1.5 Tips for Studying

It is hard to come up with a prescribed method of studying that will work for all students. Most seasoned students will tell you that they figured out what works for them through trial and error, so while it is good to start with a plan based on what you think will work for you, the strategies you start your semester with may need some tweaking as you go along, and different courses may require different approaches.

To recall specific types of information on an exam, such as the names and definitions of key theories or concepts, significant dates, or important people and events, we work to transfer that information from our short-term memories into our long-term memories, plus we have to get used to recalling that information when we need it.

Our long-term memories store information best when it is meaningful to us, when we can recognize why it is important, when we have encountered the information many times, and when we can link it to other information that we know. For these reasons, the reading and notetaking methods discussed in this chapter focus so heavily on establishing context, reviewing information regularly, and drawing connections to other information.

Recall strategies help us learn to retrieve information on demand. Have you ever been in an exam and you know that you know an answer to a question, but it does not pop into your head until long after you have left the exam, maybe when you are doing dishes or brushing your teeth that evening? You might think there is something wrong with your memory, but in fact, the information was there all along. The problem is being able to recall it in the moment that you require it. The following strategies can help:

Cover Your text or Notes and Review Margin Notes

Previously in this chapter, you learned about using the margins of your textbook and notes to make notations to yourself that you could use to test yourself later. This is a powerful recall tool that works the same way as flashcards, but it can save you a lot of time. As you look at your brief notations in your margin (e.g. deviance definition, three factors, three paradigms), recall the answers yourself before looking at your notes or textbook to confirm your answers.

Make Flashcards

If you prefer using index cards because you feel like the process of making them helps you and you appreciate their portability, that is fine too. Be mindful of what information you put on your flashcards, though. Remember, these are best for concepts, definitions, people, events, timelines, and places, but you will want to use other strategies to process complex connections or critical responses. If you want, you can check out some of the flashcard apps available for your mobile device, or you can use index or recipe cards available in most stationery stores.

Create Fill-in-the-Blank Charts or Diagrams

In cases where you need to remember several interconnected or similar pieces of information, try making a blank chart or diagram that you can make several copies of and fill in the blanks to help you remember. For example, if you are in a political science course about the Canadian government, and you are asked to remember the core institutions responsible for governing Canada and their relationship to one another, you can create a chart that shows their hierarchical relationships to one another to help you visualize how they work together, and you can test your knowledge by filling in blank versions of the chart with the appropriate governing bodies.

Practice Elaborative Rehearsal

Practice elaborative rehearsal rather than verbatim memorization, otherwise known as rote learning. Rote learning is fine when you have a limited number of things to memorize, such as a phone number, a locker combination, or a couple of basic formulas, but it is ineffective when we have lots of information to remember, as in the case of studying several textbook chapters for an exam, or when we are expected to exercise critical thinking or interpretation for long answer items, as is the case in many social sciences courses. Elaborative rehearsal means that you put your energy into understanding the meanings of terms and concepts rather than trying to memorize their textbook definitions word-for-word. Instead of trying to repeat the exact wording over and over, try to paraphrase the information by putting it into your own words, as if you are teaching it to someone else. Go ahead and say it out loud!

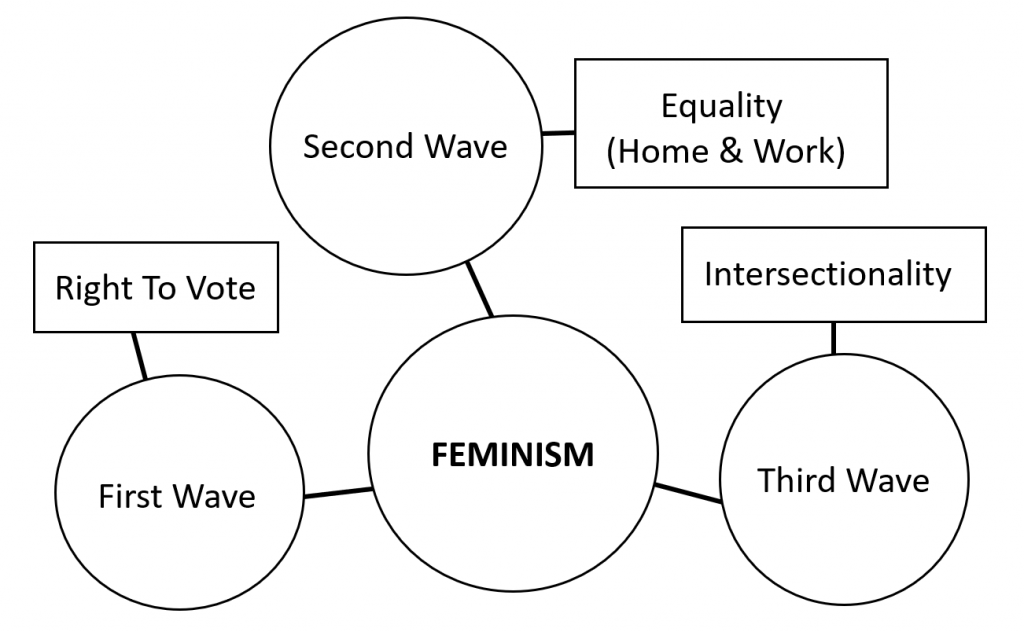

Concept Mapping

Concept mapping is especially helpful for developing an understanding of how large or complex pieces of information fit together. Historical timelines are a good example of concept mapping that can help us easily see the sequence of key events, but these are not just useful in history courses. They can also be applied in sociology, political science, psychology, English, or other courses to help link key concepts and to see how different people and events influenced each other or how several theoretical perspectives and developments came out of one main perspective (as an example, see Figure 1).

Study Buddies or Study Groups

Discussing information with others is a highly effective way of remembering it and of deepening our understanding of a topic. When we have a conversation about something, we are often given lots of other memorable information to attach to it. Someone will tell a story, or they will share their own methods of remembering that information, or they will talk about how it relates to something they have learned in another class. These forms of sharing ideas aid in the recall of information because they provide additional meaning and context for us to latch onto. They also allow us to practice sharing our interpretation of course material while getting feedback from others who might let us know when we have really explained something well or if we are maybe a little off track.

The trick with study groups is that you want to make sure that everyone is participating, and you need to form a group with trusted peers who you know are going to stay on track. If only one person is doing all the talking and everyone else is listening, that one person is getting most of the benefit because they are the ones paraphrasing and teaching the information to everyone else.

If you do not have any peers you feel comfortable studying with, that is okay too. It is still beneficial to try to discuss and explain concepts with others, even if they are not in the course, or to your dog, cat, or goldfish, or even just to yourself. One of the authors prepared for most of her undergraduate essays and exams by going for long walks to think about how she would explain her ideas to someone else.

Using Supplemental Information

Supplemental information is information that may not be part of your assigned readings but that can be used to help you better remember, understand, or apply key concepts. Here are some examples of supplemental information you might use.

Websites Accompanying Textbooks

Publishers frequently create websites you can access to supplement the information published in textbooks. These sites may be completely free, or your textbook may come with an access code that you can use to sign in and create an account. These sites often have additional examples, practice questions, videos or interactive learning tools that present the information in a different way.

Case Studies or Examples

Often, students make the mistake of skipping over the case studies or lengthy examples provided in their textbooks, but these sections can go a long way in helping you see how the information is applied to real-world contexts or helping you remember a concept by connecting it to a story or event.

Recommended Readings

Some professors recommend readings in addition to those that are required for a course lecture. Think of these readings as helpful suggestions for if you are particularly interested in a topic and want to know more, perhaps so you can pursue it as an essay topic, or if you are still uncertain about the topic and need a little extra help wrapping your head around it.

Additional Web Resources

Especially with free online educational content (otherwise known as open educational resources) gaining momentum, there is lots of good, free information online about many university-level subjects. You might find study guides or lecture notes that other professors have put online, or you might find free online lectures or courses through sites like:

- Khan Academy (https://www.khanacademy.org)

- MIT Open Courseware (https://ocw.mit.edu)

- Open Yale Courses (https://oyc.yale.edu)

These are especially helpful if you want concepts or key ideas explained in a different way or in more detail to help you understand them better. And do not rule out podcasts and videos either! Sometimes these resources can help us reflect on main ideas through a different lens or draw unlikely connections we would not have otherwise thought of. If you are not sure where to start or if something looks trustworthy, your professor or a librarian can help.