Students’ Opinions on Mandatory Vaccinations

Claire Buisseret, Samantha Hamann, Payton Konieczny

Abstract

Research conducted on this topic identified the perspective of MacEwan University Communications students and alumni on mandatory Covid-19 vaccination. The researchers believed most students would be in favour of, and have a positive outlook on, mandatory vaccination, but those who disagree will do so for issues regarding rights and freedoms. The data can be applied to understand perceptions and perspectives on public vaccination messaging. Potential influences on the choice to be vaccinated, such as age, where the individual is from, and their political stance, have also been analyzed. Research on this topic can inform vaccine companies and researchers about how the public understands their product and what factors in the vaccine’s messaging affect public perspective. This research circulated through MacEwan University Communications students and alumni through a program-wide email and a post on the Bachelor of Communication Blackboard course. These messages included a link to the online, voluntary, anonymous survey dedicated to perspectives on mandatory Covid-19 vaccination that was available during the Fall 2021 semester. Numerical and textual responses gathered from the study were analyzed based on the common patterns found within the group’s responses to the questions asked in the survey. Data collected from this research will be useful in identifying public perceptions of mandatory vaccination during the Covid-19 pandemic. This study found that most Communications students and alumni viewed mandatory vaccination positively for MacEwan University.

Keywords: mandatory vaccination, public perception, publicly accessible research, positive outlook

Statement of Purpose and Research Problem

Research conducted on the public perception of mandatory vaccination during the Covid-19 pandemic has been limited due to provincial restrictions, rapid testing processes, and the short timeline of the virus’ progression. Data collected from this study examines the effects of publicly accessible vaccine research and brand messaging. As public opinion is often shaped by advertisements and messaging, this research analyzes what factors may affect public perception regarding mandatory vaccination. Based on MacEwan University’s pre-semester poll used to determine what percentage of students and faculty are fully vaccinated, the researchers believe most Communications students view mandatory vaccination positively, but those who choose not to get vaccinated make that decision due to presumed issues regarding rights and freedoms. An online, anonymous survey was sent to Communications students and alumni to complete voluntarily during the Fall 2021 semester. Their responses were analyzed to find common patterns and possible correlations between influencing factors and their opinion on mandatory vaccination. The data has been used to measure how the students and alumni view mandatory vaccination. In this mixed-methods study, a numerical analysis is used to determine the prevalence of certain perspectives over others, and textual analysis is employed to discover patterns in the participants reasoning for their perspective.

Throughout the pandemic, vaccination has been a controversial, divisive topic. Although there is no ‘correct’ opinion, health officials urge everyone to get vaccinated to reduce the transmission, hospitalizations, and deaths caused by Covid-19. As a result, some have advocated that vaccination infringes on Canadian rights and freedoms. These groups believe their choice not to get vaccinated should not prohibit them from entering businesses, participating in events, and attending school. Since the emergence of the first Covid-19 vaccination, some groups have created theories that have made a greater divide among the population. This study allows vaccine companies and researchers better insight into the public opinion on vaccination and why the information and messaging surrounding vaccines has created a divisive topic in society. As Hu et al. (2021) emphasized, there are generally two outlooks on the Covid-19 vaccine. The first outlook is people favouring it because they believe vaccination will lead to less illness, death, and transmission. The second is that people oppose it because they believe it disallows the freedom of choice (para. 4). The importance of vaccine research and subsequent studies on public opinion aim to allow for a better understanding of what factors lead to the choice an individual makes regarding vaccination such as their political stance, age, and location and how they may play a role in shaping an individual’s outlook.

The data collected from this current study will also benefit MacEwan University. It could influence how classes are delivered and how proof of vaccination could be implemented to serve the student population better. As post-secondary institutions are beginning to require proof of vaccination to attend classes on campus, this data would provide an estimate of in-person class sizes. As shown by the research conducted by Reiss and DiPaolo (2021), colleges and universities could recognize new ways to incentivize students to get vaccinated by targeting specific influencing factors such as age. Age-based marketing, incentive programs, and proof of vaccination will increase vaccination rates allowing students to attend class but could also improve general impressions of mandatory vaccination (pp. 71-72).

Moving forward, this study could help to inform an individual that certain influencing factors do not need to play a role in their choice to get vaccinated. The data could reduce particular stigmas for individuals that are continuing to question vaccine ethics and efficacy. Although an entire population’s perspective cannot be easily or quickly changed, measures can be taken to target minimally vaccinated groups through educational campaigns to better inform general perceptions. These efforts could effectively increase public outlook on mandatory vaccination. The research from this study is important because it has the potential to influence how vaccine companies and researchers communicate their products to the public. As a result of influencing factors, personal opinion, and messaging issues being exposed, the companies will better understand what is shaping public perception. The research main question is as follows: What is the general outlook on mandatory Covid-19 vaccination among MacEwan University Communications students and alumni? The sub-questions include: Does age play a role in the decision to get vaccinated? Does political stance affect vaccination opinions? Does location (urban or rural setting) affect your perspective on vaccination?

Limitations of the Study

The limitations of this research are defined by the context in which the study was placed, the time constraints, access to participants, the biases of the researchers involved, and the articles examined within the Literature Review. The context for this research is deeply embedded in the current socio-political status of Alberta and its residents due to the Covid-19 pandemic that took a larger scale onset in March of 2020 (Assaly, 2021, para. 5). This context is defined within the Definitions section of this research study under ‘Alberta Government Pandemic Response’. As this is a relatively recent topic, the research was not as accessible or developed as it is for other viruses. This project was created, researched, analyzed, and finalized within three months of conception. Given this temporal constraint, the project is not as expansive as it had the potential to be and, as such, is the beginning of a much broader conversation. The researchers framed the research question to narrow the scope of the participants to an accessible and specific group for this study. The researchers of this study are students as well. Each with personal biases, influences, and opinions regarding vaccinations and mandates. One is asthmatic and prefers to avoid potential risks regarding respiratory diseases. One has worked in a retail drugstore throughout the pandemic and would prefer to minimize their risk of infection. One has a more conservative hometown but has made their own decision regarding vaccination. The limitations of this study affect the sample population, time frame of the study, and reach of this research.

Definitions of Key Terms

The key terms of this study are related to the primary topic of mandatory vaccination and Communications students’ and alumni’s perspectives on its implementation within MacEwan University. Terms are defined as they are utilized within the study, and parentheses will follow each with the term most used in reference to it if different from the one stated. The terms are defined in this order: Alberta government pandemic response, Covid-19, fully versus partially vaccinated, and vaccine exemptions.

Alberta Government Pandemic Response

The Alberta Government’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic has been a highly debated topic since the onset of the pandemic in March of 2020 (Assaly, 2021, para. 5; Wesley et al., 2020, para. 1). Support for the United Conservative Party (UCP) and Premier Jason Kenney’s leadership has significantly decreased throughout the duration of the pandemic, creating an increase of support for the Alberta New Democratic Party (NDP) and Rachel Notley’s leadership (Wesley & Snagovsky, 2021, Figures 2, 4, 5, & 8). Since March 2020, there has been a rotation of increasing and decreasing restrictions within the province to account for fluctuations in reported Covid-19 case numbers and vaccination rates of Albertans continuing through the completion of this research (Assaly, 2021, paras. 5-38). Each change in restriction had its own share of positive and negative responses with Jason Kenney and the UCP’s ‘Open for Summer’ campaign, which lifted all restrictions on the first of July 2021, becoming a prime target for commentary on the Premier and party’s response to Covid-19 in the Fall of 2021 (Anderson, 2021; Assaly, 2021, para. 20; Slack, 2021, paras. 2-4). Overall, the Alberta government’s pandemic response has been a topic with perspectives voiced from various political, professional, and personal backgrounds both outside and within the province.

Covid-19 (Covid)

A respiratory disease that, when contracted, can affect an individual’s breathing and/or sense of smell and taste. As well, the disease can have long-term effects on lung efficacy and their functionality (Johns Hopkins Medicine, 2020, para. 7-8). The spread of the disease took on a pandemic status in mid-March of 2020 (Assaly, 2021, para. 5). Since then, there have been endless social and political debates on lockdowns, masks, vaccines, and the ethical effects of creating mandates for each aforementioned factor. Covid-19 is a serious health risk because the impact and degree of the severity of the disease, although varying with each case, do not discriminate based on an individual’s previous health status (World Health Organization, 2020, para. 2). The impact of the disease can also create long-term respiratory and sensory complications for individuals that were infected, whether their reaction was severe or not.

Fully versus Partially Vaccinated

Since most currently approved vaccines are two doses, the difference between a partially vaccinated individual and a fully vaccinated individual depends on how many doses they have received. As well, the vaccines take at least 14 days, or two weeks, from injection to be fully effective (Health Canada, 2021; Liu, 2021, para. 3). Therefore, an individual that has both doses but only received the second one less than two weeks prior may also be considered partially vaccinated. The use of ‘booster’ doses for full immunization against the virus is currently being researched and so far is recommended for the immunocompromised (National Advisory Committee on Immunization, 2021, pp. 3-8).

During the time of this current study there were four strains approved by Health Canada. Each will be followed by a parenthesized name by which they will be referred to throughout the study. Moderna Spikevax (Moderna), Pfizer-BioNTech Comirnaty (Pfizer), and AstraZeneca Vaxzevria (AstraZeneca) are two-dose vaccines, while Janssen, or Johnson & Johnson (Johnson & Johnson), is a one-dose vaccine (Health Canada, 2021). By current standards, two doses were necessary to be considered fully vaccinated with Johnson & Johnson being the exception. However, after the completion of the study a booster shot, or ‘third dose’, was made available to the population over the age of 18 (Vasquez-Peddie & Neustaeter, 2021, para. 16-18).

Vaccine Exemptions

Validated reasons for an individual not to receive a vaccine, typically for medical or religious-based reasons. However, this exemption can be taken advantage of by some who do not want to receive a vaccine because they believe it infringes on their rights as an individual or because of their personal belief system. Some companies, both private and public, are taking the initiative into their own administration to mandate vaccination for all employees regardless of exemption status unless the individual wishes to take a rapid screening test on a weekly basis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021, “Vaccine Requirements & Exemptions”).

Study Summary

Public perception on mandatory vaccination is affected by publicly accessible vaccine messaging. The research for this study was conducted at MacEwan University through a survey completed by Communications students and alumni. The primary research question is used to determine how the participants view mandatory vaccination, and the sub-questions infer what factors may influence the decision to get the Covid-19 vaccine. The significance of the study is how this research has the potential to benefit MacEwan University and how it operates within subsequent semesters as a result of the pandemic. Terms used in this research are defined to create a concrete understanding of the material and how the keywords affect the comprehension of the study. Limitations of the study are also included to explain the time restraints, inclusion criteria, and personal biases of the researchers and participants of the survey.

Literature Review

The literature used and reviewed for this current study was created based on public and professional perspectives and reactions to mandatory vaccinations regarding how vaccines are developed, their global campaigns, and the ethical components of vaccination. For the purpose of this study, the sources used to explore public perspective base their findings on the opinions and reactions of the individuals that are making the choice to get a vaccine. Following the development and campaign messaging surrounding vaccination, potential responses to the vaccine are discussed. As later explained, encouraging vaccination involves pointing out all of its benefits to society. The sources discuss the economic, medical, and sociological benefits of a vaccinated world against Covid-19. Considerations of the ethical and motivational factors around mandatory vaccination are also outlined within the sources. This current study’s review of the literature on the outlook regarding mandatory vaccination is organized by the process of vaccine development, reactance to vaccination, ethics of mandatory vaccination for the public and healthcare workers, and vaccine campaigns and motivating factors.

Vaccine Development

As soon as scientists released the genetic sequence for SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19), vaccine companies began developing and testing different formulas of an mRNA vaccine. This information was released on January 11, 2020, and less than two months later, there were 115 vaccine candidates awaiting testing approval (Le et al., 2020, paras. 1-4). The Moderna mRNA vaccination was among the first to be approved to initiate human testing (para. 4). Although many vaccines were created and tested, few were successful in obtaining approval from the World Health Organization (WHO) in the fight against Covid-19. Of the approved vaccines, many were made as DNA or mRNA vaccinations due to their ability to create antigens and antibodies to improve the body’s immune response against the virus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021).

Le et al.’s (2020) study shows that private companies created 56% of the vaccine candidates, and 28% were produced through academic, non-profit organizations (para. 9). Although neither of these sectors had much experience creating mass amounts of vaccines at such a rapid pace, they believed in rigorous testing to ensure the safety of the vaccine’s use for the public. Most of the vaccine candidates were created in North America, so the guidelines of those countries also had to be adhered to in regards to production quality, safety, testing, and handling. A prominent supporter of the vaccine development process was the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), a global organization with the mission to accelerate vaccine development for pandemic and epidemic diseases, which communicated with “global health authorities and vaccine developers” (para. 2).

The researchers in this current study demonstrated the challenges that vaccine developers have had to face during this global health crisis in order to produce vaccines quickly and safely. In the future, vaccine creation will be improved for emergency use. Manufacturing capacity and regulatory practices will be increased in order to reduce development time for vaccines used to combat novel viruses (Le et al., 2020, para. 12). In order to improve vaccine efficacy in both short-term and long-term use, the development companies will be testing on animals to monitor how the vaccine could change once in the bloodstream (para. 14). Cooperation between governments, public health organizations, and vaccine developers will be necessary for ensuring rapid development, testing, and distribution plan as well as subsequent vaccination campaigns. Le et al’s article was included in this current research study to exemplify the struggle faced by vaccine development companies during the Covid-19 pandemic and how vaccine rollout strategies affect distribution, vaccination campaigns, and general vaccine acceptance.

Reactance to Vaccination

Sprengholz et al. (2021) studied the consequences of mandatory vaccines. The mental health aspect of mandatory vaccination is an important concept to keep in mind when developing policies for vaccination. Their study questioned whether or not the negative reactions and complaints towards the Covid-19 vaccines (before they were developed) and the current insufficient supply of vaccines, or halting of distribution altogether, were based on the same psychological mechanism of psychological reactance. This mechanism reflects an individual’s motivation to “regain the freedom lost,” as a result of mandatory vaccination (p. 987). For their first survey study, Sprengholz et al. focused their attention on subjects that were 18 to 74 years old, including 494 males and 479 females (p. 988). For the second study, the final sample size of the participants was 564 females aged 18 to 59 years old (p. 990). The researchers did not mention the statistics of the male participants or if there were any male subjects involved within the final study. As stated previously, the first study was conducted in a survey format:

Participants were asked what they would do if they had the opportunity to get a free vaccination against COVID-19 in the next week […] Participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions. In the unrestricted vaccination condition, participants should imagine that vaccination against COVID-19 was recommended but voluntary. In the mandatory vaccination condition, they should imagine that the vaccination was mandatory and that non-compliance would lead to a fine […] In the scarce vaccination condition, participants were directed to imagine that the vaccine was scarce and that they would have to wait until 2022 if they want to be vaccinated as elderly people and health professionals would be prioritized. (Sprengholz et al., 2021, pp. 988-989)

The second study took data from the first study and explained that mandatory and scarce vaccination can elicit reactance. Sprengholz et al. (2021) extended their findings to the consequences of the behaviour related to reactance. The second study was an experiment run in the same manner as the first with participants assigned randomly to one of three conditions: “Vaccination against COVID-19 was recommended, free of charge, and either unrestricted, mandatory, or scarce, depending on condition” (p. 990). Unlike the first study, the researchers gave a greater emphasis to vaccine scarcity.

Over 50% of participants from the first study had completed secondary education with university entrance qualifications. For the second study, over 60% of the participants obtained a college degree. The majority of the participants were Caucasian, followed by Asian participants, Black, and Latino. Sprengholz et al. (2021) explained that the results of their first study show reactance with stronger vaccination intent increased within the scarce vaccination condition and reactance decreased within the mandatory vaccination condition with the same level of vaccination intent (p. 989). In regard to the second study’s results, the researchers stated that “the more positive a priori vaccination intentions were the less reactance occurred given mandatory vaccination […] on the other hand, stronger a priori intentions were related to increasing reactance given scarce vaccination” (p. 991).

In the final summary of the study, Sprengholz et al. (2021) explain how the results of the studies confirmed their hypothesis that behavioural consequences of restricting freedoms for vaccination choices results in an increased intention to act against the elimination of said freedoms. Since the researcherss confirmed that their hypothesis was expressed in the manner they intended, they achieved the purpose of their experiment. However, Sprengholz et al. mention, “it is beyond the scope of this research to evaluate the ethical queries related to the implementation and communication of mandatory or scarce vaccination,” (p. 994). Despite this, they believe their findings will help social scientists and policymakers understand the mental effects of different vaccination procedures along with communication strategies to help stop the spread of Covid-19.

Sprengholz et al.’s (2021) research relates the findings from this current study as a result of the data collected from the survey created for MacEwan University Communication Studies students and alumni. The majority of the participants who had a positive perspective on mandatory vaccination policies were in favour because of how effective vaccination is in defending against Covid-19, the understood necessity to protect the immunocompromised, and their feelings of relief at having a vaccine available. However, there were still negative perceptions toward the vaccine. This current study relates to the source’s results of behavioural limitations in the context of restrictive freedoms for vaccination choices resulting in an increased intention to act against the elimination of said freedoms (pp. 991-993). This is related to those opposed to the mandatory vaccination policies who claim that mandates infringe upon the right to choose when it comes to vaccinations and bodily autonomy rights.

Ethics of Mandatory Vaccination

Giubilini (2021) uses his invited review to examine ethical issues surrounding behaviour and policies pertaining to vaccines. The variables within Giubilini’s study are vaccination and public health ethics (p. 4). Since Giubilini wrote this article while most vaccines were still in development, some of his phrasing around the topic is hypothetical. Giubilini states that “when we do have a vaccine that is widely available, COVID-19 will stop being a threat only if enough people are willing and given the opportunity to be vaccinated” (p. 5). He elaborates on this point by saying: “Vaccination decisions affect not only (or even not primarily) the individuals who get vaccinated, but also people around them and the community more broadly, vaccination decisions and policies are also ethical decisions” (p. 5). These quotes enunciate the fact that while getting a vaccine is a personal decision, it creates a butterfly effect on the surrounding community of each individual. Getting an immunization is not always something one does to protect themself. Receiving a vaccine for a disease can be a gesture of care for one’s community because it prevents the further spread of infection. However, as Giubilini points out, it is not always a matter of choice but sometimes an issue of access. He elaborates, by naming a few sample populations, that it is typically individuals of lower-middle-income nations who do not have access to vaccines and individuals of higher-income nations who choose not to immunize (p. 5).

As part of the review, Giubilini (2021) defines herd immunity as a public good, the principle of least restrictive alternative and vaccination policies, harm prevention, and fairness as points of ethical argument (pp. 6-10).

Herd immunity is when enough people in a particular population are immunized against a disease to effectively halt infection rates. In turn, this protects the smaller percentage of people unable to be vaccinated due to a medical exemption or because they may not be old enough. In the example of the current Covid-19 vaccines available in Canada, children aged five and under and immunocompromised individuals would depend upon herd immunity to protect them from infection (Government of Canada, 2021, paras. 1-7).

Giubilini (2021) states that, ethically, the prevalent perception of herd immunity is as a public good because it benefits the whole of the community directly and indirectly. But, herd immunity raises issues when brought against the principle of fairness and equal contribution to a cause (pp. 6-7). Essentially, the people who do vaccinate may find it unethical that those who did not receive a vaccine, even though they are medically able to, reap the same benefit as they, the contributors, do. Herd immunity works on a collective where each able person contributes.

Giubilini (2021) describes the principle of the least restrictive alternative and vaccination policies relating to achieving herd immunity and how a government can implement a plan without infringing upon individual liberties. Giubilini states that the following rights and freedoms are at stake with mandatory vaccination—bodily autonomy and choice regarding one’s health and the health of their offspring (p. 7). The following quotation adequately describes the central ethical conundrum within the least restrictive alternative principle: “It aims at promoting the collective good but also at preserving as much freedom as possible” (p. 8). However, this does not account for individuals who value their perceived freedoms much more than they care for the collective good. Giubilini concludes a similar point before opening his argument on harm prevention (p. 9).

Harm prevention is closely related to the principle of the least restrictive alternative based upon the least possible intrusion on an individual’s autonomy in promotion of a greater good, in this instance, the greater good of slowing/stopping further infections through vaccination (Giubilini, 2021, p. 9). ‘Do no harm’ is a fundamental principle in healthcare, so its correlation to public health crisis’ responses is not out of character. Individuals should scale the potential risks within vaccines against the harms, or risk of harms, in the spread of a disease among the population. (pp. 9-10). Overall, the debate stands on which side has less risk.

Ethical fairness rests at the core of each argument detailed above: fairness in herd immunity when not all contribute, and fairness in the least restrictive alternative and harm prevention where personal choice and community obligation meet to debate risk mitigation for either. Giubilini (2021) lists two requirements for fairness: “not to free-ride on a public good like herd immunity, when the public good exists; and (2) a requirement to make one’s contribution to a public good like herd immunity, regardless of whether the individual contribution ‘makes a difference’” (p. 10). Overall, fairness depends on equal contribution to collective benefit. Taxes to build public services exemplify the fairness principle; everyone who pays taxes funds something contributing to the betterment of their community.

Giubilini (2021) concludes his review by connecting the interdependence of individual, collective, and institutional responsibilities to vaccination ethics (p. 10). The most effective way to solve a problem is working with the parties around oneself and prioritizing a universal solution. His final line emphasizes the importance of maintaining the collective, individual, and institutional responsibilities at the forefront “with regard to vaccination decisions and policies […] at the centre of future philosophical, sociological and legal work on vaccination” (p. 11). Giubilini’s review was included within the current research study because it highlights arguments both for and against mandatory vaccination. Giubilini’s study also emphasizes how, ethically, major decisions such as implementing a mandatory vaccination regulation need to be made with considerations of the effects on all parties.

Ethics of Mandatory Vaccination for Healthcare Workers

Gur-Arie et al. (2021) wrote a commentary about the ethical issues regarding mandatory Covid-19 vaccination of healthcare personnel. The sample population includes all frontline workers (physicians, assistants, laboratory technicians, students in residency, etc.) who have directly and indirectly been around Covid-19 patients and have faced staff and resource shortages throughout the pandemic (p.1). The variables within the research are vaccine hesitancy among healthcare personnel (HCP) based on concerns of efficacy and perceived low risk of infection among personnel not working with Covid-19 patients. Their variables supporting mandatory vaccination for HCP include the principle of ‘do no harm’ and the duty of care involved with the healthcare industry (pp. 1-2). For the purpose of this Literature Review, it will focus on the ethical principle of healthcare which is ‘do no harm’. The main question of Gur-Arie et al.’s research is whether to mandate vaccinations for healthcare workers and how to implement it without a breach of ethics (pp. 1-2).

Policy should attempt to draw on current evidence, […] manage residual uncertainties, and prepare for future developments. On one end of the vaccine policy spectrum are less restrictive options—opt-in, voluntary recommendations, and so on—while on the other end, there are more restrictive options—compulsory mandates backed with legal and financial penalties, with non-compliance potentially resulting in imprisonment. (Gur-Arie et al., 2021, p. 2)

The above quotation outlines the different methods available to institutions when considering how best to implement policies to protect the individuals affected by their decisions, whether students in a university or staff in a hospital. However, any methodology chosen should be adequately measured against the risks associated with the phenomenon the institution wants to protect their staff or students against—in the case of the current pandemic, Covid-19 and the risks associated with receiving and not receiving a vaccine against it. However, the greatest benefit from vaccines comes from a significant sum of the population receiving their immunization and maintaining that significant percentage (Herd Immunity) — a feat where hesitancies would have to be put aside for the greater good of public health (Giubilini, 2021, pp. 6-7).

Gur-Arie et al. (2021) argue the principle of ‘do no harm’ as “one of the key justifications for requiring HCP to be vaccinated or show immunity against other documented occupational threats such as hepatitis B, measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria and pertussis31” (p. 3). The researchers’ point of ‘vaccines worked before, so keep vaccinating’ has objective support based on most of the aforementioned conditions significantly decreasing in frequency after their vaccines were developed and distributed. Debates on ethics suggest less intrusive methods for reducing transmission before implementing a vaccine mandate, such as increased personal protective equipment (PPE) (p. 3). However, a central characteristic of the pandemic has been the resource shortages experienced and the exposure to improper systemic protections, such as a lack of ventilation within healthcare facilities. Gur-Arie et al. argue that the “failed institutional responsibility to assist HCP in the fulfillment of their duties to ‘do no harm’ weakens appeals to such duties in the justification of vaccine mandates” (p. 3).

Gur-Arie et al. (2021) conclude that although a vaccine mandate for healthcare workers may be seen as an end-all-be-all for increasing vaccination rates, it does not equitably weigh all the associated ethical concerns (p. 4). Instead, they suggest that institutions start developing vaccine campaigns based on education to promote voluntary vaccinations, as most individuals prefer to make their own informed decisions. By facilitating vaccine-related conversation, institutions can hear healthcare personnel’s ethics concerns and their firsthand experience of a public health crisis (p. 4). Open communication around vaccination can lead to a similar approach with other private, public, and government-run institutions, which prioritizes education over coercion. This review was included within the research study because it highlights the importance of educating affected individuals on the reasoning behind instituting mandatory vaccination. Individuals are more likely to agree with something if given a valid purpose behind it because it makes the regulation less daunting and more reasonable.

Vaccination Campaigns and Motivating Factors

Researchers have found that the most effective way to combat the Covid-19 pandemic is through global vaccination. Covid-19 vaccines are used to “substantially reduce morbidity and mortality” within the general population (Deroo et al., 2020, para. 2). This correlates to vaccine companies’ aims to circulate their product safely and efficiently across the globe.

Deroo et al. (2020) believe that for the vaccine to reach its highest efficacy point, it must be available to healthcare workers and the general public to achieve herd immunity. However, the biggest obstacle to achieving herd immunity is vaccine hesitancy. This can be affected by publicly accessible vaccine research and the messaging behind it used to educate the public. It is believed that “a vaccine refusal rate greater than 10% could significantly impede attainment of this goal” (para. 3). Vaccine campaigns were created to educate the public about the need, safety, and goals of vaccination. The primary reasons for vaccine hesitancy and reactance are, “the necessity of vaccines, vaccine safety, and freedom of choice” (para. 3). Deroo et al.’s study demonstrated how enthusiasm for vaccination should be paired with a vaccine campaign and a vaccine distribution plan to ensure as much of the population as possible gets vaccinated quickly to decrease hospitalizations and deaths from the virus.

Although vaccine campaigns are effective in improving public perception of vaccination, some individuals still fear the rapid development and testing process behind the vaccine rollouts. Any potential safety concerns should be addressed in the publicly accessible vaccine information to reduce hesitancy and refusal among the public. Deroo et al. (2020) believe that the “contribution of individual vaccination to herd immunity” should also be included in the campaign to incentivize individuals to do what is best for the greater good (para. 5). Often, feelings of hesitancy toward vaccination reflect negative perceptions of the lack of time behind Covid-19 vaccine development and fears of experimentation for long-term effects yet to be fully discussed (Bogart et al., 2021, para. 5-79).

This study suggests that vaccination campaigns should utilize “traditional [mediums] and social media to engage” with the general public (Deroo et al. 2020, para. 7). This allows the vaccine companies, healthcare professionals, and political leaders to improve the accessibility of vaccine information. However, using social media may increase the chances of disinformation or misinformation spreading through the public regarding vaccination. Such theories and false information can be abolished through effective vaccine messaging.

The researchers conclude that “the groundwork for public acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine must be carefully started before a vaccine becomes available” to ensure optimal public acceptance and enthusiasm about vaccination (Deroo et al. 2020, para. 9). Vaccine campaigns must encourage the public to get vaccinated as soon as they can while “address[ing] known potential obstacles to vaccine acceptance using linguistically and culturally competent messaging” (para. 10). The messaging behind vaccine campaigns have the power to increase awareness of the benefits of vaccination and improve its public perception. This source was included in this research study to highlight the effects of vaccine campaigns on public perspectives of mandatory vaccination. Without such information, there would be a limited understanding of what publicly accessible information affects an individual’s decision regarding vaccination.

There are various motivations for someone to get vaccinated, but the most prominent are “to protect themselves and others, belief in vaccination and science, and to help stop the virus spread” (Dodd et al., 2021, p. 162). Certain groups have tended to favour vaccination more than others. These groups typically comprise healthcare professionals, residents of care facilities, the elderly, frontline workers, and the immunocompromised, as they face a greater risk if they contract the virus (Brüssow, 2021, p. 4).

Brüssow (2021) explained that “the only way out of the current health and economy crisis is widespread vaccination” (p. 10). Individuals who choose to receive the vaccine understand the necessity vaccination has on slowing down and eventually stopping this potentially life-threatening virus. “Successful vaccine roll-out will only be achieved by ensuring effective community engagement and by building vaccine confidence” through a positive public perception of vaccination established through effective messaging and transparent research (Brüssow, 2021, p. 11). Overall, those who are in favour of mass vaccination understand its importance in saving lives. This source was included in this research study as it reflects the questions asked in the study’s survey, which was used to collect quantitative and qualitative data from the participants regarding their potential influences on vaccination.

Contribution to Literature

This study grants post-secondary institutions insight into their student population’s perspectives on safety while attending classes during the Covid-19 pandemic. In addition to the existing literature surrounding the topic of mandatory vaccination, this study provides an understanding of potential influencing factors that may affect one’s decision to get vaccinated. Not only could this research benefit MacEwan University, but it could aid all educational institutions concerned about navigating restrictions, student and faculty safety, and learning in subsequent semesters. This research also provides information about vaccinations, their processes, and the ethical tensions around the decision-making process regarding a vaccine mandate. When it comes to vaccinations of any kind, people are generally split into two outlooks: pro-vaccination or anti-vaccination. With this research, readers can gain a better understanding of the value of population health over personal opinions. The study also provides education surrounding the stressful reality of vaccination developers rushing to get a safe and functional vaccine created for public use. This point could raise awareness for vaccine companies to analyze the divide between perspectives about vaccination and reassure those opposed using their own scientific data.

Review of the Problem

This research study is used to obtain a better understanding of how one portion of the MacEwan University student body and alumni population feels about mandatory vaccination and why they feel that way. Even though a small portion of the student body and alumni population were sampled, this study is an important step towards discovering how post-secondary students feel about a required vaccination necessary to further their education. Many variables influence the decision-making process to getting vaccinated against Covid-19. Possible variables include but are not limited to age, pre-existing health conditions, opportunities to attend in-person post-secondary education, travel regulations, and the type of vaccination available. A potential perspective that could arise after reading the literature surrounding this topic is that most, if not all, individuals desire a side-effect and financially free vaccination. With the research provided in this study, readers can obtain important information that can influence their motivation to get vaccinated and quicken the pace of a Covid-free world.

Methodology

This research study uses a mixed-methods methodology containing a content analysis of the survey. Mixed methods research combines the ideologies of both quantitative and qualitative research analyses to best suit the particular study (Creswell, 2014, p. 266). The methodology is designed for researchers, so they do not have to forgo a part of their research proposition in order to fit within either analytical perspective. Mixed methods take the poles of research and place them on either end of a spectrum to have the three paradigms of research working in a synthesized fashion. Combining research methods means the research can be continued and expanded upon by different disciplines.

Design

The study was structured as a digital survey. Creswell (2014) defines survey design as providing a “quantitative or numeric description of trends, attitudes, or opinions of a population by studying a sample of that population” (p. 201). The survey conducted in this study utilizes a mixed-methods approach by implementing open-ended and closed-ended questions to gauge statistics on Communications students’ and alumni’s perspectives on mandatory vaccinations and to examine the influences behind the statistics. The survey’s primary focus was analyzing different perspectives on the implementation of mandatory vaccination for all students and staff at the university. Survey questions were optional and non-invasive of the participant’s right to privacy and confidentiality. The questions centred on demographics (age, year of study, major, etc.) were used to determine any correlative data between background and/or personal context and perspective. Questions centred on perspective were used to examine the breadth and depth of perspectives held by students and alumni. The variation between open-ended and closed-ended questions is relatively balanced between the 15 questions with nine closed-ended and eight open-ended.

Sample

The sample of 49 participants for this study came from the population of Communications students and alumni at MacEwan University. Since there is no specific age group for this population, one of the questions in the survey asks for the participant’s age to determine if their generational position had a correlation to their perspective on mandated vaccines. Sub-groups within the sample came from Professional Communication majors, Journalism majors, and participants within the Public Relations program in different years of study within their program, as well as those from the alumni population. This sample from the university is diverse on its own, with an educational institute and similar programs bringing them all together. Individual backgrounds brought in a spectrum of choice and educational backgrounds as correlative factors regarding vaccination perspectives and the requirement of them to be on campus.

Instrument

The instrument used for this research study was an anonymous online survey with unique and topical questions about mandatory vaccinations and how the MacEwan University Communications students and alumni feel about the topic. The survey was conducted in Google Forms (see Appendix A). The survey was circulated through the Bachelor of Communication program email and a post on the program’s Blackboard course, reaching all current students as well as alumni of the program. Questions within the survey were developed through discussion of what would prompt participants to reflect honest perspectives, reasonings, and influences regarding their responses. The survey is a combination of multiple-choice, closed-ended questions and written response, open-ended questions. Once the email containing the survey and an extensive consent form was sent, the survey link was open and accessible to all recipients. The link remained active from October 28, 2021, until November 12, 2021, allowing participants to participate in the survey at their convenience to guarantee ample data collection. The survey was distributed once through an unretained collection of emails to ensure the data collected was not skewed by multiple responses from the same individual. The data is assessed based on both its numerical statistics from the multiple-choice questions based around demographics and on a scale of connectivity from the open-ended questions within the survey. It is also assessed through content analysis using the response information that the survey program provided quantitatively (see Appendix B). The researchers deciphered differences, similarities, and correlative aspects between the responses as detailed within the Conclusion and Discussion portion of this study.

Procedures

Data Collection

To collect data for this research study, the researchers developed a survey to gauge the participants’ demographics, vaccination influences, and overall views on vaccination. Data for the survey was collected through the Google Forms’ response section. The responses were collected through the survey, which was attached to an email sent out to the MacEwan University Communications students as well as the alumni of the program. The survey included an in-depth consent form with a required checkbox to confirm or deny consent to participate prior to the presentation of the questions. Participants were able to exit the survey at any time without the need to complete it. After the survey was closed on November 12, 2021, the results were electronically grouped and analyzed by the researchers.

Data Analysis

The statistics from the survey were analyzed through a mixed-methods content analysis. First, the quantitative breakdowns of the multiple-choice questions provided were analyzed through graphs created by the survey program and the researchers to group similar demographic responses regarding major and year of study. Then, the qualitative findings of relations and themes between the participants’ answers were examined and grouped with similar responses to create graphs depicting the common range of responses. The original, ungrouped responses to the qualitative questions can be found in Appendix B. The researchers explored the possible fluctuations of perspectives based on the participants’ generations, year of study, personal backgrounds, and other factors relating to the results of the survey. After the data was collected and organized, the researchers were able to create a more accurate description of the views and perspectives of MacEwan University Communications students and alumni in the context of mandatory vaccinations.

Summary

This research study used a mixed-methods methodology, including a content analysis of the survey results. The researchers found qualitative relationships and themes between the participants’ answers. Then, they explored the fluctuations of perspectives based on the students’ generations, year of study, personal backgrounds, and other factors correlating to the survey results. The researchers used this data to create a better understanding of the perspectives of the Communications students and alumni from MacEwan University regarding mandatory vaccination policies and procedures.

Results

The survey consisted of 15 questions. The first five are demographically based, the next three are Covid-19 vaccination status and influence based, and the final seven are opinion and perspective based. Nine questions are closed-ended, with five having an option to write in a response. Six questions are open-ended, with two using a short-answer format and four using a long-answer format. Quantitative questions were used to collect statistics regarding participants’ answers, and qualitative questions were used to collect participants’ perspectives. Each survey question adds to the research by determining the affective factors for each participant and/or how the affective factors may have impacted or shaped the participants’ perspectives regarding vaccination and making the Covid-19 vaccination mandatory.

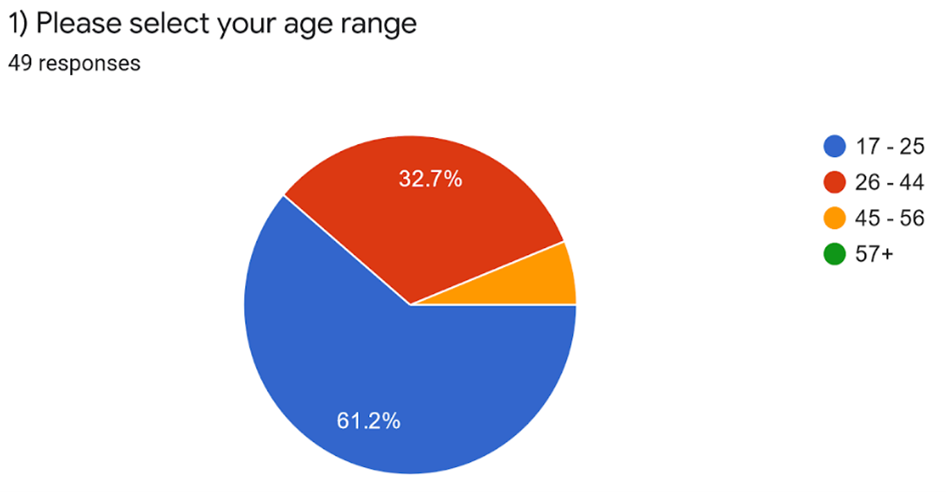

Figure 1

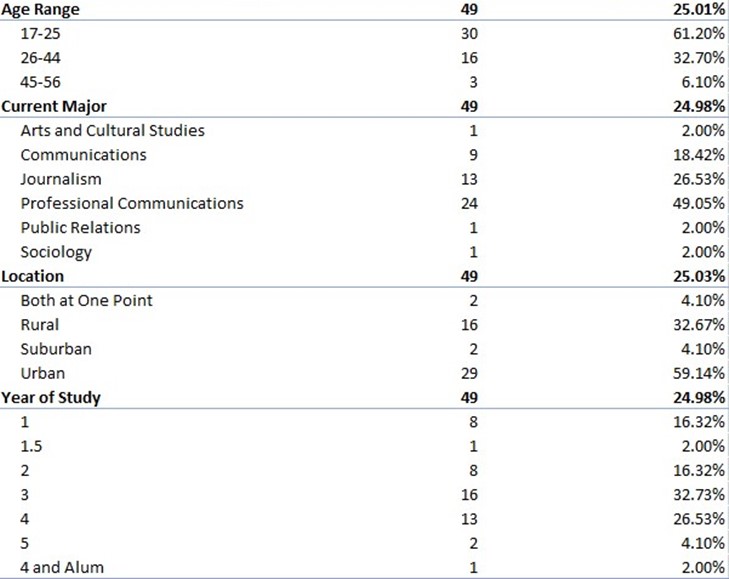

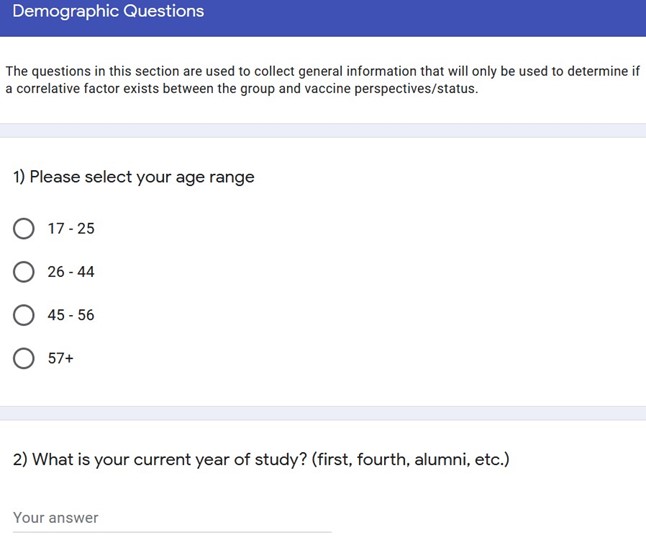

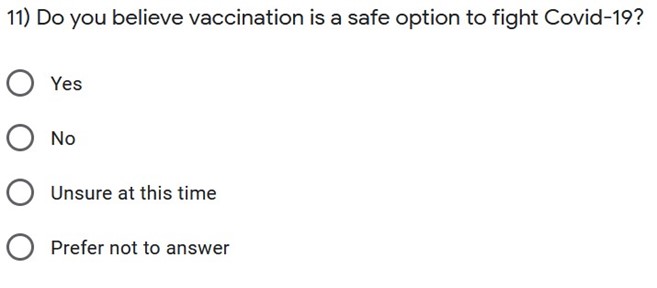

Question 1: Please select your age range. — 49 responses

Question one received 49 responses that varied between ages 17–56. Thirty of the responses (61.2%) fell into the 17–25 age range category. Outliers of this question are three participants (6.1%) falling into the 45–56 age range (see Appendix B). This common age range was not unexpected as the participants are university students and alumni from the Communications Studies program, which began in 1999 at MacEwan University.

Question 2: What is your current year of study? — 49 responses

Question two received 49 responses. Sixteen of the participants (32.7%) identified as third-year students. The outliers for this question were one participant (2%) who identified as a ‘one and half year’ with their second year beginning in the Winter term and another participant (2%) who identified as a fourth-year and alumni.

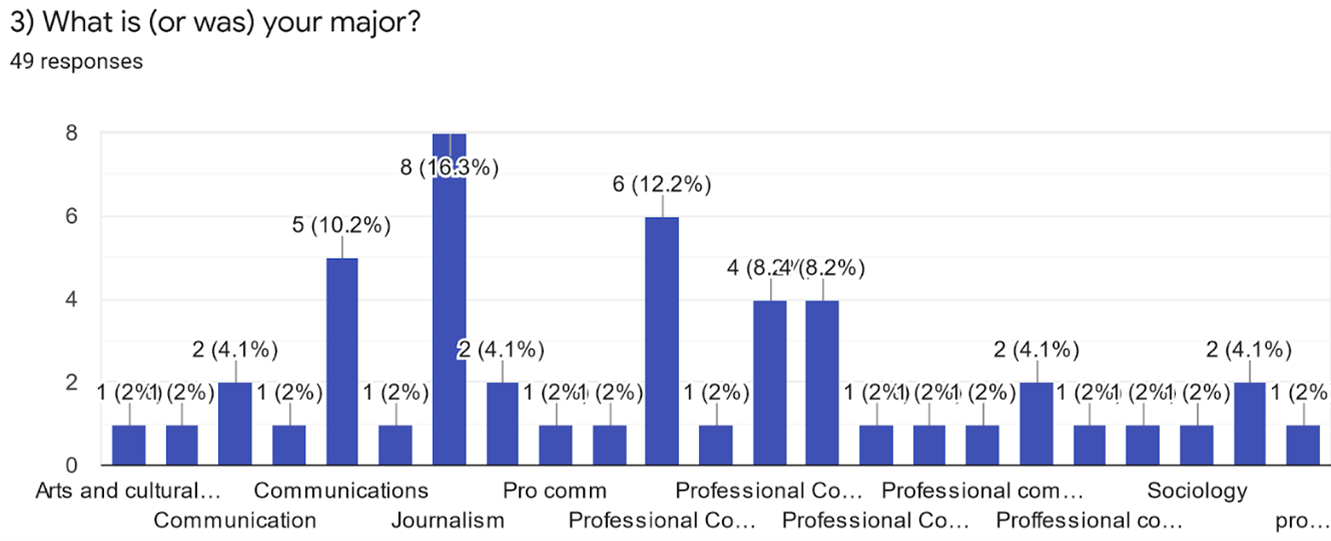

Question 3: What is (or was) your major? — 49 responses

Question three collected 49 responses. The most common answer was Professional Communication with 24 responses (48.9%) followed by Journalism with 13 (26.5%). Included in the common range of answers were Communications with nine responses (18.3%), as well as Sociology, Arts and Cultural Management Studies, and Public Relations, each receiving one response (2% each).

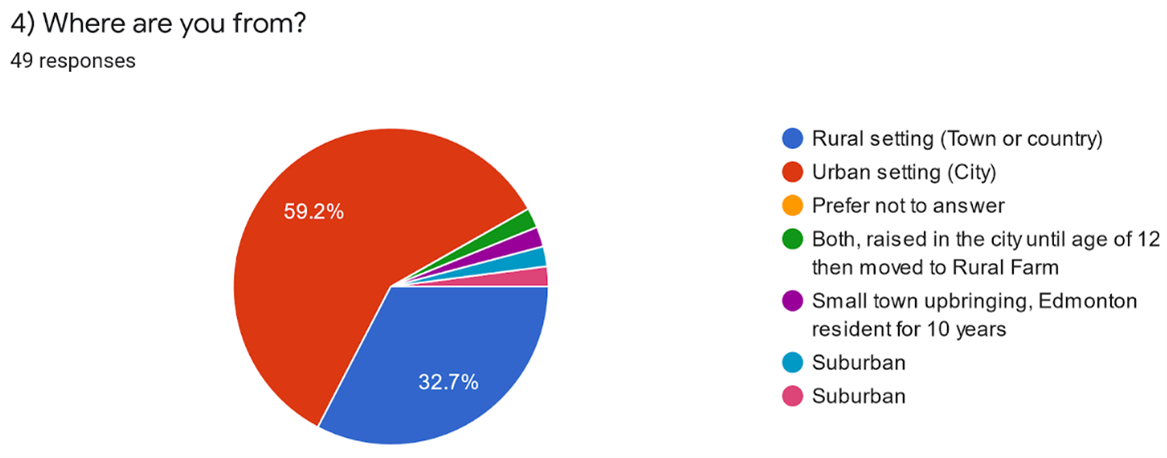

Question 4: Where are you from? — 49 responses

Question four gathered 49 responses. The most common response was the ‘Urban’ setting with 29 responses (59.2%). ‘Rural’ was the second most common answer with 16 responses (32.7%). The outliers from this question were two participants (4%) choosing a ‘Suburban’ option, one participant(2%) picking a small-town upbringing but current ‘Urban’ resident, and one participant (2%) choosing both ‘Urban’ and ‘Rural’ settings. No one chose ‘Prefer not to answer.’

Figure 2

Question 5: Which political party did you vote for in the 2021 Federal election? — 49 responses

Question five received responses from all 49 participants. The most common response for the participants’ political stance fell into the New Democratic party category with 30 responses (61.2%). The second most common response was from the six participants (12.2%) who voted for the Conservative party. The outliers from this question are two participants (4%) who voted for the Green party during the 2021 Federal election.

Question 6: To what extent are you vaccinated against Covid-19? — 49 responses

Question six received 49 responses. Forty-three participants (87.8%) identified as vaccinated with two doses. At the onset of the survey, 32 participants (65.3%) identified as two-dose vaccinated. There were two participants for each category of one dose, not at all, and two doses and a booster (4% each). As MacEwan University mandated all students must be fully vaccinated before the beginning of the 2022 Winter term, the majority of participants being two-dose vaccinated is not unexpected.

Question 7: If you have been vaccinated, which vaccine(s) did you receive? Check all that apply. — 49 responses

Question seven gathered 49 responses. The Moderna and Pfizer vaccines maintained an equitable lead throughout the duration of the survey, with the two ‘non-applicable’ participants (4%) coming from the beginning of the survey period. The majority of participants did not mix vaccinations and opted for two doses of Pfizer or Moderna. The three responses (6%) with an AstraZeneca mix also came from the onset of the survey. The outliers, or least common responses, for this question are the participants who mixed vaccines or who did not receive a vaccination at all.

Figure 3

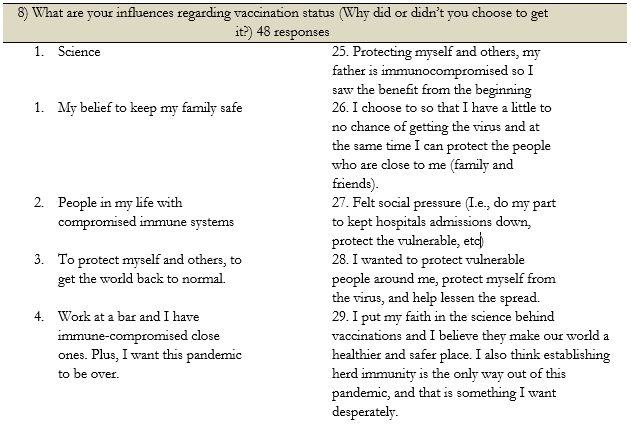

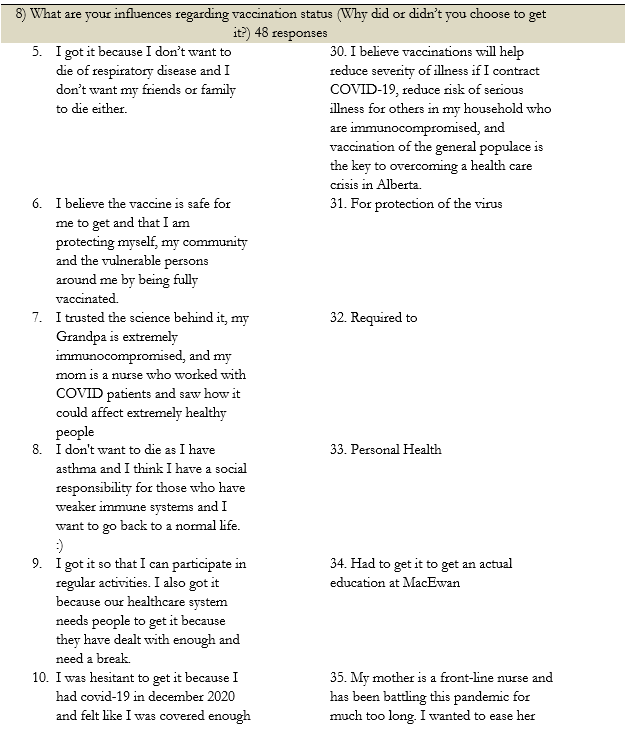

Question 8: What are your influences regarding your vaccination status? — 48 responses

Question eight received responses from 48 survey participants. This question has five outliers (10.4%) with one response each: travel, reducing the severity of Covid-19 if contracted, mandatory for employment, hesitant because there have been no long-term studies conducted and a belief that the vaccine is unnecessary for young, healthy people. The most common influence for participant vaccination status is protecting personal health during the pandemic; this category received ten responses (20.8%). Other responses fell into the categories of protecting family, immunocompromised, and society as a whole. This question proves that everyone has different influences regarding their vaccination status. Throughout the survey, the individually unique responses differed but mainly reflected a desire to protect themselves and their loved ones.

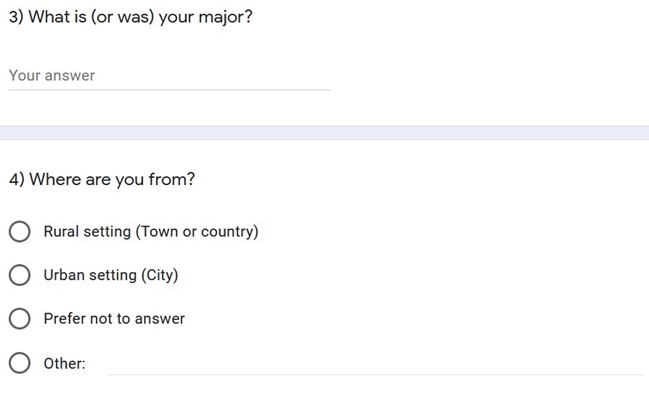

Figure 4

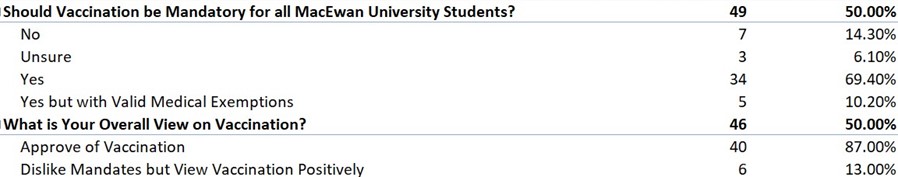

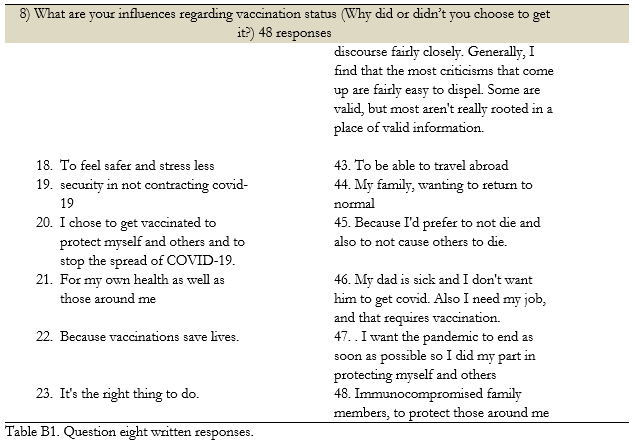

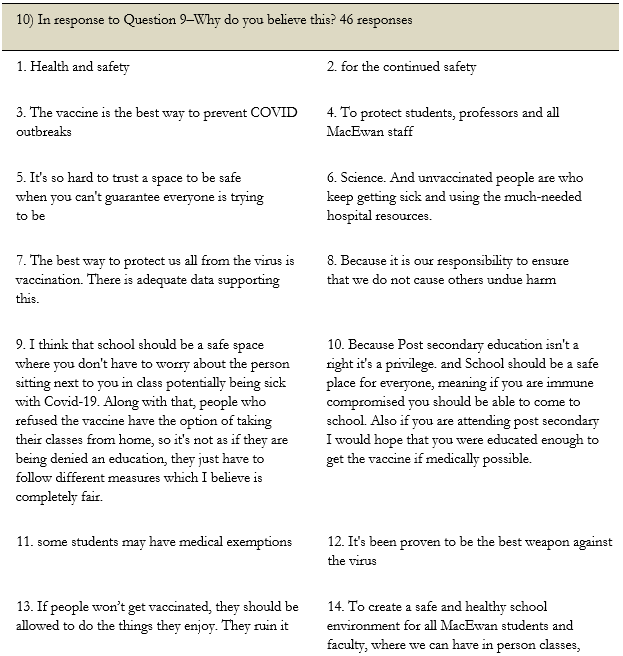

Question nine: Should vaccination against Covid-19 be mandatory for all MacEwan University students?— 49 responses

Question nine collected 49 responses. The most common response was ‘Yes,’ for students and alumni favouring implementing a mandatory vaccination policy for MacEwan University. The ‘Yes’ response had 34 responses (69.4%). The second most common answer was ‘No’ with 7 responses (14.3%) (Figure 4). Three participants (6.1%) picked the ‘Unsure’ option on the survey. ‘Yes except for medical exemptions’ consisted of five participants (10.2%).

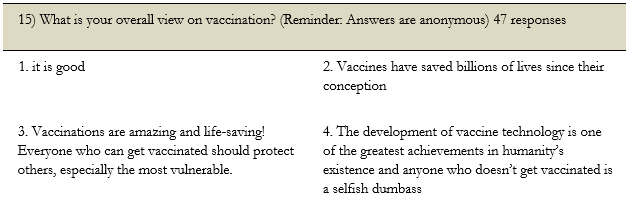

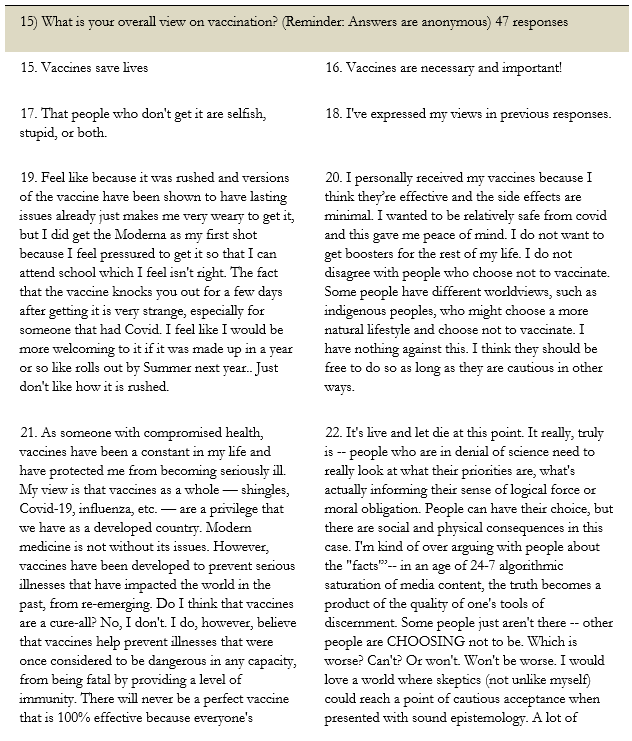

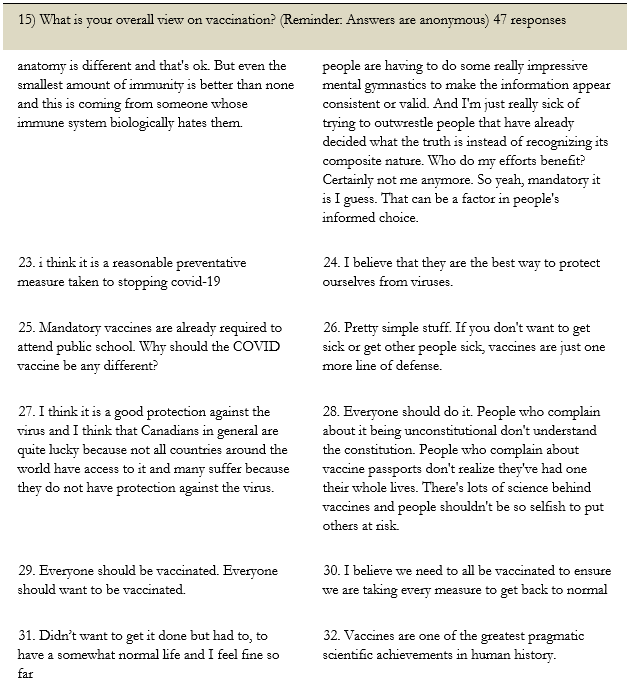

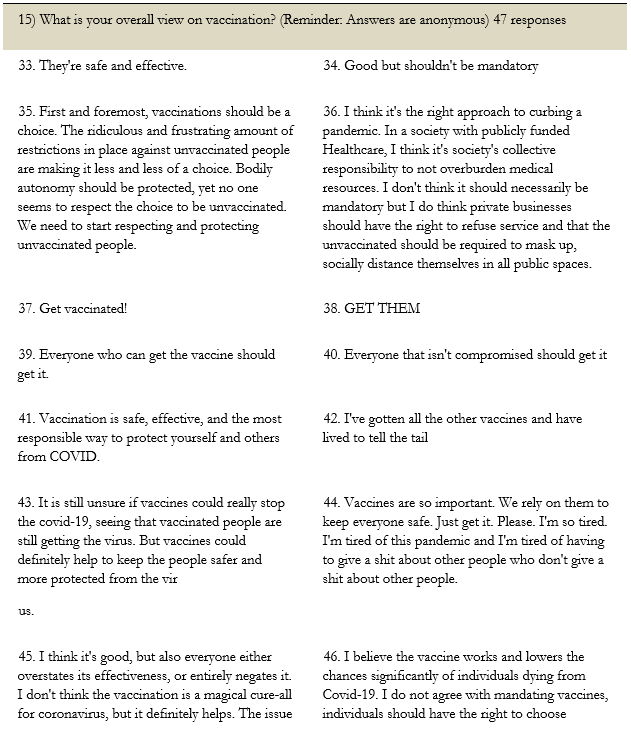

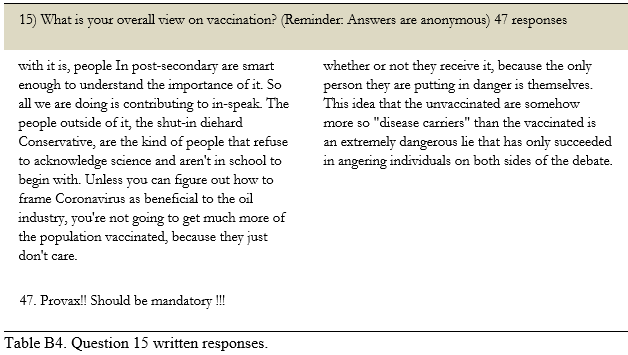

Question 15: What is your overall view on vaccination? — 47 responses

Question 15 gathered 47 responses. The outlier from this question was one response (2.1%) that said, “I have expressed my views in previous responses.” None of the participants answered that they disagreed with vaccination (see Appendix B). However, six participants (12.7%) responded that vaccination positively affects society, but it should be a personal choice to become vaccinated rather than a mandate. The participants who viewed a vaccine mandate negatively explained that it went against their bodily autonomy rights to make their own decisions about their health. Forty of the participants (85.1%) approve of vaccination and have a positive perspective on the matter. During the period in which the survey was conducted, the general perspective on mandatory vaccination remained almost entirely positive and pro-vaccine mandate.

Figure 5

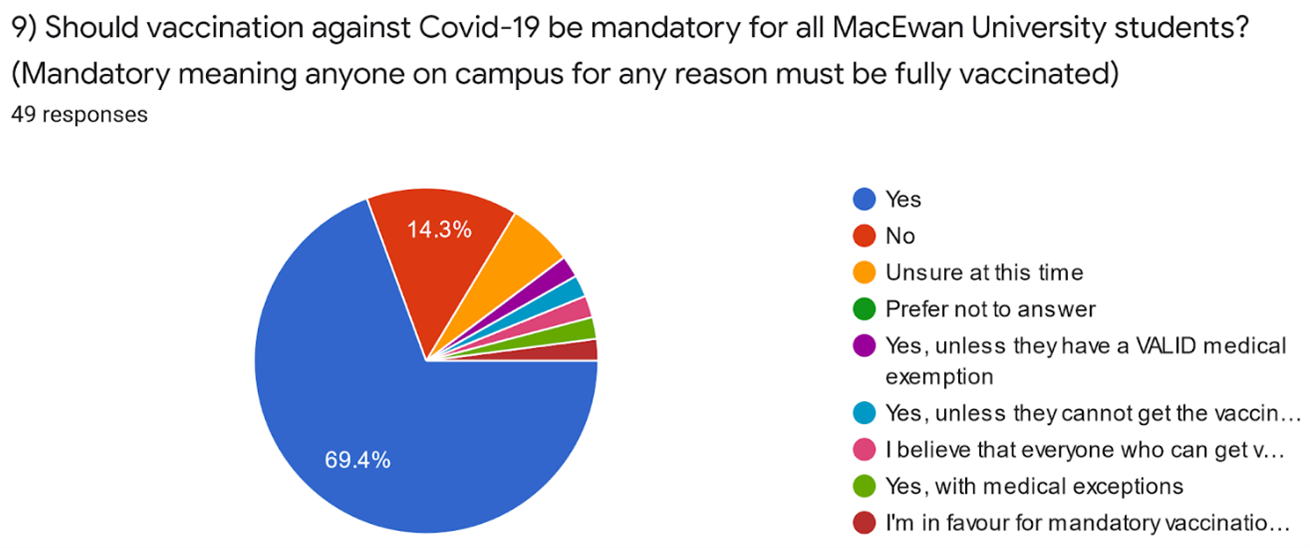

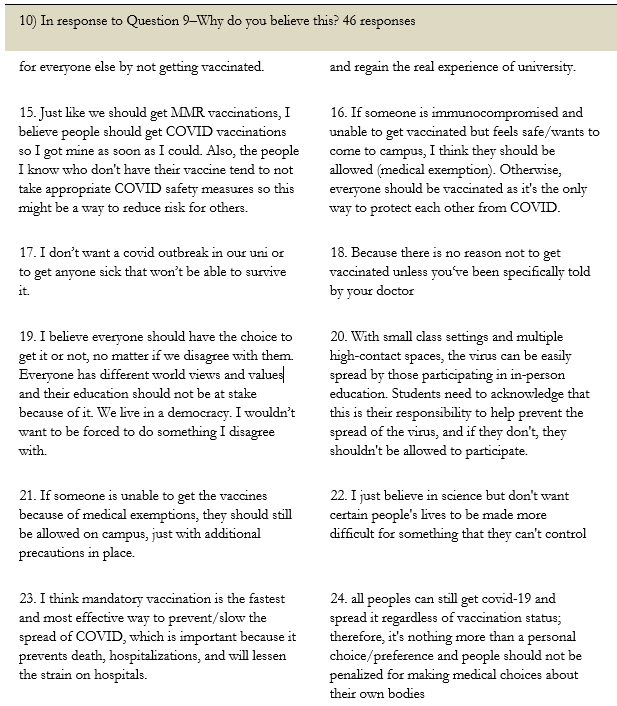

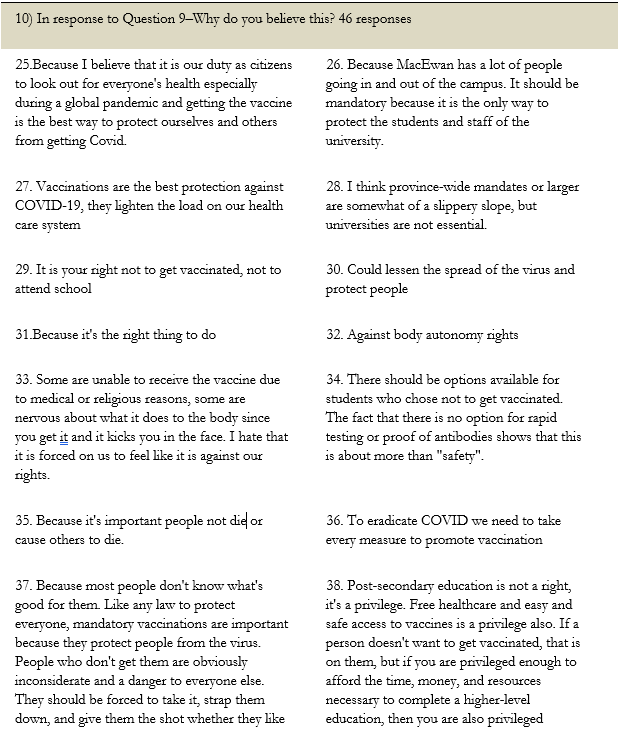

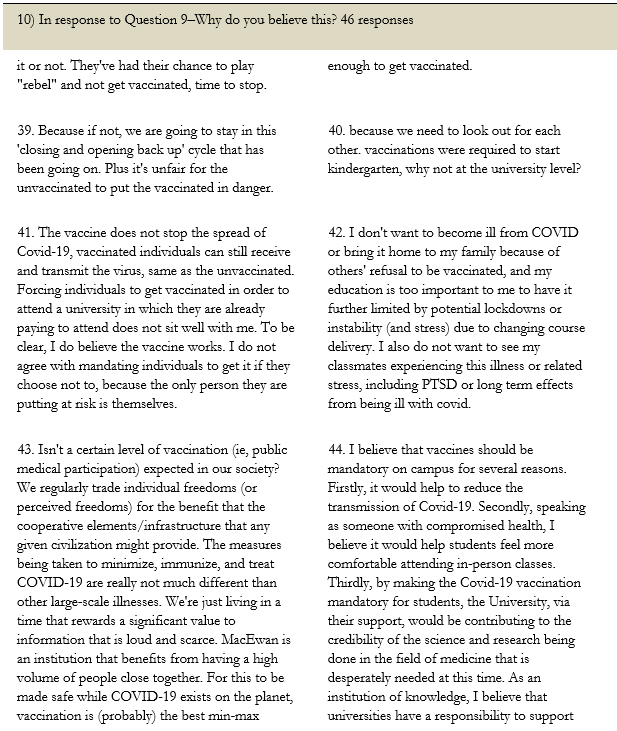

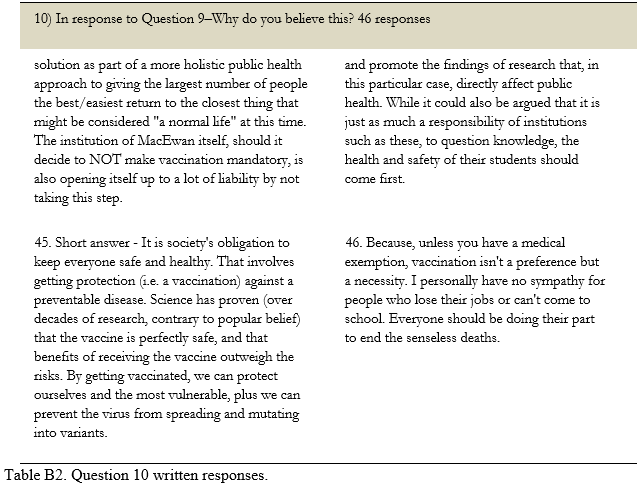

Question 10: In response to Question 9 – Why do you believe this? — 46 responses

Question 10, which was in response to question nine, received 46 responses. The most common type of response was related to public or civil responsibility. Twenty participants (43%) provided a written response relating to the topic of responsibility. The second most common response had 12 responses (26.1%) relating to vaccine efficacy and efficiency. Nine participants (19.6%) related how personal situations affected their vaccination decision. They discussed those who could not medically receive the vaccine and other personal circumstances. The lowest category was in response to a violation of freedoms. In this category, four participants (8.7%) related to how mandatory vaccinations infringe on the right to choose what goes into one’s body. They explained that getting vaccinated is a right, not a threat used to punish the unvaccinated, disallowing them from participating in some aspects of society as a result of a vaccine mandate. In this same category, one participant (2.2%) highlighted the fact that fully vaccinated individuals can still contract the virus.

Figure 6

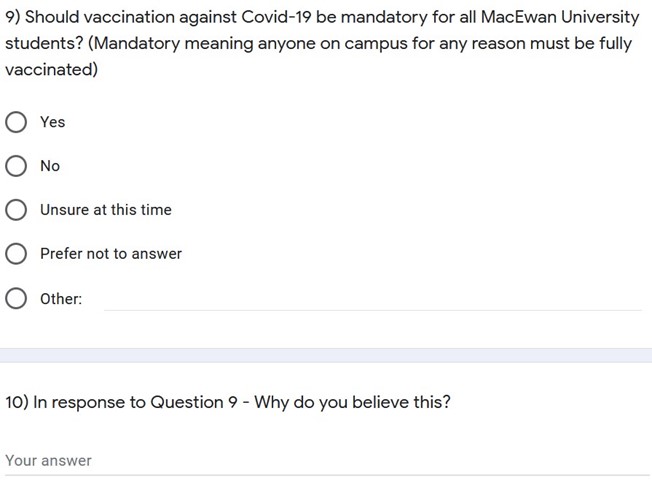

Question 11: Do you believe vaccination is a safe option to fight Covid-19? — 49 responses

Question 11 received responses from all 49 survey participants. The most common answer in this question was ‘Yes,’ with 43 participants (87.8%) agreeing that they believe vaccination is a safe option to fight Covid-19. The second most common response was ‘Unsure,’ with 6 responses (12.2%). No participants chose ‘No’ or ‘Prefer not to answer’ (Figure 6). The overwhelming percentage of those who picked ‘Yes’ most likely provided the written answers relating to responsibility and vaccines being the best defense against Covid-19.

Vaccine Information Sources

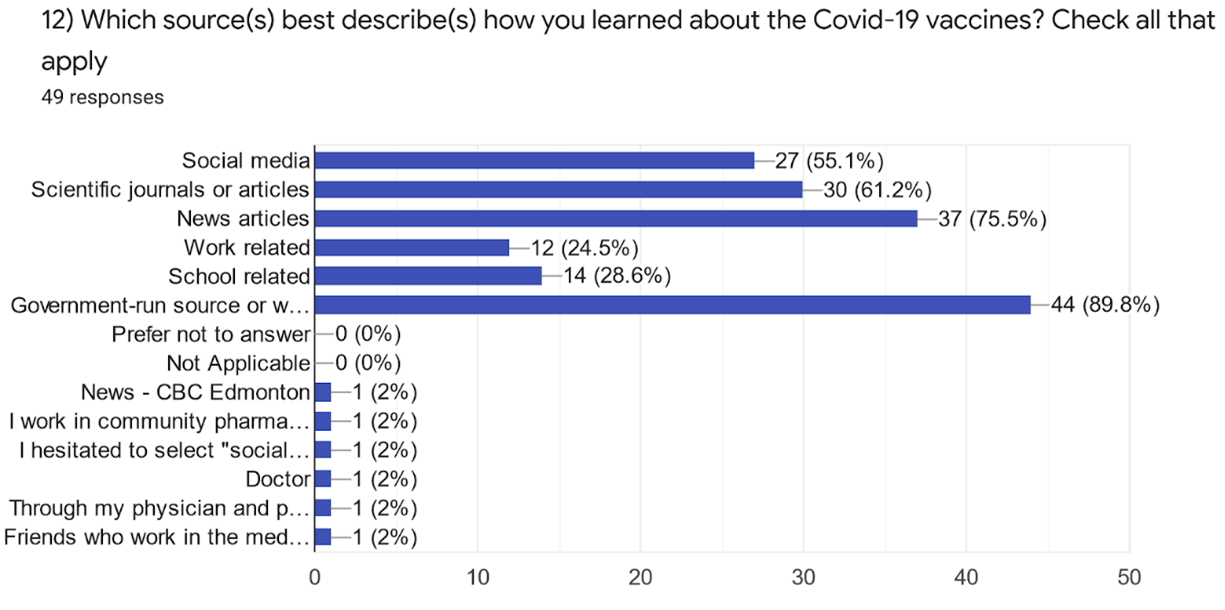

Question 12: Which source(s) best describe(s) how you learned about the Covid-19 vaccines? — 49 responses

Question 12 received a response from all 49 survey participants. The outliers of this question provided their own answers that detailed their sources coming from a personal connection with a medical professional. The most common source of vaccine information was obtained from a government-run source, with 44 participants (89.8%) choosing it as one of their primary sources. The second most common source, with 37 responses (75.5%), was news articles. Most vaccine information the participants saw came from professional sources that created vaccine campaigns and messaging for the public to raise awareness for the Covid-19 vaccine (see Appendix B).

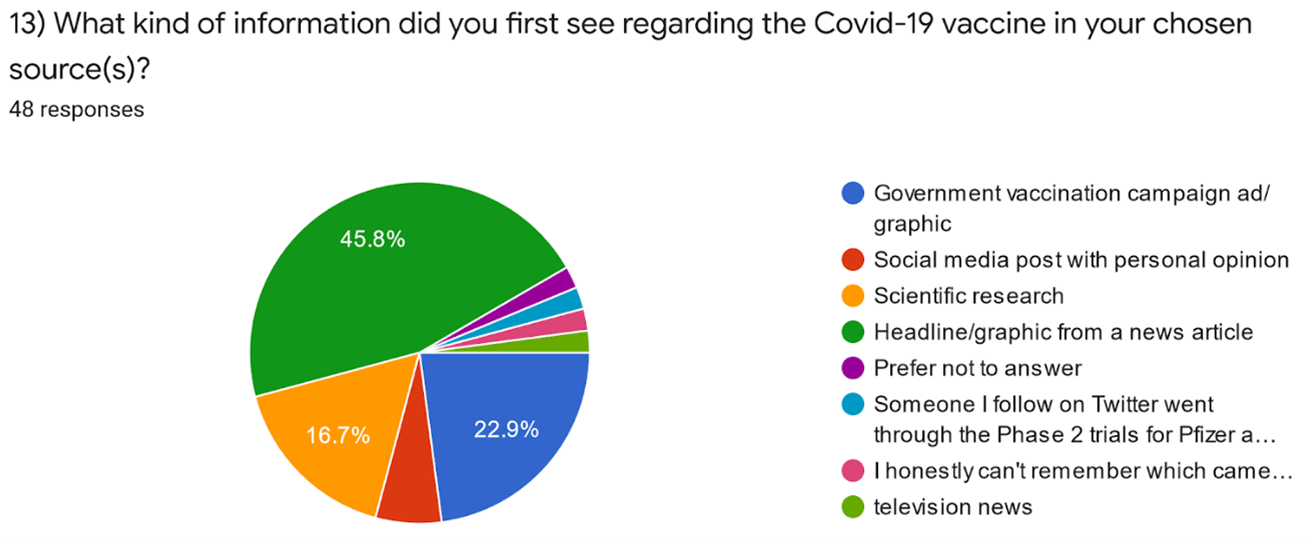

Question 13: What kind of information did you first see regarding the Covid-19 vaccine in your chosen source(s)?— 48 responses

Question 13 received 48 responses, with 22 participants (45.8%) selecting ‘Headline/graphic from a news article as their first source for information regarding the Covid-19 vaccines (see Appendix B). One participant (2%) selected ‘television news’ and one participant (2%) identified a Twitter user documenting their experience trialing the Pfizer vaccine as their primary source of vaccine information. The most prominent response came from the ‘Government vaccination campaign advertisement’ category which received 11 responses (22.9%).

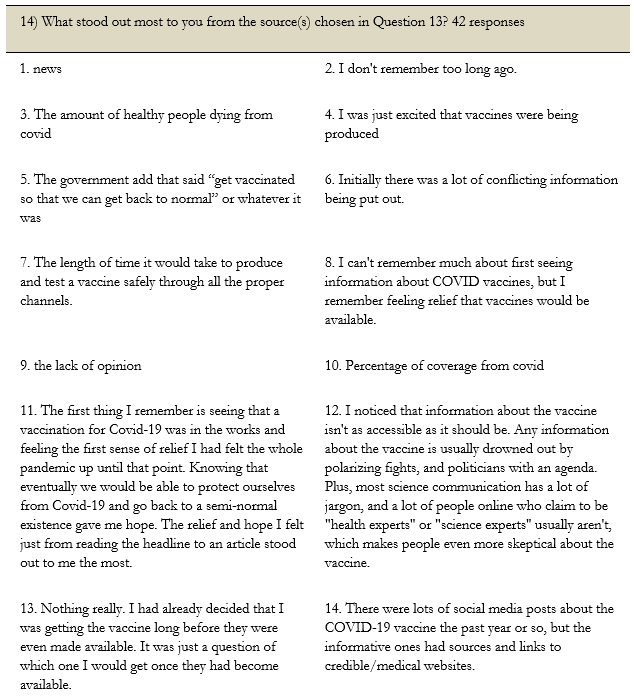

Question 14: What stood out most to you from the source(s) chosen in Question 13?— 42 responses

Question 14 received 42 responses, with five participants (11.9%) not declaring stand-out information from their identified sources of information (see Appendix B). Nine participants (21.4%) commented on the coverage style regarding vaccination information and the least common response was from three participants (7.1%) citing conflicting information or a negative perspective regarding vaccination. Eight participants (19%) cited their relief and predetermined trust in vaccines and five participants (11.9%) identified government rollout and information as stand-out aspects of the information.

Conclusion

This study’s survey was conducted to determine perspectives on mandatory vaccination among the Bachelor of Communication Studies students and alumni at MacEwan University. The data collected is noteworthy not only for the perspectives expressed but also for the reasoning and background information provided alongside the perspectives. How it was analyzed within the study reflects the correlative factors, patterns, and commonalities between the responses provided in the survey (see Appendix B).

Discussion

Memorable and Important Data to the Research Study

The data provided below showed a pertinent connection to the premise of this study and adds to a further understanding of the topic of mandatory vaccination in post-secondary institutions.

Forty-three participants for question 6 identified as two-dose vaccinated at their time of response, with two participants having received a booster shot (Figure 1). These statistics show that 45 participants have taken the steps to fully immunize themselves against Covid-19. Notably, this implies at least 2 of the 6 participants from question 11 who chose ‘Unsure’ for vaccinations being a safe option to fight Covid-19 have received at least two doses of a vaccine. The same number of participants, 43, believe vaccination is a safe option to fight Covid-19.

Sixteen participants for question 8 cited protection of others’ health as their influence for receiving a vaccine. Participants identified ‘protecting family’, ‘protecting immunocompromised’, and the ‘right thing to do for society’ as their reasons for receiving a vaccination (Figure 3). This shows more participants citing an empathy-driven response over an individually-driven response as influential factors for immunizing themselves against the Covid-19 virus (see Appendix B).

Overall, 39 participants from question 9 support mandatory vaccination at MacEwan, with 5 participants emphasizing an account for the medically exempt (Figure 4). Thirty-two of the 46 participants from question 10 identified ‘civic/public responsibility’ and ‘defense against Covid-19’ as factors for their support of mandated vaccines and the inclusion of medical reasons as valid exemptions from vaccination (Figure 5). This data emphasizes an empathy-driven response and reasoning for vaccination.

Nine of 42 responses from question 14 commented on the type of vaccine coverage as the prominent feature of their primary sources. Eight participants cited their relief at having a vaccine for Covid-19 or their predetermined belief in vaccines as prominent factors. As well, seven participants identified the associated statistics and research as prominent features within the information and/or sources they first encountered regarding vaccination and vaccines. Only three participants cited conflicting information or a personally negative response to their initially encountered information/sources as prominent features (see Appendix B). This data emphasizes how similar information can stand out in different ways to different audiences.

Overall, the survey concluded with question 15 showing 40 of 47 participants approving of vaccination in general, with 6 participants viewing vaccination positively but disagreeing with making vaccines mandatory. Notably, one participant negated their response by stating they had expressed their views previously (see Appendix B).

Consistencies and Correlations

The data below depicts correlations between different and similar sets of responses from the survey questions, as well as the consistency of responses throughout the survey period.

A significant consistency was a positive response to mandatory vaccinations and that it is a safe option to fight the Covid-19 virus. The motivating factor of responsibility and keeping everyone healthy was consistent throughout the survey. Data from question two showed that 29 participants were in their third or fourth year of study and question one showed the age range for the participants was commonly 17–25 years (Figure 1). Question 5 reflected how the political preferences remained consistent during the survey period, with the New Democratic Party in the lead with 30 responses. As well, a majority of participants coming from an urban setting with 29 responses remained consistent throughout the survey (Figure 2). Twenty of the written responses to question ten are similar in viewing vaccination as a civic duty and public responsibility. Thirty-two participants also relate to the desire to keep case numbers low and to keep everyone safe (Figure 5). These similarities correlate with the 34 participants from question 9 who believe that mandatory vaccinations should be necessary (Figure 4).

As represented in question 11, 43 participants believed vaccines are safe and effective against Covid-19 (Figure 6). This correlates with the 34 participants for question 10 who believe that mandatory vaccinations should be in place and those who wrote answers about public responsibility and how the vaccine is the best way to keep infection numbers low (Figure 5). The six participants for question 11 who said they are unsure could be the same participants who chose the other options in question nine about getting vaccinated unless they had a medical reason not to (Figure 4). Another correlation to these 6 participants could be the individuals exposed to misinformation online since a majority of participants from question 12 received their vaccine information from social media or news platforms.

Recommendations

Based on the information gathered through this research study, a similar survey could be implemented in various settings to improve understanding regarding the general public’s perspectives on mandatory vaccination. Specifically, the findings from this survey have the potential to benefit other post-secondary institutions and their students, as vaccination perspectives are made clear. The information obtained from this survey may allow post-secondary institutions insight into student population perspectives on returning to in-person education with a vaccine mandate. This study could also be implemented globally to encourage other institutions to consider student perspectives on vaccination before making decisions regarding subsequent semesters. This research may be continued by other student researchers from various universities to allow for more student perspectives on mandatory vaccination. In the future, this study can be changed in length or design as it is applied in different institutions to acquire data from other faculties and departments. Data from this study could also be used in all forms of education if the institution is willing to hear the students’ perspectives on the matter.

Similar research could be applied to the government decision-making process regarding vaccination mandates for the public. This information may alert public health officials and governments on influencing factors, generational patterns, and reasons for hesitancy surrounding the Covid-19 vaccine. The survey could be altered to acquire more detailed information pertaining to the participant’s demographics to emphasize vaccination perspectives, factors, and patterns within a particular population. As a result, government mandates would be fully informed about public perspectives and perceptions around mandatory vaccination. Campaigns, messaging, and research will become more targeted once these patterns and influencing factors are exposed.

The survey could be adjusted to obtain student views on instruction style and how classes should be run during the pandemic at MacEwan University. This survey can be made available to all faculty and staff at the university to obtain a broader understanding of the institution’s perspective on mandating vaccination and the operation of the university. The questions could be changed to accommodate instructors’ perspectives, as well as students, as they are also being exposed to Covid-19 while on campus. This research may be useful for subsequent semesters and for gaining student opinions on how classes should be operated. Surveying the student population and staff regarding exposure to sickness may also affect how the university handles students attending classes on campus with illnesses other than Covid. Overall, the survey could be adjusted to affect how MacEwan University operates its classes and how they handle student and faculty interactions with a vaccine mandate.

References

Anderson, D. (2021, September 15). A reality check on Alberta’s path to the devastating 4th wave of COVID. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/covid-fourth-wave-alberta-reality-check-1.6175 564

Assaly, R. (2021, September 16). How we got here: A timeline of Alberta’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2021/09/16/how-we-got-here-a-timeline-of-albertas-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic.html

Bogart, N., Dunham, J., & Neustaeter, B. (2021, August 13). ‘We are not anti-vaxxers’: Concerns over side-effects, research among main reasons some Canadians are not getting COVID-19 vaccine. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/we-are-not-anti-vaxxers-concerns-over-side-effects-research-among-main-reasons-some-canadians-are-not-getting-covid-19-vaccine-1.5545896

Bowen, R. A.R. (2020). Ethical and organizational considerations for mandatory COVID-19 vaccination of healthcare workers: A clinical laboratorian’s perspective. Clinica Chimica Acta, 510, 421–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2020.08.003

Brüssow, H. (2021). COVID-19: vaccination problems. Environmental Microbiology, 23(6), 2878–2890. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.15549

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, November 4). Workplace vaccination program. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/essentialworker/workplace-vaccination-program.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, November 24). Understanding How COVID-19 Vaccines Work. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/how-they-work.html

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage Publications. https://www.academia.edu/57201640/Creswell_J_W_2014_Research_Design_Qualitative_Quantitative_and_Mixed_Methods_Approaches_4th_ed_Thousand_Oaks_CA_Sage

Deroo, S. S., Pudalov, N. J., & Fu, L. Y. (2020). Planning for a COVID-19 Vaccination Program. JAMA network, 323(24), 2458–2459. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2766370

Dodd, R. H., Pickles, K., Nickel, B., Cvejic, E., Ayre, J., Batcup, C., Bonner, C., Copp, T., Cornell, S., Dakin, T., Isautier, J., & McCaffery, K. J. (2021). Concerns and motivations about COVID-19 vaccination. The Lancet, 21(2), 161–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30926-9

Giubilini, A. (2021). Vaccination ethics. British Medical Bulletin, 137(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa036

Government of Canada. (2020, December 9). Health Canada authorizes first COVID-19 vaccine. Health Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2020/12/health-canada-authorizes-first-covid-19-vaccine0.html

Government of Canada. (2021, November 19). Health Canada authorizes use of Comirnaty (the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine) in children 5 to 11 year of age. Health Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2021/11/health-canada-authorizes-use-of-comirnaty-the-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-in-children-5-to-11-years-of-age.html

Gur-Arie, R., Jamrozik, E., & Kingori, P. (2021). No jab, no job? Ethical issues in mandatory covid-19 vaccination of healthcare personnel. BMJ Global Health, 6(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004877

Hartshorn, B. (2021, October 8). Vaccine mandates and proof of vaccination. Alberta Human Right Commission. https://albertahumanrights.ab.ca/covid/Pages/vaccines.aspx

Government of Canada. (2021, September). Approved COVID-19 Vaccines. Health Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/covid19-industry/drugs-vaccines-treatments/vaccines.html

Hu, T., Wang, S., Luo, W., Zhang, M., Huang, X., Yan, Y., Liu, R., Ly, K., Kacker, V., She, B., & Li, Z. (2021). Revealing Public Opinion Towards COVID-19 Vaccines With Twitter Data in the United States: Spatiotemporal Perspective. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(9). https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.02.21258233

Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2020). What is coronavirus? Johns Hopkins Medicine.

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus

Johnson, R. B., Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Turner, L. A. (2007). Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224

Katella, K. (2021, September 24). Comparing the COVID-19 Vaccines: How are they different?. Yale Medicine. https://www.yalemedicine.org/news/covid-19-vaccine-comparison

Laurier, J. B., Lapointe, V., Kaufer, D. J., & Aronovitch, S. (2021, August 20). Mandatory vaccine policy in the workplace: An overview for Canadian employers. BLG. https://www.blg.com/en/insights/2021/08/mandatory-vaccine-policy-in-the-workplace-an-overview-for-canadian-employers

Le, T. T., Andreadakis, Z., Kumar, A., Román, R. G., Tollefsen, S., Saville, M., & Mayhew, S. (2020). The COVID-19 vaccine development landscape. PubMed, 19(5), 305–306. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41573-020-00073-5

Liu, S. (2021, April 26). How long does it take for the COVID-19 vaccines to become effective?. CTVNews. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/how-long-does-it-take-for-the-covid-19-vaccines-to-become-effective-1.5402892

MacEwan University. (n.d.). Bachelor of communication studies. Bachelor of Communication Studies – MacEwan University. Retrieved October 6, 2021, from https://www.macewan.ca/academics/programs/bachelor-of-communication-studies/

National Advisory Committee on Immunization. (2021, October 29). An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): Interim guidance on booster COVID-19 vaccine doses in Canada. Public Health Agency of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/guidance-booster-covid-19-vaccine-doses/guidance-booster-covid-19-vaccine-doses.pdf

Reiss, D., & DiPaolo, J. (2021). Covid-19 Vaccine Mandates for University Students. SSRN, 1–74. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3874159

Shi, B., Qiu, H., Niu, W., Ren, Y., Ding, H., & Chen, D. (2017). Voluntary Vaccination through Self-organizing Behaviors on Locally-mixed Social Networks. Scientific reports, 7(1), 2665. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02967-8

Slack, J. (2021, October 25). Alberta opposition question UCP government’s pandemic response in first day of fall sitting. CityNews Calgary. https://calgary.citynews.ca/2021/10/25/alberta-fall-sitting-covid/

Sprengholz, P., Betsch, C., & Böhm, R. (2021). Reactance revisited: Consequences of mandatory and scarce vaccination in the case of COVID- 19. International Association of Applied Psychology, 13, 986–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12285

Vasquez-Peddie, A. & Neustaeter, B. COVID-19 vaccine booster eligibility by province and territory in Canada. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/covid-19-vaccine-booster-eligibility-by-province-and-territory-in-canada-1.5626554

Wesley, J., Hyshka, E., Snagovsky, F., Carlson, N., Downe, P., & Mou, H. (2020, October 28). The politics of Covid-19 in Alberta. Common Ground Politics. https://www.commongroundpolitics.ca/the-politics-of-covid19-in-alberta

Wesley, J. & Snagovsky, F. (2021, March 18). Viewpoint Alberta: Major shifts in vote intentions. Common Ground Politics. https://www.commongroundpolitics.ca/viewpoint-alberta-major-shifts-in-vote-intentions

World Health Organization. (2020). Coronavirus. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus

Appendix A

Survey

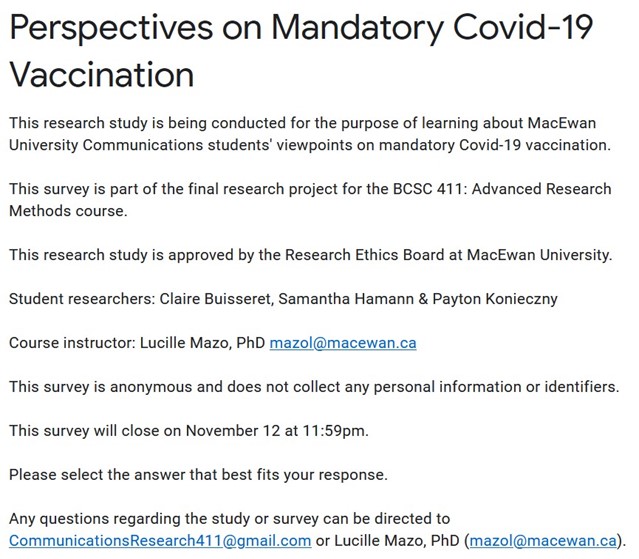

Figure A1. Survey instructions and explanation.

Figure A2. Question that asks participants to consent to participate in survey.

Figure A3. First demographics question regarding age range and second demographics question regarding year of study.

Figure A4. Third demographics question regarding major and fourth demographics question regarding location.

Figure A5. Fifth demographics question regarding political preferences.

Figure A6. Sixth survey question regarding vaccination status.

Figure A7. Seventh survey question regarding vaccination type and eighth survey question regarding vaccination influences.

Figure A8. Ninth survey question regarding mandatory vaccination and tenth survey question which allows for expansion.

Figure A9. Eleventh survey question regarding vaccine safety.

Figure A10. Twelfth survey question regarding vaccine information sources.

Figure A11. Thirteenth survey question regarding vaccine information sources and fourteenth survey question which allows for expansion.

Figure A12. Fifteenth survey question regarding vaccination views.

Appendix B

Raw Survey Response Results

Figure B1. Question one results.

Figure B2. Question two results.

Figure B3. Question three results.

Figure B4. Question four results.

Figure B5. Question five results.

Figure B6. Question six results.

Figure B7. Question seven results.

Figure B8. Question nine responses.

Figure B9. Question 11 responses.

Figure B10. Question 12 responses.

Figure B11. Question 13 responses.

Table B4. Question 15 written responses.