Chapter 9: Qualitative Interviewing

Rather than stripping away context, reducing people’s experiences to numbers, in-depth interviewing approaches a problem in its natural setting, explores related and contradictory themes and concepts, and points out the missing and the subtle as well as the explicit and the obvious.

— Herbert J. Rubin & Irene S. Rubin, 2012, p. xv

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, students should be able to do the following:

- Explain what a qualitative interview is.

- Describe the structure of qualitative interviews and explain why qualitative interviewing is “responsive.”

- Identify and explain important considerations that arise in the main steps for conducting a qualitative interview.

- Define and differentiate between main question types.

- Define focus group and compare focus groups to in-depth interviews.

- Describe the main components of a focus group.

INTRODUCTION

In chapters 6 and 7, you learned about two quantitative approaches based on deductive logic, stemming from the positivist paradigm and resting on objective conceptions of social reality (i.e., surveys and experiments). In this chapter, you will learn about a qualitative method known as qualitative interviewing, which is grounded in the interpretive paradigm in its emphasis on naturalism and subjective understanding. A qualitative interview, also known as an intensive interview, an in-depth interview, or just a depth interview, is an approach to research that “attempts to understand the world from the subjects’ points of view, to unfold the meaning of their experiences, [and] to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009, p. 1). You are already familiar with the many uses of interviews in the social world as evident in places of employment, where they are regularly relied upon for hiring and promotional purposes. Interviews are an integral part of therapeutic and correctional processes used to assess, monitor, and rehabilitate clients and offenders. Interviews are also employed in everyday life by reporters, historians, and authors who wish to learn more about a person of interest’s life, career, or accomplishments. Similarly, qualitative interviewing is an especially popular method among researchers interested in understanding processes, organizations, and events from the perspective of those most knowledgeable about such phenomena—the people who directly experience the processes, who work within the organizations, and/or who undergo or are most impacted by the conditions of interest.

Poulin et al. (2018), for example, conducted in-depth interviews with self-identified gay and lesbian soldiers in the Canadian military to understand how their experiences are impacted by an environment supportive of hyper-masculinity (exaggerated stereotypical male behaviour) and heteronormativity (adherence to binary gender codes). Participants revealed discrimination tied to the policing of masculinity and femininity, as well as the use of various coping strategies, including having to prove they met a “warrior” standard or passing for a heterosexual (Poulin et al., 2018). As another example, Walsh et al. (2016) interviewed immigrant women who were newcomers to Montreal, Quebec to learn about housing insecurity. The researchers found insecure housing was linked to various factors, including an ineligibility for government programs due to immigration status, a lack of experience in Canada, and a traumatic migration trajectory such as war or persecution in the country of origin (Walsh et al., 2016).

QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW STRUCTURE

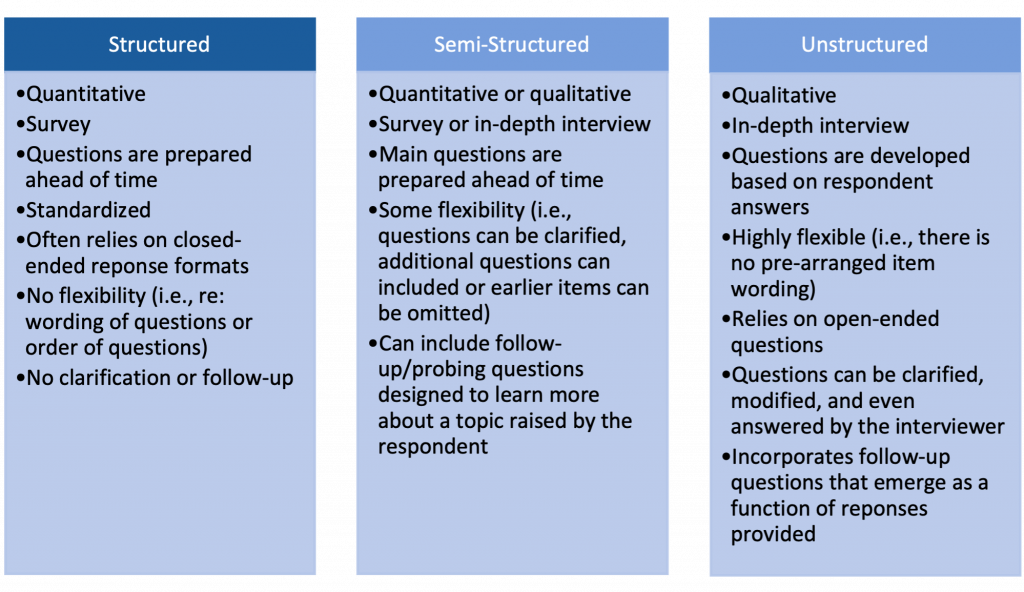

While quantitative interviewing in the form of a survey tends to be a formal, direct, and highly structured data collection method, qualitative in-depth interviewing is based on informal and flexible approaches to data collection. Qualitative interviews can be semi-structured in format, where some of the questions or an outline of potential questions is prepared ahead of time, with room to clarify responses and probe for additional details. The format of qualitative interviews can also be completely unstructured, where question wording develops in the moment like a casual conversation consisting of a variety of friendly exchanges between the interviewer and interviewee, with flexibility in choice of topics and issues explored. (See figure 9.1 for a comparison of structured, semi-structured, and unstructured approaches to interviewing.) Since qualitative interviewing relies on listening, understanding, and asking questions, it shares features with everyday conversations, including a fundamental social component. Like two friends having a private conversation, the qualitative interviewer needs to establish trust and rapport, and even needs to be able to “read” unspoken cues evident in non-verbal forms of communication, such as facial expressions or tone of voice. However, a qualitative interview is not a casual conversation because, unlike casual conversations, qualitative interviews have an established purpose, they tend to involve more questioning from the interviewer and more responding from the interviewee, and they deliver much more detail (Rubin & Rubin, 2012).

In addition, while a quantitative survey consists of mainly closed-ended items (see chapter 7), a qualitative interview comprises open-ended questions, where participants are asked to describe their views and personal experiences, however they make sense of those experiences, in their own words. The order of the questions and even the content of any given question can vary from participant to participant, although covering the same topics and even the same questions may be desirable for later comparing the responses across different interviewees. The central underlying feature of qualitative interviewing that makes it unique is its reliance on what Rubin and Rubin (2012) refer to as a “responsive” approach. Responsive interviewing “emphasizes flexibility of design and expects the interviewer to change questions in response to what they are learning” (p. 7). The qualitative interviewer’s main objective is to listen carefully to what the interviewee is saying to achieve a basic understanding and then, dependent upon what the interviewer hears, subsequently probe the interviewee for verification and for additional details to achieve an even deeper and more thorough understanding. The flexibility of the design is what makes responsiveness possible, rendering in-depth interviews one of the only methods that can be used to truly “get inside a person’s head” (Tuckman, 1972) so we can understand “the lived experience” of that person (Seidman, 2006).

Many exploratory topics that begin with the question “What’s it like to …?” are especially suited to qualitative interviewing. Listed here are some examples that follow from “What’s it like to …”:

- Undergo a transition from a two-year college to a four-year degree-granting university?

- Grieve the loss of a loved one due to an unexpected accident?

- Be a member of an outlaw motorcycle gang?

- Be a professional poker player?

- Live out a life sentence for murder while on parole?

- Stay at a shelter after leaving an abusive relationship?

Research on the Net

Forum: Qualitative Social Research

Forum: Qualitative Social Research (FQS) is a peer-reviewed open-access journal for qualitative research that was started in 1999. This multilingual online journal publishes articles based on studies conducted using qualitative methods. Visit their website to learn more about the use of biographies, in-depth interviews, participatory qualitative research, qualitative archives, visual methods, and much more!

Test Yourself

- In what ways does a qualitative interview differ from a quantitative survey?

- In what ways does a qualitative interview differ from a casual conversation?

- In what ways is qualitative interviewing considered to be a reflexive process?

CONDUCTING A QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW

After settling on a topic, narrowing the focus, and developing a research question, as is the case in any research project, main stages for conducting a qualitative interview include determining the type of format to use, selecting a sample, working through ethical considerations, establishing rapport, developing questions ahead of time and/or while carrying out the interview, coding and analyzing the interview data, and disseminating the findings. Special considerations are associated with some of these stages, as discussed in the following sections.

Determining the Most Appropriate Structure

Deciding upon the structure for a qualitative interview depends in part on the nature of the research question and the overall purpose of the study, on the anticipated sample, and on various other considerations, such as the amount of time and resources available for the project. First, it is important to consider what the interview is designed to accomplish. For example, if the purpose is to assess the needs and requirements of individuals so they can perhaps receive the most appropriate therapy or treatment, then a semi-structured interview is likely since specific kinds of information will be sought. Similarly, if the interview is designed to test an assumption or more fully explain a process, it is likely to be semi-structured since the objectives are known in advance. In contrast, an interview designed to identify processes or relationships that will become the focus of a later study, or an interview follow-up from another method such as an experiment, used to learn more about why things happened the way they did, would likely be unstructured. Unstructured interviews also work best for research designed to get at people’s lived experiences. Ethnographic research that takes place in natural settings heavily relies upon unstructured, in-depth interview techniques (see chapter 10). In many cases, the decision about structure boils down to how much control the researcher needs to have over the type of responses provided by the interviewees (Bernard, 2018).

Sample considerations also impact the structure of an interview. For instance, if the intended sample comprises a group whose responses will be compared for similarities and differences, interviews will be more structured than would be the case if there was only going to be one person interviewed because that person is perhaps considered to be the starting point, serves as an usual case, or is an extreme example of some topic of interest. Here, the issue is more one of whether the researcher wishes to obtain comparable responses, suggesting more structure to the design, versus a unique understanding, which warrants a less structured approach (Cohen et al., 2018).

Overall, unstructured interviews are an excellent means for obtaining rich, detailed information on a topic of interest from the point of view of the participant. Credibility is likely to be high because the unstructured approach of an in-depth interview is flexible enough to allow for clarification of questions and the use of prompts based directly on the responses provided by an interviewee. This helps ensure that the data obtained are a close approximation of the respondent’s construction of reality. However, the researcher still needs to reconstruct or interpret the transcribed data in a manner that is consistent with the respondent’s perspective in order to disseminate the findings. While reliability in the “quantitative” sense is likely to be low, especially if the questions were tailored to a participant and may not lend well to replication with different participants, dependability can be high if the researcher is careful to document the research process, including interpretations of the findings and justification for the conclusions reached. See chapter 4 for more information on how rigour is achieved in qualitative research.

Selecting a Sample

Qualitative research is usually more concerned with gaining an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon from those experiencing it than it is with obtaining results that generalize from a large representative sample to a population of interest. As a result, qualitative researchers carefully select for interviewees using techniques such as purposive sampling or snowball sampling to identify and locate the most appropriate participants (see chapter 5 for a discussion of the various sampling techniques). Ideal interviewees are well informed about the research topic (i.e., they have first-hand experience with the event, process, condition, or issue being studied). As Rubin and Rubin (2005) note, finding knowledgeable participants is often not as easy as it first appears to be since “not everyone who should know about something is necessarily well informed,” p. 65). In addition, researchers try to select for interviewees who can offer a diverse range of perspectives and opinions on the same topic. For example, to fully appreciate the collective experience of a two-year community college transitioning to a four-year undergraduate degree granting university, researchers might interview a small number of students, instructors, advisors, support staff, and administrators who were present at the educational institution prior to, during, and after the change in status.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical concerns need to be taken into consideration during the early planning stage of a study. Most social research projects entail at least a minimal risk of harm to participants, and in-depth interviews are no exception. The difficulty with in-depth interviews for both researchers and research ethics review board members lies in anticipating in advance the kinds of risks likely to be experienced by participants, since the questions that evoke emotion or otherwise affect interviewees develop within the research process itself. There are several ways to mitigate for potential risks. First, researchers should be qualified to carry out in-depth interviews. To obtain ethical approval for a study based on qualitative interviews, for example, researchers generally need to validate their qualifications by indicating their prior research experience, by demonstrating their familiarity with use of qualitative interview techniques, and by providing evidence of completion of the Tri-Council Policy Statement CORE-2022 course on research ethics (see chapter 3 for a detailed discussion of the TCPS 2; Canadian Institutes of Health Research [CIHR] et al., 2022) on research involving humans as participants). In addition, researchers may be required to provide a detailed project description, a literature review that establishes the scholarly context for the study, and a summary of the methodology including details about the recruitment of participants.

Anticipated risks and benefits to participants are also described in advance to an ethics review board (see chapter 3). Researchers detail potential sources of psychological harm that could result from the type of questions the researcher plans to ask. This is usually accomplished through the creation of an interview guide. An interview guide is like an outline that consists a series of key questions developed by the researcher after consulting the relevant academic and non-academic literature and considers any “hunches” about what might be relevant or beyond what is already known (Rapley, 2007). An interview guide helps to frame the interview based on the overall objectives of the study. Although this will only be loosely followed during the actual interview, an interview guide or set of main questions helps to inform the ethics board and potential interviewees about what participation is expected to entail, as part of the informed consent process. Researchers also need to identify specific means for mitigating potential risks posed by the study. For example, a researcher planning on interviewing students about their aggressive driving practices can note that questions about unsafe driving practices will be asked during the interview and can even provide a few sample potential questions. In addition, potential participants can be made aware that they may find some of the questions to be embarrassing or uncomfortable to answer. Finally, a researcher can debrief participants with information that helps them to address their emotions and/or actions beyond the study, such as a listing of local driver education resources and/or anger management resources.

Maintaining privacy is another ethical consideration that necessitates special consideration when planning a study based on qualitative interviewing. Anonymity, as in not knowing who the participant is (see chapter 3), cannot be achieved since an interviewer knows who is being interviewed. Moreover, since the sample size is small for in-depth interview methods, the findings do not get reported as group data in a manner that would obscure the identity of participants as is the case with quantitative survey methods. Instead, the researcher is likely to note themes and use quotes from participants to substantiate the findings. How, then, does a qualitative researcher protect the identity of interviewees? There are several ways to protect the identity of interview subjects. First, a pseudonym or alias name can be attached to the interviewee’s comments. In addition, identifying details can be removed or left out of the published findings. For example, in explaining how sociology student Kaitlin Fischer (original name) described her experience within one of the first graduating classes from the Bachelor of Arts program at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, the researchers might simply state “a female student taking sociology notes.…” But what would happen if the researchers wanted to share information provided by the president of the university or one of the deans? When there are only a few individuals in a given role or the field of study is quite small, it is highly likely that even when names are left off, information made public could inadvertently identify the participant (e.g., there is only one president). Researchers could in this case conceal the role of the participant by generalizing the position to “an administrator” or by broadening the description of the institution, as in “a president at a university in Eastern Canada.”

Researchers even need to ensure that others outside of the study cannot compromise privacy by gaining access to the data. Since most interviews are recorded, and that information is often stored on the computer of the principal researcher, privacy could be compromised if the researcher’s computer were stolen or accessed by someone else. Ethics review boards ask for information on how the data will be collected and stored and who will have access to the data. Password-protected software helps to alleviate concerns about unauthorized access but still might not resolve the issue of data being subpoenaed by the criminal justice system in cases involving interviews that expose criminal activity. Since this cannot always be anticipated ahead of time, researchers need to carefully think through how they will handle sensitive information they may become privy to. As noted in chapter 3, qualitative researchers have been successful in winning court cases based on the need to protect participant confidentiality (e.g., see Samson, 2014).

Establishing Rapport

In all forms of qualitative research, the researcher is the data-gathering instrument. In the case of an in-depth interview, this means the quality and amount of data collected largely rests with the interviewer’s ability to establish and maintain rapport with the interviewee. Due to the personalized nature of any given in-depth interview, there are no guaranteed methods for establishing great rapport. An interviewer, however, should try to do whatever is possible, given the circumstances, to make an interviewee feel at ease and valued for whatever contributions may be forthcoming. After all, it is the views of the interviewee that are essential to the study itself. Making the interviewee feel comfortable is not an easy task, as everything about the interviewer, including how an interviewer looks, acts, and conducts the interview, may have an impact on the interviewee, even if indirectly, and influence the success of the interview itself. Just as some instructors are better than others at engaging with their students, some interviewers are more adept at developing rapport. Think about what is likely to happen when a student offers up an incomplete or incorrect answer in class and the instructor’s sharp rebuttal makes that student feel embarrassed or ashamed. The student will be less likely to speak up in the future. If, instead, the instructor had thanked the student for responding, clarified the answer, and reassured the student, the same student might be just as willing to try again at another point in time. Similarly, an interviewer needs to create a safe climate where a participant is encouraged to offer up information with an implicit understanding that responses are appreciated and the participant is not being judged by the interviewer.

In the development of this climate, it is even important to consider the physical location in which the interview takes place. The location and setting for an interview should be one that is familiar to the participant and makes the person feel at ease discussing personal issues. Many in-depth interviews take place in the home or workplace of the interviewee, or in a public location, such as a restaurant or coffee shop, that offers privacy and is convenient for the participant. The important consideration in choosing a location for an interview is to make sure it is a place where the interviewee will feel comfortable and can speak freely about the topics raised in the interview.

Lune and Berg (2021) identify three crucial techniques employed by interviewers to help build trust and establish rapport during interviews including tolerating “uncomfortable silence,” “echoing” the interviewee, and “letting people talk” (p. 78). Tolerating uncomfortable silence means an interviewer should purposely build in long, silent pauses after asking an interviewee a question. Interviewees require time to consider the question, think about how it relates to them and the situation as they understand it, and then try to formulate an answer. As a teaching analogy, I have conducted peer reviews on probationary instructors to provide them with feedback on their teaching. During peer reviews, inexperienced instructors often fail to give students enough time to digest a question posed before the nervous instructor answers it for them. Lune and Berg (2021) recommend waiting for up to 45 seconds before assuming an interviewee truly has nothing to say about a subject.

Echoing the interviewee involves acknowledging what the interviewee is saying by repeating back the main idea. This technique conveys interest and understanding. It also helps establish and maintain rapport because the interviewee is inadvertently encouraging the interviewer to continue (Lune & Berg, 2021). The key to this technique is to keep it brief and only echo back what the interviewee has said, as demonstrated in the following exchange:

Interviewer: “Can you tell me what it was like when you learned your son was highly gifted?”

Interviewee: “When I initially read the results of the intelligence test, I was relieved. The findings gave us an explanation for Brant’s disruptive behaviour at school.”

Interviewer: “So you were relieved because you had a reason for the disruptive behaviour?”

Interviewee: “Yes. Brant’s kindergarten teacher told us that Brant appeared to be low-functioning and easily distracted. Instead, he may have been highly capable but bored by the repetition.”

Imagine, instead, how the conversation might have gone if the interviewer was inexperienced and failed to use echoing correctly, inserting a personal viewpoint such as “I know what you mean, I was also a disruptive kid in school.” The point of the interview is to obtain needed information from the interviewee, whose perspective needs to remain front and centre throughout the interview process. The underlying goal is to let the participant lead most of the discussion.

Just as the researcher needs to do things to get the participant to feel at ease in order to facilitate the discussion, it is also important to do everything possible to maintain a conversation. Letting people talk literally means the interviewer must be careful not to interject at the wrong times. The worst mistake an interviewer can make in this regard is to interrupt an interviewee’s thought processing or react in a manner that interferes with an interviewee’s response, thereby losing potentially important data (Lune & Berg, 2021). It takes time to develop interviewer skills, and one of the best ways to learn how to conduct great interviews is through first-hand experience and practice. Just as we are apt to make mistakes in some of our exchanges with certain friends and family members, over time we also become more adept at reading cues and figuring out what is working and not working for interviewees.

Accomplished interviewers demonstrate active listening. Active listening is a technique in which the interviewer demonstrates an understanding of what is being said and expressed by the interviewee through feedback. Active listening is evident when an interviewer appropriately echoes the interviewee and uses emotional displays based on what the interviewee has expressed. For example, if a participant conveys a happy experience, the interviewer should appear happy by smiling and conversely, if the interviewee appears to be upset, the interviewer should acknowledge this, be empathetic, and possibly even try to console the person (Lune & Berg, 2021). A skilled interviewer is also able to steer an interviewee away from the tendency to answer with “monosyllabic” responses of “yes” or “no” using questioning techniques such as probes and pauses (Lune & Berg, 2021). Probes are defined and discussed in detail in the next section.

Types of Questions and Interview Sequencing

Various types of questions are routinely used in qualitative interviews. This section describes question types and outlines the order for the sequence of events in a typical interview.

Ice Breaker

An interview usually begins with an icebreaker, or opening question, that is unrelated to the research topic and is used specifically to establish rapport. The icebreaker can pertain to anything the interviewer feels will be effective for getting the participant talking. For example, the interviewer might begin by asking the participant something about the weather, or, if the interview takes place in the home of the participant, the interviewer might start by asking how long the participant has lived in the home, or by inquiring about a picture that is prominently displayed in the home. The icebreaker should always be a question that is easy for the interviewee to answer.

Informed Consent for Participation

Following the icebreaker, the interviewer can introduce the study by reiterating the overall purpose (e.g., objectives) and procedures. In many cases, the study will consist of a tape-recorded interview that is carried out in the home or workplace of the interviewee. Permission needs to be sought from the participant before starting the recording device. Additional details are also provided ahead of time, such as how long the interview will take and what the questions will pertain to. Also, as part of the consent process, the participant will need to be made aware of the benefits of the research (e.g., how the study will contribute to a better understanding of a particular condition experienced by the participant) and the potential risks (e.g., that the participant might find some of the questions to be embarrassing). Interviewees need to be made aware that participation is voluntary, and even with prior agreement, the participant can refrain from answering questions and can withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. If an interviewee chooses to end the study early, the participant is free to decide whether views provided up to that point are to remain as part of the data or will need to be removed from the study. A participant also needs to be informed ahead of time about how privacy will be protected. For example, how will potentially identifying information be stored and who will have access to it? In addition, the participant needs to be informed about how long data will be kept and how records will be destroyed once the study is completed. Finally, the participant needs to know how the findings will be reported (e.g., direct quotes may be used) and what the plans are for dissemination (e.g., findings may be reported at a conference and published in a peer-reviewed journal). These details should be contained in the consent form, which is reviewed with the participant prior to the onset of the interview. Assuming the participant approves of the conditions, signs the consent form, and agrees to be interviewed, the study can officially commence.

Transition Statements

Having established informed consent, the researcher can lead the participants into the focus of the study using a transition statement. Transition statements are designed to “move the conversation into the key questions that drive the study” (Krueger & Casey, 2015, p. 45). For example, in a study on teaching, I concluded the consent process with “If you have no further questions or concerns about what the study entails, I’m now going to collect the consent form from you and begin the interview.” To transition to the first question, I said, “Take a moment to think about the kinds of things you do to prepare for your classes.” After waiting about 45 seconds, I then asked, “What is one of the things you do to prepare for class?”

Essential Questions

Essential questions, also called key or main questions, “exclusively concern the central focus of the study” (Lune & Berg, 2021, p. 63). Essential questions are usually developed in advance of the interview and they form the basis of the interview guide. If demographic information is pertinent to the study, these items will generally be near the beginning of the interview (e.g., questions on age, marital status, and occupational status). Questions that more directly relate to the study topic follow from here, beginning with the least sensitive questions and then moving into the more sensitive ones once rapport is flowing well. Sensitive questions are ones that are most likely to pose the greatest risk of psychological harm by evoking emotions (e.g., asking about the loss of a loved one, asking the participant to retell a painful event, or asking about a private condition the interviewee is deeply affected by).

Probes

Probes are short questions and prompts designed to obtain additional information and details from a participant that will help to further understanding. Interviewees can be encouraged to elaborate on their responses through short prompts, such as “And then what happened?”; “Anything else?”; “How come?”; “Hmm”; “I see”; “Could you tell me more about X?”; “What do you mean by X?”; or “How did that make you feel?” As cultural anthropologist H. Russell Bernard (2018) puts it, “the key to successful interviewing is learning how to probe effectively—that is, to stimulate a respondent to produce more information, without injecting yourself so much into the interaction that you only get a reflection of yourself in the data” (p. 169). For example, suppose an interviewee is asked “Have you ever used illegal drugs while at work?” Assume the participant replies “Yes.” The next question can be the probe “Like what?” Note how this prompt enables the interviewee to choose the direction of the ensuing discussion (as opposed to the interviewer stating the name of some drug and waiting for the respondent to answer in the affirmative or negative, thereby leading the creation of the data obtained).

Throw-Away Questions

In cases where it may be difficult for an interviewee to stay focused on a central topic for long periods of time (e.g., because it is stressful or painful to relive), an interviewer can help the interviewee take breaks by asking occasional throw-away questions. Throw-away questions are unessential questions that may be unrelated to the research. Lune and Berg (2021) highlight the importance of using throw-away questions while probing sensitive issues to “cool out” the participant.

Extra Questions and Follow-Up Questions

One way to examine the reliability and validity of the responses being provided by the interviewee is to include extra questions and follow-up questions. Extra questions “are those questions roughly equivalent to certain essential ones but worded slightly differently” (Lune & Berg, 2021, p. 63). Extra questions help to assess reliability in responding since the interviewee should discuss similar issues in a consistent manner. Follow-up questions are “specific to the comments that conversational partners have made” (Rubin & Rubin, 2005, p. 136). Follow-up questions help to clarify main ideas or themes that emerge during the interview to ensure that the interviewer has properly understood the intended meaning of the main idea (e.g., Can you tell me more about …?). Follow-up questions are similar in nature to probes, but they are usually asked to obtain clarification about an issue central to the overall research objectives. Follow-up questions help to establish validity, since the aim of qualitative interviewing is to understand an issue from the viewpoint of the participant (Miller & Glassner, 2011). Follow-up questions may be asked within an initial interview or they may be asked in subsequent interviews after a researcher has had an opportunity to explore the findings to identify themes or concepts that warrant further clarification.

Closing Questions

While there is no set length to a qualitative interview and the actual length will largely be determined by the objectives of the study, the interviewee, and the overall dynamics that develop within the interview process, you can plan, as a general rule of thumb, for an interview to be about 90 minutes in length. Since friendly rapport is established within a new social relationship, it is sometimes difficult for the interviewer to bring the interview to an end. Closing questions are designed to help bring closure to the interaction by re-establishing distance between the interviewer and interviewer. (Hennink et al., 2011). Closing questions often consist of slightly reworked earlier statements about data storage and plans for the dissemination of the findings, since these topics reflect late stages of the study and are more technical than personal in nature. The final question in an interview asks if the participant has any questions about the research or anything else to add before the interview concludes. At that point, the participant is thanked for their time and contributions, and the participant is reminded to contact the researcher should any questions about participation arise later. A follow-up interview is sometimes scheduled at the end of the interview. In-depth interviews are generally not a one-time event. In most cases, the participants are interviewed on at least one other occasion. This is because the researcher needs time to analyze the information collected during the first interview (or round of interviews, if multiple people are interviewed for the same project) to determine which of the findings warrant further exploration.

Coding and Analyzing Interview Data

Assuming the interview was properly recorded in some manner, the information obtained during the interview can now be transcribed so that data analysis can take place. Transcription is a data-entry process in which the obtained verbal information is transferred verbatim (i.e., word for word), including, where possible, indications of mood, emotion, and pauses into a written (i.e., typed) format. Transcribing interview tapes or sound recordings into text is time consuming, and the longer the time elapsed between the interview and the transcription, the less able a researcher is to capture gestures or indications of special emphasis that took place during an interview (e.g., perhaps the interviewee shrugged their shoulders or fidgeted nervously prior to answering certain questions). As an example, it took students in one of my advanced qualitative methods courses six to eight hours, on average, to transcribe one 90-minute interview for a course assignment. Those who did the transcription right away were able to add in additional insights, such as lengthy pauses and facial expressions used by the interviewee. A few opted to save time using voice-activated software, which transcribed the interview for them with minimal errors. However, the students who transcribed the data themselves benefited from listening repeatedly to what the interviewee was saying, thereby increasing the detail and authenticity of their interpretations of the responses. Reliability can be assessed at the transcription phase using two transcribers, whose verbatim accounts of the interview should end up very similar, provided the audio recording is of adequate quality. Once the data is transcribed, it can be coded for themes, ideas, and main concepts.

Coding was defined in chapter 8 as means of standardizing data. Coding qualitative data involves “delineating concepts to stand for interpreted meaning of data” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 220). Recall that the purpose of a qualitative interview is to gain an understanding of a topic from the perspective of someone who has experienced it first-hand. Thus, if you were studying what it is like for someone to parent a highly distracted 10-year-old boy, your research findings should help others understand what distractibility means as explained by one of his parents. As you read through the transcription, you need to underline passages that identify main ideas. For example, the parent might note that the child “rarely remembers to bring home his homework,” that “teachers continually indicate that the boy cannot complete schoolwork independently,” and “that it takes hours upon hours to complete a short piece of homework.” These types of comments help to identify what distractibility means in terms of school-related behavioural indicators. The transcript might also contain other indicators of distractibility, such as social implications. For example, the interview transcript might include a comment that “he never gets invited to birthday parties even by the children who attend his party” and “no one ever comes to the door to call on him when the neighbourhood kids are going to the park.” The researcher’s task is to try to tell the story of distractibility from the perspective of the parent, highlighting main concepts and themes as reflected in the conversation.

In addition to the identification of key concepts, qualitative researchers pay attention to context. Context “is complicated notion. It locates and explains action–interaction within a background of conditions and anticipated consequences. In doing so, it links concepts and enhances a theory’s ability to explain” (Corbin & Strauss, 2015, p. 153). In relation to the distracted child, you might be tempted to conclude that the boy probably has something like an attention deficit disorder. However, the researcher would try to make sense of the distractibility in relation to other issues that help to provide a context for understanding why it occurs. For example, the researcher might note that most of the problems are only evident at school and in relation to age-related peers. Careful consideration of the transcript might also reveal that the child has a few close friends who are several years older. In addition, there may be passages indicating that the child has an unusually advanced sense of humour, learns new things very quickly, and is able to retain large amounts of information. These behaviourial traits are associated with giftedness. As noted in an earlier chapter, gifted children are those whose intelligence (as measured by standard IQ tests) is well out of the range of normal (i.e., over 130). Gifted children have a very low tolerance for repetitive tasks; they tend to have what is called sensual and intellectual overexcitability, where they easily become distracted in environments that are not interesting or highly challenging for them (Webb et al., 2005). Trying to make sense of distractibility in the context of giftedness clearly paints a different picture than understanding distractibility in the context of an attention deficit disorder. Qualitative data analysis is discussed in further detail in the final chapter on report writing.

Activity: Types of Questions

Test Yourself

- Why might a qualitative researcher choose an unstructured interview format?

- Why would a qualitative researcher opt for purposive sampling over a probability-based technique?

- Why is it difficult to anticipate the potential risks stemming from a qualitative interview?

- What three techniques are used during interviews to help establish trust and build rapport?

- What is the purpose of a “throw-away” question?

- What does transcription refer to?

- Why is context important to a qualitative researcher?

FOCUS GROUP INTERVIEWING

A focus group is a small discussion group led by a skilled interviewer that is designed to obtain views and feelings about a topic of interest (Krueger & Casey, 2015). Like in-depth interviewing, a focus group is a method for collecting data about people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. What sets a focus group apart from an in-depth interview with multiple participants is the additional creation of whole-group data, which becomes the unit of analysis (Ritchie et al., 2014). For interviews, multiple participants provide independent answers to questions posed by an interviewer. Similarly, individuals in focus groups can provide individual responses that are later examined as participant-based data. However, in a focus group, a moderator creates a small-group discussion and that interactive collaboration also becomes an important source of data collected (Morgan, 1996). Most focus groups consist of between 5 and 10 participants who are selected because they possess certain characteristics in common or are believed to have especially well-informed views on the topic of interest. For example, in advance of a residence being built at a university, focus groups could be conducted with student groups for applied research purposes to learn about the potential impact of a residence on existing campus services. Who better to ask than the primary users of services directed at students and those likely to live in residence? Focus groups can provide insight into how students’ current patterns of service use might change if they lived in residence. For example, participants might indicate that if they lived in an adjacent residence, they would like to be able to access the library after regular hours since they tend to study at night. In addition, they could note that they might be less likely to purchase food to eat on campus, since it would be just as convenient, and now was cost saving to head home between classes to make lunches and snacks. Sometimes focus groups can be extremely beneficial for identifying unanticipated findings. In a focus group I conducted on this topic at the university where I teach, participants identified the need for a special type of “quiet space” or “spiritual room” for prayer on campus. Participants explained that such a space would be especially important for students who pray several times a day.

Like in-depth interviews, focus group topics span an infinite range. When I was seconded from my teaching role by the Office of the Vice President of Resources to serve a two-year term as a resource development planner, I relied heavily upon focus groups to learn more about how students use existing resources and space on campus. I also used focus groups to learn about the ideas and interests of recently retired and soon to be retired faculty and staff members, to see whether and how they might wish to stay connected to their former place of employment. As part of my research on the scholarship of teaching, I’ve led focus groups with students as participants to learn about study strategies and to determine what they perceive to be effective learning practices. I have similarly interviewed instructors in focus groups to discern how they prepare for courses. Focus groups are especially useful for gaining insight into problems, issues, or processes. Examples of topics studied by Canadian researchers using focus groups include the following:

- Sustainable eating behaviours among university students in Canada (Mollaei et al., 2023).

- Utilization of mental health services by new immigrants in Canada (Pandy et al., 2022).

- The experience and needs of provincially incarcerated mothers in Nova Scotia (Paynter et al., 2022).

- Post-secondary student consequences and coding during the COVID-19 pandemic (Morava et al., 2023).

- Barriers to help seeking by men who have experienced abuse in intimate relationships (Lysova et al., 2020).

- How gender norms influenced the experience of women physicians in British Columbia at the start of the pandemic (Smith et al., 2022).

As with an in-depth interview, a focus group is initiated by a skilled interviewer, typically referred to as a moderator or facilitator, who poses questions and attempts to steer an otherwise natural conversation toward the exploration of certain topics. Because the interviewer stands out in a focus group as a moderator who manages group dynamics, leads the group through specific issues and questions, and imposes structure when necessary, a focus group is generally considered to be less natural and more “staged” compared to a one-on-one interview (Morgan, 2001). In addition, participants in focus groups are affected by the presence of others who say things and do things that shift the conversation in directions that might not have occurred had the participants been interviewed individually. This can have positive and negative implications for validity. For example, validity decreases as participants agree with other group members because they think this is the most appropriate response given demand characteristics created by the group. Or, similarly, participants may be unwilling to express divergent viewpoints they possess because they do not want to stand out as being different from the rest of the group (i.e., social desirability bias). Comments made by certain members of the group can also be distracting for other members since they take attention away from what any given individual might have originally stated, had someone else not provided a response first. In other words, listening to one member’s response can mean interrupting the thought pattern or potential response of everyone else. On the other hand, comments made by other group members can trigger ideas for greater innovation, or they may help a participant more fully clarify individual responses in a manner that enhances validity.

Compared to in-depth interviews, focus groups can be a relatively inexpensive, time-efficient means for obtaining rich, detailed information from knowledgeable participants. Because group members usually share common characteristics and have specialized knowledge about the topic of interest, their feedback during the focused discussions can be instrumental in producing novel insights for ways to solve issues or create programs tailored to the needs of a specific group. However, much of the data obtained will largely depend on the skill set of the individual moderator, whose role it is to steer the discussion in such a way to produce and maintain group dynamics that yield the most relevant feedback from the participants. In summarizing the most important characteristics of good moderators, Krueger and Casey (2015) point out that the “right” kind of moderator shows their respect for participants, understands the purpose of the study and the topic, communicates clearly, is open and not defensive, and is able to bring about the most useful information from the group.

Research in Action

Focus Groups: Behind the Glass

Focus Groups: Behind the Glass is a short documentary produced and distributed by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. This video demonstrates the utility of focus groups in marketing for learning about consumer attitudes and views toward products. Go to WorldCat.org and search for “Focus Groups: Behind the Glass” to identify libraries near you that carry a copy of this video.

FOCUS GROUP COMPONENTS

The three most essential elements of a successful focus group are clear objectives, an appropriate group of participants, and a highly skilled moderator.

Clear Objectives

As with any study, a researcher first needs to be clear about the overall purpose and objectives. Like in-depth interviews, a focus group is utilized to learn more about a topic of interest from the perspective of individuals who have first-hand knowledge regarding that process, event, or condition of interest. Beyond an in-depth interview, there is an assumption that through the ensuing discussion, group members will provide a range of views and, ultimately, information and details might emerge beyond what could be obtained in individual interviews.

Participant Groups

Although marketing-based focus groups investigating consumer views often include as many as 12 participants in a session, social researchers recommend 6 to 8 (e.g., Lune & Berg, 2021; Morgan, 2019). If I have a larger potential group (e.g., of 10 or 12 members), I will usually divide it into two separate focus groups (e.g., of 5 or 6 members). However, the actual size of a group is best determined by the overall research purpose and other design considerations, such as the number of potential questions. Krueger and Casey (2015) offer this advice: “If the purpose is to understand an issue or behaviour, invite fewer people. If the purpose is to pilot-test an idea or materials, invite more people” (p. 83). The key is to strike a balance in numbers of participants that will promote discussion and allow the facilitator to fully cover off the main issues in a reasonable time frame, anticipating that some of the members will talk more than others. A study may include three or four different focus groups on the same topic to fully explore the issue (Krueger & Casey, 2015). A good indication that “enough” groups have been utilized is when the facilitator can reasonably anticipate what the next group is going to say about the issues during the ensuing discussion (Bell et al., 2022).

In addition to size, a researcher needs to carefully consider the composition of focus groups. Ideally, the more diverse but homogenous (i.e., alike) a group is, with respect to the relevant characteristic of interest, the better. For example, if a researcher is interested in how instructors prepare for courses they have never taught before, the shared characteristic is new course preparation, but the group could include, for diversity, instructors who teach full time and part time and those with varied teaching experience. Alternatively, if a researcher is interested in how sessional (i.e., part-time) instructors teaching introductory-level courses prepare for classes, the common elements are instructors with limited-term appointments and introductory level courses. In this case, diversity can be achieved by including instructors who meet the criteria and who are from a variety of disciplines (e.g., sociology, anthropology, and political science).

Participants are typically recruited through a letter of invite sent out via email, as a paper copy, in a newsletter, or as a posting in a Facebook group. The letter of invite is usually less formal than a consent form, and it outlines who the researcher is, what the purpose of the study is, what the expectations are for participants, what the participation incentives are (if any), and what the eligibility criteria are (see figure 9.2).

Term Instructor Focus Group

Dear [term instructor’s name],

You are invited to participate in a focus group on teaching preparations.

My name is X and I am an associate professor in the Department of X at X. I am conducting research on teaching introductory X. Since the majority of introductory X courses are taught by term instructors, I would like to learn more about how you go about preparing for your classes and what kinds of resources you find to be useful for instructional purposes.

The focus group will take approximately two hours. If you choose to participate, I will be asking you to comment, as part of an informal discussion with about 5 other term instructors, on a series of questions related to course preparation. For example, I will be asking you if you use any supplementary resources (e.g., an instructor’s manual or test bank), what types of supplementary resources work well for you, and which ones are of little or no value to you. In addition, I will be asking you for any ideas or recommendations you have for resources that might better facilitate introductory level teaching among term instructors.

Note: This study comprises institutional research and was approved by X’s Research Ethics Board. You will be provided with a consent form and agreement to maintain confidentiality at the session.

Date and Time:

Location:

Light refreshments will be included and as a token of appreciation, you will receive a $50 gift certificate.

Eligible participants are individuals who are currently teaching at least one course at X and have taught an introductory level course at least once within the last two years. If you are interested in participating in the focus group, please email me as soon as possible.

Sincerely,

X

X’s email address

Figure 9.2. Sample Letter of Invite

A Skilled Moderator

A moderator “is a trained facilitator used in focus group research who guides the focus group discussion” (Neuman & Robson, 2024, The Focus Group Procedure). A moderator in a focus group is akin to an interviewer in an in-depth qualitative interview. First, a moderator prepares technical and organizational details pertaining to the study. This can include setting up a meeting room (e.g., arranging the chairs so participants can see one another); bringing in refreshments for participants or, at a minimum, providing water for the participants; distributing other necessary materials, such as consent forms and pens; and setting up some type of audio-recording device. An assistant might be included in the session to take some back-up “real-time” notes or to type comments during the session that can later be used to contextualize the transcribed discussion. The main role of a moderator is to welcome the participants, obtain informed consent from the participants, explain the ground rules for the focus group session, get the participants talking, and guide the discussion in a manner that elicits responses from the various participants while covering off the essential questions (Krueger & Casey, 2015). In addition, the moderator helps to establish a positive group dynamic by encouraging equitable participation. For example, a moderator must be able to encourage participation by everyone, even the shy participants or people who seem more reluctant to speak out (e.g., by using prompts, by nodding, and by establishing turn-taking rules). Moreover, just as a skilled instructor leads a classroom discussion so that one student doesn’t predominate, a moderator also needs to incorporate strategies to help foster equitable group dynamics.

Analyzing Focus Group Data

Akin to the way in-depth interview transcripts are coded for themes using qualitative analysis and how messages in the media are coded for prevalent patterns using content analysis (see chapter 8), focus group data is first transcribed and then examined and coded in stages. This process can be extremely time consuming and complex, especially in studies based on several different focus groups. For example, in a study on parents’ and teachers’ views on physical activity and beverage consumption in preschoolers, De Craemer et al. (2013) utilized 24 parent-based focus groups and 18 teacher-based focus groups from six different countries (i.e., Belgium, Bulgaria, Germany, Greece, Poland, and Spain). First, each audio-taped focus group discussion was made available in all six countries, where the focus group discussions were transcribed into written text in the local language of each recipient country. Next, the transcriptions were independently coded, using qualitative content analysis, by local researchers. Following this, the main findings from the focus groups were translated into English and forwarded to two principal researchers (who received a total of six versions of the original data). The principal researchers then assessed and compiled the main findings using a qualitative software program called NVivo (see chapter 12 for more information on this software). Finally, the principal researchers summarized the key findings, along with illustrative quotes and excerpts from the original data, in a report that was verified by the organizers (De Craemer et al., 2013).

One of the more interesting findings from this study was a strong opinion by parents that their preschoolers were sufficiently physically active and that they had healthy beverage intakes (e.g., they drank lots of water and only minimal amounts of sugar-laden drinks such as juices, pop, and chocolate-flavoured milk). The parental perspective was not consistent with the conclusions substantiated in the previous literature by more objective methods (e.g., dietary records), suggesting that parents may need more information about existing dietary practices if they are to be motivated to make changes in their own families.

Activity: Focus Groups Review

Test Yourself

- What is a focus group?

- In what ways does a focus group differ from a qualitative interview?

- How might the presence of others increase validity in a focus group?

- Why would a researcher run multiple focus groups on the same topic?

- In what ways is focus group composition important?

- What is the role of a focus group moderator?

CHAPTER SUMMARY

- Explain what a qualitative interview is.

A qualitative interview is a technique that is designed to help a researcher understand aspects of the social world from the perspective of the participant who is experiencing them. - Describe the structure of qualitative interviews and explain why qualitative interviewing is “responsive.”

A semi-structured interview is somewhat flexible since questions can be modified and clarified, while an unstructured interview is highly flexible, enabling questioning to develop as a function of exchanges within the interview itself. Qualitative interviewing is responsive because an interviewer asks questions and probes for details based upon what is being said during the interview, rather than just asking questions that are prepared in advance. - Identify and explain important considerations that arise in the main steps for conducting a qualitative interview.

First, a qualitative researcher needs to adopt the most appropriate interview format and try to obtain the most suitable interviewees. In addition, a researcher needs to anticipate potential risks to participants. Since the interviewee is not anonymous, a researcher needs to take special precautions to uphold confidentiality. The interviewer also plays an important role as the research instrument, establishing trust, motivating the interviewee to provide detailed information, and carefully steering the interview in the desired direction. - Define and differentiate between main question types.

An icebreaker is an opening statement that is used specifically in order to establish rapport. An essential question is one that exclusively concerns the central focus of the study. Probes are used to motivate an interviewee to continue speaking. Throw-away questions are unrelated to the research and are used to give the interviewee a break. Extra questions are equivalent to essential questions and help to assess reliability. Follow-up questions are specific to comments and are used to clarify main ideas. Closing questions bring the interview to an end by re-establishing distance. The final question asks if the participant has any questions about the study or any further comments to make. - Define focus group and compare focus groups to in-depth interviews.

A focus group is a small discussion group led by a skilled interviewer called a moderator. A focus group is somewhat more structured or staged relative to an in-depth interview, and group dynamics can influence individual responses, so they end up different from how someone would normally respond in a one-on-one interview. Focus groups are a relatively inexpensive and efficient means for gaining rich, detailed information from an informed group who likely has first-hand experience with the topic of interest. A disadvantage of a focus group is that the quality of information obtained can be negatively affected by an inexperienced or unskilled moderator. - Describe the main components of a focus group.

The three essential components of a focus group are clear objectives, an appropriate group of participants, and a skilled moderator.

RESEARCH REFLECTION

- Suppose you are interested in conducting an exploratory study into what it would be like to be married to more than one spouse at the same time (i.e., polygamous or plural marriage). Would an in-depth interview be the most suitable technique for your research project? Why or why not?

- Develop an interview guide that you could use if you were going to interview a sample of your classmates about their views on and use of ChatGPT.

- Identify a topic you think would be best addressed using a focus group. Explain your rationale. If you were the moderator for the focus group, what are three essential questions you would ask the group about the topic? Provide one example of an icebreaker you could use to start the session.

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE

Objective: To learn how to conduct a focus group

Directions:

- Suppose you want to learn more about effective study strategies using a focus group.

-

- First, enlist five or six of your classmates.

- Next, assign the role of moderator to one member of your group. Also ask for a volunteer to take notes while the group discusses study strategies.

- Come up with four essential questions that would help us learn about study strategies.

- Identify strategies your group would use to establish rapport and maintain good group dynamics.

-

- Try running a 20-minute focus group with the selected moderator as the facilitator.

- Describe your main findings.

- How would you improve upon the focus group if you were going to repeat this topic using a different group of participants?

RESEARCH RESOURCES

- To learn more about qualitative interviewing, see Edwards, R., & Holland, J. (2023). Qualitative interviewing: Research methods. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- For an online guide to interviewing, check out Armchair Academic’s Qualitative interviews: A how-to guide to interviewing in the social sciences on YouTube posted on Sept 19, 2021.

- For information on how to design and conduct a focus group, see Acocella, I., & Cataldi, S. (2020). Using focus groups: Theory, methodology, practice. Sage.

- For more advanced topics, such as using focus groups in a cross-cultural context and online focus groups, refer to Morgan, D. L. (2019). Basic and advanced focus groups. Sage.

- To find out how Western focus groups and Indigenous learning circles have been blended in research, see Hunt, S. C., & Young, N. L. (2021). Blending Indigenous sharing circle and Western focus group methodologies for the study of Indigenous children’s health: A systematic review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20(2), 1–16.

A technique used to understand the world from the subjects’ point of view, to unfold the meaning of their experiences, and to uncover the world prior to scientific explanations.

A somewhat flexible interview format in which main questions are prepared ahead of time but the questions can be modified or clarified based on participant feedback.

A highly flexible interview format based on questions that develop during the interaction as a result of participant feedback.

A series of key questions that provide the framework for an interview.

A technique in which the interviewer demonstrates an understanding of what is being said and expressed through appropriate feedback.

An opening question that is used specifically to establish rapport.

Statements that move the conversation into the essential questions.

Questions that exclusively concern the central focus of the study.

Questions used to motivate an interviewee to continue speaking or to elaborate on a topic.

Questions unrelated to the research topic that are used to take breaks in the conversation.

Questions roughly equivalent to essential ones that are used to assess reliability.

Questions specific to comments made that are used to clarify main ideas.

Questions used to bring closure to the interview by re-establishing distance between the interviewer and interviewee.

The last interview question, in the form of a general inquiry to determine if the participant has any questions about the study or further comments to make.

A data-entry process in which the obtained verbal information is transferred verbatim into text.

A complicated notion that locates and explains action-interaction within a background of conditions and anticipated consequences.

A small discussion group led by a skilled interviewer that is designed to obtain views and feelings about a topic of interest through group interaction.

A trained facilitator used in focus group research who guides the focus group discussion.