Chapter 4: Research Design and Measurement

In any discussion about improving measurement, it is important to begin with basic questions. What exactly are we trying to measure, and why?

— Christine Bachrach, 2007, p. 435

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

- Describe the main components of a research design.

- Explain what conceptualization and operationalization processes entail.

- Explain how the purpose of a variable is directly related to how it is measured in research.

- Outline the main techniques used to assess reliability and validity.

- Distinguish between random and systematic errors.

- Explain how rigour is achieved in qualitative research.

INTRODUCTION

After carefully considering research foundations, the importance of theory, and the ethics involving research with humans, you are almost ready to delve into the techniques used for obtaining answers to social research questions. But before you can start collecting data, you need to develop a research plan that outlines who or what it is you are studying and how you will go about measuring and evaluating the attitudes, behaviours, or processes that you want to learn more about.

MAIN COMPONENTS OF A RESEARCH DESIGN

Linked to a specific research question, a research design “is the plan or blueprint for a study and includes the who, what, where, when, why, and how of an investigation” (Hagan, 2021, Chapter 3, para 1.). Beginning with the “who,” researchers in the social sciences most often study people, so individuals are usually the focus of investigation, called the unit of analysis. Individuals are often studied as part of a collective or group. For example, the unit of analysis could be students, employees, single-parent-headed families, low-income earners, or some other group of interest. Researchers also compare groups of individuals along particular variables of interest, such as a sample of individuals with less than a high school education versus those who have a grade 12 diploma, single- versus dual-income families, or patients who completed a treatment program versus ones who dropped out. Social institutions and organizations that guide individuals and groups can also be the units of analysis for research, such as the university you are attending, a not-for-profit agency such as the Canadian Red Cross, or a healthcare organization such as the Canadian Medical Association. Finally, social researchers are sometimes interested in artifacts created by people rather than people themselves. For example, researchers might examine news articles, television shows, motion pictures, profiles on an online dating site, YouTube videos, Facebook postings, or X tweets.

The “what” component of research design refers to whatever is specifically examined and measured in a study, such as attitudes, beliefs, views, behaviours, outcomes, and/or processes. The measured component is usually referred to as the “unit of observation” since this is what the data is collected on. For example, a researcher might be interested in factors affecting instructors’ views on published ratings of instruction. Instructors at a university who take part in the study constitute the unit of analysis from whom the views on published ratings are obtained (i.e., the more specific focus of the research that comprises the data). Similarly, a researcher might be interested in dating preferences of individuals who use online matchmaking sites such as eharmony or EliteSingles. The individuals seeking dates online are the units of analysis, while their posted profiles containing the characteristics of interest in the study are the units of observation.

The “where” pertains to the location for a study. The possibilities are endless, from research conducted first-hand in the field to studies conducted in a public setting such as a coffee shop or a private one such as the home of a participant. The location for a study is closely linked to the unit of analysis since the researcher often needs to go to the individuals, groups, or organizations to collect information from them or about them. For example, a researcher interested in interviewing couples who met online might set up appointments to visit dating couples in restaurants or coffee shops near to where the couples reside, at the discretion of the participants. Alternatively, a researcher interested in online dating relationships might choose to gather information in a virtual environment by posting a survey on the internet.

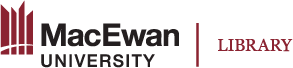

The “when” relates to an important time consideration in the research design. Some studies are conducted once at a single point in time, and others are carried out at multiple points over time. Most often, when social researchers carry out a study, it takes place at a single point in time or within a single time frame, such as when a researcher develops a questionnaire about internet dating and administers it to a group of people attending a singles’ social function. This is called cross-sectional research because the study is made up of a cross-section of the dating population taken at a point in time, like taking a photo that captures a person or group at a single point in time. Alternatively, social researchers sometimes study individuals or groups at multiple points in time using what is called longitudinal research. For example, a sample of dating couples might be surveyed shortly after they meet and again after dating for one year to capture their initial viewpoints and to see how their perceptions change once they get to know each other better. Four longitudinal designs are discussed below.

A panel study is a longitudinal study in which a researcher observes the same people, group, or organization at multiple points in time. A new phase of a large-scale panel study called Alberta’s Tomorrow Project was launched in 2017 to learn more about the causes of cancer. The study, active since 2000, includes 55,000 cancer-free Albertans (Alberta’s Tomorrow Project, 2024b). Researchers from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project collect information on participants’ health and lifestyle through surveys and the occasional collection of other specimens, such as blood samples. Going back to the dating example, by collecting information on the same dating couples at various intervals, a researcher could use a panel study to examine how relations evolve or change over time.

A cohort study is like a panel study, except, rather than focusing on the same people, it focuses on comparable people over time. “Comparable” refers to a general category of people who are deemed to share a similar life experience in a specified period. The most common example of this is a birth cohort. Think about the classmates you went through school with. Although there were individual differences between you and your classmates, you also shared some common life events, such as the music that topped the charts at that time, the clothing fads and hairstyles, and the political events that occurred during that era. Following the earlier example, a researcher might include people who met online and married their dating partner in 2020 as Covid-19 was unfolding as a unit of analysis. Several couples might be studied in 2020 shortly after they were married, several other couples who also married in 2020 might be studied in 2021, another group in 2022, another group in 2023, and so on over a period of five years.

A time-series study is a longitudinal study in which a researcher examines different people at multiple points in time. Every year, Statistics Canada gathers information from thousands of Canadians using what is called the General Social Survey. Although the participants are different each time, similar forms of information are gathered over time to detect patterns and trends. For example, we can readily discern that Canadians today are delaying marriage (i.e., getting married for the first time at a later age) and they are having fewer children relative to 20 years ago. Going back to the online dating example used throughout this section, a researcher might use a time-series study in order gather information from new dating couples at an online site each year for five years. Looking at the data over time, a researcher would be able to determine if there are changes in the overall profiles of online daters at that site. For example, the use of the site might be increasing for groups such as highly educated women or single individuals over the age of 60 years.

Lastly, a case study is a research method in which a researcher focuses on a small number of individuals or even a single person over an extended period. You’ll learn more about this method in Chapter 11. For now, you can think of a case study as a highly detailed study of a single person, group, or organization over time. For example, a researcher might study an alcoholic to better understand the progression of the disease over time, or a researcher might join a subculture, such as a Magic card club that meets every Friday night, to gain an insider’s perspective of the group. Similarly, a researcher could examine the experiences of a frequent online dater over time to get a sense of how online dating works at various sites. See figure 4.1 for an overview of time considerations in relation to units of analysis.

Research in Action

Longitudinal Panel Study on Smokers’ Perceptions of Health Risks

Cho and colleagues (2018) examined changes in smokers’ perceptions about health risks following amendments to warning labels on cigarette packages using a longitudinal panel study. Four thousand six hundred and twenty-one smokers from Canada, Australia, Mexico, and the United States were surveyed every four months for a total of five times to determine if their knowledge of health risks increased after toxic constituents were added to pictorial health warning labels. Results showed that knowledge of toxic constituents such as cyanide and benzene increased over time and was associated with a stronger perceived risk of vulnerability to smoking-related diseases, including bladder cancer and blindness, for participants in Canada, Australia, and Mexico, but not the United States (Cho et al., 2018).

In addition to the time dimension, a research design also includes the “why” and the “how” plan for a study. “Why” relates to the purpose of a study as discussed in chapter 1. A study on internet dating could be focused on exploring ways in which people represent themselves in posted profiles; describing who uses internet dating sites; explaining the importance of including certain types of information, such as appearance or personality factors, for attracting dates; or evaluating the effectiveness of a given site in matching suitable partners. The nature of the study really depends on the interests of the researcher and the nature of the issue itself.

“How” refers to the specific method or methods used to gather the data examined in a study. With an interest in the merit of including certain items in a dating profile, a researcher might opt for an experimental design to explain, for example, whether certain characteristics in posted dating profiles are better than others for eliciting potential dates (see chapter 6 for a discussion of different types of experiments). An experiment is a special type of quantitative research design in which a researcher changes or alters something to see what effect it has. In the dating example, an experimenter might compare the number of responses to two profiles posted at an internet dating site. If the profiles are identical except for one trait—for example, one profile might contain an additional statement saying the person has a great sense of humour—it would be possible to determine the importance of that trait in attracting potential partners.

Recall from chapter 1 that the specific methods or techniques differ depending on whether a researcher adopts a qualitative or quantitative orientation, and the approach itself links back to the research interest. A researcher interested in learning more about why people make dates online or how people define themselves online is more apt to use a qualitative approach. Qualitative researchers tend to engage in research that seeks to better understand or explain some phenomenon using field research and in-depth interviews, as well as strategies involving discourse analyses and content analyses that can be used to help to uncover meaning. Regardless of the approach taken and specific methods used, all researchers must work through various design considerations and measurement issues in their quest to carry out scientific research. Similarly, both qualitative and quantitative researchers undertake a process of conceptualization and measurement—it just occurs differently and at different stages within the overall research process, as discussed in the next section.

Test Yourself

- What does a research design inform us about?

- What is the main difference between cross-sectional and longitudinal research?

- What is the name for research on the same unit of analysis carried out at multiple points in time?

- In what ways will a quantitative research design differ from a qualitative one?

CONCEPTUALIZATION AND OPERATIONALIZATION

Researchers in the social sciences frequently study social issues, social conditions, and social problems that affect individuals, such as environmental disasters, legal policy, crime, healthcare, poverty, divorce, marriage, or growing social inequality between the rich and poor, within a conceptual framework. Their quest is to explore, describe, explain, or evaluate the experiences of individuals or groups. A conceptual framework is the more concentrated area of interest used to study the social issue or problem, which includes the main objects, events, or ideas, along with the relevant theories that spell out relationships. Terms like family or crime are broad concepts that refer to abstract mental representations used to signify important elements of our social world. Concepts are very important because they form the basis of social theory and research in the social sciences. However, as often-abstract representations, concepts like family can be vague since they mean different things to different people. Consider what the concept of family means to you. Does your notion of a family include aunts and uncles or second cousins? What about close friends? How about pets? People have very divergent views about what a family is or is not. The concept of family also has very different meanings depending on the context in which it is applied. For example, there are rules about who is or is not considered eligible to be sponsored under family status for potential immigration to Canada, or who may or may not be deemed family for visitation rights involving prisoners under the supervision of the Correctional Service of Canada. Because concepts are broad notions that can take on various meanings, researchers need to carefully define the concepts (or constructs) that underlie their research interests as part of the conceptualization and operationalization process.

Conceptualization, in research, is the process where a researcher explains what a concept or construct means in terms of a research project. For example, a researcher studying the impact of education cutbacks on the family, with an interest in the negative implications for children, might adopt the broad conceptualization of family provided by Statistics Canada (2021):

Census family is defined as a married couple and the children, if any, of either and/or both spouses; a couple living common law and the children, if any, of either and/or both partners; or a parent of any marital status in a one-parent family with at least one child living in the same dwelling and that child or those children. All members of a particular census family live in the same dwelling. Children may be biological or adopted children regardless of their age or marital status as long as they live in the dwelling and do not have their own married spouse, common-law partner or child living in the dwelling. Grandchildren living with their grandparent(s) but with no parents present also constitute a census family. (para. 1)

Conceptualization is essential since it helps us understand what is or is not being examined in a study. For example, based on the conceptualization provided above, children being raised by their grandparents or living in homes headed by single parents would be included in the study, but they might have otherwise been missed if a more traditional definition of family were employed.

The term concept is often used interchangeably with a similar term, construct. Both refer to mental abstractions; however, concepts derive from tangible or factual observations (e.g., a family exists), while constructs are more hypothetical or “constructed” ideas that are part of our thinking but do not exist in readily observable forms (e.g., love, honesty, intelligence, motivation). While we can readily measure and observe crime through different acts that are deemed criminal (the concept crime), we infer intelligence through measures such as test scores (the construct intelligence). Both concepts and constructs are the basis of theories and are integral components underlying social research. Like concepts, constructs undergo a process of conceptualization when they are used in research. Suppose a researcher is interested in studying social inequality, which we commonly understand to mean differences among groups of people in terms of their access to resources such as education or healthcare. We know some people can afford private schools, while others cannot. We understand that healthcare benefits differ depending on factors such as how old a person is, how much one pays for a health plan, what type of job one has, and where one lives. Social inequality is a construct that conjures up a wide range of examples and notions. To examine social inequality in a specific study, a researcher might opt to use personal finances as an indicator of social inequality. An indicator is “a measurable quantity which ‘stands in’ or substitutes, in some sense, for something less readily measurable” (Sapsford, 2006, para. 1). Personal finances can be further specified as employment income, since most of the working population is able to state how much they earn in dollars.

Note that in the case of employment income, people earn a certain amount of money (i.e., gross pay), but they receive a different amount as their take-home pay after taxes and various deductions come off (i.e., net pay). The process we use to examine with precision the progression of taking an abstract construct, such as social inequality, and conceptualizing it into something tangible, such as net income, is known as operationalization. Operationalization is the process whereby a concept or construct is defined so precisely that it can be measured. In this example, financial wealth was operationalized as net yearly employment income in dollars. Note that once a construct such as social inequality has been clarified as financial wealth and then measured in net yearly income dollars, we are now working with a variable, since net yearly income is something that can change and differ between people. Quantitative researchers examine variables. A researcher interested in implications of social inequality might test the hypothesis that among individuals who work full time, those with low net yearly incomes will report poorer health compared to people with high net yearly incomes. In this example, health (the second variable) might be operationalized into the self-reported ratings of very poor, poor, fair, good, or very good.

In contrast, qualitative researchers tend to define concepts based on the users’ own frameworks. Qualitative researchers are less concerned with proving that certain variables affect the individual. Instead, they are more concerned with how individuals make sense of their own social situations and what the broader social factors are for such framing.

Research in Action

Online Dating and Variables

Students routinely have difficulty understanding what variables are, let alone how to explore research questions that contain them. A starting point is to examine what is contained in a typical “profile” posted on any internet dating site, such as EliteSingles or eharmony. Registered members list certain attributes they feel best describe themselves and that may also be helpful in attracting a compatible dating partner, such as their age, physical features, and certain personality traits. For example, someone might advertise as a single male, 29 years of age, 5’11” tall, in great shape, with a good sense of humour, seeking men between the ages of 25 and 35 for friendship. These attributes are variables; many that are routinely used in social research! Variables are often defined using categories. For example, the word single refers to a category of the variable “marital status.” Marital status is a variable since it is a property that can differ between individuals and change over time, as in single, common-law, married, separated, widowed, or divorced. Other variables listed on dating sites include age (in years), gender and preference (e.g., man interested in men), height (in feet and inches), body type (slim, fit, average), eye colour (e.g., green, blue, or brown), and astrological sign (e.g., Virgo, Libra, Scorpio). Even the purpose or intent of the posting constitutes a variable, since a person may state whether they are seeking fun, friendship, dating, or a long-term relationship.

Test Yourself

- What is a concept? Provide an example of one that is of interest to social researchers.

- Why is conceptualization important to researchers?

- What is an indicator? Provide an example of one that could be used in a study on aggression.

- What are three variables you could examine in a study of online dating relationships?

MEASURING VARIABLES

Now that you better appreciate what is meant by a variable, you can also start to see how variables are operationalized in different ways. Some variables are numerical, such as age or income, while others pertain more to categories and descriptors, such as marital status or perceived health status. Decisions made about how to clarify a construct such as health have important implications for other stages of the research process, including what kind of analyses are possible and what kind of interpretations can be made. For example, the categories for the self-reported health variable described above can tell us whether someone perceives their health to be better or worse than someone else’s (e.g., “very good” is better than “good,” while “fair” is worse than “good” but better than “poor”). However, from how this variable is measured, we are unable to ascertain how much worse or how much better someone’s health is relative to another.

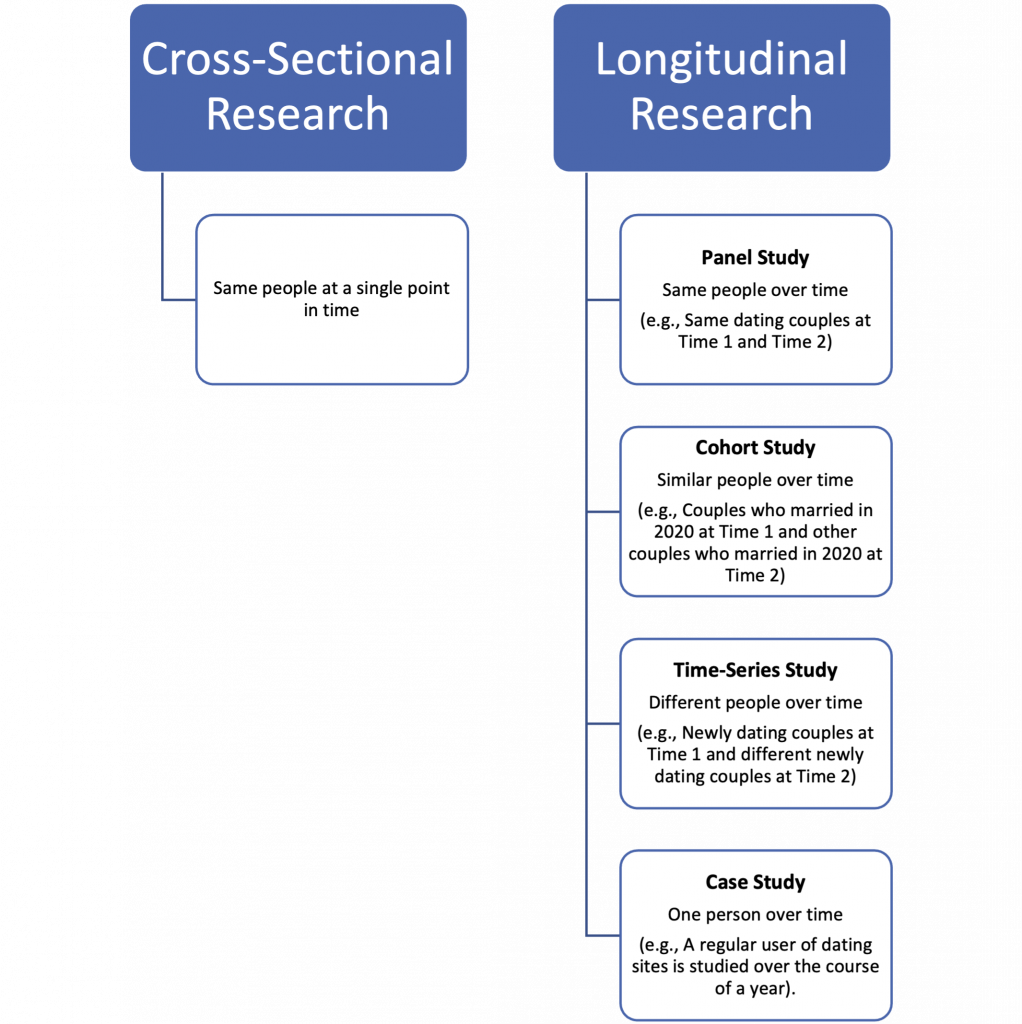

Levels of Measurement

Variables mean different things and can be used in different ways, depending upon on how they are measured. At the lowest level, called the nominal level, we can classify or label cases, such as persons, according to marital status, eye colour, religion, or the presence of children. These are all qualitative variables. Even if we assign numbers to the categories for marital status, where 1 = single, 2 = common-law, 3 = married, 4 = separated, 5 = widowed, and 6 = divorced, we have not quantified the variable. This is because the numbers serve only to identify the categories so that a 6 now represents anyone who is currently “divorced.” The numbers themselves are arbitrary; however, they serve the function of classification, which simply indicates that members of one category are different from another category.

At the next level of measurement, called the ordinal level, we can classify and order categories of the variables of interest, such as people’s perceived health into levels, job satisfaction into ratings, or prestige into rankings. Note that these variables are measured as more or less, or higher or lower amounts, of some dimension of interest. The variable health, then, measured as very good, good, fair, poor, and very poor, is an ordered variable since we know that very good is higher than good and therefore indicates better health. However, as noted earlier, we cannot determine precisely what that means in terms of how much healthier someone is who reports very good health. Ordinal variables are also qualitative in nature.

At the next highest level of measurement, called the interval level, we can classify, order, and examine differences between the categories of the variables of interest This is possible because the assigned scores include equal intervals between categories. For example, with temperature as a main variable, we know that 28°C is exactly one degree higher than 27°C, which is 7 degrees higher than 20°C, and so on.

Statisticians sometimes make a further distinction between an interval and ratio level of measurement. Both levels include meaningful distance between categories, as well as the properties from the lower levels. However, a true zero only exists at the ratio level of measurement constituting the additional property. In the case of temperature, 0°C cannot be taken to mean the absence of temperature (an absolute or true zero). At the ratio level, however, there is a true zero in the case of time, where a stopwatch can count down from two minutes to zero, and zero indicates no time left. Most variables that include the property of score assignment have a true zero. One way to determine if a variable is measured at the ratio level is to consider if its categories can adhere to the logic of “twice as.” For example, an assessment variable where a person can achieve twice the score of someone else or net employment income where one employee can earn twice that of another are both measured at the ratio level. Interval- and ratio-level variables are quantitative, and they are amenable to statistical analyses such as tests for associations between variables. The properties of each level of measurement are summarized in figure 4.2.

Activity: Sorting Levels of Measurement

Indexes versus Scales

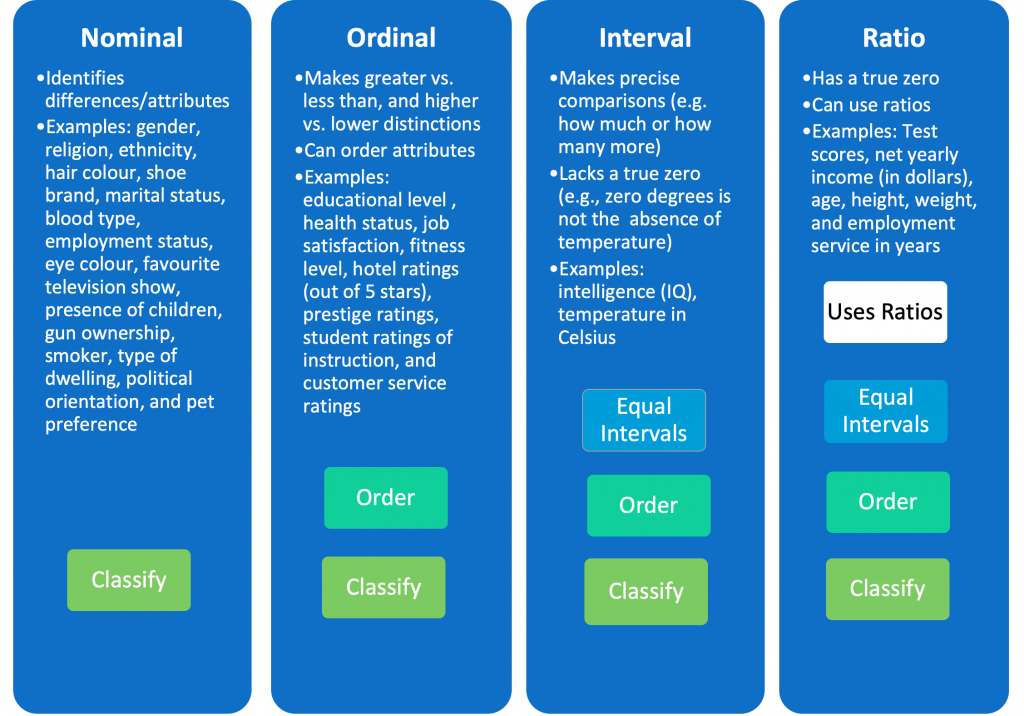

Instead of using the response to a single statement as a measure of some construct, indexes and scales combine several responses together to create a composite measure of a construct. An index is a composite measure of a construct comprising several different indicators that produce a shared outcome (DeVellis & Thorpe, 2021). For example, in a study on gambling, Wood and Williams (2007) examined the extent to which internet gamblers manifest a “propensity for problem gambling” (i.e., the outcome). The propensity for problem gambling was assessed using nine items composing the Canadian Problem Gambling Index (CPGI). The CPGI consists of a series of nine questions, which follow prompts to consider only the preceding 12 months, including “Thinking about the last 12 months … have you bet more than you could really afford to lose?”; “Still thinking about the last 12 months, have you needed to gamble with larger amounts of money to get the same feeling of excitement?”; and “When you gambled, did you go back another day to try and win back the money you lost?” The response categories for all nine items are sometimes (awarded a score of 1), most of the time (awarded a score of 2), almost always (scored as 3), or don’t know (scored as zero). The scores are added up for the nine items, generating an overall score for propensity for problem gambling that ranges between 0 and 27, where 0 = non-problem gamblers, 1–2 = a low-risk for problem gambling, 3–7 = a moderate risk, and 8 or more = problem gamblers (Ferris & Wynne, 2001). Although the index has several items, they all independently measure the same thing: the propensity to become a problem gambler. And while there are expected relationships between the items—for instance, spending more than one can afford to lose is assumed to be associated with needing to gamble with larger amounts of money to get the same feeling of excitement—the indicators are not derived from a single cause (DeVellis & Thorpe, 2021). That is, a person may gamble more than they can afford to lose due to a belief in luck, while the same person might need to gamble larger amounts due to a thrill-seeking tendency. Regardless of their origins, the indicators result in a common outcome: the tendency to become a problem gambler. The higher the overall score on an index, the more of that trait or propensity the respondent has.

In contrast, a scale is a composite measure of a construct consisting of several different indicators that stem from a common cause (DeVellis & Thorpe 2021). For example, the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire—Revised (EPQR) is a 48-item questionnaire designed to measure an individual’s personality (the construct) via extroversion and neuroticism (Eysenck et al., 1985). Extroversion and neuroticism are two underlying potential causes for certain behavioural tendencies. Extroversion is the propensity to direct one’s attention outward toward the environment. Thus, extroverts tend to be people who are outgoing or talkative. Sample yes/no forced-choice items on the EPQR measuring extroversion include the statements “Are you a talkative person?”; “Do you usually take the initiative in making new friends?”; and “Do other people think of you as being very lively?” Neuroticism refers to emotional stability. For example, a neurotic person is someone who worries excessively or who might be described as moody. Sample questions include “Does your mood often go up and down?”; “Are you an irritable person?”; and “Are you a worrier?”

Note that there are some similarities between indexes and scales and that these terms are often used interchangeably (albeit incorrectly) in research! Both indexes and scales measure constructs—for example, dimensions of personality, risk for problem gambling—using nominal variables with categories such as yes/no and presence/absence or ordinal variables depicting intensity such as very dissatisfied or dissatisfied. In addition, both are composite measures, meaning they are made up of multiple items. However, there are also some important differences (see figure 4.3).

While an index is always an accumulation of individual scores based on items that have no expected common cause, a scale is based on the assignment of scores to items that are believed to derive from a common cause. In addition, scales often comprise items that have logical relationships between them. Namely, someone who indicates on EPQR that they “always take the initiative in making new friends” and “always get a party going” is also very likely to “enjoy meeting new people,” but is very unlikely to be “mostly quiet when with other people.” In addition, specific items in a scale can indicate varying intensity or magnitude of a construct in a manner that is accounted for by the scoring. For example, the Bogardus social distance scale measures respondents’ willingness to participate with members of other racial and ethnic groups (Bogardus, 1933). The items in the scale have different intensity, meaning certain items show more unwillingness to participate with members of other groups than others. For example, an affirmative response to the item “I would be willing to marry outside group members” indicates very low social distance (akin to low prejudice) and scores 1 point, whereas an affirmative response to “I would have (outside group members) merely as speaking acquaintances” scores 5, indicating more prejudice. A scale takes advantage of differences in intensity or the magnitude between indictors of a construct and weights them accordingly when it comes to scoring. In contrast, an index assumes that all items are different but of equal importance.

Sometimes it can be difficult to determine if an instrument is better classified as a scale or an index. For example, the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26) was developed by Garner and Garkfinkel (1979) as a self-report measure designed to help identify those at risk for an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa. Taken together, it can be considered an index since it is based on items that do not have a single underlying cause since eating disorders can result from many different individual causes. Importantly, as required by an index, the indicators are used to derive a composite score for a common outcome (risk of anorexia) by summing up the scores obtained for all 26 independent items. However, the EAT-26 also contains three sub-scales, where certain items can be used to examine dimensions of anorexia that are believed to be the result of dieting, bulimia and food preoccupation, and oral control (common causes).

Test Yourself

- What property distinguishes the ordinal level of measurement from the nominal?

- What are the main properties and functions of the interval level of measurement?

- What special property does the ratio level have that distinguishes it from the interval level of measurement?

- In what ways are indexes and scales similar and different?

CRITERIA FOR ASSESSING MEASUREMENT

Measurement often involves obtaining answers to questions posed by researchers. In some cases, the answers to questions might be very straightforward, as would be your response to the question “How old are you?” But what if you were instead asked, “What is your ethnicity?” Would your answer be singular or plural? Would your answer reflect the country you were born in and/or the one you currently reside in? Did you consider the origin of your biological father, mother, or both parents’ ancestors (e.g., grandparents or great-grandparents)? Did you think about languages you speak other than English or any cultural practices or ceremonies you engage in? Ethnicity is a difficult concept to measure because it has different dimensions; it reflects ancestry in terms of family origin as well as identity in the case of more current personal practices. According to Statistics Canada (2017), if the intent of the study is to examine identity, then a question such as “With which ethnic group do you identify?” is probably the best choice, since it will steer respondents to that dimension by having them focus on how they perceive themselves. To assess whether measures are “good” ones, you can evaluate their reliability and validity.

RELIABILITY

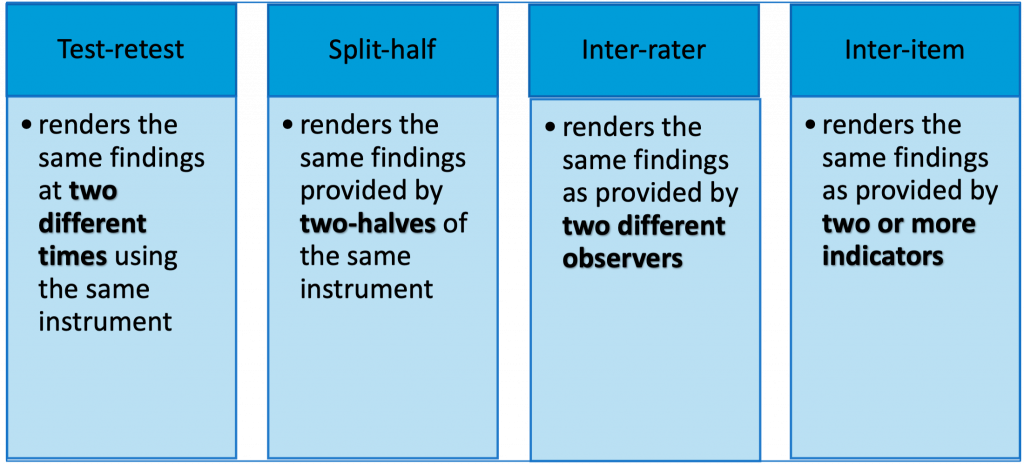

As a quantitative term, reliability refers to the consistency in measurement. A measurement procedure is reliable if it can provide the same data at different points in time, assuming there has been no change in the variable under consideration. For example, a weigh scale is generally considered to be a reliable measure for weight. That is, if a person steps on a scale and records a weight, the person could step off and back on the scale and it should indicate the same weight a second time. Similarly, a watch or a clock—barring the occasional power outage or worn-out battery—is a dependable measure for keeping track of time on a 24-hour cycle (e.g., your alarm wakes you up for work at precisely 6:38 a.m. on weekdays). Finally, a specialized test can provide a reliable measure of a child’s intelligence in the form of an intelligence quotient (IQ). IQ is a numerical score determined using an instrument such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—Fifth Edition (WISC-V), released by Pearson in 2014. The test consists of questions asked of a child by a trained psychologist who records the answers and then calculates scores to determine an overall IQ (Weschler, 2003). IQ is considered a reliable indicator of intelligence because it is stable over time. The average IQ for the general population is 100. A child who obtained an IQ score of 147 on the WISC-V at age eight would be classified as highly gifted. If that same person took an IQ test several years later, the results should also place the person in the highly gifted range. While a child could have a “bad test” day if they felt ill, was distracted, and so on, it is not reasonable to assume that the child guessed his way to a score of 147! Four ways to determine if a measure is reliable or unreliable are discussed below, including test-retest, split-half, inter-rater, and inter-item reliability.

Test-Retest Reliability

Demonstrating that a measure of some phenomenon, such as intelligence, does not change when the same instrument is administered at two different points in time is known as test-retest reliability. Test-retest reliability is usually assessed using the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient (represented by the symbol r). The correlation ranges between 0 and +1.00 or –1.00, representing the degree of association between two variables. The closer the value of r is to +1.00, the greater the degree or strength of the association between the variables. For example, an r of +.80 is higher than one that is +.64, 0 indicates no relationship between the two variables, and 1.00 indicates a perfect relationship. The positive or negative sign indicates the direction of a relationship. A plus sign indicates a positive relationship, where both variables go in the same direction. For example, an r of +.60 for the relationship between education and income tells us that as education increases, so does income. In the case of negative correlations, the variables go in opposite directions, such as an r = –54 for education and prejudice. With increased education, we can expect decreased prejudice.

To evaluate test-retest reliability, the correlation coefficient is denoting the relationship between the same variable measured at time 1 and time 2. The correlation coefficient (also called a reliability coefficient) should have a value of .80 or greater to indicate good reliability (Cozby et al., 2020). Test-retest reliability is especially important for demonstrating the accuracy of new measurement instruments. Currently, the identification of gifted children is largely restricted to outcomes determined by standardized IQ tests administered by psychologists (Pfeiffer et al., 2008). Expensive IQ tests are only funded by the school system for a small fraction of students, usually identified early on as having special needs. This means most students are never tested, and many gifted children are never identified as such. An alternative instrument, the Gifted Rating Scales (GRS), published by PsychCorp/Harcourt Assessment, is based on teacher ratings of various abilities, such as student intellectual ability, academic ability, artistic talent, leadership ability, and motivation. Test-retest reliability coefficients for this assessment tool’s various scales were high, as reported in the test manual. For example, the coefficient for the Academic Ability scale used by teachers on a sample of 160 children aged 12.00 to 13.11 years old and reapplied approximately a week later was .97 (Pfeiffer et al., 2008).

Split-Half Reliability

An obvious critique of test-retest reliability concerns the fact that since participants receive the same test twice or observers provide ratings of the same phenomenon at close intervals in time, the similarity in results could have more to do with memory for the items than the construct of interest. An alternative to the test-retest method that provides a more independent assessment of reliability is the split-half reliability approach. Using this method, a researcher provides exactly half of the items at time 1 (e.g., only the odd-numbered items or a random sample of the questions on a survey) and the remaining half at time 2. In this case, the researcher compares the two halves for their degree of association.

Inter-Rater Reliability

Another way to test for the reliability of a measure is by comparing the results obtained on one instrument provided by two different observers. This is called inter-rater reliability (and interchangeably inter-judge-, inter-coder-, or inter-observer reliability). Inter-rater reliability is the overall percentage of times two raters agree after examining each pair of results. Using the IQ example above, two different teachers would provide assessments of the students on the various indicators of giftedness and then the two sets of responses would be compared. If two different teachers agree most of the time that certain children exhibit signs of giftedness, we can be more confident that the scales are identifying gifted children as opposed to showing the biases of a teacher toward their students.

A statistical test called Cohen’s kappa is usually employed to test inter-rater reliability because it takes into account the percentage of agreement as well as the number of times raters could be expected to agree just by chance alone (Cohen, 1960).[1] Given the conservative nature of this test, Landis and Koch (1977) recommend considering coefficients of between .61 and .80 as substantial and .81 and over as indicative of near-to-perfect agreement. Building on the earlier example, the test manual for the GRS reported an inter-rater reliability of .79 for the academic ability of children aged 6.00 to 9.11 years old, based on the ratings of two different teachers for 152 students (Pfeiffer et al., 2008).

Inter-Item Reliability

Lastly, when researchers use instruments that contain multiple indicators of a single construct, it is also possible to assess inter-item reliability. Inter-item reliability (also called internal-consistency reliability) refers to demonstrated associations among multiple items representing a single construct, such as giftedness. First, there should be close correspondence between items evaluating a single dimension. For example, students who score well above average on an item indicating intellectual ability (e.g., verbal comprehension) should also score well above average on other items making up the intellectual ability scale (e.g., memory, abstract reasoning). The internal consistency of a dimension such as intellectual ability can be assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, a coefficient ranging between 0 and 1.00, which considers how pairs of items relate to one another (co-vary), the variance in the overall measure, and how many items there are (Cronbach, 1951).

In addition, since giftedness is a broad-ranging, multidimensional construct that is usually defined to mean more than just intellectual ability, students who score high on the dimension of intellectual ability should also score high on other dimensions of giftedness, such as academic ability (e.g., math and reading proficiency) and creativity (e.g., novel problem solving). Pfeiffer et al. (2008) reported a correlation coefficient of .95 between intellectual ability and academic ability and one of .88 between intellectual ability and creativity using the GRS. The four approaches for assessing reliability that were discussed in this section are summarized in figure 4.4.

Research on the Net

Inter-Rater Reliability

For more information on inter-rater reliability and what Cohen’s Kappa is and how it is calculated, check out this video by DATAtab: Cohen’s Kappa (Inter-Rater-Reliability)

Test Yourself

- What is reliability? Provide an example of a reliable measure used in everyday life.

- What is the main difference between test-retest reliability and split-half reliability?

- What type of reliability renders the same findings provided by two different observers?

- What type of reliability refers to demonstrated associations among multiple items representing a single construct?

VALIDITY

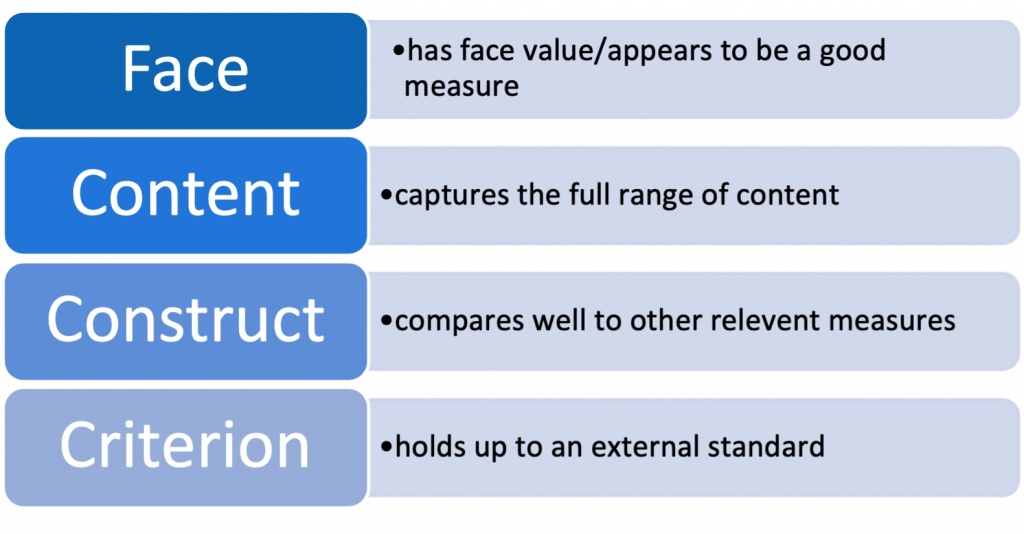

Perhaps even more important than ensuring consistency in measurement, we need to be certain that we are measuring the intended construct of interest. Validity is a term used by quantitative researchers to refer to the extent to which a study examines what it intends to. Not all reliable measures are valid. We might reliably weigh ourselves with a scale that consistency tells us the wrong weight because the dial was set two kilograms too high. Similarly, we may depend upon an alarm clock that is consistently ahead of schedule by a few minutes because it was incorrectly programmed. In this section, you will learn about four methods for evaluating the extent to which a given measure is measuring what it is intended to using face validity, content validity, construct validity, and criterion validity.

Face Validity

First, in trying to determine if a measure is a good indicator of an intended construct, we can assess the measure’s face validity. Face validity refers to the extent to which an instrument or variable appears on the surface or “face” to be a good measure of the intended construct. Grade point average, for example, appears to be a pretty good measure of a student’s scholastic ability, just as net yearly income seems like a valid measure of financial wealth. Your criteria for determining whether something has face validity is an assessment of whether the operationalization used is logical. For example, in the case of giftedness, most teachers would agree that children who exhibit very superior intellectual ability (i.e., the ability to reason at high levels) also tend to exhibit very superior academic ability (e.g., the ability to function at higher than normal levels in specific academic areas, such as math or reading).

Content Validity

Content validity refers to the extent to which a measure includes the full range or meaning of the intended construct. To adequately assess your knowledge of the general field of psychology, for example, a test should include a broad range of topics, such as how psychologists conduct research, the brain and mental states, sensation, perception, and learning. While a person might not score evenly across all areas of psychology (e.g., a student might score 20 out of 20 on the questions related to sensation and perception and only 15 out of 20 on items about research methods), the test result (35/40) should provide a general measure of knowledge regarding introductory psychology. Similarly, the Gifted Rating Scale discussed earlier is an instrument designed to identify giftedness that includes not only items related to intellectual ability but also content pertaining to the dimensions of academic ability, creativity, leadership, and motivation. This is not to say that a person scoring in the gifted range will achieve the same ratings on all items. For example, it is possible for a gifted child to score in the very superior range for intellectual and academic ability as well as creativity but score only superior for motivation and average for leadership. However, when taken together, the overall (i.e., full-scale) IQ score is 130 or greater for a gifted individual.

Construct Validity

Another way to assess validity is through construct validity, which examines how closely a measure is associated with other measures that are expected to be related, based on prior theory. For example, Gottfredson and Hirschi’s (1990) general theory of crime rests on the assumption that a failure to develop self-control is at the root of most impulsive and even criminal behaviours. Impulsivity, as measured by school records, such as report cards, should then correspond with other impulsive behaviours, such as deviant and/or criminal acts. If a study fails to show the expected association (e.g., perhaps children who fail to complete assignments or follow rules in school as noted on reports cards do not engage in higher levels of criminal or deviant acts relative to children who appear to have more self-control in the classroom), then the measures of missed assignments and an inability to follow rules may not be valid indicators of the construct. That is, the items stated on a report card, for example, incomplete assignments, may be measuring something other than impulsivity, such as academic aptitude, health issues, or attention-deficit problems. In this case, a better school indicator of impulsivity might be self-reported ratings of disruptive behaviour by the students themselves or teachers’ ratings of student impulsivity rather than the behavioural measures listed on a report card. Alternatively, behavioural measures from other areas of a person’s life, such as a history of unstable relationships or a lack of perseverance in employment, may be better arenas for assessing low self-control than the highly monitored and structured early school environment.

Criterion Validity

Finally, a measure of some construct of interest can be assessed against an external standard or benchmark to determine its worth using what is called criterion validity. We can readily anticipate that students who are excelling are also more likely to achieve academic awards, such as scholarships, honours, or distinction, and go on to higher levels. Academic ability as measured by grades or grade point averages is predictive of future school and scholastic success. Similarly, consider how most research-methods courses at a university or college have a prerequisite, such as a minimum grade of C– in a 200-level course. The prerequisite indicates basic achievement in the course. It is the cut-off for predicting future success in higher-level courses in the same discipline. The prerequisite has criterion validity if most students with the prerequisite end up successful navigating their way through research methods. All four types of validity are summarized in figure 4.5.

Test Yourself

- Are all reliable measures valid? Explain your answer.

- What does it mean to say a measure has face validity?

- What does content validity assess?

- Which type of validity is based on the prediction of future events?

Activity: Reliability and Validity

RANDOM AND SYSTEMATIC ERRORS

Researchers and research participants are potential sources of measurement error. Think about the last time you took a multiple-choice test and accidently entered a response of d when you intended to put e, or when you rushed to finish an exam and missed one of the items in your answer because you didn’t have time to re-read the instructions or your answers before handing in the test. Similarly, errors occur in research when participants forget things, accidently miss responses, and otherwise make mistakes completing research tasks. Also, researchers produce inconsistencies in any number of ways, including by giving varied instructions to participants, by missing something relevant during an observation, and by entering data incorrectly into a spreadsheet (where a 1 might become an 11). Errors that result in unpredictable mistakes due to carelessness are called random errors. Random errors made by participants can be reduced by simplifying the procedures (e.g., participants make fewer mistakes if instructions are clear and easy to follow and if the task is short and simple). Even researchers’ and observers’ unintentional mistakes can be reduced by using standardized procedures, simplifying the task as much as possible, training observers, and using recording devices or apparatus other than people to collect first-hand data (e.g., replaying an audio recording for verification following an interview). Random errors mostly influence reliability since they work against consistency in measurement.

In contrast to random errors, systematic errors refer to ongoing inaccuracies in measurement that come about through deliberate effort. For example, a researcher who expects or desires a finding might behave in a manner that encourages such a response in participants. Expecting a treatment group to perform better than a control group, a researcher might interpret responses more favourably in the treatment group and unjustifiably rate them higher. The use of standardized procedures, such as scripts and objective measures that are less open to interpretation, can help reduce researcher bias. In addition, it might be possible to divide participants into two groups without the researcher being aware of the groups until after the performance scores are recorded.

Study participants make other types of intentional errors, including ones resulting from a social desirability bias. Respondents sometimes provide untruthful answers to present themselves more favourably. Just as people sometimes underestimate the number of cigarettes they smoke when asked by a family physician at an annual physical examination, survey respondents exaggerate the extent to which they engage in socially desirable practices (e.g., exercising, healthy eating) and minimize their unhealthy practices (e.g., overuse of non-prescription pain medicine, binge drinking). Researchers using a questionnaire to measure a construct sometimes build in a lie scale along with the other dimensions of interest. For example, in the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire—Revised (EPQR), there are 12 lie-detection items, including the statements “If you say you will do something, do you always keep your promise no matter how inconvenient it might be?”; “Are all your habits good and desirable ones?”; and “Have you ever said anything bad or nasty about anyone?” A score of 5 or more indicates social desirability bias (Eysenck et al., 1985).

Similarly, participants in experimental research sometimes follow what Martin Orne (1962) called demand characteristics or environmental cues, meaning they pick up on hints about what a study is about and then try to help along the researchers and the study by behaving in ways that support the hypothesis. Systematic errors influence validity since they reduce the odds that a measure is gauging what it is truly intended to.

Test Yourself

- Who is a potential source of error in measurement?

- Which main form of errors can be reduced by simplifying the procedures in a study?

- What is the term for the bias that results when respondents try to answer in the manner that makes them look the most favourable?

RIGOUR IN QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

While it is important for anyone learning about research to understand the centrality of reliability and validity criteria for assessing measurement instruments, it is also imperative to note that much of what has been discussed in this chapter pertains mainly to quantitative research that is based in the positivist paradigm. Qualitative research, largely based in the interpretative and critical paradigms, is aimed at understanding socially constructed phenomena in the context in which it occurs at a specific point in time. It is therefore less concerned with the systematic reproducibility of data. In many cases, statements provided by research participants or processes studied cannot be replicated to assess reliability. Similarly, if we are to understand events from the point of view of those experiencing them, validity is really in the eyes of the individual actor for whom that understanding is real. That is not to say reliability and validity are not relevant in qualitative research; in fact, if we conclude that these constructs are not applicable to qualitative research, then we run the risk of suggesting that qualitative inquiry is without rigour. As defined by Gerard A. Tobin and Cecily M. Begley (2004), “rigour is the means by which we show integrity and competence; it is about ethics and politics, regardless of the paradigm” (p. 390). This helps to legitimize a qualitative research process.

Just as various forms of reliability and validity are used to gauge the merit of quantitative research, other criteria such as rigour, credibility, and dependability can be used to establish the trustworthiness of qualitative research. Credibility (comparable to validity) has to do with how well the research tells the story it is designed to. For example, in the case of interview data, this pertains to the goodness of fit between a respondent’s actual views of reality and a researcher’s representations of it (Tobin & Begley, 2004). Credibility can be enhanced through the thoroughness of a literature review and open coding of data. For example, in the case of a qualitative interview, the researcher should provide evidence of how conclusions were reached. Dependability is a qualitative replacement for reliability and this “is achieved through a process of auditing” (Tobin & Begley, 2004, p. 392). Qualitative researchers ensure their research processes, decisions, and interpretation can be examined and verified by other interested researchers through audit trails. Audit trails are carefully documented paper trails of an entire research process, including research decisions such as theoretical clarifications made along the way. Transparency, detailed rationale, and justifications all help to establish the later reliability and dependability of findings (Liamputtong, 2013).

Similarly, while questions of measurement and the operationalization of variables may not apply to qualitative research, questions concerning how the research process was undertaken are essential. For example, in a study using in-depth interviews, were the questions posed to the respondents in a culturally sensitive manner that was readily understood by them? Did the interview continue until all important issues were fully examined (i.e., saturation was reached)? Were the researchers appropriately reflective in considering their own subjectivity and how it may have influenced the questions asked, the impressions they formed of the respondents, and the conclusions they reached from the findings (Hennick et al., 2011)? Qualitative researchers acknowledge subjectivity and accept researcher bias as an unavoidable aspect of social research. Certain topics are examined specifically because they interest the researchers! To reconcile biases with empirical methods, qualitative researchers openly acknowledge their preconceptions and remain transparent and reflective about the ways in which their own views may influence research processes.

Achieving Rigour through Triangulation

One of the main ways rigour is achieved in qualitative research is by using triangulation. Triangulation is the use of multiple methods to establish what can be considered the qualitative equivalent of reliability and validity (Willis, 2007). For example, we can be more confident in data collected on aggressive behavioural displays in children if data obtained from field notes taken during observations closely corresponds with interview statements made by the children themselves. We can also be more confident in the findings when multiple sources converge (i.e., data triangulation), as might be the case if the children, teachers, and parents all say similar things about the behaviour of those being studied. Since the data comes from various sources with different perspectives, the data itself can also exist in a variety of forms, from comments made by parents and teachers, to actions undertaken by children, to school records and other documents, such as report cards.

Other Means for Establishing Rigour

Various alternative strategies to triangulation that help to establish rigour in qualitative studies include the use of member checks, prolonged time spent with research participants in a research setting, peer debriefing, and audit checking (Liamputtong, 2013; Willis, 2007). Member checks are attempts by a researcher to validate emerging findings by testing out their accuracy with the originators of that data while still in the field. For example, researchers might share observational findings with the group being studied to see if the participants concur with what is being said. It helps to validate the data if the participants agree that their perspective is being appropriately conveyed by the data. Whenever I conduct interviews with small groups (called focus groups, as discussed in chapter 9), I share the preliminary findings with the group and ask them whether the views I am expressing capture what they feel is important and relevant, given the research objectives. I also ask whether the statements I’ve provided are missing any information that they feel should be included to more fully explain their views or address their concerns about the topic.

Qualitative researchers also gain a more informed understanding of the individuals, processes, or cultures they are studying if they spend prolonged periods of time in the field. Consider how much more you know about your fellow classmates at the end of term compared to what you know about the group on the first day of classes. Similarly, over time, qualitative researchers learn more and more about the individuals and processes of interest once they gain entry to a group, establish relationships, build trust, and so on. Time also aids in triangulation as researchers are better able to verify information provided as converging sources of evidence are established.

In addition to spending long periods of time in the field and testing findings via their originating sources, qualitative researchers also substantiate their research by opening it up to the scrutiny of others in their field. Peer debriefing involves attempts to authenticate the research process and findings through an external review provided by another qualitative researcher who is not directly involved in the study (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). This process helps to verify the procedures undertaken and substantiate the findings, lending overall credibility to the study. Note that reflexivity and other features underlying ethnographic research are discussed in detail in chapter 10, while multiple methods and mixed-methods approaches are the subject matter of chapter 11.

Test Yourself

- What is the qualitative term for validity?

- How do qualitative researchers ensure their research processes and conclusions reached can be verified by other researchers?

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- Describe the main components of a research design.

A research design details the main components of a study, including who (the unit of analysis), what (the attitudes or behaviours under investigation), where (the location), when (at one or multiple points in time), why (e.g., to explain), and how (the specific research method used). - Explain what conceptualization and operationalization processes entail.

Conceptualization is the process whereby a researcher explains what a concept, such as family, or a construct, like social inequality, means within a research project. Operationalization is the process whereby a concept or construct is defined so precisely it can be measured in a study. For example, financial wealth can be operationalized as net yearly income in dollars. - Explain how the purpose of a variable is directly related to how it is measured in research.

Variables are measured at the nominal, ordinal, interval, and ratio level. The nominal level of measurement is used to classify case, while the ordinal level has the property of classification and rank order. The interval level provides the ability to classify, order, and make precise comparisons as a function of equal intervals. The ratio level includes previous properties and a true zero. An index is a composite measure of a construct comprising several different indicators that produce a shared outcome, while a scale is a composite measure of a construct consisting of several different indicators that stem from a common cause. - Outline the main techniques used to assess reliability and validity.

Reliability refers to consistency in measurement. Test-retest reliability examines consistency between the same measures for a variable at two different times using a correlation coefficient. Inter-rater reliability examines consistency between the same measures for a variable of interest provided by two different raters, often using Cohen’s kappa. Split-half reliability examines consistency between both halves of the measures for a variable of interest. Inter-item reliability involves demonstrated associations among multiple items representing a single construct. Validity refers to the extent to which a measure is a good indicator of the intended construct. Face validity refers to the extent to which an instrument appears to be a good measure of the intended construct. Content validity assesses the extent to which an instrument contains the full range of content pertaining to the intended construct. Construct validity assesses the extent to which an instrument is associated with other logically related measures of the intended construct. Criterion validity assesses the extent to which an instrument holds up to an external standard, such as the ability to predict future events. - Distinguish between random and systematic errors.

Random errors are unintentional and usually result from careless mistakes, while systematic errors result from intentional bias. Sources of both types of errors include participants, researchers, and observers in a study. Errors can be reduced through training, the use of standardized procedures, and the simplification of tasks. - Explain how rigour is achieved in qualitative research.

Rigour refers to a means for demonstrating integrity and competence in qualitative research. Rigour can be achieved using triangulation, member checks, extended experience in an environment, peer review, and audit trails.

RESEARCH REFLECTION

- Suppose you want to conduct a quantitative study on the success of students at the post-secondary institution you are currently attending. List five variables that you think would be relevant for inclusion in the study. Generate one hypothesis you could test using two of the variables you’ve listed above. Operationalize the variables you included in your proposed hypothesis.

- Studies on the health of individuals often operationalize health as self-reported health using these five fixed response categories: poor, fair, good, very good, and excellent. What level of measurement is this? Provide an example of health operationalized into two categories measured at the nominal level and three categories at the ordinal level. Is it possible to measure health at the interval level? Justify your answer.

- Consider some of the variables that can be used to examine the construct of scholastic ability (e.g., grades, awards, and overall grade point average). Which measure do you think best represents scholastic ability? Is the measure reliable and/or valid? Defend your answer with examples that reflect student experiences.

- Define the construct of honesty and come up with an indicator that could be used to gauge honesty. Compare your definition and indicator with those of at least three other students in the class. Are the definitions similar? Consider how each definition reflects a prior conceptualization process.

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE

Objective: To construct an index for students at risk for degree incompletion

Directions:

- Item selection: Develop 10 statements that can be answered with a forced-choice response of yes or no, where yes responses will receive 1 point and no responses will be awarded 0 points. Select items that would serve as good indicators of students at risk for failing to complete their program of study. Think of behaviours or events that would put a student at risk for dropping out or being asked to leave a program, such as failing a required course. Make sure your items are one-dimensional (i.e., they only measure one behaviour or attitude).

- Try out your index on a few of your classmates to see what scores you obtain for them. Is there any variability in the responses? Do some students score higher or lower than others?

- Come up with a range of scores you feel represent no risk, low risk, moderate risk, and high risk. Justify your numerical scoring.

RESEARCH RESOURCES

- For more information on the four types of validity discussed in this chapter, see Middleton, F. (2023, June 22). The 4 types of validity in research. Definitions and examples. Scribbr.

- To learn more about rigour in research, refer to “The Feast Centre Learning Series: ‘Rigour’ in Research Proposals” at McMaster University.

- For an in-depth look at scale development, see DeVellis, R. F. and Thorpe, C. T. (2022). Scale development: Theory and applications (5th ed.). Sage.

- To learn about a new online gambling index based on 12 items, see Auer, M. et al. (2024). Development of the Online Problem Gaming Behavior Index. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 47(1), 81-92.

- Cohen’s kappa is generally used only with nominal variables. If the variables of interest are at the ordinal or interval/ratio level, Krippendorff’s alpha is recommended (Lombard et al., 2002). ↵

The plan or blueprint for a study, outlining the who, what, where, when, why, and how of an investigation.

The object of investigation.

Research conducted at a single point in time.

Research conducted at multiple points in time.

Research on the same unit of analysis carried out at multiple points in time.

Research on the same category of people carried out at multiple points in time.

Research on different units of analysis carried out at multiple points in time.

Research on a small number of individuals or an organization carried out over an extended period.

Abstract mental representations of important elements in our social world.

The process where a researcher explains what a concept means in terms of a research project.

Intangible idea that does not exist independent of our thinking.

A measurable quantity that in some sense stands for or substitutes for something less readily measurable.

The process whereby a concept or construct is defined so precisely that it can be measured.

A level of measurement used to classify cases.

A level of measurement used to order cases along some dimension of interest.

A level of measurement in which the distance between categories of the variable of interest is meaningful.

An interval level of measurement with an absolute zero.

A composite measure of a construct comprising several different indicators that produce a shared outcome.

A composite measure of a construct consisting of several different indicators that stem from a common cause.

Consistency in measurement.

Consistency between the same measures for a variable of interest taken at two different points in time.

Consistency between both halves of the measure for a variable of interest.

Consistency between the same measures for a variable of interest provided by two independent raters.

Demonstrated associations among multiple items representing a single concept.

The extent to which a study examines what it intends to.

Assesses the extent to which an instrument appears to be a good measure of the intended construct.

Assesses the extent to which an instrument contains the full range of content pertaining to the intended construct.

Assesses the extent to which an instrument is associated with other logically related measures of the intended construct.

Assesses the extent to which an instrument holds up to an external standard, such as the ability to predict future events.

Measurement miscalculation due to unpredictable mistakes.

Miscalculation due to consistently inaccurate measures or intentional bias.

A means for demonstrating integrity and competence in qualitative research.

An assessment of the goodness of fit between the respondent’s view of reality and a researcher’s representation of it.

An assessment of the researcher’s process as well documented and verifiable.

Attempts made by a researcher to carefully document the research process in its entirety.

The use of multiple methods or sources to help establish rigour.

The reliance on multiple data sources in a single study.

Attempts made by a researcher to validate findings by testing them with the original sources of the data.

Attempts made by a researcher to authenticate the research process and findings through an external review provided by an independent researcher.