4.1 Principles and Functions of Nonverbal Communication

Learning Objectives

- Compare and contrast verbal communication and nonverbal communication.

- Discuss the principles of nonverbal communication.

- Provide examples of the functions of nonverbal communication.

All five senses can take in nonverbal communication. Health professionals rely on touch, an especially powerful form of nonverbal communication.

We must distinguish between vocal and verbal aspects. Verbal and nonverbal communication includes both vocal and nonvocal elements.

A vocal element of verbal communication is spoken words — for example, saying, “Come back here.” Paralanguage is a vocal element of nonverbal communication, which is the vocalized but not verbal part of a spoken message, such as speaking rate, volume, and pitch. Nonvocal elements of verbal communication include using unspoken symbols to convey meaning. Writing and American Sign Language (ASL) are nonvocal examples of verbal communication and are not considered nonverbal. Nonvocal communication elements include body language, gestures, facial expressions, and eye contact. Gestures are both nonvocal and nonverbal since most do not refer to a specific word like a written or signed symbol does. Relationships among vocal, nonvocal, verbal, and nonverbal aspects of communication are shown below (Hargie, 2011, p. 45).

Principles of Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication has a distinct history and separates evolutionary functions from verbal communication. For example, nonverbal communication is primarily biological, while verbal communication is primarily culturally based. This is evidenced by the fact that some nonverbal communication has the same meaning across cultures, while no verbal communication systems share the same universal recognizability (Andersen, 1999). Nonverbal communication evolved earlier than verbal communication, serving an essential survival function that helped humans later develop verbal communication. While some of our nonverbal communication abilities, such as our sense of smell, lost strength as our verbal capacities increased, other abilities, such as paralanguage and movement, have grown alongside verbal complexity.

Nonverbal Communication Conveys Important Interpersonal and Emotional Messages

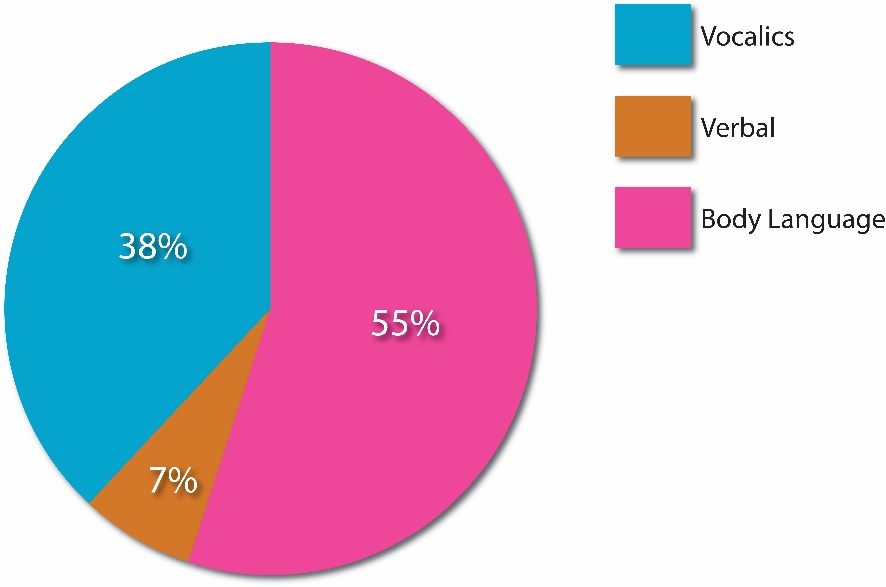

You have probably heard that more meaning is generated from nonverbal communication than from verbal. Mehrabian (1997) asserted that as much as 93% of meaning in any interaction is attributable to nonverbal communication. Of the three main elements of communication — vocalics (such as tone of voice), verbal (words), and body language — words account for only 7%. Regardless of the actual percentage, it is worth noting that the majority of meaning in interaction is deduced from nonverbal communication.

We may rely more on nonverbal signals when verbal and nonverbal messages conflict and when emotional or relational communication occurs (Hargie, 2011, p. 47). For example, when someone asks a question, unsure about the “angle” they are taking, we may hone in on nonverbal cues to fill in the meaning. The question “What are you doing tonight?” could mean many things: we rely on posture, tone of voice, and eye contact to see if the person asking is just curious, suspicious, or hinting that they would like company for the evening. We also put more weight on nonverbal communication when determining a person’s credibility. For example, if a health professional verbally speaks with a client, the content seems well-researched and unbiased. Still, if their nonverbal communication is poor (voice is monotone, avoids eye contact, fidgets), and the health professional will likely not be viewed as credible. Conversely, verbal communication might have more meaning in some situations than nonverbal communication. In interactions where information exchange is the focus — at a briefing at work, for example — verbal communication likely accounts for much more of the meaning generated. A fundamental principle of nonverbal communication is that it often takes on more meaning in interpersonal and emotional exchanges.

Nonverbal Communication is More Involuntary than Verbal

There are some instances in which we verbally communicate involuntarily. These types of exclamations are often verbal responses to a surprising stimulus. For example, we say “Oww!” when we stub our toe or scream “Stop!” when we see someone heading toward danger. Involuntary nonverbal signals are much more common. Although most nonverbal communication is not entirely involuntary, it is more below our consciousness than verbal communication and, therefore, more difficult to control.

This involuntary nature of nonverbal communication makes it more difficult to control or “fake.” For example, although you can consciously smile and shake hands with someone when you first see them, it is difficult to fake that you are “happy” to meet someone. Nonverbal communication leaks out in ways that expose our underlying thoughts or feelings. Health professionals and students in health studies must learn to control their facial expressions and other nonverbal communication to effectively convey their message without having their thoughts and feelings leak through.

Have you ever tried to conceal your surprise, suppress your anger, or act joyful even when you were not? Most people whose careers do not involve conscious manipulation of nonverbal signals find controlling or suppressing them challenging. While we can consciously decide to stop sending verbal messages, our nonverbal communication always has the potential to generate meaning for another person. The teenager who decides to shut out his dad and not verbally communicate with him still sends a message with his “blank” stare (still a facial expression) and lack of movement (still a gesture). In this sense, nonverbal communication is “irrepressible” (Andersen, 1999).

Nonverbal Communication is More Ambiguous

Language’s symbolic and abstract nature can lead to misunderstandings, but nonverbal communication is even more ambiguous. As with verbal communication, most of our nonverbal signals can be linked to multiple meanings, but unlike words, many nonverbal signals do not have one specific meaning. If you have ever had someone wink at you and did not know why you have probably experienced this uncertainty. Did they wink to express their affection for you, their pleasure with something you just did, or because you share some inside knowledge or joke?

Just as we look at context clues in a sentence or paragraph to derive meaning from a particular word, we can look for context clues in various sources of information, such as the physical environment, other nonverbal signals, or verbal communication to make sense of a particular nonverbal cue. Unlike verbal communication, nonverbal communication does not have explicit rules of grammar that bring structure, order, and agreed-upon usage patterns. Instead, we implicitly learn norms of nonverbal communication, which leads to more significant variance. In general, we exhibit more idiosyncrasies in our usage of nonverbal communication than in verbal communication, which also increases the ambiguity of nonverbal communication.

Nonverbal Communication is More Credible

Although we can rely on verbal communication to fill in the blanks sometimes left by nonverbal expressions, we often put more trust into what people do over what they say. This is especially true in times of stress or danger when our behaviour becomes more instinctual, and we rely on older systems of thinking and acting that evolved before our ability to speak and write (Andersen, 1999). This innateness creates intuitive feelings about the genuineness of nonverbal communication, and this genuineness relates to our earlier discussion about the sometimes involuntary and often subconscious nature of nonverbal communication. An example of the innateness of nonverbal signals can be found in children who have been blind since birth but still exhibit the same facial expressions as sighted children. In short, nonverbal communication’s involuntary or subconscious nature makes it less easy to fake, making it seem more honest and credible.

Functions of Nonverbal Communication

A primary function of nonverbal communication is to convey meaning by reinforcing, substituting for, or contradicting verbal communication. Nonverbal communication is also used to influence others and regulate conversational flow. Perhaps even more important are how nonverbal communication functions as a central part of relational communication and identity expression.

Nonverbal Communication Conveys Meaning

As we have established, nonverbal communication plays an important role in communicating successfully and effectively and cannot be underestimated.

Complementing

Complementing is defined as nonverbal behaviour combined with the verbal portion of a message to emphasize the meaning of the entire message. Regarding complementing verbal communication, gestures can help describe a space or shape that another person is unfamiliar with in ways that words alone cannot. Gestures also reinforce basic meaning — pointing to the door when you tell someone to leave. Facial expressions reinforce the emotional states we convey through verbal communication (Hargie, 2011, p. 46); smiling while telling a funny story better conveys your emotions. Vocal variation can help us emphasize a particular part of a message, which helps reinforce a word or sentence’s meaning. For example, “How was your weekend?” conveys a different meaning than “How was your weekend?” An excellent example of complementing behaviour is when a child exclaims, “I’m so excited,” while jumping up and down. The child’s body further emphasizes, “I’m so excited.”

Contradicting

At times, an individual’s nonverbal communication contradicts their verbal communication. Because we often perceive nonverbal communication as more credible than verbal communication, this is especially true when we receive mixed messages or messages in which verbal and nonverbal signals contradict each other. For example, a person may say, “You cannot do anything right!” in a mean tone but follow that up with a wink, which could indicate the person is teasing or joking, or a person could say, “I am fine” in a quick, short tone that indicates otherwise. Mixed messages lead to uncertainty and confusion for the receivers, which leads us to look for more information to determine which message is more credible. If we cannot resolve the discrepancy, we will likely react negatively and potentially withdraw from the interaction (Hargie, 2011, p. 52). Persistent mixed messages can lead to relational distress and hurt a person’s credibility in professional settings.

Accenting

Accenting is a form of nonverbal communication that emphasizes a word or a part of a message. The word or part of the message accented might change the meaning of the message. Accenting can be accomplished through multiple types of nonverbal behaviour. Gestures paired with a word can provide emphasis, such as when an individual says, “No (slams hand on table), you do not understand me.” By slamming the hand on a table while saying “no,” the source draws attention to the word. Vocalic cues also allow us to emphasize particular parts of a message, which helps to determine the meaning (e.g., “She is my friend,” or “She is my friend,” or “She is my friend”). Additionally, words or phrases can also be emphasized via pauses. Speakers will often pause before saying something important. Your professors likely pause just before relaying important information to the course content.

Repeating

Nonverbal communication that repeats the meaning of verbal communication assists the receiver by reinforcing the sender’s words. Nonverbal communication that repeats verbal communication may stand alone, but when paired with verbal communication, it repeats the message. For example, nodding one’s head while saying “yes” reinforces the meaning of the word “yes,” and the word “yes” reinforces the head nod, or saying “I am not sure” with an uncertain tone.

Regulating Conversational Flow

Conversational interaction has been likened to a dance, where each person has to make moves and take turns without stepping on the other’s toes. Nonverbal communication helps us regulate our conversations so we do not constantly interrupt each other or wait in awkward silence between speaker turns. Pitch, a part of vocalics, helps cue others into our conversational intentions. A rising pitch typically indicates a question and a falling pitch indicates the end of a thought or the end of a conversational turn. We can also use a falling pitch to indicate closure, which can be very useful at the end of a speech to signal to the audience that you are finished, which cues the applause and prevents an awkward silence that the speaker ends up filling with “That’s it” or “Thank you.”

Other behaviours that regulate conversational flow are eye contact, moving or leaning forward, changing posture, and eyebrow raises, to name a few. You may also have noticed several nonverbal behaviours people engage in when trying to exit a conversation. These might include stepping away from the speaker, checking one’s watch or phone for the time, or packing up belongings. These are referred to as leave-taking behaviours. Without the regulating function of nonverbal behaviours, it would be necessary to interrupt conversational content to insert phrases such as “I have to leave.” Repeating a hand gesture or using one or more verbal fillers can extend our turn even though we are not verbally communicating. We can “hold the floor” with nonverbal signals even when we are unsure what to say next. However, verbal communication will be used instead when interactants fail to recognize regulating behaviour.

Substituting

Nonverbal communication can substitute for verbal communication in a variety of ways. Nonverbal communication can convey much meaning when verbal communication is ineffective because of language barriers. Language barriers exist when a person has not yet learned to speak or loses the ability to speak. For example, babies who have not yet developed language skills make facial expressions at a few months old that are similar to those of adults and, therefore, can generate meaning (Oster et al., 1992). People who have developed language skills but cannot use them because they have temporarily or permanently lost them or are using incompatible language codes, as in some cross-cultural encounters, can still communicate nonverbally. Although it is always a good idea to learn some of the languages of a client who may not speak the same language as you, gestures such as pointing or demonstrating the size or shape of something may suffice in fundamental interactions.

Nonverbal communication is also helpful in a quiet situation where verbal communication is disturbing; for example, you may gesture to signal to your professor that you are ready to leave the classroom. Crowded or loud places can impede verbal communication and lead people to rely more on nonverbal messages. Getting a server or bartender’s attention with a hand gesture is more polite than yelling, “Hey you!” Finally, sometimes we know it is better not to say something aloud. If you want to point out a person’s unusual outfit or signal to a friend that you think his or her date is incompatible, you are probably likelier to do that nonverbally.

Influencing Others

Nonverbal communication can be used to influence people in a variety of ways, but the most common way is through deception. Deception is typically thought of as the intentional act of altering information to influence another person, which extends beyond lying to include concealing, omitting or exaggerating information. At the same time, verbal communication is to blame for the content of the deception; nonverbal communication partners with language in deceptive acts to make them more convincing. Since most intuitively believe that nonverbal communication is more credible than verbal communication, we often intentionally try to control our nonverbal communication when using deception. Likewise, we evaluate other people’s nonverbal communication to determine the veracity of their messages. Students initially seem surprised when we discuss the prevalence of deception, but their surprise diminishes once they realize that deception is not invariably malevolent, mean, or hurtful. Deception has negative connotations, but people use deception for many reasons, including to excuse their mistakes, be polite to others, or influence others’ behaviours or perceptions.

The fact that deception served a crucial evolutionary purpose helps explain its prevalence among humans today. Species that are capable of deception have a higher survival rate. Other animals engage in nonverbal deception that helps them attract mates, hide from predators, and trap prey (Andersen, 1999). To put it bluntly, the better at deception a creature is, the more likely it is to survive. So, over time, the humans who were better liars were the ones whose genes were passed on. However, the fact that lying played a part in our survival as a species does not give us a license to lie.

Aside from deception, we can use nonverbal communication to “take the edge off” a critical or unpleasant message to influence the other person’s reaction. We can also use eye contact and proximity to get someone to move or leave an area. For example, hungry diners waiting to snag a first-come-first-serve table in a crowded restaurant send messages to the people who have already eaten and paid that it is time to go. People on competitive reality television shows such as Survivor and Big Brother play what they call a “social game.” The social aspects of the game involve the manipulation of verbal and nonverbal cues to send strategic messages about oneself in an attempt to influence others. Nonverbal cues such as the length of a conversational turn, volume, posture, touch, eye contact, and choices of clothing and accessories can become part of a player’s social game strategy. Although reality television is not a reflection of real life, in real life, people do engage in competition and strategically change their communication to influence others, making it essential to be aware of how we nonverbally influence others and how they may try to influence us.

Affecting Relationships

To successfully relate to others personally and professionally, we must possess some skill at encoding and decoding nonverbal communication. The nonverbal messages we send and receive influence our relationships positively and negatively and can work to bring people together or push them apart. Nonverbal communication in the form of tie signs, immediacy behaviours, and expressions of emotion are just three examples illustrating how nonverbal communication affects our relationships.

Tie signs are nonverbal cues that communicate intimacy and signal the connection between two people. These relational indicators can be objects like wedding rings or tattoos that symbolize another person or the relationship, actions like sharing the same drinking glass or touch behaviours such as handholding (Afifi & Johnson, 2005, p. 190). Touch behaviours are the most frequently studied tie signs and can communicate much about a relationship based on the area being touched, the length of time, and the intensity of the touch. Kisses and hugs, for example, are considered tie signs, but a kiss on the cheek is different from a kiss on the mouth, and a full embrace is different from a half embrace. If you consider yourself a “people watcher,” note the various tie signs you see people use and what they might say about the relationship.

Immediacy behaviours play a central role in bringing people together and have been identified by some scholars as the most crucial function of nonverbal communication (Andersen & Andersen, 2005). Immediacy behaviours are verbal and nonverbal behaviours that lessen the real or perceived physical and psychological distance between communicators and include things such as smiling, nodding, making eye contact, and occasionally engaging in social, polite, or professional touch (Comadena et al., 2007). Immediacy behaviours are a good way of creating rapport or a friendly and positive connection between people. Skilled nonverbal communicators are more likely to create rapport with others due to attention-getting expressiveness, warm initial greetings, and an ability to get “in tune” with others, which conveys empathy (Riggio, 1992, p. 12). These skills are essential to help initiate and maintain relationships.

While verbal communication is our primary tool for solving problems and providing detailed instructions, nonverbal communication is our primary tool for communicating emotions. Touch and facial expression are two primary ways we express emotions non-verbally. Love is a primary emotion we express nonverbally and forms the basis of our close relationships. Although no single facial expression for love has been identified, it is expressed through prolonged eye contact, close interpersonal distances, increased touch, and increased time spent together, among other things. Given many people’s limited emotional vocabulary, nonverbal expressions of emotion are central to our relationships.

Expressing Our Identities

Nonverbal communication expresses who we are. Our identities (the groups to which we belong, our cultures, our hobbies and interests, and so on) are conveyed nonverbally through the way we set up our living and working spaces, the clothes we wear, the way we carry ourselves, and the accents and tones of our voices. Our physical bodies give other impressions about who we are; some of these features are more under our control than others. Height, for example, has been shown to influence how people are treated and perceived in various contexts. Our level of attractiveness also influences our identities and how people perceive us. Although we can temporarily alter our height or looks — for example, with different shoes or coloured contact lenses—we can only permanently alter these features using more invasive and costly measures such as cosmetic surgery. We have more control over other aspects of nonverbal communication regarding how we communicate our identities. For example, the way we carry and present ourselves through posture, eye contact, and tone of voice can be altered to present ourselves as warm or distant, depending on the context.

Aside from our physical body, artifacts, the objects and possessions surrounding us also communicate our identities. Examples of artifacts include our clothes, jewelry, and space decorations. In all the previous examples, implicit norms or explicit rules can affect how we nonverbally present ourselves. For example, in a particular workplace, it may be a norm (implicit) for people in management positions to dress casually, or it may be a rule (explicit) that different levels of employees wear different uniforms or follow particular dress codes. We can also use nonverbal communication to express identity characteristics that do not match up with who we think we are. Through changes to nonverbal signals, a capable person can try to appear helpless, a guilty person can try to appear innocent, or an uninformed person can try to appear credible.

Activity: Check Your Understanding

Key Takeaways

- Nonverbal communication is a process of generating meaning using behaviour other than words. Nonverbal communication includes vocal elements, referred to as paralanguage and pitch, volume, and rate, and nonvocal elements, usually referred to as body language, including gestures, facial expressions, and eye contact, among other things.

- Nonverbal communication serves several functions: Nonverbal communication affects verbal communication in that it can complement, substitute, contradict, accentuate, repeat, and regulate.

- Nonverbal communication regulates the conversational flow, providing essential cues that signal the beginning and end of conversational turns and facilitate the beginning and end of an interaction.

- Nonverbal communication affects relationships, as it is a primary means through which we communicate emotions, establish social bonds, and engage in relational maintenance.

- Nonverbal communication expresses our identities, as who we are is conveyed through how we set up our living and working spaces, the clothes we wear, our presentation, and the tones in our voices.

Exercises

- To better understand nonverbal communication, imagine an example to illustrate each of the principles discussed in the chapter. Be integrative by including at least one example from an academic, professional, and personal context.

- When someone sends you a mixed message in which the verbal and nonverbal messages contradict each other, which one do you place more meaning on? Why?

- Our professional presentation, dress style, and surroundings, such as an office, clinic, or hospital environment, send nonverbal messages about our identities. Analyze some of the nonverbal signals that your professional presentation or environment sends. What do they say about who you are? Do they create the impression that you desire?

References

Afifi, W. A., & Johnson, M. L. (2005). The nature and function of tie-signs. In V. Manusov (Ed.), The sourcebook of nonverbal measures: Going beyond words (pp. 189–198). Erlbaum.

Andersen, P. A. (1999). Nonverbal communication: Forms and functions. Mayfield.

Andersen, P. A., & Andersen, J. F. (2005). Measures of perceived nonverbal immediacy. In V. Manusov (Ed.), The sourcebook of nonverbal measures: Going beyond words (pp. 113–126). Erlbaum.

Comadena, M. E., Hunt, S. K., & Simonds, C. J. (2007). The effects of teacher clarity, nonverbal immediacy, and caring on student motivation, affective and cognitive learning. Communication Research Reports, 24(3), 241–248. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08824090701446617

Hargie, O. (2011). Skilled interpersonal interaction: Research, theory, and practice (5th ed.). Routledge.

Oster, H., Hegley, D., & Nagel, L. (1992). Adult judgments and fine-grained analysis of infant facial expressions: Testing the validity of a priori coding formulas. Developmental Psychology, 28(6), 1115–1131. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1115

Riggio, R. E. (1992). Social interaction skills and nonverbal behavior. In R. S. Feldman (Ed.), Applications of nonverbal behavioral theories and research. Erlbaum.

Image Attributions

Figure 4.1.1. Mehrabian, A. (1971). Silent messages. Wadsworth.

Attribution Statement

Content adapted, with editorial changes, from:

University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. (2013). Communication in the real world [Adapted]. https://open.lib.umn.edu/communication/

Wrench, J. S., Punyanunt-Carter, N., & Thweatt, K. S. (n.d.). Interpersonal communication: A mindful approach to relationships. Milne Library Publishing.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.