Filling Time: The Connection Between Hobbies, Mental Health, and University Students During the Covid-19 Pandemic

Josh Hui, Jett Niemeyer

Abstract

Covid-19 lockdowns have significantly changed everyone’s lives, especially the lives of university students. A lack of in-person social interaction due to hybrid and online classes has led to an increase in isolation and loneliness. One way that people might cope with the psychological challenges of Covid-19 restrictions is through participating in hobbies. This study discovered that hobbies positively impacted the mental health of university students during the Covid-19 pandemic. The hypothesis was that hobbies would be beneficial for university students’ mental health, so long as the time spent participating was reasonably monitored. By defining four types of hobbies—electronic, physical, logical, and artistic—this research provided insights into the connection between people’s favourite hobbies and their mental health. The research was conducted through a Google Forms survey online over a two-week period. Fifteen students at MacEwan University aged 18–46 answered a 16-question survey combinining open-ended and closed-ended questions. The questions fit into three main categories: demographic, lifestyle, and mental health. Demographic questions asked participants specific information about themselves and their academic situations, lifestyle questions look at participants’ day-to-day activities, and mental health questions assessed the emotional response to an individual’s lifestyle. The research concluded that all participants’ hobbies brought them joy. Amongst the hobby types, physical, logical, and electronic hobbies (in moderation) were most associated with joy. On the other hand, artistic and electronic hobbies were more likely to bring stress. Finally, the majority of participants reported that their number one source of hobby-related joy came from escaping stress and social connections. The number one source of hobby-related stress resulted from perfectionism.

Keywords: hobbies, mental health, university students, Covid-19, stress, joy

Introduction

Statement of Purpose

The hypothesis of this research was to determine whether hobbies positively impacted university students’ mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic. This research applied the definition of hobby from Pressman et al.’s (2009) definition of “leisure activity” as “pleasurable activities that individuals engage in voluntarily when they are free from the demands of work or other responsibilities… includ[ing]… sports, socializing, or spending time in nature” (p. 1). Examining categories of joy and stress (Whitehead & Torossian, 2020) helped to determine the reasons that individuals saw a positive or negative mental health outcome during the Covid-19 pandemic. Research showed that certain hobbies may be more beneficial than others. Hobbies that are actively involved, like soccer, have helped maintain an overall healthier lifestyle (Ng et al., 2020). However, some more popular hobbies may have a negative effect on university students’ mental health if left unregulated (Twenge & Farley, 2020; Ali et al., 2021). Social media and excessive internet use, for example, could lead to a negative outlook on life due to factors like lack of sleep, poor self-esteem, and social comparison (Twenge & Farley, 2020).

This current study defined four main types of hobbies: physical, electronic, logical, and artistic. These hobby types determined which ones were more beneficial for maintaining an individual’s mental health than others. This study also examined the relationship between the physical act of hobbies themselves and the subcultures that allow for a deeper connection to an individual’s hobby. For example, if one enjoys cooking, they may also enjoy watching cooking shows or looking for recipes through blogs.

Research in this study was performed through an online survey with three categories of questions: demographic, lifestyle, and mental health. These categories presented an overall picture of students’ daily activities and the general circumstances that influence their mental well-being.

Research Problem

With Covid-19 restrictions, many individuals have experienced increased isolation and limited socialization which may lead to mental health issues such as depression. As a result, many individuals may turn to their favourite hobbies to help cope with these feelings. But are these hobbies adding to or solving the problem? Government restrictions during the pandemic, including replacing physical interaction with virtual interaction, have “led to a negative impact on the mental health of students” (Ali et al., 2021, p. 2).

The main research question for this study: How have hobbies impacted the mental health of university students during the Covid-19 pandemic?

Sub-questions:

- What motivated one’s participation in their chosen hobby/hobbies?

- What are the most popular types of hobbies?

- Did these hobbies contribute negatively or positively to students’ mental health?

- Does participating in a hobby/hobbies mean also engaging in the subculture(s) associated with one’s chosen activity?

Significance of the Study

As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, university students faced the unique challenge of having to perform their academic studies either exclusively online or in a hybrid form of in-person/online learning. Therefore, they required more self-discipline to keep up with their studies and likely spent more time at home than in years prior. Hobbies can have mental health benefits, but the increased time spent at home caused by the pandemic may turn these hobbies into distractions and therefore cause more stress, especially if left unmonitored (Ali et al., 2021; Twenge & Farley, 2020). The types of hobbies within this current study—electronic, physical, logical, and artistic—were unique to this research. Defining these four types helped to clarify the main activities people enjoy and how those activities affected their mental health. This study determines which hobbies were most beneficial to people’s mental health, as well as which ones were more popular during the pandemic. Results provided objective and subjective reasoning for the causation of stress, explained the value of participants’ hobbies, and described how effective hobbies were at coping with mental health issues.

Limitations

The limitations of this research consisted of the time period and demographic selected. University students varied significantly in age but most of the data came from those aged 18-46 who have hobbies that differed from others much older or younger. Only the hobbies of the participants of this study were included; therefore, there were likely other hobbies—specifically from different age groups—that were not be studied. With technological advancements, there may be new hobbies discovered in the future that will not be considered presently. The timeline for the survey was limited to late 2021, nearing the possible end of Alberta’s fourth wave of Covid-19. The survey asked participants to answer questions about their mental health over the course of the pandemic. Conducting a similar survey in the middle of a new wave or at the end of one may have led to much different answers from participants. Additionally, it is difficult to measure the mental health of students based on only survey questions. The survey did not ask questions that were too personal such as any past medical history of students that may have more clearly determined any mental health issue. The questions of the survey required long-form answers, enabling participants to provide as much detail as they felt necessary. Given that some questions were subjective, some answers were too short to gather accurate data.

Definitions of Terms

Artistic Hobbies

Conforming to the standards of art; satisfying aesthetic requirements (Dictionary.com, n.d.).

Hobbies that require participants to be creative (e.g. painting, cooking, playing music) (Niemeyer & Hui, personal communication, 2021).

Electronic Hobbies

Of, relating to, or controlled by computers or computerized systems (Dictionary.com, n.d.).

Hobbies that require technological devices in order to participate. (e.g. videogames, television watching, social media) (Niemeyer & Hui, personal communication, 2021).

Logical Hobbies

Reasoning in accordance with the principles of logic, as a person or the mind (Dictionary.com, n.d.).

Hobbies that require some form of logical stimulation to participate (e.g. Puzzles, reading, writing, learning a language) (Niemeyer & Hui, personal communication, 2021).

Physical Hobbies

Of or relating to the body (Dictionary.com, n.d.).

Any hobby that involves physical activity (e.g. sports, running or walking, bodybuilding) (Niemeyer & Hui, personal communication, 2021).

Summary

The purpose of this current study was to determine how hobbies have impacted the mental health of university students during the Covid-19 pandemic. The researchers hypothesized that hobbies would be beneficial for university students’ mental health, so long as the time spent participating is reasonably monitored. Research questions determined what activities were most popular during the pandemic out of the four types of hobbies, how these hobbies affect participants’ mental health, and which ones were more beneficial than others. The limitations of this study mostly pertained to the time period and demographic of participants. Hobbies varied between age groups so certain demographics might enjoy hobbies that others might not. Research focused on university students because of the unique mental health challenges of online/hybrid learning during the pandemic. The time frame selected may not be as much of a stressor on students since Covid-19 has become more manageable in comparison to when it initially started.

Review of the Literature

Introduction

This research surveyed six different sources that examined the Covid-19 pandemic, screen-time hobbies, habits, and the effects of activities on students’ mental health. These sources provide a framework for building survey questions, analyzing the mental health effects of Covid-19, and comparing some hobbies’ effects on mental health regardless of Covid-19.

Not All Screen Time is Equal

It is almost common knowledge to conclude that the pandemic has led to an increased usage of screen time among adolescents and young adults. More time spent at home likely has meant that distractions such as television, gaming, the internet, and social media have become more enticing ways to pass time. However, despite their popularity, these hobbies may have led to an increase in mental health issues if left unregulated (Twenge & Farley, 2020). Twenge and Farley (2020) studied the mental health effects of screen time on 13-15-year-old boys and girls in the United Kingdom (UK). Social media and internet use, in particular, had the most negative impact on adolescent girls. The research added that the longer adolescent girls spent on social media or the internet, the more they experienced “self-harm behaviors, depressive symptoms, low life satisfaction, and low self-esteem” (p. 207).

The study determined that social media and internet use were more harmful to an individual’s mental health than video games or TV watching (Twenge & Farley, 2020). However, gaming and television watching were less likely to instigate social comparison because they do not have as many elements of anonymity, permanent messaging, and social contact. The largest statistic demonstrated that 36.4% of girls felt they had lower self-esteem when using the internet for more than five hours and 36.2% felt the same way using social media for similar amounts of time. For boys, the data concluded that screen time was less likely to cause depressive symptoms; 16.1% felt a lower life satisfaction when consuming more than five hours of social media daily (Twenge & Farley, 2020). Comparatively, the negative effects of screen time were more prominent in girls, even if they spent less than or equal to one hour each day on the platform. Even when spending a small amount of time using a screen, it was far more likely that girls saw more negative effects on their mental health than boys. It showed that certain groups of individuals may be more vulnerable to a negative mental health outcome when overconsuming certain electronic hobbies.

Activity Participation and Perceived Health Status in Patients with Severe Mental Illness

Ng et al. (2020) examined patients who suffered from a form of severe mental illness (SMI), such as psychosis, depression, and schizophrenia, and the connections between somatic (physical) and mental wellbeing along with how certain activities affect them (Ng et al., 2020). Three activity categories were defined by the research: basic-care, interest-based (watching television, doing simple craftwork, reading newspapers, and outdoor sports activities such as soccer, badminton, and Tai Chi), and role-based activities or life goal-oriented activities (domestic work training, work-related training selected by the patient and case therapist) that the participants could join in or decline at any time. The research observed 84 patients between the ages of 16 and 63 throughout their hospital stays and measured their somatic and mental health before and after their stay. The results found that “physical activities result in decreased illness symptoms in 57.4% of patients, with only a few reported negative effects” (p. 99). Overall, the study concluded that “participating in activities of patients’ own choice and interests is positively associated with patients’ psychiatric and somatic health and subjective wellbeing” (p. 99). The positive effects of these activities could be seen up to a month after release from the hospital and consistent participation could be a useful nonpharmacological treatment for SMI patients. If patients participated in these activities for longer periods, the results would be more beneficial to their health (Ng et al., 2020). This study indicated that interest-based activities were beneficial for mental and physical health, even in significant cases of mental health challenges.

Older Adults’ Experience of the Covid-19 Pandemic

Whitehead and Torossian (2020) used an online survey to disclose the most common sources of stress and joy during the Covid-19 pandemic. It examined the demographic of 825 “older adults” (p. 36) aged 60 and older in the United States and asked them questions relating to 20 sources of stress and 21 sources of joy they felt during the pandemic. The 20 sources of stress included the following:

Restrictions/confinement, concern for others, isolation/loneliness, unknown future, shopping, government, news, nothing, house stresses, adapting to change, work, economy/finances, lack of motivation/focus, getting/preventing the virus, mental health/focus, boredom, health (not virus related), other people, unable to help, weather, and miscellaneous. (Whitehead & Torossian, 2020, p. 40)

The 21 sources of joy were “family/friends, digital interaction, hobbies, pets, spouse/partner, faith, nature, peace of mind, exercise/self-care, grandkids, food/drink, helping, productivity, extra time, work, neighbors, nothing, miscellaneous, humor, and government” (p. 40). The top three sources of joy were family/friends (31.6%), digital contact (21.9%), and hobbies (19.3%), and the top three sources of stress were confinement (13.2%), concern for others, (12.4%), and isolation/loneliness (11.8%) (Whitehead & Torossian, 2020).

Their study stated that hobbies were a reliable source of joy among even older demographics, and also provided a template for the causation of stress during the pandemic. However, the sources of stress that had a significant negative effect on mental health were concerns for others, the unknown future, and contracting the virus. The sources of joy that had the most positive mental health outcomes consisted of faith (11.5%), nature (11%), and exercise/self-care (>10%) (Whitehead & Torossian, 2020). The sources of joy that led to more positive well-being were not even in the top three among participants. Unless hobbies involve a combination of exercise, faith, and nature, it is likely to assume that some hobbies may be beneficial for mental health, but only to a certain extent. Their study indicated that hobbies can be a source of de-stress for adults but that it is also essential to maintain other sources of happiness, such as exercise, for the best mental health outcomes. The study lists several stresses and joys that people experience specifically during the pandemic. Whitehead & Torossian (2020) provided a framework for comparison to this current study.

Association of Enjoyable Leisure Activities With Psychological and Physical Well-Being

Pressman et al. (2009) researched the connection between hobbies and mental and physical wellbeing. Hobbies, called leisure activities in the study, were defined as “pleasurable activities that individuals engage in voluntarily when they are free from the demands of work or other responsibilities… includ[ing] hobbies, sports, socializing, or spending time in nature” (p. 2). Adult participants reported how they felt after participating in 10 different activities by measuring their “resting blood pressure, cortisol (over two days), body mass index, waist circumference, and perceived physiological function” (p. 1). The activities included “spending quiet time alone; spending time unwinding; visiting others; eating with others; doing fun things with others; club, fellowship, and religious group participation; vacationing; communing with nature; sports; and hobbies” (p. 4). The importance of this study was to focus on the impact positive behaviors have on an individual’s overall health. Participants reported that “engaging in multiple types of leisure activities plays a role in buffering the negative psychological impact of stress” (p. 9). Pressman et al.’s (2009) study provided a link between hobbies and improved overall wellbeing. It also outlined the benefits of an individual engaging in multiple hobbies to maintain a well-balanced lifestyle.

Effects of Covid-19 Pandemic and Lockdown on Lifestyle and Mental Health of Students

Ali et al.’s (2021) study examined how Covid-19 restrictions around the world impacted the mental health of university students. Ali et al. researched how pandemic lockdowns impacted the health and lifestyle of students in Pakistan. Through a series of close-ended survey questions, participants provided information about their demographic, perception of time during the pandemic, sleep patterns, digital media usage, and mental health. Ali et al. (2021) discovered that for most participants, “getting through quarantine would have been more difficult if they did not have any electronic gadgets” (p. 1). They also uncovered an increase in social media usage during the pandemic which resulted in worse sleep habits and worse student mental health. If students went to sleep later, they would not get high-quality sleep which could cause tiredness and a lack of motivation. It is possible that participating in hobbies requiring physical activity, such as sports, could counteract the impacts of extended social media usage. The study recommends “promoting better sleep routines, minimizing the use of digital media, and encouragement of students to take up more hobbies could collectively improve the health and mood of students in self-quarantine” (p. 1). Ali et al.’s (2021) research contributed to this current study by establishing that the need for rest helps maintain an individual’s mental health. Their study also indicated that an increased use of social media and electronic devices during the Covid-19 pandemic had negative impacts on students.

Psychology of Habit

Wood and Rünger (2016) examined the neuroscience behind habit formation by providing three ways that habits help people pursue their goals. First and foremost, the research explained that habits are a series of repeated actions. When people choose a hobby, they respond to a set of circumstances by picking an activity they can participate in consistently. In this current study, people might report trying to combat the isolation of online classes by scheduling Facetime calls with friends to foster connection and bring happiness. Another reason for choosing a hobby is the connection to reaching a goal. Chasing after a goal can motivate someone to repeat a hobby. If someone is trying to learn a language, they will practice repeatedly to become fluent. Additionally, if an individual chooses to run as a hobby, they must train consistently before running a marathon. Finally, people make an intentional choice when selecting a hobby (Wood and Rünger, 2016). In other words, habits are formed when people repeatedly make the same decisions for the same reasons. A worldwide pandemic provided people with more time to make those decisions and choose hobbies for different reasons. Wood and Rünger’s (2016) study contributed to this current study by exploring the motivation behind partaking in certain hobbies and what impacts those hobbies can have on participants’ mental health.

Contribution This Study Will Make to the Literature

A key contribution this current study made to the discourse of hobbies and mental health was to provide definitions for the four main types of hobbies: electronic, physical, logical, and artistic. Hobby types were designed to broadly include a wide variety of potential activities within the types. For example, physical hobbies could refer to basketball, soccer, hockey, rock climbing, or running. Therefore, results obtained that measure the connection between mental health and physical hobbies could apply to those who participate in the activities listed above. Defining these four types provided key information about the lifestyles of the participants and how these hobbies impacted their overall wellbeing. While the studies in the literature review provided frameworks and definitions for this research, the data gathered captures more specific results of a particular demographic during the Covid-19 pandemic. This research allowed for a clearer connection between hobby participation and mental health. Finally, this current study included more hobbies than other studies within the literature review. While other studies may examine the connection between one specific hobby, such as social media and mental health, this study aimed to provide a more well-rounded analysis between multiple hobbies and their mental health impacts. Furthermore, the connection between all the hobbies in this study and mental health can be compared with each other to determine which hobby best copes with stress.

Review of the Problem

This research examined how Covid-19 has changed the way students interact with their hobbies. The pandemic has led to many avenues of stress ranging from a lack of social contact to concern for the future (Whitehead & Torossian, 2020). With the added stress caused by government restrictions and increased time spent at home, these hobbies could be relied upon more to help individuals manage their problems. Certain activities, such as screen-based hobbies, have proven to decrease self-esteem, life satisfaction, cause depressive symptoms, and in some cases, self-harm, when unregulated (Twenge & Farley, 2020). Physical activities, such as soccer, proved to be beneficial for the physical and mental health of patients with severe mental illness (Ng et al., 2020). It is clear that to ensure positive mental health, individuals need to maintain a balance of multiple hobbies as well as a consistent sleep pattern (Ali et al., 2021; Pressman et al., 2009). University students will likely not have the time to dedicate themselves to many hobbies and may rely on just a few to keep life balanced. Ideally, an individual should have at least one activity they enjoy that fits under all four types of hobbies to keep them active, relaxed, and mentally stimulated.

Methodology

Research Methodology

Research performed in this current study used a mixed methods survey analysis. Creswell and Creswell (2018) described mixed methods analysis as the following:

An approach to inquiry that combines or associates both qualitative and quantitative forms. It involves philosophical assumptions, the use of qualitative and quantitative approaches, and the mixing of both approaches in a study. Thus, it is more than simply collecting and analyzing both kinds of data; it also involves the use of both approaches in tandem so that the overall strength of a study is greater than either qualitative or quantitative research. (p. 51)

Design

This current study used an online survey consisting of closed-ended and open-ended questions. The demographic is 18-46-year-old university students at MacEwan University who were balancing the demands of school with the physical and mental challenges of Covid-19 restrictions. Participants anonymously answered questions about the hobbies they participate in during their spare time and reported the effects these hobbies have on their mental health. For some students, that hobby may involve physical activity, like working out or playing a sport. Some may participate in more logical activities, such as puzzles or reading. Other students may enjoy artistic activities, such as painting or playing the guitar. Finally, gaming, social media, or watching TV series are all popular outlets used to pass time.

Quantitative, closed-ended questions provided insight into the lifestyles of the participants, including what their course load was like, what hobbies they enjoy, and their overall mental wellbeing. Qualitative, open-ended questions support the quantitative information and give participants the chance to provide their own accounts of their hobbies and stressors. The research aimed to discover which hobbies most positively impact the mental health of university students while they learn virtually during Covid-19.

The design of this research influenced by three main studies (Twenge & Farley, 2020; Ali et al., 2021; Whitehead & Torossian, 2020) which provided critical theoretical underpinnings for this current study’s research. First, extended usage of social media has been proven to have a negative impact on the mental health of younger demographics, including adolescents and university students (Twenge & Farley, 2020; Ali et al., 2021). The research examined how many students at MacEwan University use social media as an outlet and whether the connection with mental health is consistent with the two studies already listed. Second, sleep habits affected an individual’s mental health (Ali et al., 2021). Additionally, establishing categories for the joy and stress people are experiencing during Covid-19 (Whitehead & Torossian, 2020) helped specify the research being conducted. This current research study connected the stress categories (see Table 4) that people described with their hobbies to determine whether their chosen activities caused them more or less stress. Also, the joy categories (see Table 4) were used to describe some of the emotions people felt after participating in their hobby (or hobbies) of choice.

Sample

The main sample population for this research was 18-46-year-old university students at MacEwan University. Students may have different programs, schedules, and workloads which could result in different levels of stress. Students have busy lifestyles without much free time; therefore, finding hobbies to help destress or escape from the busy schedule is important to maintaining a work-life balance. The hobbies that students engaged in generally fell into the four types defined in this research: electronic, physical, logical, and artistic. Either way, how students chose hobbies, what hobbies they chose, and how that choice impacted them were the main areas of study in this research.

Instrument(s) Being Used in the Study

The research performed in this current study was through a 16-question Google Forms survey. Of those 16 questions, 12 were close-ended and four were open-ended. The Google Forms survey link was posted on Blackboard and emailed to students in the Bachelor of Communication Studies program at MacEwan University. Participants had two weeks to complete the survey from October 21 to November 4, 2021. The main trends this research uncovered included the most popular hobbies amongst university students, what motivated them to choose those hobbies, and what impact those hobbies had on their mental health.

Procedures

Data Collection

The 16-question Google Forms survey consisted of open-ended and closed-ended questions. The closed-ended questions were answered in a multiple-choice format with participants choosing options that best applied to their lifestyle. The open-ended questions provided context to the quantitative data obtained by adding more detail to why participants chose certain hobbies and how it made them feel. The study was available for MacEwan students to fill out through an emailed link.

Data Analysis

The data obtained were divided into three main categories: demographic, lifestyle, and mental health. Demographic information provided more context about the participants themselves, including their age, course load, and program. Lifestyle data described what kind of life participants led, including what hobbies they enjoyed and what their sleep habits were. Finally, mental health questions asked how students viewed their mental health, what they were stressed about, and how their hobbies impacted them. The demographic information likely influenced the participant’s lifestyle which also impacted their mental health. The analysis process involved reviewing the information collected and providing conclusions based on the trends observed in the research.

Summary

The research performed in this current study utilized a mixed-methods 16-question online anonymous survey. The survey conducted through Google Forms gathered qualitative and quantitative data about the motivated choices university students make to participate in certain hobbies. More specifically, this study defined four types of hobbies: electronic, physical, logical, and artistic. The main question this research aimed to answer was whether these hobbies were sources of joy or stress for students and how these emotional responses impacted their mental health. Data was gathered into three categories: demographic, lifestyle, and mental health. Each category impacted the other, resulting in a cohesive analysis. This study revealed which hobbies were most popular and how those hobbies impacted the mental health of the participants.

Results

Introduction to the Data Gathering Process

This current study used a mixed-methods online anonymous survey through Google Forms to gather the results. The 16-question online survey was posted for two weeks between the dates of October 27 to November 10, 2021. The results of the survey were monitored daily, and all applicable data was collected into a spreadsheet until completion. An important element of the data gathering process is providing people with the opportunity to include their own voice in the survey by utilizing open-ended questions. For example, when asking people about some of the joys they experience when participating in their hobby, the questions provided several options that people might identify with. However, there was no way that every single joy could have been listed; therefore, using an “other” option allowed people to fill in the blank if one of the joys they experienced through their hobby was not listed as a potential answer.

This research considered the quality of the long-answer questions. Take question eight, for example. If someone answered question eight, which asked participants to describe their relationship with their hobby/hobbies, with one word, like “good,” or with minimum effort, it would not provide much detail into that participant’s lifestyle. When participants shared more detail in the open-ended questions, it provided a clearer picture of their overall lifestyle and the connection between their hobbies and mental health. Examining the different hobby types throughout the research process helped to determine which type of hobby is most likely to cause stress or joy.

Description of the Instrument(s)

The research data was gathered through a 16-question Google Forms survey. Of those 16 questions, 12 were close-ended and four were open-ended. The Google Forms survey link was posted on Blackboard and emailed to students in the Bachelor of Communication Studies program at MacEwan University. Survey results were monitored daily and inserted into a Google Sheets document to track the responses. This research sought to uncover which hobbies were most popular amongst university students, the relationships that students had with their hobbies, and what impact those hobbies had on mental health.

The questions were divided into three categories: demographic, lifestyle, and mental health. Demographic questions inquired about the participants’ age, course load, and time spent doing schoolwork. These questions provided foundational knowledge to the research by giving a general framework of students’ daily workloads. Lifestyle questions focused on the overall balance between schoolwork and hobbies outside of class. Participants answered questions about what hobbies they enjoyed, their relationship with those hobbies, and their connection to the hobby’s subculture(s). Finally, mental health questions helped determine individuals’ joys and stresses, how they felt about their hobbies, and overall life satisfaction. Mental health questions were designed to provide more emotional responses in comparison to the other categories of questions.

Summary of Data

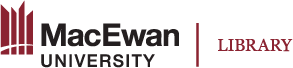

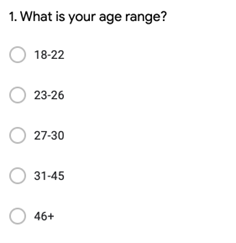

Figure 1

Question 1: What is your age range?

(Answered by 15 participants)

Of the students questioned in the survey, 66.7% were between the ages of

18–22 (10 participants). Additionally, 13.3% (two participants) were in the age range of 31–45.

The age ranges of 23–26, 27–30, and 45+ each represented 6.7% (one participant) of total responses. Based on these statistics, the majority of students surveyed were in the 18–22 age range with the second-highest majority being between 31–45.

Figure 2

Question 2: How many courses do you take in an average semester?

(Answered by 15 participants)

Most of the students surveyed reported carrying close to a full course load. Out of 15 participants, just over 93% (14 participants) said they took either four or five courses in an average semester. Those two options were tied for the most popular answer with 46.7% each (seven participants). One outlier in the data was one student who responded that they take three courses in an average semester.

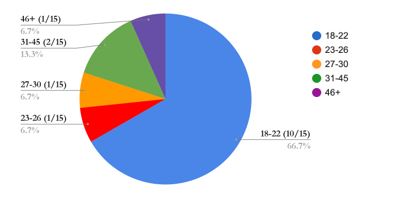

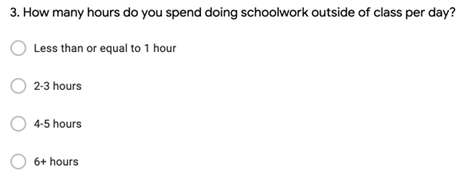

Figure 3

Question 3: How many hours do you spend doing schoolwork outside of class per day?

Question 5: How many hours per day do you spend participating in your hobby/hobbies?

(Answered by 15 participants)

The data above compared the amount of time students spent on schoolwork to participating in hobbies. The most popular response to question three indicated that seven participants spent between four and five hours a day doing schoolwork. Five participants reported spending between two and three hours on schoolwork per day. Only two participants reported spending more than six hours a day doing schoolwork. Finally, just one participant mentioned spending less than or equal to one hour per day doing schoolwork.

In comparison to the amount of time spent working on school assignments or projects, many students reported spending significantly less time enjoying their hobbies. Question three established that seven participants spend four to five hours per day on schoolwork, and the same percentage reported that they spend less than or equal to one hour participating in their hobbies. Additionally, five participants reported spending two to three hours on their hobby/hobbies, while only three participants said they spend four to five hours per day enjoying their hobby/hobbies.

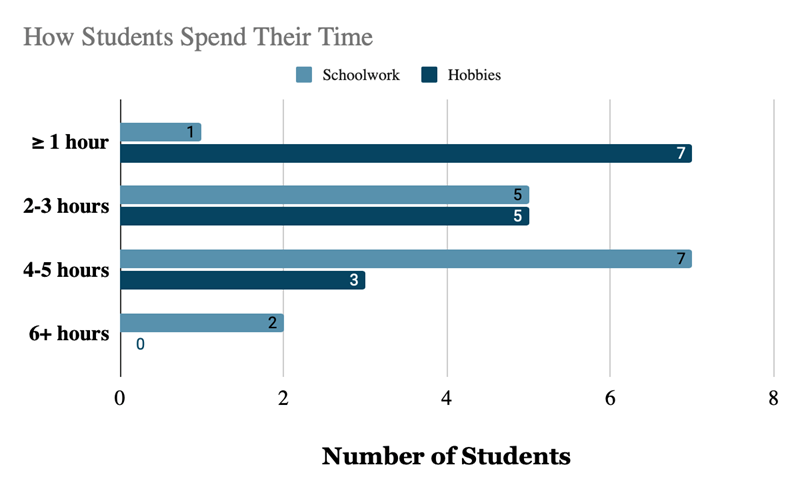

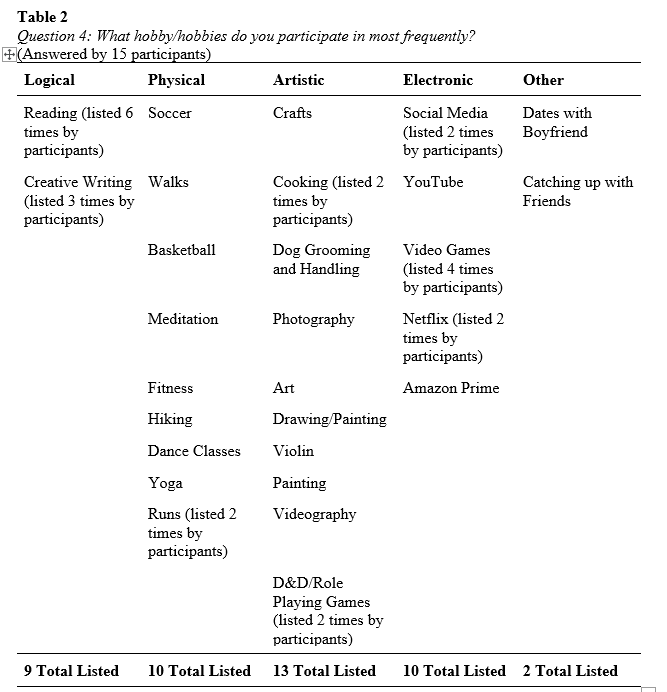

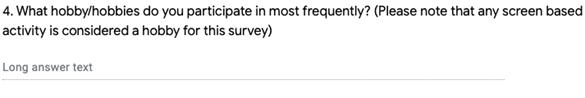

Figure 4

Question 4: What hobby/hobbies do you participate in most frequently?

(Answered by 15 participants)

Question four was open-ended to provide participants the opportunity to list the hobby/hobbies they participate in most often. Therefore, some participants listed more than one hobby. The hobbies listed were classified into the four main hobby types with an additional ‘other’ hobby type (see Table 2). Among the four types of hobbies, the largest number of activities fit under the artistic type with 13 hobbies. The electronic and physical hobby types were tied for second with 10 hobbies each. Lastly, the logical type had the least amount of hobbies mentioned with a total of nine. In terms of the specific hobbies listed, the most popular hobby among the students was reading, which was listed six times. Video games came in a close second with four mentions.

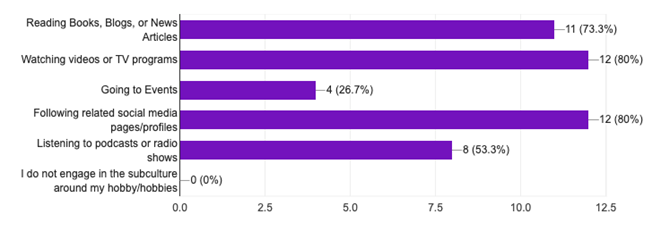

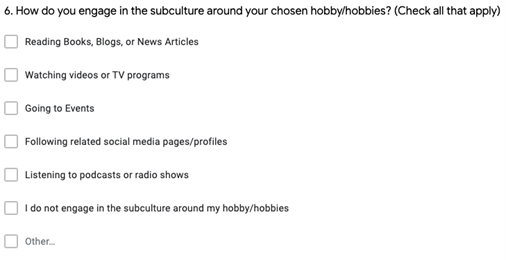

Figure 5

Question 6: How do you engage in the subculture around your chosen hobby/hobbies? (Check all that apply)

(Answered by 15 participants)

The most popular way that students enjoyed the subculture around their hobbies was through watching TV programs and videos or following related social media accounts. Both options were selected by 80% of the students (12 participants). Another option that was commonly selected was reading books, blogs, or news articles with 73.3% (11 participants) reporting reading as a way to engage with their hobby on a deeper level. Other subculture elements selected were 53.3% (eight participants) mentioning listening to podcasts and 26.7% (four participants) enjoying attending related events. The answers to this question demonstrated that each student engaged with the subculture of their hobby/hobbies, mostly through digital means.

Question 7: Based on your answer to question 6, how many hours do you spend engaging in the subcultures(s) of your hobby/hobbies?

(Answered by 15 participants)

The majority of participants (10 participants) answered that they spend less than or equal to an hour participating in the subculture of their hobby/hobbies. One-third of students (five participants) said they spend two to three hours engaging in the subculture(s) of their hobby/hobbies. While every student acknowledged participating in the subculture around their chosen hobby/hobbies, that participation was far more limited than time spent doing schoolwork or enjoying the hobby itself.

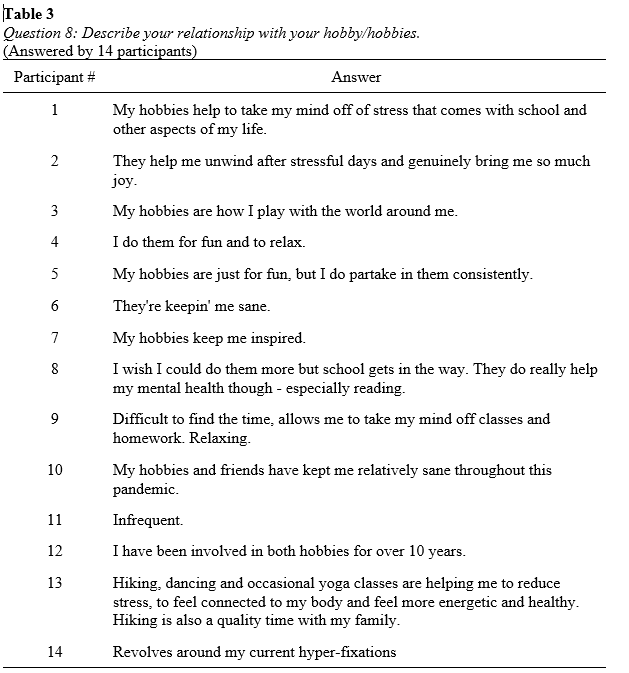

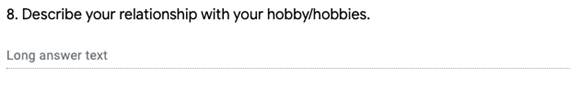

Table 3

Question 8: Describe your relationship with your hobby/hobbies.

(Answered by 14 participants)

Since question eight was open-ended, participants could skip the question if they chose to. One person chose not to answer this question, so only 14 responses were collected for question 8. Just over 78% of students (11 participants) mentioned some form of positive relationship with their hobbies, using words such as “relaxing,” “fun,” and “unwind”. Many of the answers listed above connect hobbies as an outlet for dealing with stress (see Table 3).

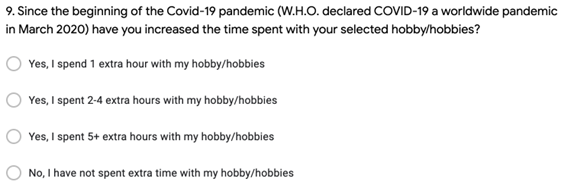

Figure 6

Question 9: Since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic (W.H.O. declared Covid-19 a worldwide pandemic in March 2020) have you increased the time spent with your selected hobby/hobbies?

(Answered by 15 participants)

Since the beginning of Covid-19, 40% of students (six participants) reported that they saw no increase in time spent with their selected hobby/hobbies. One-third of the students (five participants) said they have spent an extra two to four hours on their hobby/hobbies during the pandemic. Lastly, 26.7% (four participants) said they have increased their participation in their favourite hobby/hobbies since March of 2020.

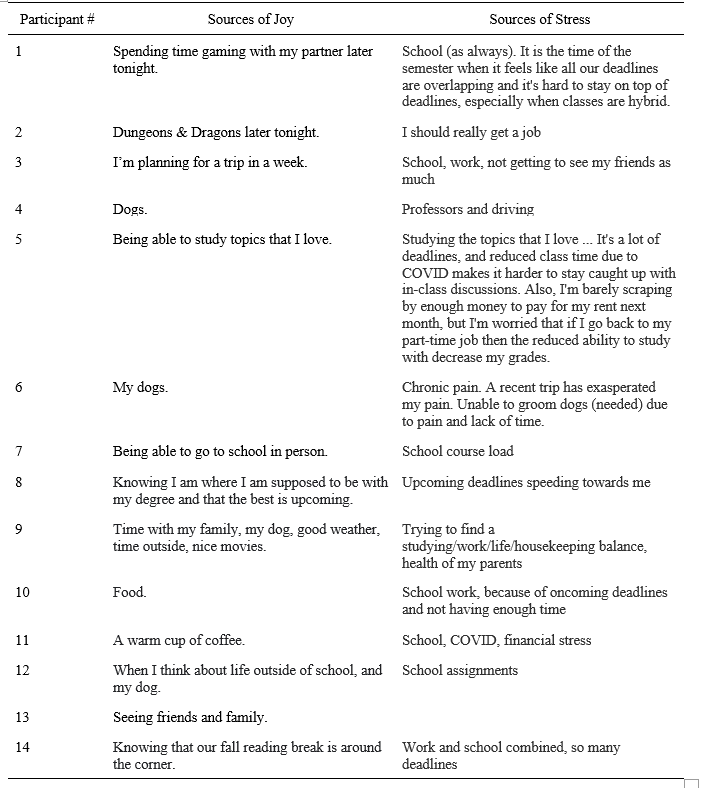

Table 4

Question 10: What is bringing you joy today?

Question 11: What is bringing you stress today?

(Answered by 14 participants)

Hobbies were unanimously established as a source of joy among the students surveyed in question 15; however, three participants actually mentioned their chosen hobby/hobbies when asked what brings them joy in question 10. Instead, responses ranged from food and coffee, to trip planning, to spending time with loved ones. Few participants had similar answers to one another, showing that sources of joy can vary from person to person more than stressors. Additionally, some of the answers provided could reflect what brought participants joy on the specific day they answered the question while other answers could reflect what brought participants joy during the more general time period around the research.

School/studying was represented in the responses of 11 participants as a primary source of stress (see Table 4). Other stressors listed were financial and work-related, usually in combination with school. Considering the target demographic, school was an unsurprisingly common stressor. The data from question eight established hobbies as an important element of a student’s lifestyle to manage the stress they experience from school.

Question 12: Does your hobby/hobbies contribute to your stress?

(Answered by 15 participants)

Two-thirds of the total participants (10 participants) said their hobby/hobbies do not contribute to their stress. Only 33.3% (five participants) acknowledged stress resulting from their hobby/hobbies.

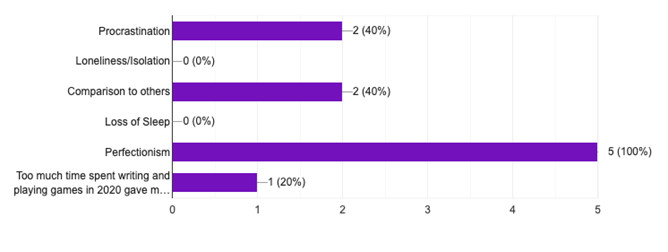

Figure 7

Question 13: If you answered “yes” to question 12, how has your hobby/hobbies related to your stress? (select all that apply)

(Answered by five participants)

Since only five of the 15 students reported that their hobbies contribute to their stress, only five people answered question 13. Everyone who did respond to this question identified perfectionism as the main source of stress coming from their hobby/hobbies. Forty percent (two participants) reported that procrastination and comparison to others from their hobby/hobbies brought them stress as well. No one reported a loss of sleep or loneliness as a contributor to their stress; however, one person did respond to the “other” option by mentioning that spending too much time on their hobbies caused an injury that still results in physical pain.

Question 14: Do your hobbies bring you joy?

(Answered by 15 participants)

Out of the 15 students surveyed, this question was unanimous: 100% of participants said yes, their hobbies bring them joy.

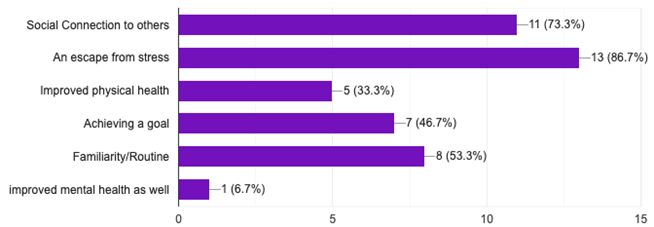

Figure 8

Question 15: If you answered “yes” to question 14, how has your hobby/hobbies brought you joy? (select all that apply)

(Answered by 15 participants)

Every participant reported that their hobbies brought them joy. Out of those responses, 86.7% of the students (13 participants) acknowledged their hobbies helped them escape from stress which was the number one contributor to their hobby-related joy. More than 73% (11 participants) mentioned that social connection contributed to their joy. Also, 53.3% (8 participants) answered that familiarity/routine brought joy. One participant filled in the “other” answer to say that their hobby improved their mental health.

Figure 9

Question 16: How would you describe your overall life satisfaction?

(Answered by 15 participants)

The most common response to question 16 had 40% of students (six participants) saying they had a good overall life satisfaction. The second-largest response consisted of a tie between “Great” and “Okay”, both at 26.7% each (four participants). No one said their overall life satisfaction was bad but one mentioned that “It varies on the day” and that they were “Incredibly satisfied with where [they were].” The statistics showed that generally speaking, students viewed their overall life satisfaction as positive.

Discussions, Conclusions and Recommendations

Introduction

This current study examined the impact of hobbies on the mental health of university students. This section used the data from the study to discuss conclusions from the research and recommendations for future research. The conclusions discuss the most popular hobby types, the sources of joy and stress that hobbies bring to participants, and how participants reported their overall life satisfaction. The recommendations section looks at ways to continue and improve the research performed in this study to better define students’ relationships with their hobby/hobbies.

Discussion

This current study determined that all participants’ hobbies bring them joy. Individual and team sports, reading, and electronic content were some of the most common hobbies listed by those who experienced joy without reporting any hobby-related stress (see Table 2). Therefore, this study concluded that physical, logical, and electronic hobbies (in moderation) are most associated with bringing people joy. This conclusion confirmed that physical activity can have a positive impact on one’s mental health (Ng et al., 2021; Pressman et al., 2009).

However, the subjective nature of hobbies made it difficult to categorize all aspects of a hobby into one specific type. For example, a hobby like videography incorporates electronic, logical, artistic, and physical elements during the production process. In the context of this current study, videography was categorized under the artistic hobby type (see Table 2), because videography involves a high level of creative thinking. Simply categorizing it as creative does not account for the different components of the activity. Additionally, this research did not consider the limitations of the four hobby types. One of the students mentioned important relationships as one of their hobbies (see Table 2). This response was marked as ‘other’ since it did not fit with the four main hobby types. The answer warrants creating a new ‘social’ hobby type since it does not seem to involve anything artistic, physical, logical, or electronic based.

When students described what about their hobbies brings them joy, the majority stated that they provide an escape from stress and social connections (see Figure 8). It was interesting to note that students associate joy with getting away from something rather than directly associating joy with the hobby itself. Additionally, when asked what brings people joy, hobbies were rarely mentioned in the responses (see Table 4). Instead, things like food, coffee, or spending time with loved ones were mentioned. There was no consistent trend in the answers to the question of what brings people joy. Although hobbies may bring someone joy, people may not associate their favourite activities with joy when asked directly (see Table 4). It is reasonable to conclude that people associate hobbies with an escape from stress rather than something that causes joy.

While the participants’ responses provided information about why certain hobbies are chosen by students, there were few answers provided regarding an emotional connection between the students and their favourite activities. It may be easier to connect hobbies with mental health by establishing the feelings that people have when they participate in those hobbies. Question eight asked how participants view their relationship with their hobby. However, some answers were too general to understand the true nature of that relationship. For example, one person described their relationship with their hobby as “infrequent” which does not highlight any emotional connection to the hobby. Gathering emotional responses would allow for a better understanding of the impact people’s favorite hobby/hobbies have on them. Emotional responses could also provide more context into the participants’ overall mental health.

In the answers to question 12, five participants reported that their chosen hobby/hobbies bring them stress. The people who acknowledged stress as a result of their hobby/hobbies listed activities that mostly fit under the categories of artistic and electronic, such as video games, creative writing, and cooking (see Tables 2 & 4). One conclusion in this current study is that artistic and electronic hobbies are more likely to bring stress. This conclusion is consistent with previous research on the mental health impacts of electronic hobbies (Ali et al., 2021; Twenge & Farley, 2020).

When asked about the stresses related to their hobby/hobbies, every participant answered that perfectionism was a contributing factor (see Figure 7). For the purpose of this study, perfectionism describes additional pressures associated with chasing a desired “perfect” result in someone’s hobby. For example, one of the participants who mentioned that their hobbies bring them stress listed playing the violin as an activity they participate in (see Table 2). Stress caused by perfectionism might consist of potentially unrealistic expectations that are difficult to realize. This study concludes that while hobbies bring people joy, there are still elements of pressure within those tasks that contribute to stress.

This current study aimed to determine whether enjoying a specific hobby would also lead to participating in the subculture around that hobby (see Figure 5). Furthermore, this study sought to examine how people engage in the subculture(s) of their hobby/hobbies and to what extent this participation occurs. Every participant stated they engage in the subculture of their hobby/hobbies to some degree (see Figure 5). However, in question seven, people reported spending more time on their favourite hobby/hobbies than following the subculture around that hobby. The extent to which someone enjoys the subculture around their chosen hobby varies, but enjoying a hobby also involves participating in the hobby’s subculture.

The number of reported hours spent engaging in the subculture of a hobby/hobbies was less than expected. Most responses to question seven reported spending less than or equal to one hour on subculture-related activities. In comparison, over 50% of participants reported spending between two to five hours per day enjoying their favourite hobby/hobbies (see Figure 3). This is interesting because, in some cases, engaging in the subculture around a hobby might be easier than participating in the hobby itself. For example, playing a game of basketball could take a couple of hours and require physically going to a gym to participate. Watching highlight videos of basketball stars like Stephen Curry or LeBron James, on the other hand, requires very little effort because of the ease of access provided by phones, computers, or TVs. Therefore, for certain hobbies, it is possible that someone could spend more time engaging in a subculture than the actual hobby/hobbies. Perhaps participants are unconsciously engaging in their hobby’s subculture without even realizing it. An individual may participate in basketball and engage in the subculture by following a celebrity like LeBron James. However, they could be following LeBron for his starring role in Space Jam or his funny tweets, rather than his accomplishments as a basketball player. Therefore, if people unconsciously do not realize they are participating in a subculture, they may be spending more time participating in their hobby/hobbies than they think. Additionally, it is possible that activities associated with a hobby’s subculture could be considered an entirely separate hobby. The final aspect of subculture(s) to consider is different levels of engagement and the impact on the relationship with their hobbies. Someone who casually enjoys their hobby/hobbies would participate very differently from someone who considers themself an enthusiast. This study does not dive deeper into the levels of engagement that people have with their hobbies and subcultures; therefore, there is no way to differentiate between casual and dedicated participants.

The final question in the survey asked about participants’ overall life satisfaction. The most popular answer revealed that students had good overall life satisfaction (see Figure 9). However, using general terms like good, okay, and great did not provide a clear picture of how participants really viewed their lives (see Figure 9). The terms used in the question were akin to routine responses that people might use in a general conversation to evade giving a real answer. For example, people who answered that they were okay with their lives could mean that they have either a positive or negative life satisfaction. Without follow-up questions to glean more information, the responses are too vague to know how people’s hobbies and lifestyles contribute to their overall life satisfaction. A better approach for asking this question would be to consider changing the question to a long answer format or changing terminology in the answers to provide clearer responses. Those answers might consist of responses like “could be better” instead of “bad” or “I feel happy where I am right now” instead of “great”.

Recommendations

This current study explored the connection between hobbies, mental health, and university students. There is still a significant opportunity for further exploration of the subject matter. Since hobbies are so subjective and unique, it would be impossible for any study to factor in every potential hobby. The four types in this study (see table 1) provide a general framework to categorize hobbies, but more detail could be useful.

One possible way to gain more information about people’s chosen hobby/hobbies is to do research through interviews and unobtrusive observation. An online survey could be impersonal and rely heavily on participants to self-report information about their lifestyles for the data to be completely accurate. Interviews allow for the researcher to be in the room with the participant and have the flexibility to ask potential follow-up questions if they are unsatisfied with the depth or quality of an answer. This would result in better qualitative information when researching emotional connections between a student and their hobby/hobbies. Unobtrusive observation would also allow the researcher to sit back and watch someone participate in their hobby/hobbies and make their own observations of the participants’ lifestyle to compare it to the information gathered in the interview. Taking a more personal approach to the connection between hobbies, mental health, and university students would allow for more accurate data.

An area for future study into hobbies is to collect more information on the hobby/hobbies themselves. Gathering data on what one’s participation in their hobby/hobbies looks like, their emotional connection to the hobby, and their level of participation would allow for a better understanding of people’s unique relationships with their hobby/hobbies. This current study did not account for the unique ways that people experience their hobbies; therefore, it limits the ability to analyze participants’ overall relationship with their hobby/hobbies. Studying how students experience their hobbies could establish a better view of their lifestyle. Future research should also consider the creation of more hobby types to categorize more activities. For example, adding a social hobby type or placing one activity into multiple hobby types, as mentioned with videography, would help detail the connection that hobby types have with mental health.

The terminology within specific questions in this survey led to vague responses that did not effectively answer some of the study’s research questions. More specifically, asking students to label their overall life satisfaction as good, bad, or okay does not provide much detail into how the participant may actually feel (see Figure 9). The language used in future survey questions should encourage participants to express as much detail as possible and in their own words. When people rate their life satisfaction, the question should either be left open-ended or have answers that depict how the participant may feel.

Lastly, there is a greater depth of analysis needed on the relationship between hobbies and the subculture of hobbies. Hobby subcultures could be examined in a separate study that analyzes casual participation versus enthusiastic participation or how those subcultures affect the relationship individuals have with their respective hobbies. This current study investigates the time spent within hobby subcultures and the different types that exist, but defining what subculture participation looks like would help participants see how much time they actually spend in their hobby’s subculture. Comparing the different characteristics of hobby subcultures, such as the motivation behind joining certain groups and how someone participates in subcultures, would highlight the dedication or relationship one has with their hobby.

References

Ali, A., Siddiqui, A., Arshad, M., Iqbal, F., & Arif, T. (2021). Effects of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on lifestyle and mental health of students: A retrospective study from Karachi, Pakistan. Annales Médico-Psychologiques, Revue Psychiatrique. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2021.02.004

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, D. J. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dictionary. (n.d.). Artistic. In Dictionary.com dictionary. Retrieved [November 25, 2021], from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/artistic

Dictionary. (n.d.). Electronic. In Dictionary.com dictionary. Retrieved [November 25, 2021], from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/electronic

Dictionary. (n.d.). Logical. In Dictionary.com dictionary. Retrieved [November 25, 2021], from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/logical

Dictionary. (n.d.). Physical. In Dictionary.com dictionary. Retrieved [November 25, 2021], from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/physical

Ng, S. S., Leung, T. K., Ng, P. P., Ng, R. K., & Wong, A. T. (2020). Activity participation and perceived health status in patients with severe mental illness: A prospective study. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 30(4), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.12809/eaap1970

Pressman, S., Matthews, K., Cohen, S., Martire, L., Scheier, M., Baum, A., &; Schulz, R. (2009). Association of enjoyable leisure activities with psychological and physical well-being. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(7), 725–732. http://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181ad7978

Twenge, J. M., & Farley, E. (2020). Not all screen time is created equal: Associations with mental health vary by activity and gender. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01906-9

Whitehead, B. R., & Torossian, E. (2020). Older Adults’ Experience of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Stresses and Joys. The Gerontologist, 61(1), 36–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa126

Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of Habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67(1), 289–314. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033417

Appendix A

Google Forms Online Survey

Figure A1. Survey question one and response options.

Figure A2. Survey question two and response options.

Figure A3. Survey question three and response options.

Figure A4. Survey question four.

Figure A5. Survey question five and response options.

Figure A6. Survey question six and response options.

Figure A7. Survey question seven and response options.

Figure A8. Survey question eight.

Figure A9. Survey question nine and response options.

Figure A10. Survey question ten.

Figure A11. Survey question eleven.

Figure A12. Survey question twelve and response options.

Figure A13. Survey question thirteen and response options.

Figure A14. Survey question fourteen and response options.

Figure A15. Survey question fifteen and response options.

Figure A16. Survey question sixteen and response options.