in pain, until the shock value of 300 volts was reached. After that, the learner no longer responded. If, at any point during the experiment, the teacher stopped giving shocks and/or sought guidance on how to proceed, the experimenter followed a sequence of scripted prods, including “Please continue” or “Please go on,” “The experiment requires that you continue,” “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” and “You have no other choice, you must go on” (Milgram, 1963, p. 374).

Results indicated that participants believed they were administering real shocks, and they showed signs of extreme tension (e.g., sweating, stutter, trembling). Of the 40 participants included in the original version, the first refusal to continue came at 300 volts, with five subjects terminating their participation. An additional four quit at 315 volts, two more stopped at 330 volts, and one more left the study at each level of 345, 360, and 375 volts, for a total of 14 who defied the experimenter and 26 who obeyed orders to the very end (Milgram, 1963).

This procedure was replicated by Milgram in more than 20 variations, including conducting the experiment in different countries (e.g., Norway and France), introducing group dynamics (e.g., the teacher was part of a small group obeying or breaking off from the orders of the experimenter), introducing varied elements of the assumed responsibility (e.g., the learner made it evident he did not wish to continue but was unable to get out of the study without help; the experimenter claimed full responsibility for the situation), and changing the salience or immediacy of victim (e.g., the victim was placed within view of the teacher) (Russell, 2010). In most cases, large numbers of participants obeyed the experimenter, providing what would be severely painful shocks to an innocent victim (i.e., the learner), and completing the study to the end. The fact that about two-thirds of the participants obeyed orders to the end goes against what we might consider to be common sense, which tells us that only in rare cases involving a highly sadistic or evil sort of person should this happen. Zimbardo (2004) explains that even 40 psychiatrists who were given a description of Milgram’s procedures ahead of time failed to account for situational determinants and predicted that fewer than 1 percent of participants would shock to the maximum of 450 volts.

Milgram’s experiments were widely criticized for their use of deception that evoked prolonged periods of distress where participants believed they were harming another individual. Milgram (1963) reported that “in a large number of cases the degree of tension reached extremes that are rarely seen in sociopsychological laboratory studies. Subjects were observed to sweat, tremble, stutter, bite their lips, groan, and dig their fingernails into their flesh. These were characteristic rather than exceptional responses to the experiment” (p. 375). Milgram (1963) went on to say that “one sign of tension was the regular occurrence of nervous laughing fits. Fourteen of the 40 subjects showed definite signs of nervous laughter and smiling. The laughter seemed entirely out of place, even bizarre. Full-blown, uncontrollable seizures were observed for three subjects. On one occasion we observed a seizure so violently convulsive that it was necessary to call a halt to the experiment” (p. 375). Many readers are left wondering if the “friendly reconciliation” between the learner and teacher that Milgram arranged at the end of the study was enough to disengage the tension produced throughout the study. As Diana Baumrind (1964) noted in an article questioning the ethics of Milgram’s research,

[i]t would be interesting to know what sort of procedures could dissipate the type of emotional disturbance just described. In view of the effects on subjects, traumatic to a degree which Milgram himself considers nearly unprecedented in sociopsychological experiments, his casual assurance that these tensions were dissipated before the subject left the laboratory is unconvincing. (p. 422)

Baumrind (1964) further points out that Milgram has no way of determining how this study might negatively impact on the self-image of participants or their future views of authority figures.

In addition to the potential for lasting distress suffered by participants, the very topic of Milgram’s studies (i.e., obedience) warranted a type of procedure that necessarily impinged on the voluntary nature of participation. That is, teachers were ordered to continue and told they must go on even when they said they wished to stop. This practice clearly goes against voluntary participation since the teachers were not free to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

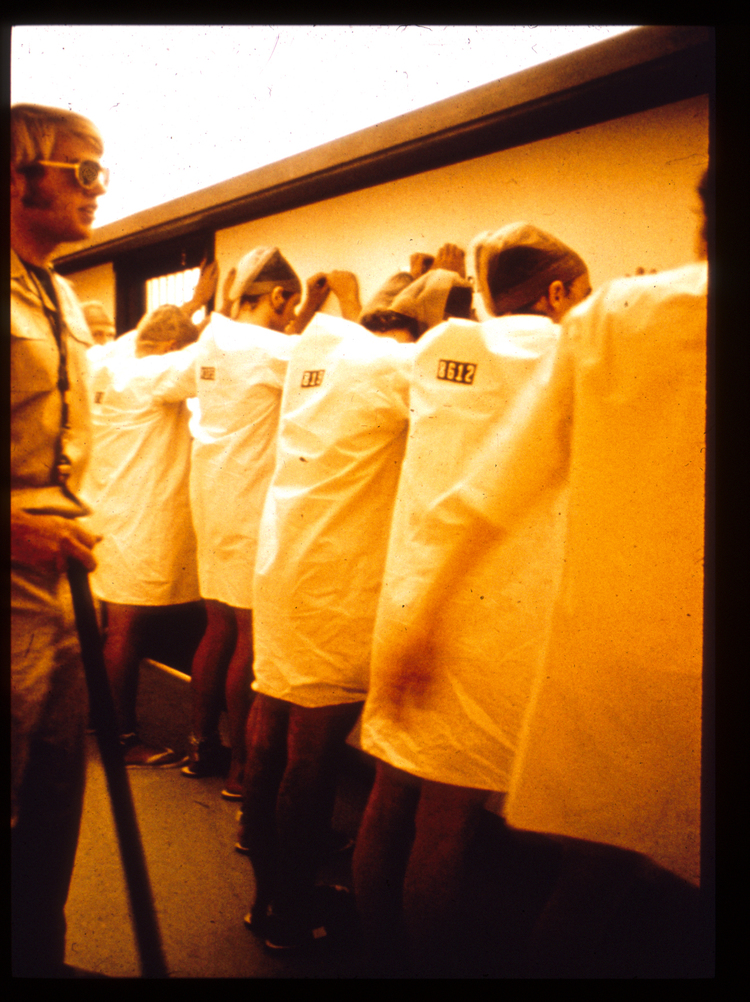

Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment

To study the interpersonal nature of prison life, Philip Zimbardo, Craig Haney, and Curtis Banks set out in 1971 to design a simulated prison in which participants would be randomly assigned to the role of “prisoner” or “guard” (Haney et al., 1973). The procedures for this study were relatively straightforward. Participants were recruited through a newspaper advertisement seeking paid volunteers for a “psychological study of prison life.” Of the 75 respondents, 21 were selected, based on extensive background screening to determine those with the most “stable,” most “mature,” and least “anti-social” tendencies. Participants were informed that they would be assigned to either a guard or prisoner role and that they would be paid $15 per day for a period of up to two weeks. They signed a contract “guaranteeing a minimally adequate diet, clothing, housing, and medical care, as well as the financial remuneration in return for their stated “intention” of serving in the assigned role for the duration of the study” (p. 74). No instructions were given for how to carry out a prisoner role, although they were forewarned that they would have little privacy and they could expect to have their “basic civil rights suspended during their imprisonment, excluding physical abuse” (p. 74). Those serving as guards were given vague instructions to “maintain the reasonable degree of order within a prison necessary for its effective functioning” (p. 74).

With assistance from the Palo Alto City Police Department, participants assigned to the prisoner role were unexpectedly arrested at their homes and taken to the mock prison to begin the study, which took place in the basement of the psychology building at Stanford University. When the prisoners arrived, they were “stripped, sprayed with a delousing preparation (a deodorant spray) and made to stand alone naked for a while in the cell yard” (Haney et al., 1973, p. 76). Following this, they were issued a uniform, had their ID picture taken, were taken to a cell, and were “ordered to remain silent.” As part of the administrative routine, the warden, played by an undergraduate assistant, then explained rules for prisoners that the guards and the warden had created. These rules included being referred to as only a number, the granting of minimal supervised toilet breaks and limited scheduled visits, and complying with regular “count” lineups, among other things.

Results showed that, over time, guards became increasingly negative, aggressive, and dehumanizing, while prisoners became increasingly passive and distressed. Haney et al. (1973) noted that “extremely pathological reactions which emerged in both groups of subjects testify to the power of the social forces operating” (p. 81) and “the most dramatic evidence of the impact of the situation is seen in the gross reactions of five prisoners who had to be released because of extreme emotional depression, crying, rage, and acute anxiety” (p. 81). Anyone who has seen video footage from the study is likely to question why the study was not stopped sooner or why particular prisoners who showed signs of extreme distress and begged to be let out of the study were not immediately allowed to do so. Even Zimbardo admits that it should have been his “job to hold in check the growing violence and arbitrary displays of power of the guards rather than to be the Milgramesque authority who, in being transformed from just to unjust as the learner’s suffering intensified, demanded ever more extreme reactions from the participants” (Zimbardo et al., 2000, p. 194). It was not until after his soon-to-be-wife’s tearful admonishment, “What you are doing to those boys is a terrible thing!” (p. 216) followed by a heated argument, that Zimbardo detached from his role as the prison superintendent and more fully appreciated how the power of the situation had taken over those in it, including himself (Zimbardo et al., 2000). For more information on the prison study, along with lectures, articles, and media interviews related to the study, as well as recent criticisms and responses, please refer to the official website for the Stanford Prison Experiment.

Activity: Unethical Treatment of Humans

Test Yourself

- What features of Milgram’s study posed ethical concerns?

- What features of Zimbardo’s study posed ethical concerns?

ETHICAL ISSUES COMMON TO SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH

The historical medical, military, and social science examples discussed thus far all help to illustrate key ethical issues that arise in research. Five recurring concerns are discussed in more detail in this section, including the potential for harm, risk-benefit analysis, informed consent, privacy and confidentiality, and debriefing. These issues are still prevalent today and they need to be specifically addressed by researchers who plan to apply for ethical approval for research involving humans as participants.

1. The Potential for Harm

Perhaps the most essential consideration in any study is its potential to produce harmful outcomes for participants. Any procedure that requires participants to engage in physical activity has the potential, even if slight, for someone to incur an injury. Similarly, a clinical drug trial might require participants to ingest a medicine that could produce physical side effects such as sweating, blurred vision, or an increased heart rate. In most cases where there is the potential for physical harm, researchers attempt to design their study in a manner that minimizes the risk. For example, in research on factors influencing participants’ willingness to endure the pain of an isometric sitting exercise, we included only physically active, healthy individuals aged 18 to 25 who were continuously monitored and whose heart rates were assessed every 20 seconds to ensure their ability to continue safely to a maximum of six minutes (Symbaluk et al., 1997). Harmful studies such as those conducted by the Nazi doctors or the researchers in the Tuskegee syphilis study would never receive ethical approval today.

It is also possible for participants to experience psychological forms of harm, as in the case of the severe stress experienced by some of the subjects in Milgram’s experiments, who believed they were giving painful electric shocks to an innocent victim, or the “prisoners” in Zimbardo’s experiment, who were verbally abused and degraded by the “guards.” Participants may also experience stress as a function of being asked personal questions during an interview or disclosing private information on a questionnaire. In addition, being provided with certain kinds of feedback during a study, as happens when a participant determines they are performing extremely poorly relative to the other participants on a task, can lead to feelings of stress. In cases where procedures have the potential to evoke high levels of stress (e.g., the roles of prisoners and guards), safeguards need to be built into the study, such as careful monitoring, the ability to readily terminate a study, and ways to assess the stress. Where stressful reactions become apparent, especially if they were unanticipated ahead of time (e.g., as a function of a question being asked during an interview), the onus is on the researcher to respond in a timely and appropriate manner.

Harm can take even less obvious forms that may not be apparent prior to the onset of a study. For example, researchers may obtain approval from participants to include visual forms of data in their research projects—such as photographs, works of art, or films that represent participants, their perspectives, or cultural practices and ceremonies—that prove to be harmful to individuals or communities once the images are disseminated in the public domain. For example, imagine how you would feel if you consented to having your photo taken for a research project on cellphone use and then it was included alongside negative findings on distracted driving practices? Marcus Banks and David Zeitlyn (2015) recount issues with an early ethnographic study on a tribe in northeastern Uganda carried out by Colin Turnbull (see Turnbull, 1973) where the researcher included photographs of individuals making hunting weapons in what had recently become a national park. While a researcher’s intent may be to portray a group or a practice using photographs to capture the authenticity of the research, there may be a host of unanticipated consequences for the now identified individuals. Banks and Zeitlyn (2015) suggest it is not so much a question of whether researchers should have the right to visually represent others but more a case of “how and under what conditions do they negotiate that right with those who are represented?” (p. 123). Visual representation is discussed in more detail under Privacy and Confidentiality.

2. Risk-Benefit Analysis

Studies should be designed to minimize harm and maximize benefits. Through risk-benefit analysis, studies that necessitate the use of known harm but contribute little to our understanding are usually considered unethical, while studies that minimize the potential for harm or result in negligible harm but greatly improve programs, help to reduce suffering, or have widely applicable benefits are more apt to be deemed ethical.

While Milgram’s experiments clearly caused harm, they must be evaluated in historical context. These studies were the only ones to examine obedience at a time when science had yet to explain how millions of innocent people had lost their lives at the hands of otherwise “ordinary” Nazi soldiers and officials, many of whom claimed they were simply following orders. Similarly, while participants in Zimbardo’s study were also negatively affected by their experience, the researchers could not anticipate the severity of the situation or how they themselves would be carried away by situational forces. In both cases, the importance of the findings for teaching us about obedience and situational forces, as well as how to build in participant safeguards in subsequent research, cannot be understated. While much of the information presented above is in hindsight, the point is that all research has benefits and drawbacks that need to be carefully weighed out to determine the merit of any given study at a point and place in time.

3. Informed Consent

Under no circumstances should people be coerced, misled, or otherwise forced to take part in research. The indictment of the physicians implicated in Nazi medical experiments during the Nuremberg trials was less based on the harm incurred than the fact that victims were forced into the experiments against their will. Informed consent refers to a process where potential participants are provided with all relevant details of a study needed to make a knowledgeable judgment about whether to participate in it.

Informed consent is usually obtained with a written consent form that discloses all relevant details of the study and clearly establishes the voluntary nature of participation. The form contains a statement indicating that the study constitutes research; a description of the nature and purpose of the research; an outline of the procedures, including the anticipated timelines; a disclosure of any potential risks and benefits; alternatives to participation; measures taken to ensure privacy, anonymity, and confidentiality; details of any reimbursement or compensation for participating; assurances that participation is voluntary; and contact information for the researchers.

Note that various factors can challenge the process for obtaining informed consent. For example, participants with limited or impaired cognitive ability may lack the capacity to understand the risks and benefits of a study or what is required in the role of a participant. Similarly, consent cannot be obtained from children without both their approval and the approval of adults who are responsible for them. Finally, individuals in vulnerable positions, such as persons who are serving time in prison or employees being asked to take part in a study by their employers, may be informed that participation is voluntary, but they still may believe that a failure to participate could have negative repercussions.

According to Cozby et al. (2020) informed consent should be obtained in a manner that is readily understood by the public and aimed at an education level of about grade six to eight. In addition, the form should be written as an informal letter to the participant as opposed to a legal document. The letter should be free of any kind of technical terms specific to a research area or discipline. Finally, it should be apparent to the potential participant that they are free to withdraw consent at any time, without penalty. Importantly, signing a consent form is not the same thing as signing a waiver form, where a person absolves all others of blame. A researcher remains responsible and may incur later legal liability for actions taken or not taken during a study that result in harm to the participant. For more information on what to include in a consent form, refer to the detailed template on the Human Ethics website at MacEwan University found in the section “Consult Ethics Handbook and consent templates.”

4. Privacy and Confidentiality

Another key ethical issue in research concerns the loss of privacy and confidentiality. Although researchers try to uphold the privacy of participants, in many instances social research itself necessitates an invasion of privacy. From the completion of a relatively harmless online survey that intrudes into a respondent’s personal time to highly personal questions about one’s private experiences asked by a qualitative researcher in a face-to-face interview, research spans a continuum when it comes to loss of privacy. Sometimes a researcher may be more interested in the responses than in the respondents in a given study. In such cases, researchers may be able to maintain the anonymity of participants by keeping their names off any of the documentation that contain responses. Anonymity exists if a researcher cannot link any individual response to the person who provided it. As an example, consider student evaluations of courses and instructors, where student responses are anonymous because students do not include their names or any other identifying information on the evaluation instruments.

Confidentiality is an ethical principle referring to the process enacted to uphold privacy (Sieber, 1992). For example, a researcher may be able to identify a person with their responses if an interviewer can clearly see who is providing the responses; however, the researcher promises not to later disclose information that would identify that person publicly. Confidentiality can often be upheld by reporting collected data in an aggregate (i.e., grouped) rather than individual format. In other cases, information may need to be omitted to preserve privacy. For example, a published report that indicated that a participant held a position as mayor or was a director of human resources at a university would inadvertently reveal the identity of that participant. Researchers routinely use pseudonyms in place of actual names, and they may even change a few details, such as the sex or age of a participant, to respect privacy.

Finally, in some forms of research it may not be possible to guarantee anonymity or confidentiality. For example, in focus groups (discussed in more detail in chapter 9), participants who are introduced to one another may later disclose identifying details from a research session, irrespective of researcher intentions. As another example, in visual research, photographs that become part of the research data and process may depict a participant’s identity, or they may depict the identity of other individuals who were not part of the research project, as in the case of a participant’s photo collection, which might include photos of family members and friends, photos that depict events involving groups of people, and even historical photos of now deceased individuals. The originator of Marion and Crowder (2013) identify seven key ethical issues raised in visual research, including

(1) “representational authority,” concerning who gets to decide how the image is depicted, in terms of the perspective created; (2) “decontextualization/circulation,” concerning where the image ends up and how it gets used; (3) “presumed versus actual outcomes of image display”; (4) “relations with and responsibilities toward research subjects/communities”; (5) “balancing privacy versus publicity, depending on subject’s wishes”; (6) “the importance of communication and consent of subjects and communities at every stage of the research process”; and (7) the collection and dissemination of visual materials within the context of globally expanding media savvy and presence. (pp. 6–7)

Research in Action

Canadian Researchers Take Confidentiality to Court

Confidentiality was first put to the test in early 1994 in a Canadian case in which a researcher was subpoenaed to appear in court to provide evidence that would identify research participants (Palys & Atchison, 2014). The researcher was Russel Ogden, a then–MA student in the School of Criminology at Simon Fraser University who was carrying out controversial research on assisted suicide among individuals suffering from HIV/AIDs. Ogden guaranteed his research participants “absolute confidentiality” and therefore refused to provide any identifying information, on ethical grounds. Although he was threatened with a charge of contempt of court, he eventually won his case. The riveting case, the legal and ethical implications, and the controversy involving Simon Fraser University for its initial lack of support are described by Palys and Atchison (2014) and are outlined in detail in a webpage posted by Ted Palys called Russel Ogden v. SFU.

More recently in 2016, Dr. Marie-Ève Maillé was subpoenaed to turn over confidential interview-based material stemming from her dissertation research into conflict among residents concerning the building of a wind farm. However, the Superior Court of Quebec reversed this decision in 2017 upholding the importance of confidentiality in research involving humans as participants (Castonguay, 2017).

5. Debriefing

Debriefing refers to the full disclosure and exchange of information that takes place upon completion of a study. Debriefing is required in most situations where participants are not provided with all of the details of the study or are misled about details of the study prior to participating in it. In social psychological research, for example, deception is sometimes required to maintain the integrity of the main variable under consideration. For example, suppose you wish to conduct an experiment on helping and want to see how many students are willing to help classmates who request to borrow notes under the pretense of missing class due to an illness. If you informed participants ahead of time that someone was going to approach them at the end of class and ask to borrow notes, so you could measure whether they helped, this knowledge would likely affect their willingness to help, in a manner that would negate the purpose of the study. Note that deception or the misleading of participants in social psychological research either by misconstruing or omitting details is different than the concealment of a researcher’s identity or research purpose within a covert role sometimes undertaken in ethnography or fieldwork (discussed in more detail in chapter 10). In the case of covert field research, it may be ethically necessary to conceal information in order to protect the researcher or participants from incurring harm (W. C. van den Hoonaard, 2022).

Activity: Common Ethical Considerations

Test Yourself

- Is harm always of a physical nature? Explain your answer.

- How is beneficence a risk-benefit calculation?

- What is informed consent and what details are included in a consent form?

- How is anonymity different from confidentiality?

- What is debriefing and when is it a requirement?

TRI-COUNCIL POLICY STATEMENT

Research ethics regulations in Canada arose in the late 1970s, largely in response to U.S. policies stemming from the Tuskegee study, controversies surrounding deception in social psychological experiments including Milgram’s, and calls for greater accountability by government-funding agencies (Adair, 2001). Canada’s three federal research funding agencies are the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (NSERC), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC). In 1998, these agencies collectively adopted the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS or the Policy). The Policy is meant to guide researchers in the design of their studies, to promote ethical conduct in the carrying out of research projects, and to establish a process for the ethical review of research involving humans. Research on animals is not considered in this policy, although separate, extensive ethical guidelines exist with respect to animal rights, animal care, and the use of animals in research. The TCPS was expanded into a second edition in 2010 and then updated further in 2014 and again in 2022. It is currently referred to as the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, or TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022) and it serves as the guide to official policies at universities throughout Canada where research takes place.

The overarching value of the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022) is respect for human dignity. Respect for human dignity necessitates that “research involving humans be conducted in a manner that is sensitive to the inherent worth of all human beings and the respect and consideration that they are due” (p. 5). Respect for human dignity is expressed in these three principles: respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justice.

Respect for Persons

As noted in the Belmont Report, respect for persons recognizes the value of human worth as well as the dual need to respect autonomy and protect those with diminished autonomy. The TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022) additionally includes as persons “human biological materials,” such as “materials related to human reproduction” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 7). Respect for persons is demonstrated through the establishment of consent to participate in a study.

Establishment of Consent

There are three important principles that underlie the establishment of consent. First, consent is given voluntarily. This means a subject is freely choosing to participate in the research. Consent is not voluntary in cases where, for example, soldiers are coerced into a study by their superior officers or prisoners participate in a study for fear of negative implications that might result if consent is not provided.

Second, consent is informed by the disclosure of all relevant information needed to understand what participation entails, including all foreseeable risks and benefits. For research intended to involve individuals who lack the capacity to provide informed consent, the individuals must be involved—to the extent possible—in the consent decision-making process, consent must be obtained from an “authorized third party” who is not affiliated with the research team, and the research must have direct benefit for the intended participants (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 31).

Third, consent is an ongoing process. This does not imply that once a person signs a consent form, they have consented to finish the study. Rather, “researchers have an ongoing ethical and legal obligation to bring to participants’ attention to any changes to the research project that may affect them” throughout the course of the study (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 39). A participant may or may not choose to start a study and may elect to discontinue their involvement at any time after starting without penalty. In cases where a participant discontinues involvement, data collected up to the point may also be withdrawn at the discretion of the participant.

Concern for Welfare

Harm has already been discussed in detail, so we won’t reiterate this issue here. In addition to minimizing harm, a concern for welfare entails efforts to mitigate other foreseeable risks associated with participation, such as to housing, employment, security, family life, and community membership. The protection of privacy also falls under a concern for welfare:

Privacy risks arise in all stages of the research life cycle, including initial collection of information, use and analysis to address research questions, dissemination of findings, storage and retention of information, and disposal of records or devices on which information is stored (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 77).

In this case, the promise of keeping data confidential is expanded to include an obligation on the part of a researcher to put safeguards in place for all “entrusted information” so that it is protected from “unauthorized access, use, disclosure, modification, loss, or theft” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 78). Safeguarding information can include physical measures such as locked storage cabinets, administrative considerations such as who has access to information on participants, and technical safeguards such as passwords, firewalls, and encryption measures (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022).

Another concern related to welfare is the special consideration of individuals or groups “whose situation or circumstances may make them vulnerable in the context of a specific research project,” as in the case of impoverished persons where even a slight participation incentive could negate the voluntary nature of consent given (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 66). An example of this is the use of paid participants from poor areas in India, as described in the Research on the Net box “Recruiting the Poor for Clinical Drug Trials.” On the other hand, in certain types of research, including focus groups and qualitative interviews (discussed in chapter 9), it is commonplace to offer participants compensation for their time, such as gift certificates to a local coffee shop or grocery store.

A final application of welfare extends to research involving Indigenous peoples. As noted in chapter 2 and the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022), much of the research carried out on Indigenous peoples has been historically linked to forced assimilation; it was undertaken by non-Indigenous researchers following traditional research approaches, and it was without benefit to Indigenous communities. To date, differences exist between non-Indigenous and Indigenous value systems when it comes to research foundations, and these differences are apparent in the TCPS 2 ethical guidelines that largely focus on individuals (e.g., consent and harm in relation to individual participants), not holistic interrelationships based on trust that are integral to Indigenous communities and research practices. Since non-Indigenous researchers lack training and knowledge when it comes to understanding and adequately accounting for Indigenous community customs, concerns, relationships, and values, the TCPS 2 dedicates an entire chapter (i.e., chapter 9) to research involving First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples of Canada. While this is a starting point and the provisions are meant to serve as a dialogue for interpreting the ethics framework within Indigenous contexts, there are few practical suggestions for how researchers are to go about implementing key requirements, such as community engagement, respect for governing authorities (e.g., community leaders), recognition of diverse interests, and respect for customs (Bull, 2016).

Justice

Recall that justice refers to “the obligation to treat people fairly and equitably” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 9). Fairness means equal concern and respect is shown to all research participants, while equity relates more to considerations of the overall distribution of benefits versus “burdens” incurred by participants in research. Stemming from this is a concern that certain groups are not given the opportunity to participate in research, based on attributes unrelated to the research. For example, women, children, and the elderly are sometimes inappropriately excluded from research because of sex, age, or disability (see chapter 4 in the TCPS 2, CIHR et al., 2022). Notably, researchers seeking to carry out projects that will include Indigenous participants, impact Indigenous communities, or be conducted on First Nations, Inuit, or Métis lands must first be informed about rules and customs that apply to Indigenous peoples and their land, must engage directly with the implicated community in the design and implementation of the project, and must reach prior agreements concerning research expectations, commitments, and ethical considerations with the community involved (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022).

Research on the Net

The First Nations Principles of OCAP®

Along with the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022), researchers working with Indigenous peoples in Canada should familiarize themselves with OCAP. The OCAP principles establish guidelines for how First Nations’ data are collected, protected, used, and shared, emphasizing First Nations’ sovereignty over their own data. OCAP stands for Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession.

Watch this brief YouTube video to learn more: Understanding the First Nations Principles of OCAP™: Our Road Map to Information Governance

Test Yourself

- What is the all-encompassing value of the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022)?

- What three considerations underlie the establishment of consent?

- In what ways might a concern for welfare extend beyond physical and psychological harm?

- What are privacy risks and when do they arise?

- Why are certain individuals and groups especially vulnerable in the context of research?

RESEARCH ETHICS BOARDS AND THE ETHICAL REVIEW PROCESS

The TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022) mandates that all research involving humans be subject to an ethical review by an institutional research ethics board. A research ethics board (REB) is a committee whose role is to “review the ethical acceptability of research on behalf of the institution, including approving, rejecting, proposing modifications to, or terminating any proposed or ongoing research involving humans” (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2022, p. 96).

Membership Requirements

REB members must be qualified to judge the ethical provisions of the research as guided by the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022). At least some of the members of the committee are required to have expertise in research methodologies of the relevant disciplines of the researchers likely to submit applications. In addition, the group must contain ethical and legal expertise as well as someone who can represent the interests of the public, such as a community member not affiliated with the institution.

Ethical Review Process

All research that is conducted by individuals affiliated with an institution, such as faculty members or professors, is conducted at a university using that institution’s assets (e.g., a classroom, equipment), or includes students or staff members from a university as participants in research needs to be approved in advance by the review board. Even research conducted using web-based sources needs to undergo review if it is deemed “engaged,” where a researcher may, for example, join an online community to study it. However, other forms of research that are conducted using publicly available sources of information, such as X posts or the content in other forms of media, such as Netflix episodes, are generally not subject to ethical review processes. The formal process begins with the researcher completing an application for review.

Ethical Review Application Form

As directed by the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022), an ethical review application at a university in Canada includes background information on the main or principal researcher, the affiliated institution, and the other investigators on the project. Also included are details about the proposed project, including the start and end date, the location where the study will be conducted, and other relevant specifics, such as ethical approval received or sought from other institutions and applicable funding sources. Researchers are required to provide a summary of their proposed project objectives and a brief literature review of the topic, and indicate the main hypotheses or research questions examined. An application also includes detailed information about the research participants, such as the number sought, the characteristics relevant to recruitment, and the ways in which the participants will be solicited.

In keeping with concerns for harm, researchers must disclose details of all known risks as well as any other foreseeable concerns stemming from participation. Researchers also need to provide justifications for any harm incurred and need to explain how safeguards or resolutions will be built into the study. The procedures to be used in the study are described in detail, including how informed and voluntary consent will be secured, how privacy will be respected, and how consent will be obtained. In cases where information is withheld from participants, explicit justification must be provided. Researchers also include details regarding when and how participants will be debriefed, if applicable, and their plans for the retention and disposal of data.

The application is typically submitted to the chair of the REB or through a web-based portal to a research office, along with any other kind of supporting documents deemed relevant in relation to the particular study, such as an advertisement for participant recruitment, an indication of ethical approval from another institution, an interview script or set of interview question guidelines, a participant informed-consent form, and/or a questionnaire or survey items.

Research Ethics Board Decision

Research ethics board members typically meet on a published schedule (e.g., once a month) to review research applications and render a decision about the ethical acceptability of the proposed research, as guided by the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022). A decision is provided in writing to the researcher on behalf of the institution. It generally takes the form of an approval with no conditions, an approval subject to the conditions or proposed modifications provided by the committee, or a rejection on the grounds that the research project is deemed unethical for the reasons indicated.

Test Yourself

- What is a research ethics board and what is its role in relation to research?

- What kinds of study details are essential to include in an ethical review application form?

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- Define research ethics and provide examples of research-related ethical conduct.

Research ethics refer to an array of considerations that arise in relation to the morally responsible treatment of humans in research. For example, ethical conduct includes minimizing the risk of harm to participants, treating participants fairly, equitably, and with respect, ensuring participants have provided informed and voluntary consent, and safeguarding privacy. - Recognize links between early military research and regulatory outcomes.

Much of the early research conducted by Nazi doctors and military personnel involved severe injury or death for victims, who were forced to participate in experiments against their will. The Nuremberg Code consists of 10 ethical guidelines outlining safeguards for experiments, including the importance of obtaining informed and voluntary consent, providing justification for a study based on its overall merits versus potential for causing harm, minimizing the potential for harm, and giving subjects the liberty to withdraw their participation at any time. The Belmont Report comprises three main principles: respect for persons (a principle recognizing the autonomy and worth of individuals), beneficence (a principle stressing the importance of maximizing benefits and minimizing harm), and justice (a principle underlying socially responsible behaviour). - Discuss ethical considerations raised by classic studies in social research.

In Stanley Milgram’s experiments on obedience to authority, participants were harmed by the belief that they were administering painful electric shocks to another participant. In Philip Zimbardo’s simulated prison study, prisoners were harmed by the aggressive and abusive tendencies that developed in the guards. - Discuss the potential for harm, risk-benefit analysis, informed consent, privacy and confidentiality, and debriefing as major ethical considerations in social science research.

Researchers attempt to design studies in a manner that minimizes the risk of any form of harm, such as physical or psychological. Informed consent refers to an autonomous process whereby participants are provided with the relevant details needed to make a judgment about whether or not to participate in a study. Anonymity exists if a researcher cannot link individual responses to the person who provided them. Confidentiality is a process for maintaining privacy wherein the researcher ensures that a participant’s identity will not be publicly disclosed. Debriefing refers to a full disclosure and exchange of information regarding all aspects of the study. - Identify the core principles that underlie the Tri-Council Policy Statement, TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022).

The overarching value of the TCPS 2 is respect for human dignity, expressed as respect for persons (i.e., human worth), concern for welfare (i.e., quality of life), and justice (i.e., fair and equitable treatment). - Describe the role of an ethics review board and outline the process for undergoing an ethical review of research.

The role of an ethics review board is to review the ethical acceptability of research on behalf of an institution, including approving, rejecting, proposing modifications to, or terminating any proposed or ongoing research involving humans. Researchers submit an application that summarizes a proposed study, along with the relevant ethical considerations, to the chair of the REB, the REB reviews the application, and the researcher is provided with a written decision.

RESEARCH REFLECTION

- Imagine you are a member of a research ethics board and the chair of the REB has asked you to come of up with criteria for assessing the level of risk in social research. Develop criteria and/or provide examples to illustrate “low or minimal risk,” “moderate risk,” and “probable harm or high risk.”

- Watch the award-winning 2018 documentary: Three Identical Strangers directed by Tim Wardle to learn about triplets named Edward Galland, David Kellman, and Robert Shafran who were separated at birth as part of an undisclosed study on the effects of nature versus nurture. Using this real-life story, identify examples of violations of respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justice.

- Become an expert on the TCPS 2 (CIHR et al., 2022). The Government of Canada’s Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics offers an online tutorial for free: TCPS 2: CORE-2022 (Course on Research Ethics). This condensed course is designed to help researchers, members of research ethics boards, educators, students, and others become familiar with the TCPS 2. Upon completion, you will receive an official certification.

- The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) supports Indigenous research. To learn about Indigenous-led research, visit Indigenous Research on the SSHRC website.

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE

Objective: To evaluate ethical issues in social research

Directions:

- Locate and read: Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? American Psychologist, 64(1), 1–11.

- Describe the central research question and summarize the main procedures used to carry out the study on obedience.

- Explain how the replication attempts to resolve for specific ethical implications raised in Milgram’s original experiment. Do you think the changes accomplish this? Why or why not?

- If you were a member of an institutional ethics review board, would you grant approval to this study with no conditions, provide approval but require changes to the study, or fail to grant approval? Justify your answer by referencing the main ethical issues discussed in this chapter.

RESEARCH RESOURCES

- For guidance on ethical issues related to visual forms of data, particularly in relation to data acquisition and data sharing, see Levin, M. et al. (2024). Visual digital data, ethical challenges, and psychological science. American Psychologist, 79(1), 109–122.

- For information on ethical issues as they relate to visual representations in research, see “Ethics and visual research” in Banks, M., and Zeitlyn, D. (2015). Visual methods in social research (pp. 122–126). Sage.

- To learn more about ethical dilemmas concerning qualitative research, see Gallagher, K. (Ed.). (2018). The methodological dilemma revisited: Creative, critical, and collaborative approaches to qualitative research for a new era. Routledge.

- To read about the Tuskegee syphilis study in more detail, refer to Jones, J. H. (1993). Bad blood: The Tuskegee syphilis experiment. The Free Press, and Gray, F. D. (2013). The Tuskegee syphilis study. NewSouth Books.

Conduct that is considered “morally right” or “morally wrong,” as specified by codified and culturally ingrained principles, constraints, rules, and guidelines.

An array of considerations that arise in relation to the morally responsible treatment of humans in research.

A set of ethical directives for human experimentation.

A moral principle stressing that researchers respect the human participants in their investigations as persons of worth whose participation is a matter of their autonomous choice.

A moral principle outlining that in the planning and conducting of research with human participants, the researcher maximizes the possible benefits and minimizes the potential harms from the research.

A moral principle of rightness claiming that in the course of research, researchers behave and make decisions in a manner that demonstrates social responsibility in relation to the distribution of harm versus benefits.

A process where potential participants are provided with all relevant details of the study needed to make a knowledgeable judgment about whether to participate in it.

A state of being unknown. In the case of research, this means a researcher cannot link any individual response to its originator.

The process of maintaining privacy. In research, this means even when a participant’s identity is known to the researcher, steps are taken to make sure it is not made public.

The full disclosure and exchange of information that occurs upon completion of a study.

A value necessitating that research involving humans be conducted in a manner that is sensitive to the inherent worth of all human beings and the respect and consideration that they are due.

Steps taken to protect the welfare of research participants, in terms of both harm and other foreseeable risks associated with participation in a given study.

A committee whose mandate is to review the ethical acceptability of research on behalf of the institution, including approving, rejecting, proposing modifications to, or terminating any proposed or ongoing research involving humans.