Alberta Infodemic? A Study of COVID-19 Crisis Communications in Alberta (full article)

Elka Eisenzimmer, Michelle Huley, Sahana Walji

Abstract

The main themes of vaccine hesitancy identified in a growing body of scholarship include freedom and mistrust in government and institutions, and critique of government handling of the pandemic. Social media is a prevalent source of information in developing attitudes and subsequent behaviours, but government messaging continues to be the most trusted source in a public health crisis. However, vaccine acceptance depends on the government adapting to the fast-changing and increasing influence of social media on the public’s attitudes and behaviours. This research studies the messaging of and public response to government communications which informs attitudes, barriers, compliance, and patterns of denialism and vaccine hesitation. This study sought to determine if a Covid-19 infodemic contributed to the current health crisis in Alberta by amplifying inconsistent messaging disseminated by provincial officials. The methodology includes collecting and analyzing messaging from six Government of Alberta Covid-19 update videos, corresponding reciprocal comments on social media, and em qualitative analysis of relevant academic material. Together, these aspects help frame and inform the need for a clear, consistent, integrated government response, and how messaging has the power to influence, possibly contributing to a fourth wave of Covid-19 in Alberta. Vaccine hesitancy, misinformation, and denialism are prevailing themes on social media, but could early, effective government response have staved off Alberta’s fourth wave of Covid-19? Conclusions from data collected are a valuable contribution to the growing body of literature surrounding effective pandemic and crisis messaging. This research did not provide conclusive results to indicate whether official messaging contributed to an infodemic. Further study of Alberta’s crisis communications during this pandemic would be a valuable addition to the literature and would help inform future crisis communications.

Keywords: Misinformation, sensemaking, messaging, crisis communication, infodemic

Introduction

Alberta declared two public health emergencies on September 15, 2021 (Alberta Government, Orders in Council, 2021) and on March 17, 2021 (Alberta Government, Orders in Council, 2021), due to increasing numbers of Covid-19 infections. There were 20, 917 cases on March 17 (YourAlberta, 2021, March 17), which caused concern for the viability of province-wide intensive care units, particularly among unvaccinated or partially vaccinated individuals.

Public response to the Covid-19 pandemic in Alberta has been varied, with an unusually high number of people refusing vaccinations due largely to an expressed distrust of government and institutions. This mixed method study focuses on the institutional messaging from the province of Alberta and the reactionary misinformation expressed on social media platforms in response to government pandemic control measures, and broadly examines Alberta’s Covid-19 communication to determine how, or if, it contributed to an infodemic and subsequent vaccine hesitancy and resistance to pandemic-related public health measures.

When a public health emergency was declared due to increasing numbers of active cases, Alberta had more than twice as many cases as any other province (CBC, 2021). When this research was conducted, between September and December 2020, Albertans had experienced four “waves” of the pandemic, with lockdowns and reopenings intermittent. Public messaging from Alberta’s premier was inconsistent and seemed to prioritize the economy over the virus’ potential. Meanwhile, social media exploded with denialism, vaccine hesitancy, distrust of government, and extreme right-wing views expressed within a pandemic context. This research hypothesizes government messaging contributed to the expression of such views on social media, the subsequently reduced rate of vaccinations among Albertans, and protests against non-pharmaceutical measures intended to limit the spread of Covid-19. This research team sought insight to add to a growing body of literature about public health crisis communication. Although national communications regarding the Covid-19 pandemic are beyond the scope of this study, it should be noted that among the qualitative literature reviewed were many other examples of how government communications could have better managed the pandemic response, including that of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Has the Covid-19 infodemic contributed to the current health crisis in Alberta by amplifying inconsistent messaging disseminated by provincial officials?

Significance of the Study

Considerable research is available examining the impact of government and institution public health crisis communications that provide public information regarding Covid-19. Much of the Alberta government’s response to the pandemic, and measures implemented to inhibit the spread of Covid-19, are limited in effectiveness due to an infodemic which has contributed to denialism, anti-vaccination rhetoric, protests, and other social violence. Very little academic research specific to Alberta within this context is available. Understanding this phenomenon during the Covid-19 pandemic in Alberta provides context and informs public health crisis communications.

Limitations

There are several limits to this study. Secondary research specific to Alberta is very limited, as is that pertaining to Canada. This study will therefore utilize a breadth of academic research pertinent to Alberta, Canada, and other countries. A review of the more than 240 Government of Alberta Covid-19 update videos is beyond the scope of this study, as is coding and analysis of the entirety of social media comments and unique interactions available on this topic. The data supporting this research was collected from September to December 2020, and subsequent information was therefore not included in this study but is pertinent and further study and data collection could be potentially informative in framing public health crisis discourse. Social media comments are also moderated, which limits access to content that has been filtered for abusive or misleading subject matter. It was not possible, due to this study’s scope, to identify content delivered by bots. Social media platforms evaluated in this study have been limited to Facebook due to limited scope. It should be noted one member of the research team previously worked for an NDP Member of the legislative assembly in an administrative capacity and chaired the candidate’s 2019 provincial election campaign as a volunteer. This was a historical position, and any potential bias is noted. Division of research responsibilities mitigated any bias in research.

Definition of Terms

Infodemic: An infodemic is too much information including false or misleading information in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak (World Health Organization, n.d., para. 1).

Social network analysis: A research method developed primarily in sociology and communication science, focuses on patterns of relations among people and groups such as organizations and states. As the Web connects people and organizations, it can host social networks. Therefore, social network analysis has been used to study Web hyperlinks (Hansen & Himelboim, 2020).

Unique interaction: On social media, this is original content that has been posted for the first time on social media, this does not include “retweets”, “shares”, or “likes.” A unique post or interaction can include a reply to a post, an original comment, or a reshare or retweet that has been posted with additional commentary or information (Walji, 2021).

Summary

Alberta has been in the midst of a fourth wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, with hospitaladmissions steadily increasing and ICU capacities strained beyond any previously knownoccurrences. Alberta’s Premier Jason Kenney declared the pandemic over and Alberta open forthe greatest summer ever on July 1, 2021 (YourAlberta, May 26, 2021), just a couple of shortmonths before being forced to declare a public health emergency on Sept. 15 (alberta.ca, 2021), due to the increasingly persistent and mounting evidence that Alberta is still in crisis. Vaccinehesitancy, and distrust in government and institutions, is an apparent and a vocal aspect on socialmedia, with right-wing extremists also propagating fear online and in person at proteststhroughout Alberta. This study quantitatively examines how messaging from Alberta’s premiercontributed to Covid-19 denialism including vaccine hesitancy, how similar and differentleadership styles led to similar or dissimilar public measures and containment of the virus’spread, and what role the vocal minority has played in perpetuating such denialism on social media. This research adds to an increasing body of literature examining social, political, andpublic health communications in a public health crisis and informs emerging communicationsstrategies that are intended to mitigate provincial, national, and global impacts of a public healthcrisis.

Review of the Literature

Introduction

Governmental and official institutional communication is a trusted source of information utilized by the public for crises such as Covid-19. Research shows this is Canadians’ most trusted source of information about the pandemic and measures the government and public health officials are taking and contributes to increased compliance with public health measures. But it can also contribute to negative attitudes and behaviours including vaccine hesitancy when mistrust in institutional messaging is inherent. The use of social media as a significant source of information is an epistemological and historical shift in crisis communication, which can be used effectively to disseminate institutional messaging but can also substantially contribute to behaviours such as vaccine hesitancy and attitudes of mistrust. The literature reviewed examines government messaging from a variety of perspectives encompassing sociological, psychological, and anthropological studies of how such messaging is relayed and received, while other source materials provide context with historical response to a public health crisis in Canada, and the current trends and attitudes being expressed on social media platforms.

Moral Panic Frames Pandemic Response

Establishing trust is vital to public health crisis communications. In examining Canadian pre-crisis risk communication through a framework of moral panic, in which the concept of implicatory denial is analyzed, Hier (2021) concludes that Canadian pre-crisis Covid-19 communication was lacking in cohesion, contradictory across multidimensional jurisdictions, and ultimately led to a broader public discourse of denial (p. 506) that “… failed to proportionately translate available knowledge of risk into the most effective and timely mitigation strategies” (p. 517). Hier (2021) examines the underreaction of government pre-crisis risk communication in the three months leading up to the pandemic’s acute phase, as a “form of implicatory denial” (p. 506), connecting infectious disease crisis communication to the “social, economic and political implications of underreacting to real-world threats” (p. 505).

The study of moral panic, states Hier (2021), is focused on agency that is characterized in debate. He describes three areas of needed study he utilizes to study Canadian political reactions and messaging in the first wave of the Covid-19 pandemic: denial theory; social, economic, and political implications of disproportionate reactions to this real-world threat; and infectious disease crisis communication (p. 506).

Hier (2021) explains that pre-crisis risk communications are the official narratives communicated by officials to make sense of rapidly emerging diseases, and usually presented as “standardized claims about risk assessment, risk preparedness, and crisis planning” (p. 508). He (2021) notes uncertainty of Covid-19 crisis communications in Canada, specifically the official narratives that sought to reassure the public of a low likelihood of widespread infection, reiterated that Canadian leaders were in control, and attempted to proactively prevent panic, effectively contributing to the inability of Canadian and provincial authorities to act pre-emptively and collectively. “Instead (the dynamics of denial) manifested in the form of poor communication, mixed messaging, and contradiction across multi-jurisdictional claims-making domains” (p. 508).

In a qualitative analysis of news stories, health releases, speeches, and official briefings, the author considers the shifting and mixed messages that rhetorically illustrated hesitation of federal and provincial authorities in three phases of the first three months of the pandemic: January 1–25, 2020; Under-acknowledgement, January 26–March 4, 2020; Escalation and Reassurance, and March 5–31, 2020; Mixed Messaging and Contradiction. Through a narrative timeline, Hier (2021) analyzes the content of federal and selected provincial messages beginning in January 2020 and identifies Canadian health officials’ underestimation of the significance of the risks raised by the novel coronavirus. The communications of Canada’s Health Minister Patty Hadju, Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam, and British Columbia provincial health officer Bonnie Henry were examined. Hier determined all three reacted to quickly changing information about community transmission with inadequate travel restrictions while defending the efficacy with repeated reassurances that the risk of infection was low, and that the government was in control of the situation (pp. 509–510). ‘Escalation and reassurance’ of phase 2 began after Canada’s first presumptive case of Covid-19 was confirmed on January 26. Several cases had already been confirmed in the U.S (Hier, 2021, pp. 510–512).

Tam, and other public health officials, continued to downplay the risks of Covid-19,instead problematizing misinformation, with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau defending Canada’sstill-open border as late as March 5 (Hier, 2021, p. 510). The first Covid-19 related death onMarch 9, in British Columbia’s Lynn Valley Care Centre, marked the beginning of the thirdphase identified by Hier, Mixed Messaging and Contradiction (Hier, 2021, pp. 512–516). TheWorld Health Organization declared a pandemic on March 11. Canada had 100 confirmed cases.Subsequent messaging became confusing, particularly among provincial officials and a range ofcontradictory messages across the country, as health officials downplayed the risk of infection bydiscouraging border closures and travel bans. The Canadian media began calling for moreaggressive action. When the Canada-U.S. border was closed to non-essential travel on March 21,there were 1,330 confirmed and presumptive infections across Canada. The quarantine ofpassengers from the Grand Princess Hawaiian cruise ship contradicted the return of passengers atCanadian airports, from some of the worst-affected regions of the world, with little or noscreening. Such contradictions “…in the absence of national and provincialresponses created confusion, exacerbated mixed messaging, and threatened to undermine trust inpublic health claims making” (Hier, 2021, p. 514).

By socially constructing risk conditions through emotional, psychological, social, cultural,and normative claims and frames, as much as they rationally and scientifically responded to theobjective dimensions of viral behaviour, Canadian and provincial public health claims makersdisproportionately translated available knowledge of risk into the most effective and timelymitigation strategies. Hier’s research highlights the need for cohesion and cooperation in pre-riskcrisis communications among national and subnational (provincial) governments. Hier describesthree types of content denial: literal, interpretive, and implicatory denial. All three may promptinvestigation from a standpoint that harm has been done, connects this current research, andframe Covid-19 messaging from Alberta’s premier and CMOH, specifically the “rhetoricaldeflection, strategic framing, and political spin” (Hier, 2021, p. 508) utilized by provincial officials intheir rationalizing and repackaging of Alberta Covid-19 measures in implicatory denial. Verylittle research has been conducted on subnational or provincial communication strategies utilizedto convey risks and preventative measures during Covid-19, but the opportunity to study suchmessaging as the pandemic continues, with Alberta’s health system on the verge of collapse, is anopportunity to proactively inform future strategy.

Alberta Social Media Data Correlated to Covid

A great deal of recent academic literature and research has focused on patterns of debate on social media, and most recently, the narratives which have contributed to Covid-19 denialism and vaccine hesitancy. Boucher et al. (2021) use social network analysis and unsupervised machine learning in this infodemiology study to globally characterize Tweets about vaccine hesitancy, evaluating attitudes and behaviours that contribute to Covid-19 vaccine hesitancy. This data-driven study’s objective is to “evaluate societal attitudes, communication trends, and barriers to Covid-19 vaccine uptake through social media content analysis to inform communication strategies promoting vaccine acceptance (Boucher et al., 2021, p. 1) and puts into context how government communication can inform behaviours and facilitate behavioural change.

This study examines the attitudes on vaccines that are driven by social media, specifically Facebook, to better understand the “current patterns of communication that characterize the immunization debate on social media platforms” (p. 2). They hypothesize this data to be of global importance in developing targeted Covid-19 vaccine communication and intervention strategies on Twitter (p. 3). The authors intend to provide data that will inform successful public messaging for improved Covid-19 vaccine uptake. They emphasize “Rather than just trying to enhance knowledge, a different approach to overcoming vaccine hesitancy for Covid-19 may be to focus on changing personal attitudes” (p. 2). To that end, this study provides data that can enable governments and institutions to devise targeted communication strategies that promote Covid-19 vaccine acceptance.

Boucher et al. (2021) collected tweets published in English and French between Nov. 19 and 26, 2020, just after the announcement of initial Covid-19 vaccine trials and used Social Network Analysis (SNA) to identify clusters expressing mistrust of the vaccine. Subsequent unsupervised machine learning was utilized to identify the main themes of vaccine hesitancy. The words “Covid” and “vacc” or “vax” or “immu” were collected through Twitter content and hashtags (p. 3). “In total, 636,516 tweets were collected from 428,535 accounts for an average of 79,564 tweets per day” (p.4), which found the largest cluster, 49.4%, connected to vaccine acceptance points of view, and 23.4% expressing vaccine hesitancy. 18.4% were English language Tweets originating mostly from the U.S., the U.K., and Canada and “gravitated around accounts of prominent anti-vaccine physicians and organizations, right wing activists … and some alternative news organizations” (p. 4). Further examination of the narratives embedded in this data provides insight into what drives vaccine-hesitant attitudes and includes vaccine safety and efficacy, mistrust of institutions, and concern for personal freedom. “A large percentage of such Tweets (31.2%) expressed some criticism of the government’s handling of the Covid-19 crisis, especially decisions to curb individual freedom” (p. 5). These results suggest trust in institutions is a key determinant of vaccine hesitancy (p. 5). Trust in government, which is mandated with vaccine development, approvals, and delivery, is critical to effective Covid-19 vaccination uptakes and management of the pandemic. Boucher et al. (2021) conclude the themes identified as being central to the vaccine-hesitant conversations on social media are driven by concerns around safety, efficacy, freedom, and mistrust in institutions (p. 8).

Building trust in institutions is vital to the creation of communication models that target vaccine hesitancy and have the potential to change attitudes and behaviours. This study frames attitudes around the hesitancy debate and underlines the drivers of such conversations, which informs our research as we examine how Alberta’s institutional messaging has contributed to vaccine hesitancy through an inadequate communication strategy. Social media narratives specific to Alberta align with the global attitudes investigated by Boucher et. al. These understandings are valuable to the creation of strategically informed public health communications with the potential to encourage increased vaccine uptake in Alberta, and successful management of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Leadership Approaches Frame Crisis Sensemaking

Covid-19 became global in 2020, with world leaders varying in their responses to the pandemic, “resulting in substantially different outcomes in terms of virus mitigation, population health, and economic stability” (Crayne & Medeiros, 2021, p. 462). Crayne and Medeiros provide a case study of three styles of leaders’ sensemaking in this public health crisis and elaborate on how those approaches were reflected in decision-making and crisis management (p. 462). The three cases are indicative of how leaders “of comparable influence, facing a universal crisis, can differ in their approach to making sense of the problem at hand” (p. 469).

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is studied as an example of a charismatic leadership approach; Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro provides an example of the ideological approach; and Germany’s Chancellor, Angela Merkel’s approach illustrates a pragmatic style (Crayne & Medeiros, 2021). The authors argue pragmatic leaders may be best equipped for managing crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic, and that the diverse approaches and outcomes exhibited in global responses highlight the need for better understanding of sensemaking in understanding and assessing potential leaders (p. 463).

Crayne and Medeiros describe sensemaking as a process by which individuals interpret cues about their changing environments, utilizing the interpretation to explain what occurred and consider future actions (Crayne & Medeiros, 2021, p. 463). In a crisis, sensemaking is a means to collect information, provide an explanation, and develop appropriate actions, and is an “essential element to successful navigation of crisis events” (Crayne & Medeiros, 2021, p. 463). The process provides a framework for the public to understand the crisis. Such interpretation of a leader’s communication underpins public motivation to comply with measures such as mask-wearing, social distancing, or vaccination (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 464).

The CIP leadership model, as described by Crayne and Medeiros, is viewed through the lens of sensemaking and sense-giving, and is comprised of three pathways: charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic, each of which is correlated to world views, “which impacts how leaders interpret and respond to events in their environment” (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 464). Charismatic leaders, as exemplified by the authors’ study of Trudeau, focus on positive emotions such as hope, and are framed within a vision for the future. “Trudeau’s largely charismatic approach has been consistent … and particularly evident in his approach to Canada’s Covid-19 response …” (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 465). Despite the positive messaging, however, Trudeau has been criticized for his approach to early detection and testing capacity, particularly among Canada’s most vulnerable populations, which has suggested unpreparedness (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 466).

The ideological leadership approach is one we have identified as the CIP approach most closely relating to the style of Alberta Premier Jason Kenney. This review expands the ideological framework rather than the charismatic and pragmatic pathways. According to Crayne and Medeiros (2021), the ideological style of leadership is one that adheres to previously established values and through adherence to tradition, with pathetic appeals to the values of followers and “implies the glory of the past can be reclaimed” (p. 467). This case study also notes the archetypal ideological leadership styles of former American presidents Ronald Regan and Donald Trump.

The past-focused vision of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, who has framed the Covid-19 pandemic in terms of “us-versus-them” is typical of an ideological leader. Some of his comments have been overwhelmingly negative, such as stating the virus was the result of media “hysteria” that was tricking citizens and exaggerating the “little flu” (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 467). Bolsonaro has consistently called for a return to normal, focusing on jobs and the Brazilian economy, which underscores his past focus and idealized perspective of Brazil’s past (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 467), and emphasizes the president’s prioritization of economic over public health actions as he contends “any downturns in the stock market were because of a misrepresentation of Covid-19 in the media” (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 467). The president’s denialism of Covid-19, advocacy for non-scientific ‘cures’ and the resulting delayed response to the pandemic has resulted in Brazil’s “careen[ing] toward a full-blown public health emergency and economic crisis” (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, p. 468). Such behaviours are indicative of ideological sensemaking outcomes, which include “tight adherence to values, demands of fealty, and dismissal of information and individuals that contravene the thematic narrative” (Crayne & Medeiros, 2021).

Based on the outcomes, including mass testing and lower Covid-19 related death rates, the study’s authors conclude the most effective leadership style in managing the pandemic is one illustrated by German Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose evidence-based response has been communicated with “rationality and appeals to scientific evidence” (Crayne & Medeiros, 2021, p. 468). They argue the pragmatic leader is the most effective problem solver and most able to lead in high stakes circumstances (p. 468) due to consistency in approach, and according to Mumford (2016), an “overwhelmingly problem-focused, rational approach to leadership” (p. 468). The authors state a “willingness and ability to seek expert advice, manage situational complexity, and balance differential goals,” are all distinguishing features of a pragmatic style of leadership (p. 469). Crayne and Medeiros caution, however, that there is no one size fits all to leadership or crisis management, with successful leadership also dependent on being able to effectively respond to challenges, and the fast-changing dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic potentially requiring different styles as needs also change over time.

Because our research qualitatively studies narrative messaging from Alberta’s Premier Jason Kenney, as the province was in the midst of a Covid-19 fourth wave with public health strained beyond capacity, case numbers and deaths steadily increasing, and younger people contracting and dying from the disease, this study is particularly pertinent. Identifying the leadership ideology that has contributed to a public health crisis in Alberta is vital information and provides a basis for future research into Albertans’ responses to the provincial response.

Lang et al. Drive Strategy with Data

The purpose of this research, which is the first phase of a multi-phase mixed methods approach, is to “inform data driven public health communication strategies, including knowledge translation tools, targeted marketing campaigns and community engagement to facilitate behaviour change” (Lang et. al., 2021, p. 2). The authors note support for public health measures is critical for reducing the virus’ spread, and understanding human behaviour is an integral aspect of informing “the public health response and communication strategies” (Lang et al., 2021, p. 2).

The authors explain previous research has identified variability in people’s willingness to accept a vaccine or support public health measures and include demographic factors (greater uptake is associated with females older than 50 and people with higher levels of education), expressing higher concern for Covid-19 and greater knowledge of the pandemic. They note emotions can drive response and risk perception perhaps even more than information: “We … sought to identify concerns regarding Covid-19 vaccinations and reasons why persons may or may not accept a vaccine” (p. 2).

This study was conducted through a cross-sectional online survey, created by the Alberta Health Services Primary Data Support Team, with targeted geographic areas of Calgary, Edmonton, and other urban and rural communities. Participants were selected through random phone calls from a purchased list of 3,000 and were then further filtered by criteria that would enable future focus group inclusion. Surveys were distributed by email and conducted through an online survey company, Acuity, with 60 people completing it. The main outcomes were focused on compliance with each of the public health measures, such as mask wearing, utilization of a contact tracing app, going to bars, pubs, and lounges, and staying home while sick (Lang et al., 2021, p. 3). Sociodemographic information was collected, and participants were categorized into a variety of factorial categories. Likert scales were used to compile data based on attitudes and beliefs from questions such as if participants believed public health recommendations reduce Covid-19 spread, how much these behaviours are influenced by people around them, if they’re important to reduce spread, and the level of difficulty of each behaviour. Sources of participants’ new information sources and their belief in the trustworthiness of information were also studied. Cluster analysis of news and social media consumption, and individual behaviour and concern level of Covid-19, provided the identity of key patterns, which were then analyzed (Lang et al., 2021, p. 3).

Results regarding vaccine hesitancy found that 41 (68%) persons would receive a Covid-19 vaccine if it were available, 12 (20%) would not, and 7 (12%) were unsure. Willingness to get a Covid-19 vaccine was less in other urban centers (29%) and rural Alberta (50%) compared to Calgary (75%) and Edmonton (80%). Of those with extreme concern for spreading the virus, 100% said they would receive a vaccine, compared to 44% who had no concern for spreading the virus (P = 0.006). Persons who reported they would accept a Covid-19 vaccine were also more likely to be compliant with public health measures including staying home when sick. Most participants expressed belief in the efficacy of health measures, while a significant proportion (25 to 30%) indicated they would be influenced by others’ compliance with health measures (Lang et. al., 2021, pp. 5–6).

Data gathered regarding trusted sources of Covid-19 information is particularly pertinent to this study as it provides context to the research. The majority of the study’s participants used Facebook™ (68%), followed by YouTube™ (58%) and Instagram™ (55%). Only 7% of respondents said that they used no social media. The majority of persons received their news from internet news sources (68%), however, 57% said they received their news on social media (Fig. 4), and 60% indicated social media to be among their most trusted sources for news and information about health. Alberta Chief Medical Officer of Health Deena Hinshaw’s media briefings were utilized by 60% of participants and trusted by 58%. The most trusted health information was that from physicians at 67%, however, only 27% reported they obtained their Covid-19 information from a physician (Lang et. al., 2021, pp. 6–8).

Cluster analysis, which identifies behaviours by attitudes, barriers, and information sources, is especially informative to this research and speaks to the need to adopt clear and consistent public health communication targeted at the groups most likely to resist compliance with measures: “believing that public health behaviours are effective is an important predictor of compliance within these behaviours” (Lang et al., 2021, p. 13).

Cluster analysis identified four clusters based on news and social media consumption and the relevant trust-related questions. Key insights included that “social media use as a news source was correlated with individuals’ reported tendency to be influenced by others in their health-related behaviours” (p. 7), and that “the reported trust level in health information on Covid-19

from health authorities was a key factor in distinguishing clusters” (p. 7). Other insights demonstrated by this survey were that the public health measure most followed and seen as having the most benefit in reducing Covid-19 spread is to stay home while sick. Use of a contact tracing app is seen as having the least benefit, is the most difficult to use/comply with, and least used, while persons living outside of Edmonton or Calgary felt masking in public is the most difficult of Covid-19 public health measures.

Lang et al. (2021) conclude effective public health interventions and targeted messaging intended to improve public trust, informed by an understanding of individuals’ attitudes, are vital elements to improving vaccine uptake and compliance with health measures. This information is particularly pertinent to this research, especially as the data collected is specific to Alberta: it identifies the trends, patterns, and behaviours that can be prohibiting compliance with public health measures, highlights groups and individuals that targeted communication can potentially affect and creates a greater understanding into how past and current messaging has missed a mark and contributed to the fourth wave in Alberta.

SARS Experience Provides Pandemic Strategies

The SARS outbreak in 2003 received extensive media coverage, produced numerousofficial reports, and ultimately led to the creation of the Public Health Agency of Canada.Tyshenko and Patterson (2010) examine the lessons regarding risk communication learnedthrough the outbreak and recommend risk communication strategies to effectively manage apandemic. The book provides a history of the outbreak in Canada and around the world, detailsthe impact on health professionals, and outlines the failures rooted in communication to provide succinct recommendations for managing future disease outbreaks with effectivecommunication strategies. In Part One, Tyshenko and Patterson detail the history ofthe outbreak in Canada and examine how the medical community wasimpacted, how health professionals were affected, and how the coronavirus was transmitted.Social amplification of the disease, which they maintain resulted from fragmented public healthcommunication and media sensationalism (Tyshenko & Patterson, 2010, pp. 122–147), presenteda new risk to consider. Also considered in the comparative analysis is how officials in Singapore,Vietnam, Hong Kong, and China handled the outbreak, elucidating how different types ofgovernments handle disease crises and respond in a distinct, culturally mediated manner to anoutbreak.

Part Two focuses on risk communication. Tyshenko and Patterson (2010) consider the opinions of leading world infectious disease experts who sound the alarm about the world being unprepared for the “next” pandemic (p. 337). They predict the potential seriousness for Canadians of the next pandemic and provide a framework for response (p. 340), writing, “The scope of the next pandemic’s impact will be widespread, and those managing this risk will need to communicate useful information … media coverage will concentrate on increasing numbers of deaths and the impact to area hospitals hardest hit by a new viral strain” (p. 340). They recommend a “risk communication dialogue” among health professionals and governments to ensure public awareness of what is being done to safeguard people.

Tyshenko and Patterson (2010) accurately predict the next pandemic, which is currently being experienced. His observations of risk communications, and recommendations for clear and consistent information intended to help Canadians feel participatory empowerment, encourages concepts of knowledge and self-empowerment. Such concepts encourage buy-in and compliance with current government measures intended to reduce the viral spread of Covid-19 and apply to this research in this aspect.

Co-branding of Misinformation

A study of Instagram posts conducted in April 2020, and investigating co-branding of misinformation trends among posts related to Covid-19, identified a broad trend of general mistrust, including the conspiracy concept of government secrecy and fabrication of information. The survey considered posts that were co-branded with other types of misinformation, which makes post identity and removal more complicated. Quinn et al. (2021) state a better understanding of how misinformation is shared is integral to the ability of public health officials and policymakers to limit the spread of “potentially life-threatening health misinformation” (p. 573). While social media presents opportunities for public health officials to disseminate health information and influence behaviours, the spread of misinformation prompted the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare an Infodemic, an overabundance of information and misinformation. Quinn et al (2021) state: “The spread of misinformation is associated with increased deaths, wasted resources, delayed treatments, and increased concern associated with the already chaotic information landscape” (p. 573). The authors emphasize health information presented on social media can effectively influence health behaviours and risk perception, but also facilitates message amplification of rumour and misinformation (p. 573). The survey examined the top 10 Instagram posts, collected daily over 10 days from April 10 to 30, 2020, for the hashtags #hoax, #governmentlies, and #plandemic, resulting in an analysis of 300 posts which were coded for themes among images and textual responses. The authors conclude: “Overall, Covid-19 was frequently presented in association with authority-questioning beliefs” (Quinn et al., 2021, p. 573).

Quinn et al. (2021), asked what the dominant themes are with the said hashtags, and if there are lessons to be learned in Covid-19 posts on social media among those that co-branded with other “authority-questioning, skeptical, or conspiracy-driven hashtags” (p. 574). They note at the time of data collection, Canada had reported 55,601 cases of Covid-19. The U.S. had reported 870,000 cases. It was the height of the first wave of the pandemic. Instagram images were coded for content themes, with captions coded for accuracy, content, and dominant themes (p. 574). The most frequent broad themes identified were: general mistrust (43.8%); conspiracy theories (29.1%); unrelated (14.4%); anti-misinformation (6.5%); and quarantine (6.0%). The broad theme of general mistrust was further coded for sub-themes, which were government lies (20.9%); media lies (7.8%); do your own research (7.9%); and it’s a hoax (7.1%) (Quinn et al. 2021, p. 575). The top theme of government mistrust, which is identified as being co-branded with Covid-19, indicates a correlation with more negative attitudes regarding government pandemic response (Quinn et al., 2021, p. 575).

This study adds to the growing literature suggesting that social media is contributing to the idea that governments and the media are not trustworthy about Covid-19, and that social media users are being exposed to multiple examples of this trust-eroding material (Quinn et al., 2021, p. 573). This study provides a correlational basis for our research, and succinctly summarizes the top trends among misinformation on social media. The ability to identify the themes being disseminated on social media is integral to identifying the most effective counterargument messaging for public health and elected officials.

Before the emergence of Covid-19, the World Health Organization (WHO) identified vaccine hesitancy as one of the top 10 threats to world health. Understanding how vaccine hesitancy has been created and disseminated on social media, and through official governmental and institutional communication, is integral to supporting government public health messaging. The strategy behind and intention of public health messaging is vital to effective persuasive outcomes in a pandemic. Given the accompanying infodemic, which is a relatively new phenomenon in a public health crisis, such messaging needs to now be considered within the infodemic context. This research contributes to a growing body of academic literature informing public health crisis messaging during a pandemic and an accompanying infodemic.

Canada has experienced a public health crisis before, such as the SARS epidemic in 2003, but never before has a pandemic such as Covid-19 had global and all-encompassing societal impacts. In Alberta, protests, denialism, vaccine hesitancy, and underlying right-wing extremist views have resulted in a near collapse of the healthcare system as the province struggles to contain the virus’ fourth wave. It is vital in any crisis for communications from public officials to be clear and reassure the public of the government’s ability to manage it. Provincial crisis communications have been inconsistent, however. Messaging from Alberta’s Premier Jason Kenney ranges from that which borders on denialism to declaring the pandemic over before being forced to declare a public health emergency, and subsequently reinstituting containment measures. This research considers official communication and the public’s response to draw a correlation between the two to better inform the philosophies that guide crisis communications.

Methodology

Data was gathered through mixed methods content analysis of six Government of Alberta Covid-19 update videos posted on YouTube, and their corresponding social media comments from Facebook Live. Additional supporting data was gathered through the analysis of unique interactions related to the Covid-19 updates and other relevant content. Data collected from Facebook was gathered for qualitative textual analysis and statistical quantitative survey.

Six Government of Alberta Covid-19 update videos were analyzed out of over 240 videos. The six videos were chosen based on key times throughout the pandemic in Alberta, including the first state of emergency declaration, the announcement of strict lockdown restrictions during the second wave, and the “Open for Summer” campaign. Top comments and Facebook reactions were selected to survey the general population through unobtrusive observation and content analysis of social media comments. Specific themes that were flagged are flattening the curve, human rights, and vaccine safety. Corresponding keywords and hashtags include Covid-19, vaccine passport, anti-vax, lockdown, and distrust. Numerical data was collected through Facebook reactions, total number of comments, and total number of views.

Six Government of Alberta Covid-19 update YouTube videos were analyzed for key messages. Data was collected only on the speeches given by government officials. The analysis did not include the question-and-answer portion of the updates. The selected videos range from the start of the pandemic until September 2021: March 17, 2020; December 8, 2020; December 15, 2020; May 26, 2021; September 3, 2021; and September 15, 2021. Due to the unavailability of public response on YouTube, in which comments were turned off by the moderator, the research team used an alternate platform, Facebook Live, to view comments on these Covid-19 update videos. Comments on the Facebook Live videos were reviewed for analysis. Data collection provides quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative data includes the number of views per video, various health statistics provided by government officials during the videos and a count of the number of times the phrase “as Premier said” or a similar phrase was mentioned by government officials. Qualitative data included key messages and new health measures.

Transcripts for Covid-19 update videos are only available for Chief Medical Officer of Health Dr. Deena Hinshaw’s daily message. Due to the limited time of this project, it was not feasible to transcribe each of the six videos in its entirety and therefore, a count of specific words including “anti-vaccine,” “economy,” and “livelihoods” was not conducted.A list of themes was compiled and quotes from the videos were listed under the appropriate themes.

Social Media Analysis

Each data collection sheet was adjusted based on the individual needs of each Covid-19 update. The data sheets consisted of qualitative and quantitative data. Quantitative data included the total number of views, comments, and reactions made on each video post. Qualitative data was created based on an analysis of the contents of each individual “top comment.” Categorical data was expanded to be more inclusive of repetitive themes. Comments of interest were flagged and added to the document to provide more substantive data. See the appendices for a blank data collection sheet for the social media analysis and a completed data collection sheet for the social media analysis on the Facebook videos. Data was gathered by mixed methods content analysis. Keywords, informed by secondary research, were developed to identify variables. This study gathered data from two methods: analysis of six Alberta Government Covid-19 update videos and correlating public Facebook reactions and comments.

Video Analysis

- Six Government of Alberta Covid-19 update videos were selected, out of more than 240 videos, based on pivotal times throughout the pandemic in Alberta. They include the declaration of a state of emergency in March 2020, the announcement of strict lockdown measures during the second wave, the “Open for Summer” message, the $100 vaccination incentive program, and the announcement of a second state of public health emergency. The last announcement included the implementation of the Restrictions Exemption Program.

- Videos were analyzed, quotes transcribed, and data recorded on collection sheets for each.

- Comparative analysis identified themes for quotational evidence.

Social Media Analysis

- Facebook posts corresponding with the chosen videos were identified, and views, reactions, and comments were recorded.

- The top 100 comments were viewed and assigned to categories created by contextual content analysis, which provided relevant categories for further interpretation.

- Comments were cross-referenced for commonalities, repeated statements, or ideological bases.

- Once all comments were coded, the overall section was analyzed for correspondence to videos

Data Analysis

Data analysis occurred once all of the relevant information was gathered from the videos and social media. No software was used. Researchers coded text into the themes individually. Once the video and social media analysis was completed, researchers compared the information to identify overlapping trends, themes, and concepts. Content analysis of six video updates by the Alberta government, social media comments, and reactions by the public were examined to determine if the Covid-19 infodemic contributed to the current health crisis in Alberta by amplifying inconsistent messaging by provincial officials.

Results

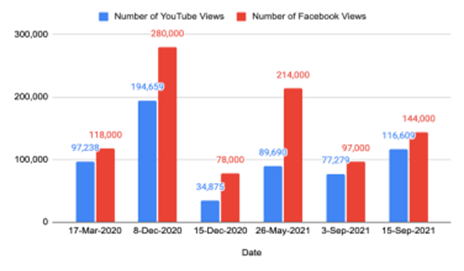

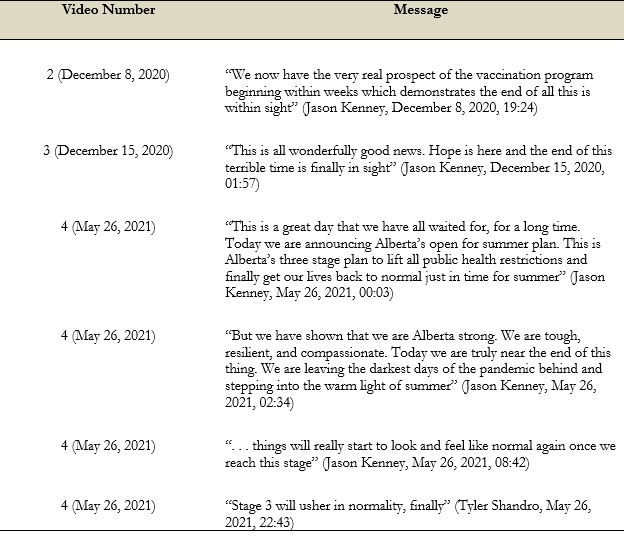

Qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analyzed from six Alberta Covid-19 update videos from March 17, 2020, to September 15, 2021. The correlating data from public comments are detailed in Figures 1 to 3 and Tables 1 to 7.

Video Analysis Results

The following figures, tables and themes reveal the results of watching the six Covid-19update videos.

Figure 1

Views of Covid-19 Update Videos

Figure 1 compares each of the six videos’ views on the YourAlberta YouTube account and Jason Kenney’s Facebook page. The view count was taken in November 2021, and the exact date is listed on each data collection sheet. The YourAlberta Facebook page does not archive the Covid-19 update videos; however, the public can watch the live updates there. The Government of Alberta website can only host nine videos at a time, and therefore, YouTube was where all six videos were analyzed. The December 8, 2020 update video had the most views on YouTube and Facebook compared to the other five videos. The total views over both platforms were 474,659 (194, 659 on YouTube and 280,000 on Facebook). The December 8 video introduces strict lockdown measures to combat the rapidly growing second wave of Covid-19. The May 26, 2021 update video had the second-highest viewership with a total of 303,690 (89,690 on YouTube and 214,000 on Facebook) views over both platforms. The key message from the May 26 video was the announcement of the “Open for Summer” plan. The December 15 video had the least number of views: 34,875 on YouTube and 78,000 on Facebook.

Government Officials Speaking in Covid-19 Update Videos

Attendance was taken for each of the six Covid-19 Update videos. Chief Medical Officer of Health, Deena Hinshaw, was present in five of six videos; Dr. Hinshaw was absent on May 26, 2021, for the “Open for Summer” video. This update was earlier in the day, and the health information was not yet available. Premier Jason Kenney was in attendance for five of the six videos and was absent for the Premier March 17, 2020 video (YourAlberta). He announced earlier in the day that Alberta was taking aggressive measures to reduce the spread of Covid. Minister of Health Tyler Shandro spoke in four of the six videos. Minister of Jobs, Economy and Innovation Doug Schweitzer appeared in two out of six videos. He appeared during the announcements on new funding for businesses.

Minister of Municipal Affairs, Tracy Allard; Minister of Community and Social Services,Rajan Sawhney; Minister of Justice and Solicitor General, Kaycee Madu, all appeared once for the December 15, 2020 video. Tracy Allard and Rajan Sawhney reiterated what PremierKenney said about COVID-19 Care Teams. Kaycee Madu mentions the importance of receivingaccurate information along with resources to prevent Covid-19 from spreading.

Alberta Health Services President and CEO Dr. Verna Yui appeared on September 3, 2021, and September 15, 2021. Alberta hospitals were facing severe capacity challenges, greater than any other time during the pandemic (Dr. Verna Yui, September 15, 2021, 34:57). On September 14, Alberta Health Services (AHS) reached 270 patients in ICU. Dr. Yui stated this is the highest number of ICU patients AHS has seen in Alberta’s provincialized health care system (Sept. 15, 2021, 35:09).

Theme 1: Redundant Messaging

Data collected summarizes the number of times a Minister or the Chief Medical Officer repeats the messaging from Premier Kenney. Kenney speaks first in the five of six videos he appears in. He provides a detailed overview of the pandemic situation in Alberta, including outlining new health measures, government initiatives and funding programs, sometimes making brief references to case numbers. In all five videos, other government officials speak after Premier Kenney. While watching the six Covid-19 update videos, a pattern began to emerge. During these updates, the other ministers often repeat what Premier Kenney states without providing significant additional information.

Analysis of data indicates Minister Tyler Shandro says “as Premier said,” “as Premier mentioned,” “as Premier noted,” and “as Premier outlined” at least once in the four of six videos he appears in. In the May 26, 2021 update video, Shandro uses “as Premier said” and “as Premier mentioned” a total of six times. Minister Shandro’s messaging is very repetitive to Premier Kenney’s update. The least use of the phrases by Tyler Shandro was in the September 15, 2021 update video. In this update, Premier Kenney provides minimal detail about the new public health measures, and therefore, Minister Shandro has more to contribute.

Minister Tracy Allard uses the phrase “as Premier stated” once and “as Premier mentioned” twice in the one video, December 15, 2020, that she appears in. Chief Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Deena Hinshaw, used “as Premier mentioned” and “as Premier noted” once. It appears that Kenney gives Hinshaw the most freedom to provide her update with minor redundancy from his own messaging.

Table 1

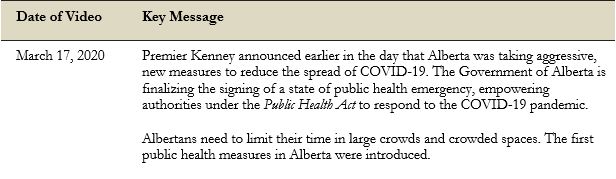

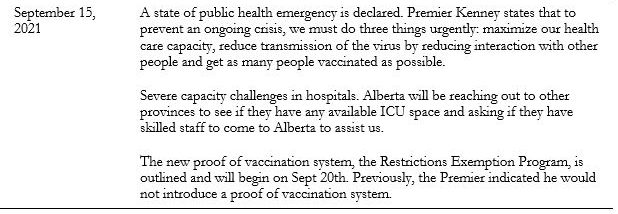

Video Summary and Key Messages

Table 1 provides a short description of the key messages from each video. The six videos were chosen based on pivotal moments throughout the pandemic while ensuring an equal number of videos from 2020 and 2021 were selected. Several themes were uncovered from the key messages delivered. Tables 3 to 7 examine the following themes: Premier Kenney compares Alberta to other provinces and countries, the Alberta government messaging divides Albertans, identifies the end of the pandemic is near, and definitive and distracting phrases and contradictions are used throughout the messaging.

Table 2

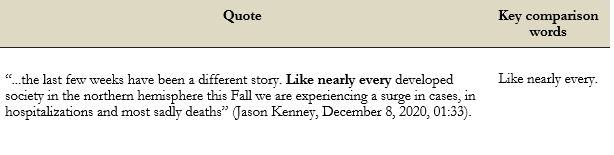

Premier Kenney compares Alberta to Other Provinces and Countries

Table 2 identifies instances where Premier Kenney compares Alberta to other Canadian provinces or countries to justify his decisions to date. When the Covid-19 situation is positive in Alberta, Premier Kenney celebrates his government’s efforts. When the Covid-19 situation is dire, Kenney seems to blame. In the December 8 update video, Kenney indicates Alberta is experiencing a higher rate of cases, hospitalizations and deaths. However, this is acceptable because all other developed societies in the northern hemisphere are in a similar situation. In the September 15 update video, Premier Kenney indicates that Covid-19 is hitting Alberta harder than every other province in Canada because of the low vaccination rates. He is steadfast that the Alberta government was diligent in their efforts to ensure Albertans got vaccinated. The low vaccination rates are not his fault.

Table 3

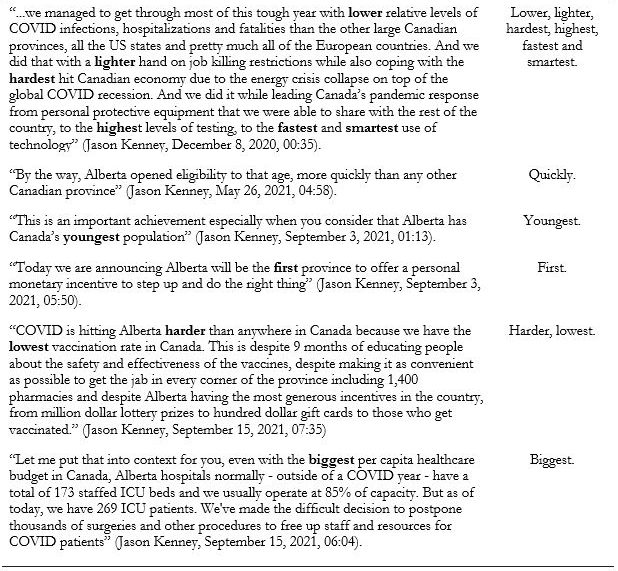

Theme 2: Dividing Albertans

Table 3 identifies the times Jason Kenney creates a divide between two populations of Albertans with his message. Minister Doug Schweitzer makes one comment that divides the public and small business owners in Alberta. In September 2021, as the Covid-19 cases increased and Alberta’s health care system collapsed, Kenney’s narrative began to set vaccinated Albertans and unvaccinated Albertans against each other. This divide does little for unifying the province in challenging times. Dr. Deena Hinshaw provides messaging that unifies the province. In the September 15 update video, the Chief Medical Officer of Health says, “I want to stress that no one sector or area of our society is driving this spread alone. Instead, it is the result of close contact that occurs wherever people gather together, especially indoors. This means no one sector is to blame” (para. 35-36). She goes on to say, “I ask all of us to go above and beyond the minimum requirements and to do everything we can to stop the spread. Our choices have never mattered more. The choice to be fully immunized saves lives. The choice to reduce close contacts saves lives” (September 15, 2021, para. 45-47). Dr. Hinshaw’s messaging unites Albertans; Premier Kenney’s messaging divides Albertans.

Table 4

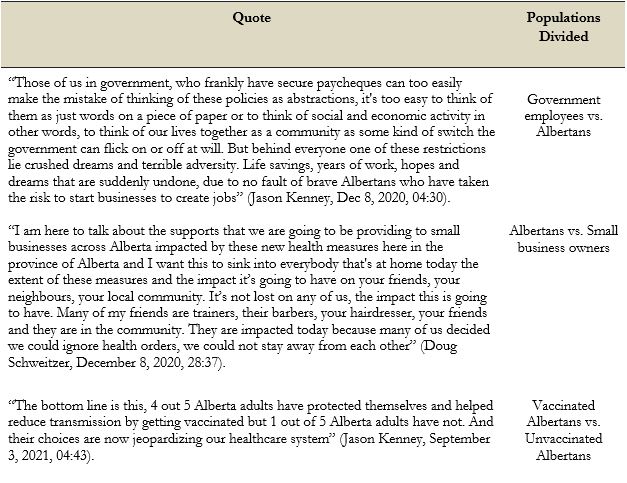

Theme 3: The End of the Pandemic is Near

Table 4 identifies the times Premier Jason Kenney made several early assumptions concerning the end of the pandemic starting in December 2020, this followed the public release of COVID-19 vaccines. Jason Kenney continues to reiterate a message conveying that Alberta will soon be at the end of the pandemic and that things shall soon return to normal. The message is repeated to give Albertans comfort in the “Open for Summer” plan. However, in September – after Alberta was open for summer – the cases steadily climbed, the tone changed, and there was no mention of the end of the pandemic again.

Theme 4: Definitive and Distracting Phrases

Jason Kenney speaks in a very definitive way, using phrases that are firm, final and authoritative. Statements like “the best Alberta summer ever” (Jason Kenney, May 26, 2021, 03:17) and “we will not let that happen” (Jason Kenney, December 8, 2020, 07:04) are not facts. They are overconfident statements used to embellish the messaging. The phrases distract, rather than provide accurate information to the listener. The language Jason Kenney chose to use allowed many individuals to be misinformed, leading to distrust of the Alberta Premier’s Communications

Theme 4 was also identified on The Bridge podcast with host Peter Mansbridge and guest Kathleen Petty. The Canadian journalist, Petty, discusses that Jason Kenney does not have the ability to be or appear humble (Mansbridge, 2021, 18:01). Petty discusses how everything Kenney says is big, absolute, and definitive – using terms like “best summer ever” or “open for good” (Mansbridge, 2021, 18:08).

Table 5

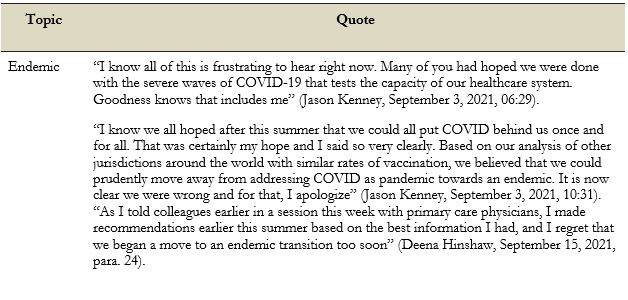

Theme 5: Contradictions

Table 5 includes quotations that were later renounced by Premier Kenney and Dr. Deena During both September 2021 video updates (video 5 and video 6), Kenney and Hinshaw admit that moving forward with the Open for Summer plan and transitioning from a pandemic to an endemic was a mistake. The Premier had made multiple public comments that he would not implement a vaccine passport in Alberta. However, on September 15, he announced Alberta would be implementing a proof of vaccination system, the Restriction Exemption Program. The contradicting messaging contributes to a lack of public trust.

Social Media Analysis

The following charts present data collected to determine the majority of reactions that individuals felt during or after viewing the Covid-19 updates on Facebook Live.

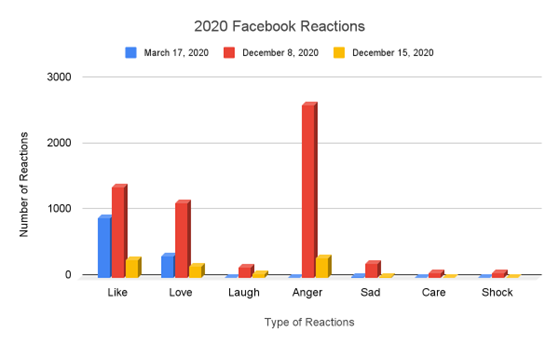

Figure 2

2020 Facebook Reactions

The March 17, 2020, Covid-19 update video titled “Covid-19 Update from Dr. Deena Hinshaw” on Facebook had 1,296 reactions. Most of these reactions were “likes,” with 908 of the 1,296 reactions being “likes.” This was followed by “loves” at 332, the “laugh” reaction at 13, the “sad” reaction at 22, and the “shocked” reaction at 12. There were no “care” reactions and nine “anger” reactions.

The December 8, 2020, Covid-19 update video titled “Stronger public health measures to save lives” on Facebook had 5, 679 reactions. Most of these reactions were “anger” with 2,624 of the 5,679 reactions being “anger.” This was followed by 1,374 “like” reactions, 1,144 “love” reactions, and 221 “sad” reactions. There are 160 “laugh” reactions, 73 “shocked” reactions and 83 “care” reactions.

The December 15, 2020, Covid-19 update video titled “Supports for Alberta Communities with High Covid-19 Spread” on Facebook had 2, 400 reactions. A majority of these reactions, 300 of the 2,400 total, were “anger.” This was followed by “likes” at 278, the “loves” reactions at 176, the “laugh” reaction at 61, and the “sad” reaction at 14. There were 9 “care” and 9 “shock” reactions.

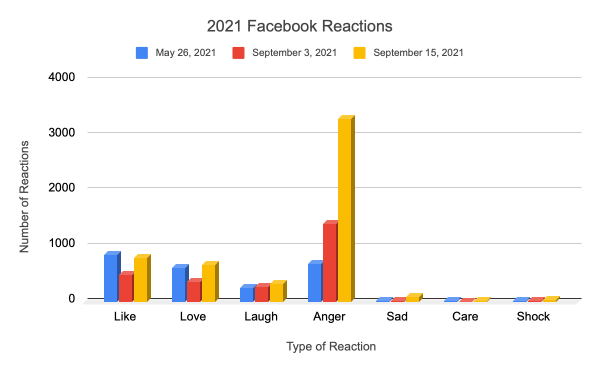

Figure 3

2021 Facebook Reactions

The May 26, 2021, Covid-19 update video on Facebook titled “Announcing Alberta’s #OpenForSummer Plan” had 2,521 reactions. A majority of these reactions, 853 of the 2,521, were “likes.” This was followed by 690 “anger” reactions, 632 “love” reactions, 253 “laugh” reactions, and 33 “shocked” reactions. There were 32 “care” reactions and 28 “sad” reactions.

The September 3, 2021, Covid-19 update video on Facebook titled “Update on Covid 19” had 2,651 reactions. Most of these reactions were “anger” with 1,419 of the 2,651 reactions. This was followed by 501 “likes,” 374 “love” reactions, 287 “laugh” reactions, 30 “sad” reactions, 26 “shock” reactions, and 14 “care” reactions.

The September 15, 2021, Covid-19 update video on Facebook titled “New Vaccine Requirements and Covid-19 Measures in Alberta” had 5,310 reactions. A majority of these reactions were “anger” with 3,313 of the 5,310 reactions. This was followed by 803 “likes,” 676 “love” reactions, 342 “laugh” reactions, 99 “sad” reactions, 47 “shock” reactions, and 30 “care” reactions.

Facebook Reactions Data Summary

Tables 6-7 identify the public’s interactions for each Covid-19 video update on Facebook Live. When comparing comments with reactions, results showed the most common reaction shifted to anger over time, with fewer and fewer individuals feeling sympathy, sadness, or shock. Reactions significantly correlated with the type of comment response given.

As more individuals reacted with anger the number of comments portraying disappointment, betrayal and doubt increased. Another common reaction was the “laugh” react, which was being used ironically, to express the individuals’ frustration towards the further developments of restrictions during the pandemic, and the hypocrisy felt towards certain behaviours being presented by the speakers and government.

Table 6

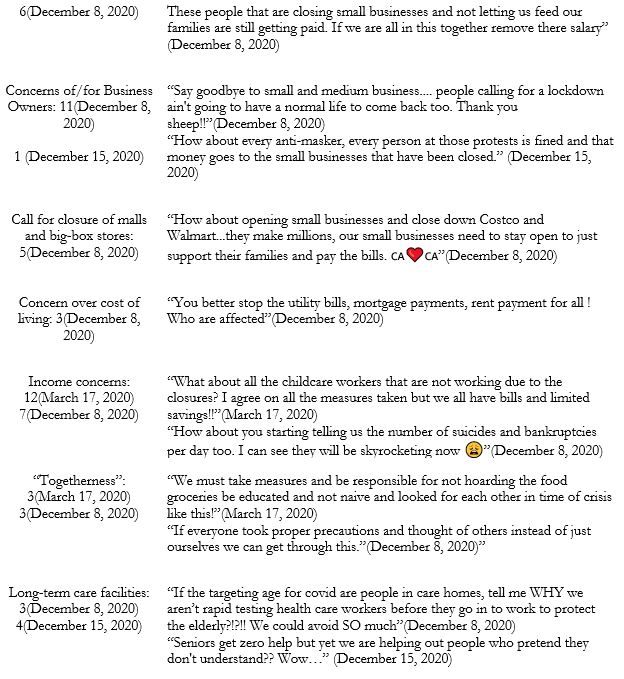

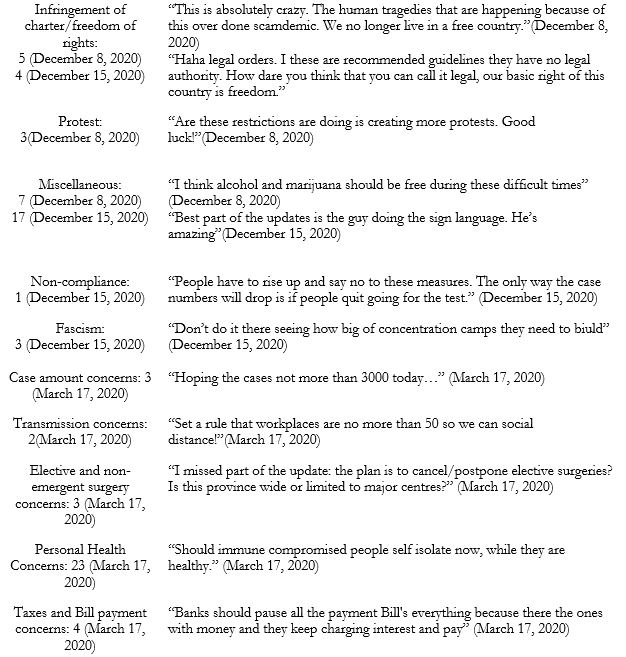

Facebook Comments: 2020

Table 6 includes examples of comments and the categories into which the “Top 100”comments were divided for 2020. In the March 17, 2020 video Many of the comments expressed concerns over the effects oflockdowns and periods of isolation on mental health and the impact of the shutdowns on smallbusinesses. Many criticisms directed towards Premier Kenney were to comment on his repeatedlateness to the “Live” announcements. Much of the criticism directed towards healthcare wasabout the ICU overload and how nurses and doctors also had to enter periods of isolation, furtherreducing the healthcare system’s capacity. Other healthcare criticisms were aimed at the closure of hospitals to the general public for non-emergent surgeries and treatments. Many individualsexpressed income concerns and demanded that Premier Kenney and other politicians take paycuts or suspend their income. The concept of “togetherness” also made headway in thecomments. The commenters encouraged others to refrain from protests and maintain properprecautions so that the situation could be remedied as soon as possible. Care homes were alsobrought up as a concern once again. Criticism of the government was largely connected toconcerns for mental health and income during the lockdown.

On the December 8, 2020 video comments in the category of conspiracy mainly related to criminal activities and training of the Chinese military as well as Covid-19 being a hoax and conspiracy about false-positive tests being made by individuals who were untested and non-Covid-19 related deaths being filed as Covid-19 fatalities. The miscellaneous comments stated politicians should have pay cuts. Several called out the potential lack of sanitation through each speaker change (placing used masks on the podium during speeches and not sanitizing the podium or microphone before usage). Comments that fell under that category of government criticism were primarily about Jason Kenney’s punctuality and lack of income support being provided for citizens.

For December 15, 2020, a large portion of the criticism in comments was directed at the governments because of their delayed response and inaction and many individuals were concerned about their source of income and cost of living. Additionally, many individuals wished for a lockdown to come sooner, stating that many other cities and continents had already implemented a similar strategy. Many individuals were concerned about the health of themselves and their familiars, stating that they wished to know more about the current numbers and the fatalities of the coronavirus. These commenters also hoped for further clarification on how restrictions affected those in camps and beauty businesses (hair and nail salons.) More than anything, individuals wanted to know more about the virus and the current restrictions being implemented. Several commenters also had concerns about border security concerning the quarantining of individuals coming from out of Canada.

Table 7

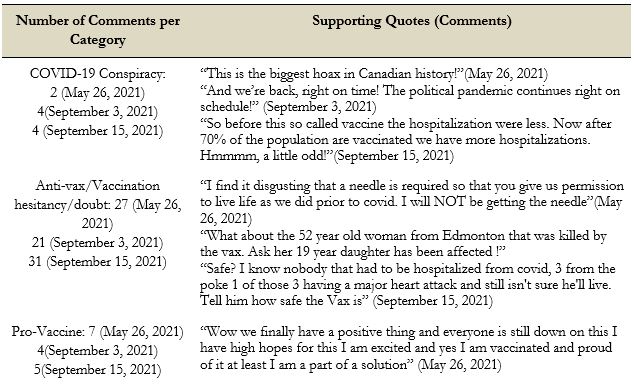

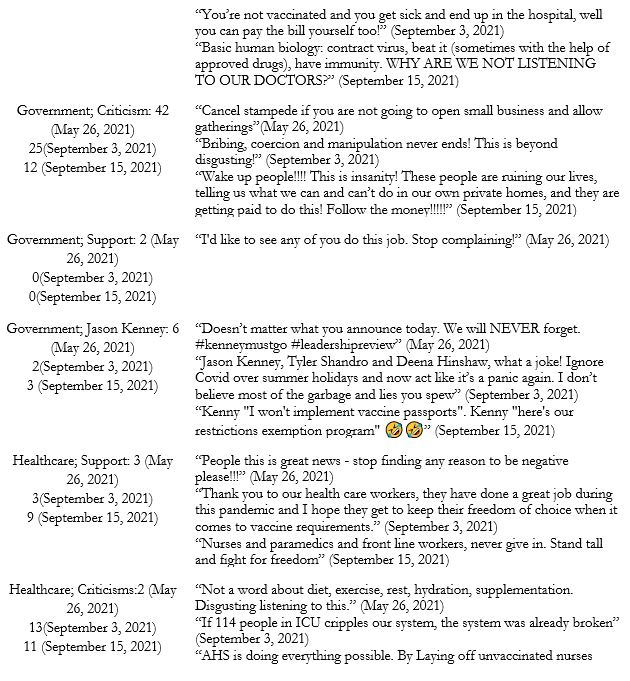

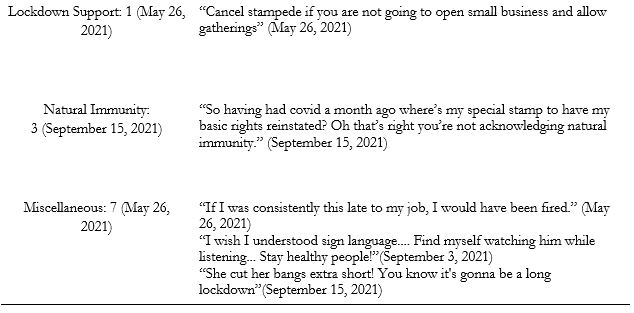

Facebook Comments: 2021

Table 7 includes examples of comments and the categories into which the “Top 100” comments were divided. On the video for May 26, 2021, the most overlap was between anti-vax/vaccine-hesitancy/doubt and the infringement of the charter/freedoms with governmental criticism. Many commenters criticized that the Calgary Stampede was allowed to proceed, but they were not allowed to have small gatherings and visit close friends or family. Criticism was targeted towards the announcement of the lottery and additional incentives. Many individuals thought that those funds would be better targeted toward the healthcare system and supporting small businesses. Other criticisms were commenters posting feelings of being manipulated and coerced into following restrictions and mandates. Most of the comments in support of healthcare are tied to comments in support of vaccination. Commenters specifically called for Jason Kenney to resign.

For the September 2, 2021 video a large portion of overlap was between Government criticism and infringement of the charter. Out of the 45 comments in criticism of the government, four specifically referred to Jason Kenney. Vaccine hesitancy and doubt also frequently overlapped with criticism of the health care system and was about relying on our borne and built immunity. “Do not comply” refers to cases in which commenters encouraged others not to mask, social distance, or follow other health care mandates, and stated that they would no longer be complying. Four comments under the category “Humanitarian concerns” contain allusions to fascism, segregation, and slavery. The one comment on religion stated that the commenter would have faith in their lord and the immunity he gave them.

In the September 15, 2021 video most comments in the category for vaccine criticism came from comparing case rates prior to vaccination and after vaccination. Many commenters felt that the vaccine was ineffective due to the increase in cases when compared to last year’s positive cases. In their eyes, the only significant change is the introduction of vaccines. Individuals that have natural immunity wished to have an exemption from the vaccine and doubted case numbers. Some commenters who owned businesses were not pleased to hear about the Restrictions Exemption Program. Many individuals called to take a stand against the implementation of further restrictions and voiced their feelings about not having a choice to become vaccinated.

Facebook Comments Data Summary

Tables 9 to 13 reiterate the same general opinions that the Facebook reactions do, mainly containing opinions portraying anger and concern. The comments found throughout the videos point toward the division of populations mentioned in the video analysis: vaccinated vs. unvaccinated, Albertans vs. the UCP, and small business owners vs. the government. Common themes in all the Covid-19 update video comments had to do with restrictions infringing on “The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms,” “forced” vaccination, and criticisms towards the healthcare system and current Alberta and Canadian governments.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The research reveals a definite resistance to pandemic measures among a sector of Albertans who voiced concerns, anger, and distrust in the official government narrative. This was further clarified in the following conclusions and recommendations.

Conclusions

Clear messaging and alternately, inconsistent messaging, impacts public compliance with crisis management. An infodemic, that is, an overabundance of information, misinformation, and disinformation (World Health Organization, n.d.) did not conclusively contribute to a Covid-19 health crisis in Alberta. Further research into cause and effect would be required to make such a conclusion. The data collected, however, did indicate inconsistent and divisive messaging from Alberta’s leadership contributed to a Covid-19 health crisis. According to the data collected in this study, the public responded to pandemic measures and their responses to public health crisis communication. Further, the data demonstrates the messaging from Alberta Premier Jason Kenney, Chief Medical Officer of Health Deena Hinshaw, and other government officials, was inconsistent and frequently denied the need for pandemic measures, followed by implementation of the measures. Themes of distrust and anger were identified as public responses to the inconsistencies and any implemented measures.

Crayne & Medeiros (2021) describe sensemaking as a process by which individuals interpret cues about their changing environments, utilizing the interpretation to explain what occurred and consider future actions. In a crisis, sensemaking is a means to collect information, provide an explanation, and develop appropriate actions, and is an “essential element to successful navigation of crisis events” (Crayne & Medeiros, 2021; Maitlis & Christianson, 2014, p. 463).

Tables 1 to 3 demonstrate the message themes disseminated by Alberta’s Premier, Jason Kenney, which effectively created confusion through inconsistency, divisiveness, and casting blame on other sectors and levels of government. The sensemaking process provides a framework for the public to understand the crisis. Such interpretation of a leader’s communication underpins public motivation to comply with measures, such as mask-wearing, social distancing, or vaccinations (Crayne & Medeiros 2021, Corley & Gioia, 2004, p. 464). Although Alberta’s messaging toward vaccinations was consistently pro-vaccine, urging Albertans to get vaccinated, most other messaging didn’t provide the foundational sensemaking needed to encourage compliance with public health measures and provided opportunity for less proactive messaging from less verifiable sources.

The government of Alberta’s messaging was strengthened by the frequency of updates, hard data, and Dr. Hinshaw’s unifying pleas. The message was weakened by Kenney’s frequent comparisons, divisive comments, definitive, distracting messages, and contradictions. Public reactions to official announcements and to the perception of government officials’ compliance with pandemic measures contributed to distrust and subsequent lack of support for pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical prevention measures.

Admitting a mistake is a level of honesty Albertans looked for as they attempted to make sense of the pandemic, and pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions. Premier Kenney, however, never fully acknowledges where he may have failed (Mansbridge, October 7, 2021, 19:24). Other messaging contributing to public trust or vaccine hesitancy includes that which was disseminated on social media—a great contributor to the changes in the public’s trust, reactions, and willingness to trust in the Covid-19 vaccines. At first, in March 2020, many individuals were eager to support the restrictions and regulations that were coming into place. Some commenters were hoping they would start sooner and be stricter. As time passed, commenters and viewers became more agitated, and a divide was created between members of the public (vaccinated/unvaccinated, small business owners/government, Albertans/the government, etc.). The public’s usage of the Facebook comments section opened the pandemic conversation to many other perspectives; it created a divide between Albertans and the government.

Comments encouraged vaccine hesitancy and doubt and challenged commenters’ views of the government and other figures in authority. Commenters frequently mentioned the vaccine “goalposts” that were set and how they could not see any loosening of restrictions despite passing them. The public was largely impacted by how the comments section was being used on Facebook; it amplified distrust and vaccine hesitancy, which continued to build as individuals shared their concerns.

Recommendations for Further Research

While the data did not definitely demonstrate how the premier’s messaging contributed to an Alberta Covid-19 infodemic, it did identify government messaging contributed to the expression of pandemic-related resistance views on social media, including the subsequently reduced rate of vaccinations among Albertans, and protests against non-pharmaceutical measures intended to limit the spread of Covid-19. Further research could identify the cause and effect more specifically and should include broader social media messaging perpetuated by misinformation and disinformation. Live surveys or interviews across a broad spectrum of Alberta’s population, and possibly using machine learning, would more expansively consider official government messaging, journalist inquiries, government responses to journalists, and the subsequent public reaction. Using algorithmic data investigation would also provide more substantive demographical data, including gender, race, age, and geographic location, and provide a more detailed cluster analysis of reactions to crisis communications and relevant reactionary behaviours. Such cluster analyses would enable a better understanding of the barriers to achieve successful compliance with public health measures. Given the limited amount of quantitative or qualitative research examining how the Alberta government’s crisis communications affected the pandemic’s case numbers, death, hospitalizations, and overall public health in Alberta, within the context of “What the heck is going on in Alberta? (Mansbridge, 2021), this research is a valuable contribution to the body of literature. Such contributions will enable future intervention effectiveness through a data-driven understanding of behavioural change-facilitation by communication.

References

Assaly, R. (2021, September 16). How we got here: A timeline of Alberta’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Toronto Star.

https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2021/09/16/how-we-got-here-a-timeline-of albertas-response-to-the-Covid-19-pandemic.html

Bernhardt, J.M. (2004). Communication at the core of effective public health. American Journal of Public Health, 94(12), 2051–2053. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.12.2051

Boucher, J., Cornelson, K., Benham, J.L., Fullerton, M.M., Tang, T., Constantinescu, C., Mourali, M., Oxoby, R.J., Marshall, D.A., Hemmati, H., Badami, A., Hu, J, & Lang, R. (2021). Analyzing Social Media to Explore the Attitudes and Behaviors Following the Announcement of Successful Covid-19 Vaccine Trials: Infodemiology Study. JMIR Infodemiology, 1(1), e28800. https://doi.org/10.2196/28800

CBC News. (2021, June 18). Ready to reopen: Alberta set to lift almost all health restrictions by July 1. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/jason-kenney-deena-hinshaw-Covid reopening-update-1.6070925

CBC News. (2021, September 15). Alberta to launch proof-of-vaccination program, declares health emergency amid surge in Covid-19 cases. CBC.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/kenney-shandro-hinshaw-update-Covid-19- 1.6177210

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2004). Identity ambiguity and change in the wake of a corporate spin-off. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.2307/4131471

Crayne, M. P., & Medeiros, K. E. (2021). Making Sense of Crisis: Charismatic, Ideological, and Pragmatic Leadership in Response to Covid-19. American Psychologist, 76(3), 462– 474. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000715

Dobson-Lohman, E., & Potcovaru, A.M. (2020). Fake News Content Shaping the Covid-19 Pandemic Fear: Virus Anxiety, Emotional Contagion, and Responsible Media Reporting. Analysis & Metaphysics, 19, 94–100. https://doi.org/10.22381/AM19202011

Fonseca, E. M. da, Nattrass, N., Lazaro, L. L. B., & Bastos, F. I. (2021). Political discourse, denialism and leadership failure in Brazil’s response to Covid-19. Global Public Health, 16(8–9), 1251–1256. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1945123

Griffith, J. A., Connelly, S., Thiel, C., & Johnson, G. (2015). How outstanding leaders lead with affect: An examination of charismatic, ideological, and pragmatic leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(4), 502– 517. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.03.004

Hansen, D.L. & Himelboim, I. (2020). Introduction to social media and social networks. In D. L. Hansen, B. Shneiderman, M. A. Smith & I. Himelboim (Eds.), Analyzing Social Media Networks with NodeXL (2nd ed., pp 3–10). https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/social-network-analysis

Hier, S. P. (2021). A Moral Panic in Reverse? Implicatory Denial and Covid-19 Pre-Crisis Risk

Communication in Canada. Canadian Journal of Communication, 46(3), 505–521. https://cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/3981

Hinshaw, D. (2020, March 17). Chief medical officer of health Covid-19 update – March 17, 2020 [Speech transcript]. Government of Alberta.

Hinshaw, D. (2020, December 8). Chief medical officer of health Covid-19 update – December 8, 2020 [Speech transcript]. Government of Alberta.

Hinshaw, D. (2020, December 15). Chief medical officer of health Covid-19 update – December 15, 2020 [Speech transcript]. Government of Alberta.

Hinshaw, D. (2021, September 3). Chief medical officer of health Covid-19 update – September 3, 2021 [Speech transcript]. YourAlberta.

Hinshaw, D. (2021, September 15). Chief medical officer of health Covid-19 update – September 15, 2021 [Speech transcript]. YourAlberta.

Hughes, B., et al. (2021). Development of a codebook of online anti-vaccination rhetoric to manage Covid-19 vaccine misinformation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7556. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34300005/

Hunter, S. T., Cushenbery, L., Thoroughgood, C., Johnson, J., & Ligon, G. S. (2011). First and ten leadership: A historiometric investigation of the CIP leadership model. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 70 –91. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342814871_Making_sense_of_crisis_Charismatic_Ideological_and_Pragmatic_leadership_in_response_to_COVID-19

Karstens-Smith, B. (2020, December 28). A timeline of Covid-19 in Alberta. Global News. https://globalnews.ca/news/7538547/Covid-19-alberta-health-timeline/

Maitlis, S., & Christianson, M. (2014). Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 57–125. https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/19416520.2014.873177