Chapter 2: The Importance of Theory and Literature

There is nothing more practical than a good theory.

— Kurt Lewin, 1951, p. 169

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

- Outline the main assumptions of positivist, interpretive, critical, and pragmatic paradigms.

- Explain why decolonization is necessary for learning about Indigenous knowledges.

- Define and differentiate between theoretical frameworks and theories.

- Distinguish between deductive and inductive reasoning and explain how the role of theory differs in qualitative and quantitative research.

- Formulate social research questions.

- Explain the importance of a literature review.

- Locate appropriate literature and evaluate sources of information found on the internet.

INTRODUCTION

In chapter 1, you were introduced to scientific reasoning as a desirable alternative to learning about the social world through tradition, common sense, authority, and personal experience. In addition, you learned to distinguish between basic and applied research and that research methods are used to collect data for a variety of purposes (e.g., to explore, describe, explain, or evaluate some phenomenon). In this chapter, you will learn about paradigms that shape our views of social research and alternative worldviews in the form of Indigenous knowledges. You will learn about theoretical frameworks and the importance of theory and prior research for informing the development of new research. Finally, this chapter helps you locate and evaluate sources of information you find in the library and on the internet.

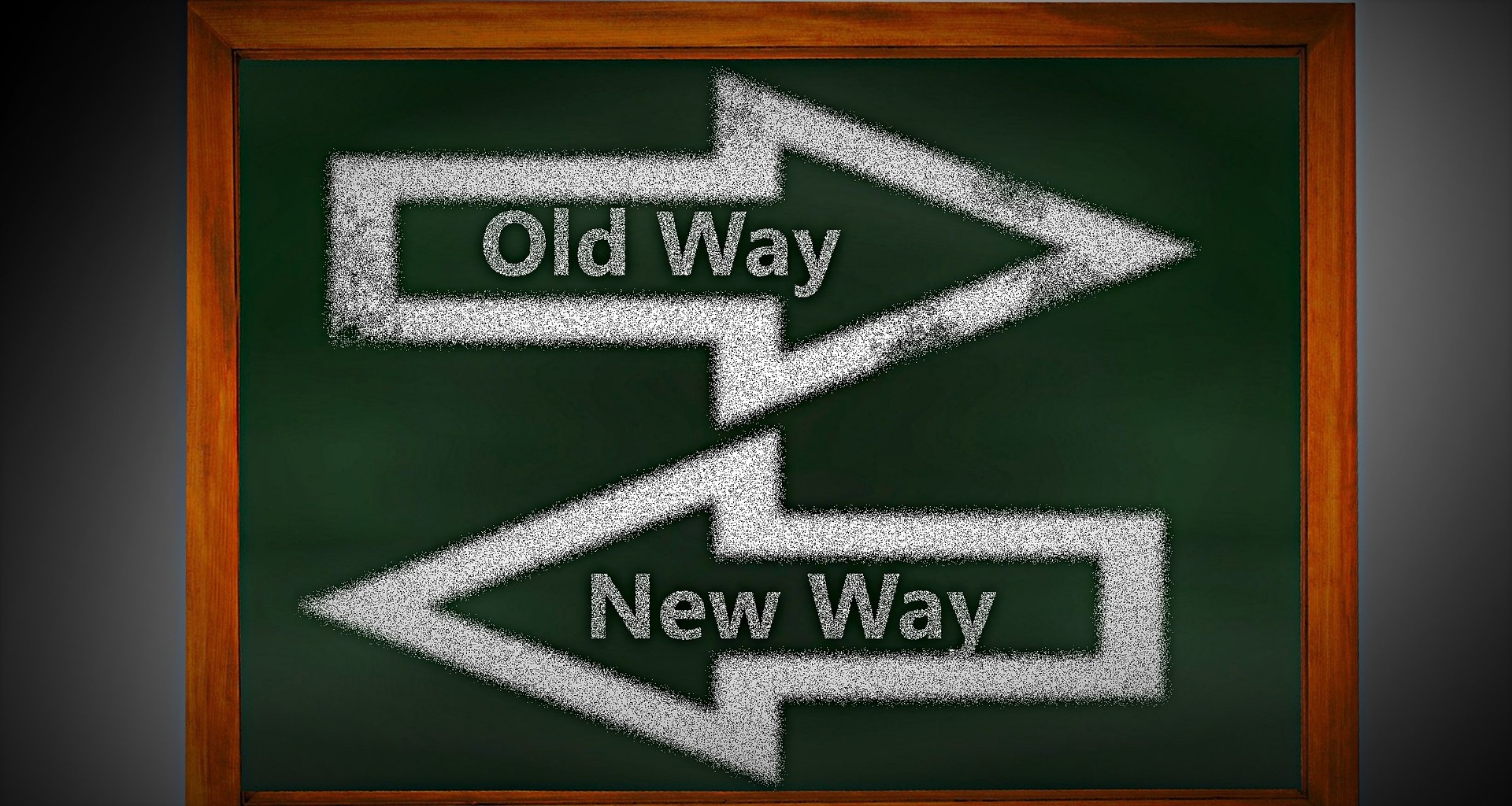

INQUIRY PARADIGMS IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES

At the most general level, a paradigm is a set of “basic beliefs” or a “worldview” that helps us make sense of the world, including our own place in it (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). Earl Babbie and Jason Edgerton (2024) define a paradigm as “a theoretical perspective including a set of assumptions about reality that guide research questions” (Some Social Science Paradigms section). As a broad framework, a paradigm includes assumptions about the nature of knowledge (a branch of philosophy called epistemology), assumptions about the nature of reality or the way things are (a branch of philosophy called ontology), and assumptions about how we go about solving problems and gathering information (a system of principles or practices collectively known as methodology). The assumptions are interrelated in the sense that how one views the nature of reality (an ontological stance) influences beliefs about one’s relationship to that reality (an epistemological stance) and how one would go about examining that reality (a methodological stance) (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). This will become clearer as we compare the assumptions of four distinct and competing inquiry paradigms.

Positivist Paradigm

French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857) first used the term social physics (later called sociology) to describe a positivist science of society that could teach us about the social world through research and theorizing (Ritzer & Stepnisky, 2021). The positivist paradigm is a belief system aimed at discovering universal laws based on the assumption that a singular reality exists independent of individuals and their role in it. Positivism rests on a worldview like that of the natural sciences, which stresses objectivity and truth as discovered through direct empirical methods. In its most extreme form, positivism will accept as knowledge-only events that can verified through sensory experience (Bell et al., 2022). The goal of positivism is to explain events and relationships via a search for antecedent causes that produce outcomes. Within a positivist paradigm, the search for empirical truth begins with what is already known about an area. From that starting point, probable causes are “deduced” using logical reasoning, and then theories are tested for accuracy. Systematic observation and experimental methods are commonly employed modes of inquiry and the data obtained is quantifiable.

Interpretive Paradigm

The interpretive paradigm (also called constructivism) arose in part as a critique of positivism for its failure to recognize the importance of subjectivity in human-centred approaches. The interpretive paradigm worldview rests on the assumption that reality is socially constructed in the form of mental representations created and recreated by people through their experiences and interactions in social contexts (Lincoln et al., 2024). As such, “multiple realities exist” for any given individual (Guba, 1996), and these individual realities are largely “self-created” (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). The focus of the interpretive paradigm is on understanding individuals’ perceptions of reality, including how events and interactions come to have meaning for them, rather than identifying objective phenomena or social facts that exist outside of individuals and relationships. This generally necessitates a qualitative research strategy, such as ethnography, which brings the researcher into close contact with those being studied for prolonged periods of time; as a result, relationships develop and insight is gained from within those relationships. As Palys and Atchison (2014) put it, “good theory is not imposed; rather, it emerges from direct observation and contact with people in context” (p. 23).

Critical Paradigm

Another worldview that emphasizes interpretation and understanding is the critical paradigm. The critical paradigm rests on an assumption that “human nature operates in a world that is based on a struggle for power” (Lincoln et al., 2024, p. 81). The critical paradigm focuses specifically on determining the role power plays in the creation of knowledge, frequently using qualitative strategies. The critical approach is more of a critique concerning how and why particular views become the dominant ones and how privilege and oppression interact, often as the result of defining characteristics such as gender, race and ethnicity, and social class (Lincoln et al., 2024). Beyond examining inequality, there is also an emphasis on “praxis,” whereby scholars provide knowledge that can help to end powerlessness (Symbaluk & Bereska, 2022). To the extent that research can identify ways in which groups are disadvantaged and identify the causes of subordination, it can also be used to help resolve the inequities. Various theoretical perspectives and theories stem from a critical-interpretative stance including feminist inquiry, critical race theory, critical disabilities studies, and queer theory.[1]

Pragmatic Paradigm

Finally, in contrast to the dichotomy between the objectivity of positivism and the subjectivity of interpretive approaches, an impartial outlook is offered by a more recent paradigm called the pragmatic paradigm. The pragmatic view “arises out of actions, situations, and consequences rather than antecedent conditions” and is concerned with “applications—what works—and solutions to problems” (Creswell & Creswell, 2023, p. 11). This problem-centred worldview is not based in any philosophy, nor does it necessitate the use of a certain form of reasoning or research technique. It does, however, emphasize the importance of methodology for solving problems and advocates for the use of combined qualitative and quantitative approaches for a more complete understanding. Historically, combining qualitative and quantitative approaches has proven problematic given the opposing assumptions upon which each approach is based. The pragmatic paradigm offers a solution to the dichotomy. As John W. Creswell and J. David Creswell (2023) note, “pragmatists do not see the world as an absolute unity. In a similar way, mixed methods researchers look to many approaches for collecting and analyzing data rather than subscribing to any one way (e.g., quantitative or qualitative)” (p. 12). Thus, the starting point is the issue or research problem, which itself suggests the most applicable means for further research exploration. Mixed method approaches to research that are grounded in a pragmatic paradigm are discussed in more detail in chapter 11.

Test Yourself

- Which paradigm seeks to discover universal laws?

- Which paradigm is most concerned with objective reality?

- Which paradigm is problem-centred?

- Which paradigm rests on the assumption that reality is socially constructed?

INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGES AND RESEARCH PARADIGMS

It is important to note that the paradigms discussed thus far have philosophical and research underpinnings based on dominant Euro-Western modes of thought. Indigenous scholars highlight the value of reclaiming alternative worldviews stemming from the silenced cultural perspectives of groups that are marginalized, underprivileged, and/or have suffered European colonization (e.g., see Battiste, 2000; Belanger & Hanrahan, 2022; Quinless, 2022; Smith, 2021; Warrior, 1995). “Indigenous knowledges are diverse learning processes that come from living intimately with the land, working with the resources surrounding the land base, and the relationships that it has fostered over time and place. These are physical, social, and spiritual relationships that continue to be the foundations of its world views and ways of knowing that define their relationships with each other and others” (Battiste, 2013, p. 33). These Indigenous, sometimes called “traditional,” knowledges contain a wealth of pragmatic lessons in diverse areas from environmental conservation to cultural protocols and familial relationships.

The loss of language stemming from forced assimilation via structural mechanisms such as residential schools and Eurocentric educational systems poses challenges for the maintenance of Indigenous knowledges, though elders continue to play a vital role in the verification and transmission of Indigenous cultures. Note that researchers and their methods used to research Indigenous knowledges have historically been mainly non-Indigenous, and hence even the discourse of the colonized is shaped “through imperial eyes” (Smith, 2021). By employing decolonized methods, involving Indigenous researchers, including Indigenous peoples as active participants in research processes, listening to the teachings of elders, and recognizing the role that non-Indigenous researchers and Western methodologies have played in shaping the discourse on colonized Others, we can begin to remove the Eurocentric lens. The term colonized Other is used here to refer to Indigenous peoples in Canada who have experienced European colonization, but it can also be used more collectively to include those who are “disenfranchised” and “dispossessed” elsewhere in the world (e.g., those living in marginalized communities in underdeveloped countries) as described by Chilisa (2020, p. 9).

Decolonization is not one type of methodology but rather is “a process of conducting research in such a way that the worldviews of those who have suffered a long history of oppression and marginalization are given space to communicate from their frames of reference” (Chilisa, 2020, p. 11). For example, instead of asking volunteers to complete a questionnaire worded by the researcher to learn about participants’ views and experiences as prescribed by traditional social science methods, a former student of one of the authors named Reith Charlesworth (2016) spent several months developing relationships and establishing trust with program attendees before participating in a sharing circle she co-facilitated with an Indigenous social worker. The sharing circle included a feast and provided the opportunity for women to tell stories that ultimately helped Reith better understand social and structural barriers experienced by young Indigenous mothers in a parenting program at iHuman Youth Society in Edmonton, Alberta.[2]

Since Indigenous knowledge structures encompass a dynamic array of beliefs and lived experiences held by various individuals identifying with vastly different tribal groups in many different locations, it is difficult to identify common features. The United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization defines local and Indigenous knowledge as the

understandings, skills and philosophies developed by societies with long histories of interaction with their natural surroundings. For rural and Indigenous Peoples, local knowledge informs decision-making about fundamental aspects of day-to-day life. This knowledge is integral to a cultural complex that also encompasses language, systems of classification, resource use practices, social interactions, ritual and spirituality.” (UNESCO, 2024)

In her book on Indigenous methodologies, Margaret Kovach (2021) explains:

The scope and basis of an Indigenous epistemology encompasses:

- multiple sources of knowledge, more commonly recognized as holism (scope);

- a tangible and intangible animate world that is process oriented and cyclical, such as that expressed in verb-oriented language (e.g., with ing endings), which comprise many Indigenous languages (basis); and

- a web of interdependent, contextual, relationships over time, such as with place, family and community (basis)(p. 68).

Whereas the aim of a positivist paradigm is to discover universal laws, an Indigenous research paradigm seeks to challenge colonized ways of thinking and to employ decolonized research methods that enable a respectful reclaiming of Indigenous cultures and knowledges. Because Indigenous knowledges are largely maintained through oral transmission and cultural practices, Indigenous methodologies also include ceremonies and formal protocols, and they are amenable to narrative inquiry as in the case of sharing circles and storytelling (Kovach, 2021). When it comes to employing Indigenous research methods, the fundamental point to remember is that the research process and the resulting data and knowledge stemming from it are integrally based on “relational actions”—that is, the personal relationships and connections that are formed with Indigenous communities based on trust (Kovach, 2021).

Test Yourself

- What are Indigenous knowledges?

- In research, what does decolonization mean?

Activity: Understanding Research Paradigms

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS AND THEORIES

Positivist, interpretive, critical, and pragmatic paradigms all offer a broad worldview from which theoretical frameworks emerge. Theoretical frameworks are perspectives based on core assumptions that provide a foundation for examining the social world at different levels. Theoretical frameworks that operate at the macro level tend to focus on “larger social forces,” while those dealing with the micro level are aimed at understanding “individual experiences” (Symbaluk & Bereska, 2022, p. 4).

Within the discipline of sociology, the functionalist, conflict, interactionist, feminist, and postmodern frameworks provide different lenses from which we can view society. The functionalist framework is a macro-level perspective that views society as being made up of certain structures—such as the family, education, and religion—that are essential for maintaining social order and stability. For example, a primary function of the family is to provide for the social, emotional, and economic well-being of its members and to serve as a key agent of socialization. The functionalist framework is rooted in positivism in its focus on observables in the form of social facts and universal truths. The conflict framework is also a macro-level perspective, but it is rooted in the critical paradigm in its examination of power and its emphasis on the prevalence of inequality in society as groups compete for scarce resources. Karl Marx (1818–1883), considered a key founder of this perspective, emphasized the central role of the economy in the creation of conflict and explained how workers in society are exploited and alienated under systems of capitalism (Ritzer & Stepnisky, 2021).

The symbolic interactionist framework is a micro-level perspective attributed to the early work of sociologists George Herbert Mead (1863–1931) and Herbert Blumer (1900–1987). The symbolic interactionist framework depicts society as consisting of individuals engaged in a variety of communications based on shared understandings (Symbaluk & Bereska, 2022). The emphasis here is on how individuals create meaning using symbols and language. Note how this framework emerges from interpretivism, with its emphasis on the importance of subjective meaning for individuals that is constructed and interpreted within interactions. For example, although two siblings in a familial union understand and relate to each other based on common features, such as a shared language and upbringing, they also each experience and recall events somewhat differently, based on their unique perspectives and relations toward one another. The symbolic interactionist perspective often guides qualitative researchers as they design strategies for uncovering meaning in groups and contexts.

With roots in the critical paradigm, the feminist framework[3] rests on the premise that men and women should be treated equal in all facets of social life (e.g., family, employment, law, and policy). The feminist framework includes a diverse range of perspectives (e.g., radical, socialist, post-colonial), operates at both the micro and macro levels, and is especially helpful in demonstrating ways in which society is structured by gender and how gender roles differentially impact males and females. For example, feminist scholars are quick to point out that women in relationships with men continue to adhere to traditional gender role expectations, doing more than their share of housework and experiencing less free time compared to their partners (e.g., Bianchi, 2011; Guppy & Luongo, 2015). Even in egalitarian relationships (based on equality in principle) where both partners are Canadian academics working outside of the home, women assume more of the caregiving and household obligations at the expense of work-life balance (Wilton & Ross, 2017). COVID-19 exacerbated gender inequalities with Canadian women spending close to 50 hours per week more than men on childcare during the pandemic (Johnston et al., 2020).

Finally, emerging post-World War II, the postmodern framework emphasizes the ways in which society has changed dramatically, particularly in relation to technological advances. The postmodern framework speaks out against singular monolithic structures and forces. It traces the intersectional features of inequality, including race, class, and gender, and focuses specifically on the effects of the digital age. This framework complicates dualistic boundaries between the micro and macro (arguing that they are one and the same) and calls into question the singular truths of earlier frameworks such as Marxism and functionalism. Postmodern perspectives are especially helping in guiding research in areas of media literacy, globalization, and environmental studies.

Drilling down another layer, within broader theoretical perspectives, we can locate particular theories. Within the functionalist framework, for example, we find Robert Merton’s (1938) strain theory of deviance, which explains how people adapt when there is a discrepancy between societal goals (what we are supposed to aspire to) and the legitimate means for obtaining them. Or, within the symbolic interactionist perspective, we can locate Edwin Lemert’s (1951) labelling theory of deviance, which explains a process whereby people may come to view themselves as lifelong deviants. Theories are discussed in more detail in the next section.

THE ROLE OF THEORY IN RESEARCH

A theory “is a set of propositions intended to explain a fact or a phenomenon” (Symbaluk & Bereska, 2022, p. 9). The propositions are usually expressed as statements that reflect the main assumptions of the theory. For example, Edwin Sutherland’s (1947) differential association theory is a theory about crime, and it is explained in nine propositions. To give you a sense of the theory, the first proposition is that “criminal behaviour is learned”; the second is that “criminal behaviour is learned in interactions with other persons in a process of communication” (p. 6). Taken together, the propositions in differential association theory explain how crime is learned through interactions with others in much the same way as non-criminal behaviour is learned. That is, members of small groups with whom we spend time and who we feel are important may teach us the techniques and motives needed to develop criminal tendencies.

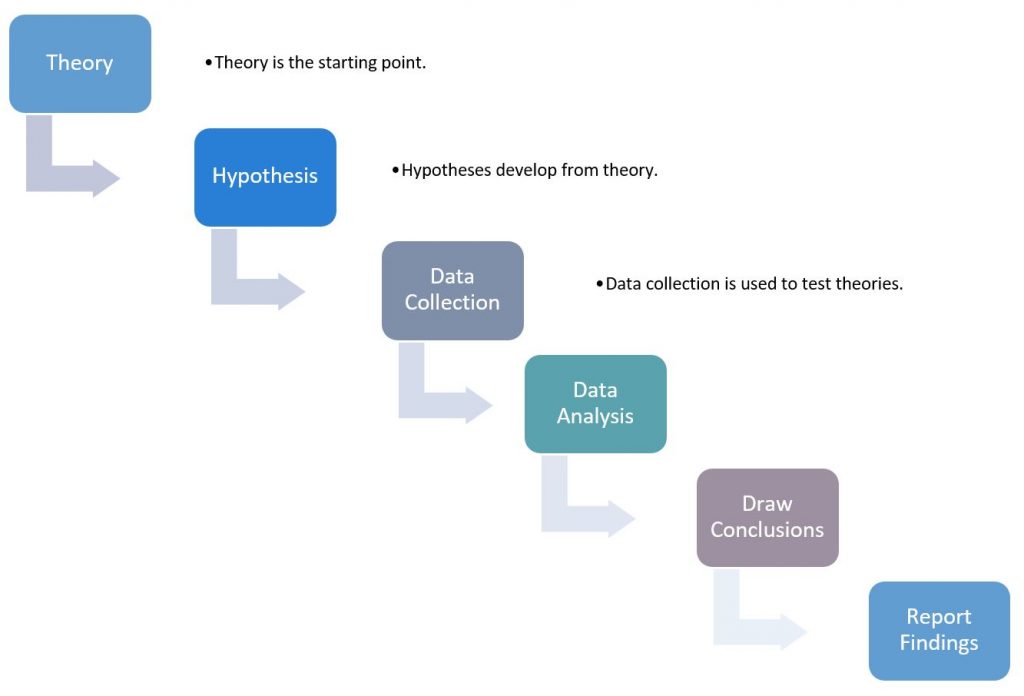

Deductive Forms of Reasoning

Theory doesn’t happen in isolation from research; it can both inform the research process and develop from it. Theory that informs the research process is known as deductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is a “theory-driven approach that typically concludes with [empirical] generalizations based on research findings” (Symbaluk & Bereska, 2022, p. 26). A deductive approach to social research is often a “top-down” linear one that begins with a research idea that is grounded in theory. A hypothesis or “testable research statement that includes at least two variables” is derived from the theory and this sets the stage for data collection (Symbaluk & Bereska, 2022, p. 29). A variable is a “categorical concept for properties of people or entities that can differ and change” (Symbaluk & Bereska, 2022, pp. 25–26; as discussed in more detail in chapter 4). In a study on crime, criminal behaviour (e.g., the presence or absence of it) or a certain type of crime is likely to be a main variable of interest, along with another variable regularly associated with crime, such as age, sex, or race. For example, based on a theory of aggression, a hypothesis could be that men are more likely than women to commit physical assaults.

Activity: Deductive Research Process

Testing Hypotheses Derived from Theories

Based on the tenets of Sutherland’s (1947) differential association theory, Reiss and Rhodes (1964) “deduced” that delinquent boys are likely to engage in the same acts of deviance as their closest friends, since these are the people from whom they learn the techniques, motives, and definitions favourable to committing crimes. Specifically, they tested a hypothesis that the probability of an individual committing a delinquent act (e.g., auto theft, an assault, and vandalism) would be dependent upon his two closest friends also committing that act. The researchers looked at six different delinquent acts among 299 triads (i.e., groups of three), wherein each boy reported on his delinquency and indicated whether he committed the act alone or in the presence of others. In support of the theory, Reiss and Rhodes (1964) found that boys who committed delinquent acts were more likely to have close friends that committed the same acts. Figure 2.2 summarizes the logic of a typical research process based on deductive reasoning.

Inductive Forms of Reasoning

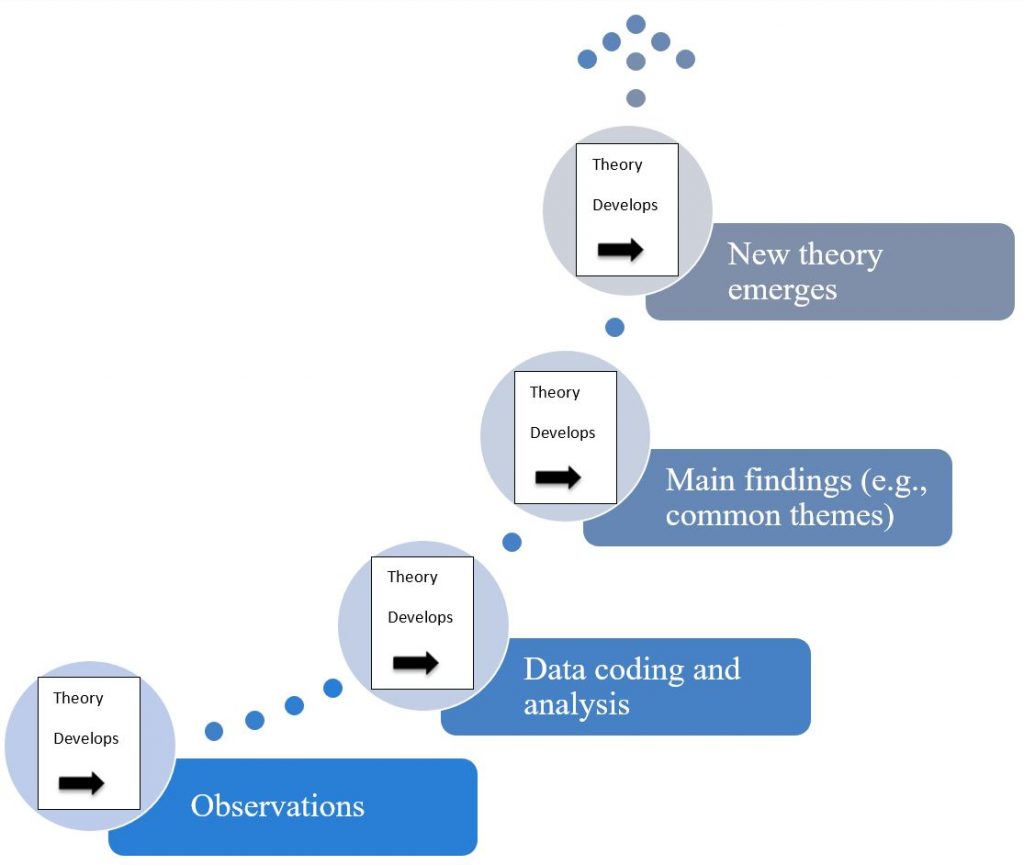

An inductive reasoning approach is more “bottom-up,” beginning with observations and ending with the discovery of patterns and themes that are usually informed by theory or help establish and thereby “induce” new theory (see figure 2.3).

For example, Lowe and McClement (2011) examined the experience of spousal bereavement through interviews with young Canadian women whose husbands passed away. Over the course of data collection, the researchers identified various common themes including “elements of losses” such as the loss of companionship and the loss of hopes and dreams for the future. They also identified a notion of “who am I?” as the widows relayed their attempts to redefine themselves as single, in relation to other men, with their friends, and as single parents. Although the lived experience of young Canadian widows as a specific group of interest had not been previously explored, the researchers interpreted their findings within the context of previous studies and theoretical frameworks, such as Bowman’s (1997) earlier research on facing the loss of dreams and Shaffer’s (1993) dissertation research on rebuilding identity following the loss of a spouse. Lowe and McClement (2011) also identified the importance of making connections through memories as a means of adapting, suggesting a direction for additional research and the potential for an eventual theory on the development of relationships following the loss of a spouse.

The Role of Theory in Quantitative and Qualitative Research

Note that the role and use of theory differs depending on whether the study is quantitative (i.e., based on deductive reasoning) or qualitative (i.e., based on inductive reasoning). Recall from chapter 1 that qualitative research often seeks to provide an in-depth understanding of a research issue from the perspective of those who are affected first-hand. The research process begins with an interest in an area such as cannabis use and a research question (e.g., What do parents perceive their role to be in the education of cannabis use?). Data collection is often undertaken through a technique such as qualitative interviews, where researchers ask open-ended questions to learn as much as possible from interviewees. For example, Haines-Saah et al. (2018) asked parents of adolescent drug users what their experiences were like talking to their children about drug use. Theory is usually brought into an analysis to help make sense of the responses collected. In some cases, new theory develops out of the research findings. The “discovery of theory from data systematically obtained from social research” is better known as grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 2007, p. 2) since it is intricately linked to the data and context within which it developed. In most instances of qualitative research, theory plays a central role at various stages (e.g., in the formulation of the research question, in the initial stages of data coding, and especially toward the end of the data-analysis process). Findings from the cannabis study were interpreted in theoretical frameworks of risk and responsibility, as parents discussed cannabis use largely from a health narrative of drugs negatively impacting a developing brain or a blame narrative where parents viewed themselves as the primary agents of prevention (Haines-Saah et al., 2018).

In contrast, theory is the starting point for most quantitative studies. On one hand, a theory provides a set of interrelated ideas that organize the existing knowledge in a meaningful way and help to explain it (Cozby et al., 2020). For example, demographic transition theory helps to identify universal stages of population change as countries progress from pre-industrial societies through to post-industrial economies (Landry, 1934; Notestein, 1945). In countries characterized by the more advanced industrial stage of development, birth rates are low, corresponding to people having fewer children due to various considerations (e.g., birth control, female participation in the workforce, reliance on exported manufactured goods, greater emphasis on higher educational attainment). Despite the specificity of economic and social issues that vary from one country to the next, we can still identify broader commonalities such a declining birth rate coupled with an already low death rate in all countries that have reached the industrial stage of development, including Canada. Hence, this early theory is still useful today for explaining differences between countries in early industrial, industrial, and post-industrial stages of development.

In addition, a theory provides a focal point that draws our attention to issues and events in a manner that helps to generate new interest and knowledge (Cozby et al., 2020). For example, conflict theorists showed us how capitalism and its focus on economic productivity is linked to major environmental issues, including the high extraction of natural resources and the high accumulation of waste (Schnaiberg, 1980). Schnaiberg’s early framing of capitalism as a “treadmill of production” spawned additional interest in the study of modern industry, highlighting ways in which environmental issues are constructed as “proeconomic” measures in part because of alliances formed between capitalists, workers, and the state (Gould et al., 2008). Conflict theorists also direct our attention to the capitalist “treadmill of accumulation,” which, in its reliance on ever-increasing amounts of expansion and exploitation, renders attempts at sustainable capitalism largely unattainable from an environmental standpoint (Foster et al., 2010). With ongoing concerns about carbon emissions, conflict theorists are now asking the question: How much is enough? suggesting we need to aim for carbon minimalism through efforts at simplicity and sufficiency if we hope to tackle the climate crisis (Alter, 2024).

On the other hand, using theory as a starting point necessitates the development of specific propositions and the prior classifications of key concepts and assumptions before data collection begins. As Mathew David and Carole D. Sutton (2011) explain,

there are advantages and disadvantages here. Those who seek to classify their qualities prior to data collection can be accused of imposing their own priorities, while those who seek to allow classifications to emerge during the research process are thereby unable to use the data collection period to test their subsequent theories. They too can then be accused of imposing their own priorities because it is hard to confirm or disprove their interpretations as no ‘testing’ has been done. (p. 92)

You will learn more about the criteria used to evaluate research in chapter 4. For now, consider that both approaches, while different, have equal merit and drawbacks. Inductive and deductive approaches are probably best viewed as different components of the same research cycle, with some researchers beginning with theories and ending with observations, and others doing the reverse (Wallace, 1971).

Research on the Net

Classical Social Theory Course

Classical social theory remains highly relevant today, guiding and informing the research of social scientists around the world. Professors at the University of Amsterdam have developed a free online course on Classical Social Theory for anyone interested in learning more about the works of influential social science theorists from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, including Karl Marx, Max Weber, and Emile Durkheim.

Test Yourself

- What is theory?

- What does a hypothesis contain?

- In what ways is a research process based on deductive reasoning different from one based on inductive reasoning?

- How do the role and use of theory differ in a qualitative versus quantitative study?

- What is grounded theory?

FORMULATING RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Although most of this chapter has focused on the role of theory for guiding the development of research and helping to inform research outcomes, research begins even before this, with a general area of interest. Every research study begins with a topic of interest. As a general worldview can be narrowed into a specific theory, a general area of interest can be shaped into a specific research question. Think about the last time you were asked to write an essay on a topic of interest or if you are considering continuing your studies into graduate school, what a general area of interest might entail. For a student in sociology, a broad area of interest could be the family, gender and sexualities, deviance, globalization, or social inequality. A student in psychology is more likely to consider the areas of developmental psychology, cognition, neuropsychology, or clinical testing, to name a few. Someone in anthropology may have a starting interest that lends itself more to archaeology, physical anthropology, cultural anthropology, or linguistics.

Locating a Topic of Interest

Within a broad area of interest, there are topics or issues that are focus points for research. For example, a sociologist specializing in social inequality might wish to learn more about the distribution of poverty in Canada or the barriers to housing experienced by those who are homeless. A developmental psychologist may be studying the intellectual, emotional, or perceptual development of children. Someone in anthropological linguistics might be interested in the evolution of language dialects or the loss of a mother tongue over time. Regardless of the topic you choose, your research interest is likely to centre on social groups (e.g., homeless people, children with developmental delays, Indigenous peoples who speak an endangered language) or social structures, policies, and processes that affect groups (e.g., barriers to housing, definitions of poverty, cannabis legislation, health benefit coverage).

Framing an Interest into a Social Research Question

Recall from chapter 1 that a social research question is designed to explore, describe, explain, or critically evaluate a topic of interest. This means as you develop your topic of interest, you need to consider how the wording of the question suggests the most appropriate course of action for answering it. A social research question is “a question about the social world that one seeks to answer through the collection and analysis of firsthand, verifiable, empirical data” (Schutt, 2022, p. 33). A question beginning with “What is it like to …” often implies an exploratory purpose, inductive reasoning, and a qualitative research method. A question beginning with “Why” may presuppose a search for causes, and this is generally undertaken for an explanatory purpose based on deductive reasoning and a quantitative method, such as an experiment. Alternatively, “Why” might also imply inductive reasoning that is designed to get the essence of a first-hand experience using a qualitative approach. Research questions that are designed to evaluate a program or service are likely to be formulated along the lines of “Is this working?” Program evaluations are often based on qualitative methods, but the approaches and methods vary considerably and may include mixed methods, depending on the nature of the program or policy. Descriptive studies, often resting on a research question such as “What are its main features?” tend to be heavily represented in the quantitative realm (especially when the data are gathered through surveys). However, like evaluation research, descriptive studies are amenable to qualitative methods, especially in the case of field observation, which can produce highly descriptive forms of data.

Framing an interest is not a process that occurs instantly; rather it is one that you develop over time, eventually shaping your interest into a manageable research question that will direct a study that contributes to the existing body of knowledge. You will need to start with a general area, select a topic, issue, or focus within that area, and then look at the literature before refining your topic into a central social research question. Figure 2.4 provides two examples of the progression from a general area to a more specific question.

Test Yourself

- What does a research study begin with?

- What is a social research question?

THE IMPORTANCE OF A LITERATURE REVIEW

If you plan to conduct research, you will need to be familiar with what is already known about your research interest before you finalize your research question. It is important that you at least examine the literature relevant to your topic of interest before you commit to a specific research question. You are likely to modify your research question once you learn more about the topic from a literature review.

A literature review is essential for these reasons:

- First, a literature review tells you how much has already been done in this area. For example, if you are interested in carrying out a study on the portrayal of gender stereotypes in the media, it is important for you to know that you are going to be delving into an area that has been heavily researched for decades. There are literally millions of previous studies on the gender stereotypes in movies, on television, in magazines, and on the internet. In this case, your research question would not be exploratory in nature. One of your next steps with this topic would be to narrow your focus (e.g., perhaps you are more interested in male stereotypes portrayed in magazine advertisements).

- Second, a literature review helps familiarize you with what is already known in the area. Continuing with an interest in stereotyped depictions of males, the literature can help you learn more about the construction of masculinity and how the male body is depicted in advertising. For example, Mishkind, Rodin, Silberstein, & Striegel-Moore (1986) note that advertising has increasingly come to celebrate a young, lean, and highly muscular body. This helps you choose an area that most interests you and that you can build upon with your own research (or that you can identify for an area of future research).

- Third, a literature review helps you understand the debates and main points of interest within an area of study. Existing literature can inform you about how the portrayal of gender stereotypes in the media can lead people to become dissatisfied with their body image or engage in extreme practices and measures designed to obtain an ideal body image (e.g., dieting, fitness, cosmetic surgery). The literature can also help you understand similarities and differences in the ways in which men and women are portrayed, or how depictions of men have changed over time. These considerations may further shape the direction you elect to take with a current or future research project.

- Fourth, a literature review highlights what still needs to be done in an area of interest. By examining previous research, you can find out researchers’ suggestions for additional studies, where replications would be helpful, or areas that still need to be addressed. The discussion section at the end of most academic articles typically includes a few sentences that explicitly address how the current study could have been improved upon and/or point out a direction for future research. This is where you will obtain a sense of how you could design a study that builds on the existing literature but also contributes something new.

- Lastly, a literature review can help you define important theories and concepts as well as establish guidelines for how you will need to carry out your own study. For example, if you wish to clarify how male bodies are shown in magazine advertisements, it would be practical to locate examples by other researchers that have already established standard ways to describe and code the body of a central character in an advertisement appearing in magazines.

Research on the Net

Research is a conversation

As the following video illustrates, when you are tasked with coming up with a research question, it is important to remember that you are entering into a discussion with other academics who have come before you.

Research is a Conversation by UNLV University Libraries is licensed under CC BY-NC. [Video transcript – See Appendix D 2.1]

Test Yourself

In what ways is a literature review essential in the development of a research question?

LOCATING RELEVANT LITERATURE

Resist the temptation to simply search the public internet with your preferred browser for any available resources you can find on your topic of interest. Search engines like Google prioritize links that are from paid sponsors, so the resources that appear first are likely not the most relevant or even appropriate references for your area of interest. Meanwhile, many of the research articles you find using a search engine like Google are behind a paywall requiring that you pay to read more relevant content published by academic publishers. In addition to commercial interests, the public internet also suffers from a lack of quality control; the information you glean from web pages you find on the internet can be obsolete, and worse, fraught with errors.

The best sources of information for a literature review include periodicals, books, and book chapters located in or accessed through a library in a post-secondary institution. You can probably browse an online catalogue system for your post-secondary institution’s library from any computer, if you can access the internet and you are officially registered as a student.

Searching for Books

Books are especially useful when researching specific theories, research methodologies, and the historic context of a topic. Sometimes edited volumes of books contain short research papers written by different authors, which can also be useful when conducting academic research. The search engine on your library’s home page is where you can find books (including eBooks). If you know the title of the book you are looking for, simply type the title into the search box. Putting the title in quotes (e.g., “The Sociology of Childhood and Youth in Canada”) will locate that exact title in the results if it is available. If you instead want to explore what is out there on your topic, enter some relevant keywords. In library databases you will want to put an AND between each different keyword that you search for. For example, if you try searching for a book using the combined keywords male AND stereotypes, you will probably locate a list of starting resources. If there are more than 50 books on this topic, you might try male AND stereotypes AND media to narrow your search a bit further. You can also search for words with similar meanings by putting an OR between the terms that you use in brackets, for instance, (male OR masculine OR masculinity) AND stereotypes AND media. After doing a search, most library catalogues will give you options to the left of your results to limit to just books or eBooks, as well as limiting by publication date and to books on general subject areas.

Searching for Periodicals

Periodicals (including magazines, newspapers, and scholarly journals) are publications that contain articles written by different authors. Periodicals are released periodically at regular intervals such as daily, weekly, monthly, semi-annually, or annually. Popular press periodicals (e.g., Maclean’s, Reader’s Digest, newspapers, and news websites) contain articles that are less scientific and more general-interest focused than scholarly articles published in peer-reviewed periodicals. Scholarly journals published by academic and professional organizations (e.g., universities) are the form of periodical most often cited by your instructors as credible sources for you to use in writing essays and research reports. Scholarly journals contain articles on basic research authored by academics and researchers with expertise in their respective areas. Articles found in scholarly journals have undergone considerable scrutiny in a competitive selection process that rests on peer review and evaluation prior to publication. This helps to ensure that only up-to-date, high-quality research based on sound practices makes it to the publication stage. Examples of Canadian sociological periodicals include the Canadian Journal of Sociology and the Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology. Note that there are hundreds of periodicals spanning a range of related disciplines (e.g., Canadian Journal of Criminology, Canadian Journal of Economics, Canadian Journal of Political Science, and Canadian Psychology) and more specialized topics (e.g., Sex Roles, Child Abuse and Neglect, Contemporary Drug Problems, Educational Gerontology).

Similar to books, in many cases, you can access journals online using the search box on a university library’s homepage or through a database available on a library’s website. If an article is available in “full text,” you can usually download the entire article onto a storage device, so you can later retrieve it for further reading. Comprehensive databases for locating articles on research in the social sciences include Social Sciences Citation Index (part of Web of Science), Academic Search Complete, PsychINFO, SocINDEX, Sociological Abstracts, Criminal Justice Abstracts, and Anthropology Plus. For example, Academic Search Complete is dubbed one of the most comprehensive multidiscipline full-text databases, containing 5,812 full-text journals and magazines on a range of subjects, including psychology, religion, and philosophy (EBSCO Information Services, 2024).

Searching for Government Information

Depending on your research topic, you may find it helpful to reference research findings and statistics provided by governments. Governments at all levels hire researchers to conduct research on a range of topics to help inform public policy and address societal issues. This is one case where you will have to search for information that is available publicly on the internet. Websites like Statistics Canada and Government of Canada Publications contain a lot of content, however, and can be difficult to search. One strategy that can help with this is to perform a site search using Google. Simply enter site: into Google followed by the domain of the website you would like to search along with relevant keywords to locate information on that site containing those words. For instance, site:statcan.gc.ca affordable housing will locate statistics and analysis on housing needs available through Statistics Canada.

Research in Action

Fact Checking and Source Evaluation

It is not enough to simply locate sources of information on an area of interest and assume that you have appropriate materials for learning about the area of interest. While academic journals undergo a peer-review process that helps to provide a check on the quality, accuracy, and currency of the published materials, the internet has little or no quality control. If you use the internet to find sources of information, such as webpages with links to various articles and other resources, it is important to evaluate that information before using it to inform your research.

SIFT & PICK

Librarians at MacEwan University Library (2023) suggest you assess the quality of information you find through this SIFT and PICK strategy:

|

|

Review the Library’s SIFT and PICK handout [PDF] to learn more.

AFP Canada

AFP Fact Check is a department within a larger news agency called Agence France-Press (AFP) dedicated to verifying and providing accurate news coverage. Here, you can find trending stories and search for topics such as “vaccination” to locate the most recent forms of misinformation about the Covid-19 vaccine reported as news. Visit AFP Canada for exclusively Canadian coverage.

Test Yourself

- What are the best sources of information for a literature review?

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- Outline the main assumptions of positivist, interpretative, critical, and pragmatic paradigms.

The positivist paradigm emphasizes objectivity and the importance of discovering truth using empirical methods. The interpretive paradigm stresses the importance of subjective understanding and discovering meaning as it exists for the people experiencing it. The critical paradigm focuses on the role of power in the creation of knowledge. The pragmatic paradigm begins with a research problem and determines a course of action for studying it based on what seems most appropriate given that research problem. - Explain why decolonization is necessary for learning about Indigenous knowledges.

For Indigenous knowledges to be derived from Indigenous sources in an authentic and respectful manner, those who have suffered colonization need to be given the space to communicate on their own terms from their frames of reference, as opposed to trying to obtain information via research methods that are based on Euro-Western influences. - Define and differentiate between theoretical frameworks and theories.

Theoretical frameworks are perspectives based on core assumptions that provide a foundation for examining the social world at different levels. For example, theoretical frameworks at the macro level tend to focus on broader social forces, while those at the micro level emphasize individual experiences. Theories develop from theoretical perspectives, and they include propositions that are intended to explain a fact or phenomenon of interest. - Distinguish between deductive and inductive reasoning and explain how the role of theory differs in qualitative and quantitative research.

Deductive reasoning is a top-down, theory-driven approach that concludes with generalizations based on research findings. Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach that begins with observations and typically ends with theory construction. Inductive approaches to reasoning guide qualitative research processes, while deductive approaches guide the stages of quantitative research. Theory tends to be the starting point for quantitative research, while it is interspersed throughout and emphasized more in the later stages of qualitative research. - Formulate social research questions.

Based on a broad area of interest and a careful literature review, a researcher eventually shapes a research interest into a social research question, which is a question about the social world that is answered through the collection and analysis of data. For example, a researcher might begin with an interest in gender that develops into an examination of the effects of body size on income for male and female workers, as demonstrated earlier in the chapter. - Explain the importance of a literature review.

A literature review is the starting point for formulating social research questions. A literature review helps to identify what is already known about and still needs to be done in an area of interest. A literature review also points out debates and issues in an area of interest, along with the most relevant concepts and means for going about studying the issue in more depth. - Locate appropriate literature and evaluate sources of information found on the internet.

Appropriate literature sources include periodicals, books, and government documents, most of which can be accessed online through the library at post-secondary institutions. You should evaluate the quality of information gleaned from websites prior to using that information as a primary source in a literature review. Evaluating information on the internet generally takes the form of asking questions that centre on the source, timeliness, accuracy, and relevance of the site. For example, in assessing accuracy, you can ask “Is the information free of spelling, grammatical, and technical errors?” and “Where did the information come from?”

RESEARCH REFLECTION

- Read Margaret Kovach’s (2018) chapter titled Doing Indigenous methodologies: A letter to a research class in N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 108–150). Sage. Based on your reading, explain why the author claims it is not possible to do Indigenous methodologies. Also note the ways in which Indigenous methodologies are relational in nature.

- Identify a general area of interest to you. Within that area of interest, develop two social research questions—one that implies an exploratory purpose and one that implies an explanatory purpose. Which paradigm introduced at the beginning of the chapter do you think best represents the research questions you developed? Explain why this is the case.

- In what ways is an article found in a scholarly journal likely to be more appropriate as a reference source for a research topic than one located using a search engine such as Bing or Google?

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE

Objective: To assess information on the internet

Directions:

- Use Google to locate a website that contains relevant information on a topic of interest.

- Assess the website and associated resources using the following 10 questions:

- Who created the site and what are their credentials?

- What are the qualifications of authors associated with the site?

- Is it possible to verify the accuracy of any of the claims made on this site?

- Is an educational purpose for this site evident?

- Is the site objective (or free from bias)?

- Is the site free of advertisements?

- Can you tell when the site was created?

- Was the site updated recently?

- Are there properly cited references on the site?

- Are there any errors on site (e.g., spelling, grammatical)?

- What rating would you give this site out of 100, if 100 percent is “perfect” and 0 stands for “without any merit.” Explain why you think the site deserves this rating based on the questions listed above.

RESEARCH RESOURCES

- To learn more about social theorists and the underpinnings of social theory, refer to Ritzer, G., and Stepnisky, J. (2021). Sociological theory (11th ed.). Sage.

- For an introduction to Indigenous ways of knowing, as well as historical and contemporary issues involving Canada’s First Peoples, refer to Belanger, Y. D. and Hanrahan, M. (2022). Ways of knowing: An introduction to Indigenous studies in Canada (4th ed.). Top Hat.

- To learn about decolonizing strategies and the potential for Indigenizing education, read Cote-Meek, S., and Moeke-Pickering, T. (2020). Decolonizing and Indigenizing education in Canada. Canadian Scholars Press.

- To learn how Indigenous knowledge structures inform research conducted by Indigenous scholars, see Kovach, M. (2021). Indigenous methodologies: Characteristics, conversations and contexts. University of Toronto Press.

- For more information on feminist inquiry, critical race theory, critical disabilities studies, and queer theory , refer to The Sage handbook of qualitative research (6th ed.) (2024), edited by Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln, Michael D. Giardina, and Gaile S. Cannella. ↵

- The sharing circle was part of a larger community-based project carried out by Reith Charlesworth during the winter of 2016, under the supervision of Brianna Olson, an Anishnaabe (First Nations) Métis woman/social worker who was iHuman’s program manager, and Dr. Alissa Overend, Reith’s research mentor at MacEwan University. Dr. Diane Symbaluk taught the foundational research methods course for this project in the fall of 2015 and set up/oversaw student placements as the faculty coordinator for the 2015–2016 calendar year. ↵

- An in-depth discussion of feminist perspectives is beyond the scope of this book. To learn about feminist standpoints and their relationships to research methodology, I recommend The handbook of feminist research: Theory and praxis (2nd ed.), edited by Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber (2012). For insight into conceptions of power, refer to The Power of Feminist Theory: Domination, Resistance, Solidarity, by Amy Allen (1999). ↵

A theoretical perspective including a set of assumptions about reality that guide research questions.

A worldview that upholds the importance of discovering truth through direct experience using empirical methods.

A worldview that rests on the assumption that reality is socially constructed and must be understood from the perspective of those experiencing it.

A worldview that is critical of paradigms that fail to acknowledge the role of power in the creation of knowledge and that is aimed at bringing about empowering change.

A worldview that rests on the assumption that reality is best understood in terms of the practical consequences of actions undertaken to solve problems.

Diverse learning processes that come from living intimately with the land and working with the resources surrounding the land base and the relationships that it has fostered over time and place.

A process of conducting research in such a way that the worldview of those who have suffered a long history of oppression and marginalization are given space to communicate from their frames of reference.

A perspective based on core assumptions.

The level of broader social forces.

The level of individual experiences and choices.

A set of propositions intended to explain a fact or phenomenon.

A theory-driven approach that typically concludes with empirical generalizations based on research findings.

A testable statement that contains at least two variables.

A categorical concept for properties of people or events that can differ and change.

A bottom-up approach beginning with observations and ending with the discovery of patterns and themes informed by theory.

Theory discovered from the systematic observation and analysis of data.

A question about the social world that is answered through the collection and analysis of first-hand, verifiable, empirical data.

Publications that contain articles written by different authors and are released at regular intervals.