Timeline of English (page)

The following is the original learning content about the timeline of English; later it was presented in a Timeline H5P object. See the final version on the previous page.

Familiarize yourself with the following timeline of English, including the information/content details provided within the timeline (i.e., you must click on each of the cells to read the details provided and familiarize yourself with them):

Linguistic Periods

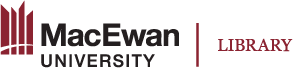

Proto-Indo-European

The homeland for the Proto-Indo-European people is thought to have been in modern-day eastern Ukraine and southern Russia, just northeast of the Black Sea.

From here, they migrated north and westward, throughout Europe, and south and eastward across central Asia and all the way to present-day northern India.

Proto-Celtic and Proto-Germanic

As groups of the Proto-Indo-Europeans settled different lands and others continued on their migration, the common language originally spoken by these people started to evolve into numerous different varieties. The tribes who settled in central and northern Europe spoke Proto-Germanic.

Proto-Celtic was spoken by the tribes who continued their migration to the western periphery of the continent and on to what is now called the British Isles.

Celtic

In the first millennium B.C.E., Proto-Celtic split into a variety of distinct languages.

Original versions of the following languages were spoken in distinct regions: Irish was spoken in Ireland, Scots Gaelic in Scotland, Welsh in Wales, Cornish in southwestern Britain, and Manx on the Isle of Man.

Germanic

Around 1000 B.C.E., Proto-Germanic differentiated from other Indo-European languages in its pronunciation of certain sounds, which has been called the First Sound Shift.

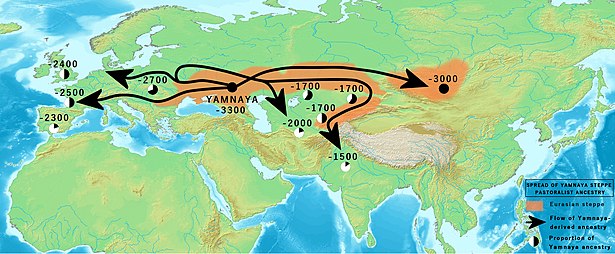

The Germanic languages spoken on the western periphery of the continent formed a group called the West Germanic Branch, spoken by the Angles, the Saxons, the Jutes, and the Frisians, who went on to invade Britain beginning around 449 C.E. (see Anglo Invasion of Britain).

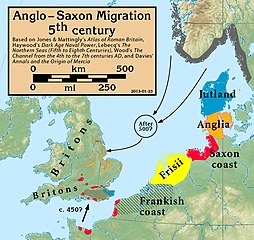

The Germanic languages spoken in modern-day Scandinavia formed a group called North Germanic, spoken by the Vikings (Norse) who invaded Britain a few centuries later, around 793 C.E. (See Viking Invasion of Britain).

Old English

From 449 C.E. to 1100 C.E., waves of invasion, migration, and settlement of Germanic tribes from modern-day Denmark and Germany (the Angles, the Saxons, the Jutes, and the Frisians) pushed the Celtic-speaking people to the outlying regions of Britain (Cornwall, Wales, Scotland) and established the Anglo-Saxon people as the main population in Britain. (See the Anglo Invasion of Britain.)

The language (which was constantly changing and evolving) spoken by these people is called Anglo-Saxon, and it formed the base for Old English.

The Norse people from modern-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, who spoke North Germanic languages, started to invade Britain in the late eighth century. They settled in the north and east of Britain. (See Viking invasion of Britain.)

Due to the influence of the Norse languages, the vocabulary of Old English was expanded (with the addition of sk words like sky, skin, skill, and skirt, for example) and the complicated system of inflectional endings on nouns and verbs was simplified or levelled.

Middle English

The Middle English period lasted from 1100 C.E. to 1500 C.E.

The biggest change in the language came about from the influx of French vocabulary introduced by the French-speaking ruling and upper classes for the few centuries after the Norman invasion.

Some characteristics of the language were the thou series of pronouns being used as well as simple negation and interrogation.

The Great Vowel Shift had begun (but not ended) and the printing press had been invented, which led to some spelling standardization.

Modern English or Present-Day English

Modern English dates from 1650 to the present day.

Modern English is an international language used as a first or second language throughout the world. (See World Englishes.)

The People and Main Events

European Copper Age

The Copper Age was a transitional period between the Stone Age (when most tools were made of stone) and the Bronze Age (when tools were instead made of certain metals, especially bronze). In the Copper Age, stone tools were used alongside early metal ones, often made of copper.

In Europe, the Copper Age lasted for a period sometime in the fourth millennium B.C.E. (that is, sometime between 4000 B.C.E. and 3000 B.C.E.).

Celtic Tribes Reach Britain

Celtic tribes had reached and settled in Britain, including modern-day Ireland, by the late Iron Age, sometime around 300 B.C.E. (which was the period of maximum Celtic expansion).

Roman Empire Reaches Britain

The main Roman invasion of Britain took place in 43 C.E., although, prior to that, smaller incursions had taken place and certain trading and diplomatic relationships had been established between Roman forces and outposts and the Celtic peoples of southern Britain.

Roman forces took control of all of present-day England and Wales but never reached present-day Ireland or Scotland.

In fact, the Romans gave up trying to conquer the Pictish and Celtic tribes in that region, so they built Hadrian’s Wall (starting around 122 C.E.) to contain them in the north.

Some Roman soldiers settled in Britain and intermarried with the local Celtic population. They formed a distinct society and called themselves Britons (hence the land was called Britain).

Anglo-Invasion of Britain

Waves of invasion and migration of several Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians) from present-day southern Denmark and northern Germany began around 449 C.E.

By this time, the bulk of Roman military hierarchy had abandoned Britain, leaving the people in Britain with no defences and allowing the Germanic tribes to take control of the island fairly easily.

The word English comes from Angles (hence the land came to be called England).

Viking Invasion of England

Starting in about 793, Viking tribes from present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden began invading the eastern shores of Britain.

A type of peace treaty, the Danelaw was established in 878 and restricted the region in which the Norse invaders were allowed to settle.

Eventually, many of these Scandinavian people settled in Britain and intermarried with the local Anglo-Saxon population thus changing how the language developed in the Old English period.

Norman Invasion of England

In 1066, William the Duke of Normandy (north-central France) and his Norman forces invaded; William the Conqueror, as he came to be known, took the throne as the King of England.

The Normans took control of all government, administration, and church affairs, thus introducing many French words into the vocabulary of English.

French was the main language of the ruling and upper classes for almost four centuries, until the end of the Hundred Years’ War.

Imperialism and Colonization; Discovering New People

The years from 1500 to the early 1900s marked a period of exploration, domination, and colonization for England.

England started by establishing plantations in parts of Ireland before extending its reach across the Atlantic and colonizing parts of North America.

Imperial expansion also took place to the east with colonization of Indonesia and India, and eventually to the South Pacific, primarily Australia.

In the late 1800s to early 1900s, England colonized many regions in Africa.

Today’s Commonwealth is a grouping of 53 independent nations, most of which were once British colonies.

Global Communications and Interdependence

Modern technology allows for fast and cheap global communications.

Just as ideas, products, and commodities are being shared between nations, so are words!

English has borrowed words from all over the globe just as other languages are borrowing English words to talk about our modern world.

Inward Influx of Peoples/Languages

For the first several thousands of years in which people have inhabited the British Isles, much of the linguistic change has been the result of waves of different people migrating to and/or invading the islands (for example, Celts, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Vikings, Normans).

Outward Expansion and Contact with Societies Around the Globe

For the last 500 years much of the new vocabulary has been due to English-speaking people exploring, conquering, and colonizing places all around the globe.

As these speakers encountered new societies, new animals, new foods, new technologies, and so forth, they needed words to talk about these objects, so they often borrowed the words that the local populations used.

Other Key Events

The Birth of Christ

This event is important for the development of English because, in the fourth century, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire.

Even after the withdrawal of Roman forces from Britain, Christian monasteries were established through the support of Rome in an effort to convert the inhabitants of the British Isles to Christianity.

All of the proceedings of the Church were carried out in Latin. Monasteries were also places of education, thus many Latin religious and educational terms entered the language.

Roman Withdrawal from Britain

By around 410 all Roman troops had left Britain to fight battles on the continent, leading up to the eventual fall of the Roman Empire.

Danelaw Established

In 878, Anglo-Saxon king Alfred the Great defeated the Vikings and established a region in which they were to live and peacefully coexist with the English.

The Black Death

The Black Death (bubonic plague) spread through Europe in the late 1340s and reached England around 1348.

It killed a quarter to a third of Europe’s population in the years 1347 to 1350.

England was particularly harshly hit, with 70 percent of the population dying.

England’s pre-plague population was around 7 million by 1400, the population was only 2 million.

Numerous but less devastating outbreaks of the bubonic plague continued to torment Europe until the 1700s.

England’s social structure was greatly affected with the peasant classes gaining upward mobility due to the labour shortage and more available land.

As a result, classes were intermingling much more, which is one suggestion for why the Great Vowel Shift occurred.

Printing Press

Around 1440, Johann Gutenberg invented the printing press in Germany, and it was soon reproduced throughout Europe.

The printing press allowed for mass production of written text. This resulted in

- a much larger percentage of the population becoming literate

- beginning of the standardization of spelling systems.

Hundred Years’ War

The Hundred Years’ War was actually a series of wars between the House of Valois (based in France) and the Plantagenets (ruling in England) who were battling for the French throne.

The wars lasted just over 100 years (from 1337 to 1453).

The House of Valois won the war for the throne of France, and the Plantagenets were expelled from France.

Afterwards, the close contact that had been maintained between England and France since the Norman Invasion came to an end, and nationalistic sentiments took hold.

English replaced French as the main language of the ruling and upper classes in England.

English Renaissance and the Age of Exploration

The English Renaissance began in the early 1500s and was a period of great cultural and artistic growth.

During the Age of Exploration, which lasted until the early 1700s, many nations in Europe, including England, explored the world by sea in search of trade goods and trading partners.

These periods led to a tremendous enhancement of knowledge that was accompanied by vast expansion of the English vocabulary.

Language Characteristics

The First Sound Shift

When Proto-Germanic evolved from Proto-Indo-European during the first millennium B.C.E., one of the big changes was in the pronunciation of certain consonants (which marks today’s Germanic languages as different from other Indo-European languages).

In 1822, Jakob Grimm (of Grimm’s fairy tales) hypothesized this change and called it the First Sound Shift.

Here are some examples from English (a Germanic language), Latin, and French (both Romance Languages) to demonstrate the difference.

| Sound change | English | Latin | French |

| [d] to [t] | tooth | dentis | dent |

| [k] to [h] | heart | cord- | coeur |

| [p] to [f] | fish | piscis | peche |

Highly Inflected

Like German, its modern Germanic-language cousin, Anglo-Saxon had a system of endings, or suffixes, placed on noun and verb roots that conveyed grammatical information.

On nouns, the endings would indicate what role the noun played in the sentence (for example, was it the subject, the direct object, the indirect object?, etc.).

On verbs, the endings would indicate information about the subject (such as the number and person of the subject), about the verb itself (such as weak versus strong) and about the event (past, present, future, subjunctive, and so forth).

Since nouns and verbs carried so much information about their relationship within the sentence, speakers did not need to rely on word order to establish those relationships.

For example, in Modern English the noun acting as the subject almost always comes in front of the verb and the noun acting as the object almost always comes after the verb.

The toddler (subject) hugged (verb) the dog (object).

Mixing up the order does not make sense in Modern English (*hugged the dog the toddler) but would have been fine in Old English.

Grammatical Simplification

Anglo-Saxon was a highly inflected language.

As the Anglo-Saxon populations and the Norse populations began to interact and intermarry, the Anglo-Saxon language lost many of its complicated inflectional endings that marked grammatical information.

This type of change is called levelling (simplification due to languages mixing).

Instead, the word order in sentences became more rigid as a way to indicate which nouns were acting as the subject or the object of a sentence.

Compounding

One trait of Old English, similar to other Germanic languages, was the tendency to put two pre-existing words together to form a compound when a new word was required.

For example, the Old English word for dawn was doegred, which is a compound of day and red.

Pronouns

The pronouns thou, thee, thy, and thine were used for second-person singular (where we use you, you, your, yours today).

Simple Negation and Interrogation

Asking questions (the interrogative structure) and negating a statement (the negative structure) were done without the assistance of an auxiliary verb such as do.

“Goest thou to market?”

“I go not.”

Influx of French Vocabulary

From the Norman invasion of England in 1066 to the end of the Hundred Years’ War in 1453, the ruling and upper classes in England spoke French and had very close political and economic ties with France. As a result, many French words entered the vocabulary of the general public as well, especially in domains such as government and administration (for example, citizen and salary) and high society (such as, servant and royal).

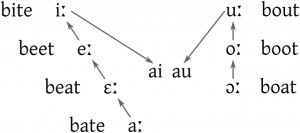

The Great Vowel Shift

Starting sometime in the 13th century, English speakers started to change the way they pronounced many of the vowels in their language.

By around 1600 this sound shift had stabilized with the result that certain English vowels are pronounced quite differently than vowels of other European languages.

For example, in Italian the letter i is pronounced [i], whereas in English it is pronounced [aj] / [aI].

The shift was quite systematic in that speakers tended to pronounce the vowels with a higher jaw/tongue position than they had previously done.

The examples below demonstrate pre- and post-shift pronunciation of certain words.

| name | [nam] to [nem] |

| see: | [se] to [si] |

| moon: | [mon] to [mun] |

The tense vowels that were previously pronounced with the jaw/tongue in the highest position (that is, [i] and [u]) were turned into diphthongs pronounced with a low jaw/tongue.

| time | [tim] to [tajm] |

| house | [hus] to [haws] |

Certain words resisted the shift:

| shift: | meat to [mit] |

| no-shift: | great to [gret] |

| break to [brek] |

Since much of the spelling standardization of English occurred before the Great Vowel Shift had finished and since not all words underwent the shift, Modern English has, as a result, a very inconsistent and tricky spelling system.

In Scotland, the degree of vowel shift was quite different, which is one of the reasons why the Scottish accent is distinct.

Spelling Standardization

After the invention of the printing press, the spelling system of English gradually became much more standardized (as opposed to people spelling words according to their own particular accent or preference).

Much of the standardization happened before the end of the Great Vowel Shift. This resulted in some words being spelled, even today, very differently than they are pronounced.

The publication, in 1755, of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language also aided in standardizing the spelling of English.

Vocabulary Expansion; Discovering New People

The size of the English vocabulary exploded during the Early Modern and Modern English periods out of necessity to accommodate all the new ideas and objects that English speakers encountered during years of the English Renaissance and the Age of Exploration, followed by the periods of Imperialism and Colonization.

Words were borrowed from all corners of the globe and incorporated into the English language.

Complex Negation and Interrogation

By the Modern English period, negation and interrogation had evolved to today’s complex structure that requires the involvement of one of the main auxiliary verbs: to be, to have, or to do.

To negate a sentence, the negative word is placed immediately after the auxiliary verb (bolded):

| I am going to school. | becomes | I am NOT going to school. |

| I have seen this movie. | I have NOT seen this movie. | |

| I like ice cream. | I do NOT like ice cream. |

Notice that if the basic declarative sentence (a sentence that makes a statement) does not contain an auxiliary verb, the ‘dummy’ auxiliary do is inserted.

To make an interrogative sentence (one that asks a question) out of a declarative, the positions of the subject and the auxiliary verb are reversed:

| The student is walking to school. | becomes | Is the student walking to school? |

| You have seen this movie. | Have you seen this movie? | |

| They like ice cream | Do they like ice cream? |

Notice again that the dummy auxiliary do is required if the basic declarative sentence does not already contain an auxiliary verb.

The Big Mix

Today’s English is a “big mix” of influences from many different languages over the years.

English is still considered to be a Germanic language, since the foundation of the language in terms of its basic grammatical structure and its basic vocabulary is Germanic in origin.

For example, of the 1,000 most common words in English, 83 per cent are of Germanic origin whereas only 11 per cent are of French origin.

However, of the English extended vocabulary, French has been a huge impact on English and, to a lesser extend, so has Latin (via the Church and scientific terms during the Renaissance and beyond).

For example, of the second 1,000 most common words in English, only 43 per cent are Germanic whereas 46 per cent are French and 11 per cent are Latin.

Today, English contains many words borrowed from all over the globe:

For example, tattoo is a Polynesian word, alcohol is an Arabic word, kindergarten is a German word, kayak is an Inuit word, and shampoo comes from the Indian subcontinent.

World Englishes

Today, English is spoken as a first language in countries all over the world, with numerous different dialects (we will discuss this further in the next module).

It is also the language spoken most often as a second language, which allows it to be a lingua franca (a common language that allows native speakers of different languages to communicate without the use of translators).

Two negative consequences of English as a global and dominant language is that some indigenous languages are becoming extinct, and people who do not speak English are at a disadvantage if they want to participate in business or politics at a global level.

Beowulf

Beowulf is a heroic epic poem written sometime between the eighth and eleventh centuries (during the Old English period).

Beowulf is the name of the hero who battles three formidable foes before falling to defeat.

The poem was written in Old English, although the events take place in Scandinavia.

Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (1340 to 1400) is probably the most famous writer of the Middle English period. He is the author of Canterbury Tales.

King James Bible, Shakespeare

King James Bible

The King James Bible was published in 1611.

It is largely based on a translation of the Bible by William Tyndale in 1525.

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare (1564 to 1616) is the author of numerous plays and poems written between 1590 to 1613.

He is largely regarded as England’s most famous playwright if not the greatest writer in English.

John Milton; Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language

John Milton

John Milton wrote Paradise Lost in 1667.

It is considered one of the greatest works in the English language.

Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language

The first extensive English dictionary was written by Samuel Johnson and was published in 1755.

One result of its publication was increased standardization of spelling in English.

Romanticism; Victorian; Modernism; and Post-Modernism

Romanticism

The Romantic period occurred during the mid-1700s to mid-1800s.

It was a reaction to the Industrial Revolution: back to nature and instinct was regarded as being superior to the machine and civilization.

Famous Romanic writers include:

- Sir Walter Scott

- Mary Shelley

- Jane Austen

- William Blake

- Oscar Wilde

- William Wordsworth

- John Keats

Victorian

The Victorian era lasted from 1837 to 1901.

The novel was the main literary form.

Authors could write for the public as opposed to for an aristocratic patron; they could suit the tastes of the common person.

Famous Victorian writers include:

- Bronte sisters

- George Elliot

- Charles Dickens

- Thomas Hardy

- Robert Louis Stevenson

- Lewis Carroll

Modernism

The Modernist period was the first half of the 20th century, to the 1970s.

Modernism was a reaction to conservative Victorian attitudes of absolute truths and values.

Famous Modernist writers include:

- James Joyce

- William Butler Yeats

- Joseph Conrad

- Virginia Woolf

- T. S. Eliot

- Ernest Hemingway

Post-Modernism

The Post-Modern period began in the late 1970s.

Post-Modernism absorbed the avant-garde values of and was a reaction to Modernism.

Some famous Post-Modern writers include:

- William Burroughs

- Kurt Vonnegut

- John Barth

- Don DeLillo

- Kathy Acker

- Paul Auster

- Thomas Pynchon

Content adapted from the “Introduction to Human Language” course by MacEwan University in association with the MacEwan Centre for Teaching and Learning.