2.2 Perception Process

Learning Objectives

- Define perception

- Explain the three stages of the perception process.

- Describe the relationship between interpersonal communication and perception.

Perception

Many of our problems in the world occur due to perception, or the process of attending to, organizing, and interpreting the information that comes in through your five senses (Wertz, 1982). Although perception is a primarily cognitive and psychological process, how we perceive the people and objects around us affects our communication. We respond differently to an object or person we perceive favourably than we do to something or someone we find unfavourable (Wertz, 1982). But how do we filter a vast amount of incoming information, organize it, and make meaning from the things that make it through our perceptual filters and into our social realities?

It is easier to make a concrete decision when we have all the facts. We have to rely on our perceptions to understand the situation. In this section, you will learn tools to help you understand perceptions and improve your communication skills. As you will see in many of the illustrations on perception, people can see different things. In some pictures, some might only be able to see one image, but others may see both images, and a small number of people might be able to see something completely different from others.

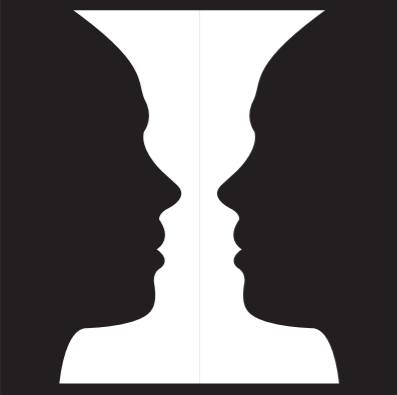

Many famous artists over the years have played with people’s perceptions. The three figures below exemplify three artists’ use of twisted perceptions. Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin initially created the first, commonly called The Rubin Vase. Essentially, you have what appears to be either a vase (the white part) or two people looking at each other (the black part). This simple image is both two images and neither image simultaneously. The second work of art is Charles Allan Gilbert’s (1892) painting “All is Vanity.” In this painting, you can see a woman sitting and staring at herself in the mirror. At the same time, the image is also a giant skull. Lastly, we have William Ely Hill’s (1915) “My Wife and My Mother-in-Law,” which may have been loosely based on an 1888 German postcard. In Hill’s painting, you have two images, one of a young woman and one of an older woman. The painting was initially published in an American humour magazine called Puck. The caption “They are both in this picture — find them” ran alongside it. These visual images are helpful reminders that we don’t always perceive things the same way as those around us. There are often multiple ways to view and understand the same events.

In interpersonal communication, you present a side of yourself each time you talk to other people. Sometimes this presentation accurately represents yourself, and other times it may be a false version of yourself. People present themselves in how they want others to see them. Some people present themselves positively on social media with beautiful relationships. Then, their followers or fans are shocked to learn that those images are inaccurate. If we only see one side of things, we might be surprised to learn that things are different.

Attending

We take in information through all five senses, but our perceptual field (the world around us) includes so many stimuli that our brains cannot process and make sense of it all. So, as information comes in through our senses, various factors influence which stimuli or information continues through the perception process (Fiske & Taylor, 1991).

The first step of the perception process is to select the information you want to pay attention to or focus on, which is called attending. You will pay attention to things based on their look, feel, smell, touch, and taste. At every moment, you are obtaining a large amount of information. So, how do you decide what you want to pay attention to and what you choose to ignore? People will tend to pay attention to things that matter to them. Usually, we pay attention to things that are louder, larger, different, and more complex than we ordinarily view.

When we focus on a particular thing and ignore other elements, we call it selective perception. For instance, when you are in love, you might pay attention to only that special someone and not notice anything else. The same happens when we end a relationship and are devasted; we might see how everyone else is in a great relationship, but we are not.

You pay attention to certain things more than others for several reasons. We first pay attention to something because it is extreme or intense. In other words, it stands out of the crowd and captures our attention, like a beautiful person at a party or a big neon sign in a dark, isolated town. We cannot help but notice these things because they are exceptional or extraordinary in some way.

Second, we will pay attention to things that are different or contradicting. Commonly, when people enter an elevator, they face the doors. Imagine if someone entered the elevator and stood staring at you with their back to the elevator doors. You might pay attention to this person more than others because the behaviour is unusual. It is something you do not expect, making it stand out more. On another note, different might also mean something you are not used to or no longer exists for you. For instance, if someone very close to you passes away, you might pay more attention to that person’s loss than anything else. Some people grieve for an extended period because they are so used to having that person around, and things can be different when you do not have them to rely on or ask for input.

Third, we pay attention to something that constantly repeats. Think of a catchy song or a commercial that continually repeats itself. We might be more alert to it since it repeats, compared to something only said once.

The fourth thing that we will pay attention to is based on our motives. One motive might be to lose weight, and you might pay more attention to exercise advertisements and food selection choices compared to someone who does not have the motive to lose weight. Our motives influence what we pay attention to and what we ignore.

The last thing that influences in the selection process is our emotional state. If we are in an angry mood, we might be more attentive to things that make us angrier. If we are in a happy mood, we will be more likely to overlook a lot of negativity because we are already excited. Selecting involves more than just paying attention to specific cues. It also means that you might be missing other things. For instance, people in love will think their partner is fantastic and overlook many flaws. This is expected behaviour. We are so focused on how wonderful they are that we often neglect the other negative aspects of their behaviour.

We also tend to pay attention to salient information. Salience is the degree to which something attracts our attention in a particular context. The thing attracting our attention can be abstract, like a concept, or concrete, like an object. For example, a bright flashlight shining in your face while camping at night is sure to be salient. The degree of salience depends on three features (Fiske & Tayor, 1991). We find visually or aurally stimulating salient things that meet our needs or interests. Lastly, expectations affect what we find salient.

Organizing

Think again about the three images above (2.2.2-2.2.4). What were the first things that you saw when you looked at each picture? Could you see the two different images? Which image was more prominent? When we examine a picture or image, we organize it in our head to make sense of it and define it. This is an example of perceptual organization. After we select the information we are paying attention to, we have to make sense of it in our brains. This stage of the perception process is referred to as organization. We must understand that information can be organized in different ways. After we attend to something, our brains quickly want to make sense of this data. We quickly want to understand the information we are exposed to and organize it in a way that makes sense.

There are four types of schemes that people use to organize perceptions. First, physical constructs classify people (e.g., young/old, tall/short, big/small). Second, role constructs are social positions (e.g., mother, friend, doctor, teacher). Third, interaction constructs are the social behaviours displayed in the interaction (e.g., aggressive, friendly, dismissive, indifferent). Fourth, psychological constructs are the communicators’ dispositions, emotions, and internal states of mind (e.g., depressed, confident, happy, insecure). We often use these schemes to understand and organize our received information. We use these schemes to generalize others and to classify information.

Let us pretend you came to class and noticed that one of your classmates was wildly waving their arms at you. This will most likely catch your attention because you find this behaviour strange. Then, you will try to organize or make sense of what is happening. Once you have organized it in your brain, you must interpret the behaviour.

Interpreting

Although selecting and organizing incoming stimuli happens quickly and sometimes without conscious thought, interpretation can be a more deliberate and conscious step in perception (Vannuscorps & Caramazza, 2016). Interpretation is the third part of the perception process, in which we assign meaning to our experiences using mental structures known as schemata. Schemata are like databases of stored, related information that we use to interpret new experiences. We all have relatively complicated schemata developed over time as small information units combine to make more complex information. So, you must interpret the situation after you select information and organize things in your brain. As discussed in the example above, your friend waves their hands wildly (attending), and you are trying to figure out what they are communicating to you (organizing). You will attach meaning (interpreting). Does your friend need help and is trying to get your attention, or does your friend want you to watch out for something behind you?

We have an overall schema about interpreting experiences with teachers and classmates. Based on what parents, peers, and the media told us about the school, this schema developed before we went to preschool. For example, you learned that certain symbols and objects like an apple, a ruler, a calculator, and a notebook are associated with being a student or teacher. You learned new concepts such as grades and recess and engaged in new practices such as doing homework, studying, and taking tests. You also formed new relationships with teachers, administrators, and classmates. Your schema is adapted to the changing environment as you progress through your education. Whether schema reevaluation and revision is smooth or troubling varies from situation to situation and person to person. For example, when faced with new expectations for behaviour and academic engagement, some students adapt their schema relatively quickly as they move from elementary to junior high to high school and college. Other students adapt slowly, and holding onto their old schema creates problems as they try to interpret new information through old, incompatible schema.

It is essential to be aware of schemata because our interpretations affect our behaviour (Rumelhart, 2017). For example, suppose you are doing a group project for class and think a group member is shy based on your schema of how shy people communicate. In that case, you may refrain from giving them presentation responsibilities in your group project because you do not think shy people make good public speakers. Schemata also guide our interactions, providing a script for our behaviours. We know, in general, how to act and communicate in a waiting room, in a classroom, or on a first date. Scholars have identified some factors that influence our interpretations:

Personal Experience

First, personal experience impacts our interpretation of events. What prior experiences have you had that affect your perceptions? Maybe you heard from your friends that a particular restaurant was excellent, but when you went there, you had a horrible experience and decided never to return. Even though your friends might try to persuade you to try it again, you might be inclined not to go because your experience with that restaurant was not good.

Involvement

Second, the degree of involvement impacts your interpretation. The more involved or deeper your relationship is with another person, the more likely you will interpret their behaviours differently than someone you do not know well. For instance, let’s pretend you are a manager, and two of your employees come to work late. One worker is your best friend, and the other is someone who just started, and you do not know well. You are more likely to interpret your best friend’s behaviour more altruistically than the other worker because you have known your best friend for longer. Besides, since this person is your best friend, this implies that you interact and are more involved with them compared to other friends.

Expectations

Third, our expectations can impact our sense of other people’s behaviours. For instance, you might expect this to be true if you overheard some friends talking about a mean professor and how hostile they are in class. Let’s say you meet the professor and attend their class; you might still have certain expectations about them based on what you heard. Even those expectations might be completely false, and you might still expect those allegations to be true.

Assumptions

Fourth, there are assumptions about human behaviour. Imagine you are a personal fitness trainer. Do you believe that people like to exercise or need to exercise? Your answer to that question might be based on your assumptions. If you are a person who is inclined to exercise, then you might think that all people like to work out. However, if you do not want to exercise but know that people should be physically fit, you would more likely agree with the statement that people need to exercise. Your assumptions about humans can shape the way that you interpret their behaviour. Another example might be that if you believe that most people would donate to a worthy cause, you might be shocked to learn that not everyone thinks this way. When we assume that all humans should act a certain way, we are more likely to interpret their behaviour differently if they do not respond in a certain way.

Relational Satisfaction

Fifth, relational satisfaction will make you see things very differently. Relational satisfaction is how satisfied or happy you are with your current relationship(s). If you are content, you are more likely to view all behaviours as thoughtful and kind. However, if you are unsatisfied with your relationship(s), you are more likely to view their behaviour as distrustful or insincere.

Past Experiences

If you have had a good experience with a certain company, everything they do is terrific. However, if your first experience was horrible, you may think they are always horrible. In turn, you will interpret that company’s actions as justified because you have already encountered a horrible experience.

Knowledge of Others

If you know someone close to you has a health problem, it will not be a shock if they need medical attention. However, it would be a complete surprise if you did not know this person was unhealthy. How you interpret a situation is often based on what you know about certain situations (Adler et al., 2013).

Watch the following video to understand better how the brain constructs your perception.

Watch: Perceiving is Believing

Video Transcript (see Appendix B 2.2)

Key Takeaways

- Perception is the process of attending to, organizing, and interpreting information. This process affects our communication because we respond to stimuli differently (whether they are objects or persons) based on how we perceive them.

- Given the massive amounts of stimuli taken in by our senses, we select only a portion of incoming information to organize and interpret. We select information based on salience. We tend to find visually or aurally stimulating salient things and things that meet our needs and interests. Expectations also influence what information we select.

- We then organize the selected information using proximity, similarity, and patterns.

- We interpret information using schemata, allowing us to assign meaning based on accumulated knowledge and previous experience.

Exercises

- Take a moment to look around wherever you are right now. Take in the perceptual field around you. What is salient for you at this moment and why?

- We simplify and categorize information into patterns as we organize information (sensory information, objects, and people). Identify some cases in which this aspect of the perception process is beneficial. Identify some cases in which it could be harmful.

- Think about some of the schemata you have that help you make sense of the world around you. For each of the following contexts — academic, professional, and personal — identify a schema you commonly rely on or think you will rely on. For each schema you identified, note a few ways that it has already been challenged or may be challenged in the future.

References

Adler, R., Rosenfeld, L. B., & Proctor, R. F., II. (2013). Interplay: The process of interpersonal communication. Oxford.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Rumelhart, D. E. (2017). Schemata: The building blocks of cognition. Routledge.

Vannuscorps, G., & Caramazza, A. (2016). Typical action perception without motor simulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(1), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516978112

Wertz, F. J. (1982). The findings and value of a descriptive approach to everyday perceptual process. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 13(2), 169–195. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916282X00055

Image Attributions

Figure 2.2.1. It’s All About Perception by Libre Texts. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.2.2 The Facevase by Edgar Rubin. In the public domain.

Figure 2.2.3. All is Vanity by Charles Allan Gilbert. In the public domain.

Figure 2.2.4. My Wife and My Mother-in-Law by William Ely Hill. In the public domain.

Media Attribution

CrashCourse. (2014, March 17). Perceiving is believing: Crash course psychology #7 [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n46umYA_4dM

Attribution Statement

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. (2013). Communication in the real world [Adapted]. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.