How Covid-19 Affects the Mental Health of Restaurant Employees (Full Chapter)

Christine O’Loughlin, Frank Scholten, Val Swanson

Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic has created and continues to create far-reaching challenges for individuals in all walks of life. In addition to pronounced health risks, the pandemic has also exacerbated other challenges such as employment security and income. Drawing on the work of Taylor et al. and Park et al., the researchers seek to understand how Covid-19 has affected the mental health of workers in the restaurant or foodservice industry. To understand the full scope of the issue, a number of questions are addressed. What stressors do workers commonly face in the industry? What stressors are most closely linked with the Covid-19 pandemic? Who is most likely to be affected? What is being done to moderate stress? This current study uses a survey to evaluate stress among restaurant workers in Edmonton, Alberta. By creating comparative indices for various stressors, it is found that the Covid-19 pandemic has not merely worsened characteristic industry stressors but has completely changed the stress landscape for many restaurant employees.

Keywords: Mental health, restaurant, employees, Covid-19, stress, depression

Introduction

Statement of the Purpose

Mental health has been an ongoing issue in the restaurant industry, and the additional stress of working through the Covid-19 pandemic has made the situation more severe. Currently, there is a lack of understanding and research about the toll of Covid-19 on mental health—especially as it concerns restaurant industry workers. Some studies have reported that up to 85% of restaurant employees suffer from depression and up to 73% suffer from anxiety (Kinsman, 2016, paras. 43–44). It is vital that the causes and effects of work-related stress in the restaurant industry are understood.

The topic of this research is mental health. More specifically, how has working at a restaurant during Covid-19 had distinguishing effects on individuals’ mental health? Who is likely to be affected? Is there a specific position related to higher stress? And what is being done to help moderate the effects of stress?

Significance of the Study

The younger generations of 2021 face higher rates of mental health complications. For those born from 1995 to 2015, the rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide are higher than other generations (Gillihan, 2019, para. 1). In many cases, the rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide attempt rates in undergraduate students have doubled from 2007 to 2018 (para. 1). Taking those numbers into consideration, along with the current state of mental health in the restaurant industry, only makes the present study more significant.

The restaurant industry is in a crisis and working in it is challenging. An article from Insider mentioned that, according to Black Box Intelligence, turnover has elevated over pre-pandemic levels (Meisenzahl, 2021, para. 2). From a survey of 4,700 former, current, and hopeful restaurant workers, turnover for hourly workers is at 144% for quick service restaurants compared to 135% in 2019, and full-service restaurants saw an increase of 106%, compared to 102% in 2019 (para. 2). Over half of workers (62%) reported receiving emotional abuse and disrespect from customers (para. 3). Furthermore, many restaurant workers in North America rely on tips to supplement minimum wage. Finances are a concern for those affected by government measures, such as lockdowns and curfews, and the uncertainty can be highly distressing (Tonon, 2021, para. 8).

Limitations

There is a lack of research concerning Covid-19, and significantly less regarding the mental health effects of Covid-19 in the restaurant industry—understandably so, given that it is an ongoing issue. Therefore, this study does not and cannot address pandemic-related contexts and experiences during or after December 2021.

Another notable limitation is logistics. Time constraints and minimal resources contribute to a limited number of participants. Furthermore, there has been significant turnover in the industry since the beginning of the pandemic, and many voices will not be heard by this study (Lorinc, 2021, para. 2).

Definition of Terms

Cope (Coping)

To deal with and attempt to overcome problems and difficulties (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2021).

Depression

A condition characterized by persistent sadness and a lack of interest or pleasure in previously rewarding or enjoyable activities (World Health Organization, n.d., para. 1).

Front of House

The part of a business where the employees deal directly with customers (Cambridge Dictionary, 2021). Refers primarily to wait staff and bartenders in the context of this study.

Mental Health

Our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Mental health affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices (MentalHealth.gov, 2020, para. 1).

Pandemic

An outbreak of a disease that occurs over a wide geographic area (such as multiple countries or continents) and typically affects a significant proportion of the population: a pandemic outbreak of a disease (Merriam-Webster, 2021).

Stressor

A stimulus that causes stress (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, 2021).

Summary

The inherent stress of working in the restaurant industry has been compounded by the complex, interconnected challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic. Through quantitative research, this study aims to clarify the impact the pandemic has had on restaurant industry workers’ mental health. The study asks the following questions: Whose mental health is most affected by the stress of working in a restaurant during the Covid-19 pandemic? Is age a factor? Which positions are the most stressful? What is being done to help those in the industry? This research is significant because it addresses mental health concerns in the workplace that have not yet been fully explored. The researchers intend for this study to increase awareness of compounding stress in the restaurant industry and encourage the adoption of preventative measures to reduce the strain on workers.

Review of the Literature

Introduction

The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her abilities, cannot cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and can make a contribution to his or her community” (World Health Organization, 2018, para. 2). What happens when individuals cannot cope with the added stresses of their lives? The mental health effects and psychological distress of being overworked and underpaid in a stressful, high-paced work environment, such as a restaurant, have been apparent predominantly in younger adults, more often in males. In undertaking this current study regarding mental health in the restaurant industry and the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic, the researchers draw upon a collection of prior research. This section examines this literature and weighs the contributions and limitations of each article.

Literature Review

COVID Stress Syndrome

To understand the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the mental health of restaurant workers, it is important to know what to expect. It is necessary to understand not only the mental health impact of Covid-19 on the general population, but also the mental health impact of working in the restaurant industry under normal circumstances. For the former, the researchers turn to Taylor et al.’s (2020) study which collected data on individuals’ Covid-19-related distress and coping mechanisms by way of an Internet-based, self-reported survey distributed in the United States and Canada (p. 707). The survey received 6,854 participants, and the results were evaluated using latent class analysis and network analysis (pp. 707–708).

The key findings of the study concern the nature of Covid-19-related distress and whether the overarching symptoms can be classified as “COVID stress syndrome” (Taylor et al.,2020, p. 713). Contrary to “recent conceptualizations,” Covid-19-related distress does not only consist of a fear of infection but a number of stressors (p. 713). Specifically, Taylor et al. identify five constituent stressors: worry about the dangerousness and rate of transmission of Covid-19, worry about the socioeconomic consequences of the pandemic, xenophobic concerns about foreigners spreading Covid-19, traumatic stress symptoms from direct or vicarious exposure to the virus, and Covid-19-related compulsive checking (news, social media) and reassurance seeking (p. 707). Furthermore, these stressors can affect and exacerbate one another. For instance, network analysis found a strong connection between traumatic stress symptoms and compulsive checking. In this example, individuals who experience greater amounts of intrusive thoughts related to Covid-19 were prone to greater amounts of compulsive checking and reassurance seeking. This increased exposure to Covid-19-related news or social media posts may, in turn, increase the number of intrusive thoughts about Covid-19, causing the cycle to repeat (p. 711).

Taylor et al. (2020) identify several limitations in their study. The noted uncertainties relate to whether or not Covid stress syndrome is its own disorder or simply a part of another, whether the syndrome is short-term or long-term, and the syndrome’s overall severity (p. 713). However, as it relates to the present study, there is another, much more obvious limitation: the time frame. Taylor et al.’s study was conducted in the very early months of 2020, having been first submitted for publication on May 12. However, global perceptions regarding the Covid-19 pandemic have shifted significantly in the seventeen months since. Unfortunately, 63% of participants that identified “reminded myself that it would soon be over” as an adopted coping mechanism (p. 709). Those seventeen months have brought with them significant challenges regarding the politicization of the virus, vaccine distribution, government mandates and regulations, healthcare strain, and constantly varying levels of infections and restrictions. Ergo, it is impossible to say that Taylor et al.’s study reflects the current state of Covid-19-related mental health concerns. However, humankind is still struggling to understand and adapt to this unfortunate reality, and as it stands, there are very few authoritative voices to turn to on the matter.

Still, Taylor et al.’s (2020) research is a reasonable contribution to the literature regarding mental health in the restaurant industry. Through the study, the fundamentals of Covid-19-related mental stress and coping mechanisms are clearer. It can be expected that restaurant industry workers in Alberta, Canada have similar concerns regarding theCovid-19 pandemic and, knowing this, the stressors unique to the restaurant industry can be isolated.

Serving Up Stress

Following the 2020 study from Taylor et al. on the typical mental health impact of theCovid-19 pandemic, it is now imperative to understand the mental health impact of working in the restaurant industry under normal conditions; Wesolowski (2016)provides an introductory overview of the issue. This study applies a qualitative approach to mental health research. Face-to-face, semi-structured interviews were conducted for a small group of participants according to Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. Fourteen front-of-house workers from Peterborough, Ontario were interviewed (p. 3).

Via Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis, four distinct meta themes were identified in the dataset. One, work stressors are emotional, physical, and organizational; two, coping is a feeling of emotional control and a way of normalizing work stressors; three, wait staff speaks about health predominantly in emotional terms; and four, wait staff internalize feelings of helplessness (Wesolowski, 2016, pp. 5–8). From these meta themes, it is clear to see that waiting tables is an emotionally laborious profession. It stands to reason, then, that the industry would be heavily impacted by the added challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic and its complex, interconnected stressors.

In addition to these larger meta themes, the smaller, more specific stressors prevalent in the restaurant industry are of note to this current study. Wesolowski (2016) identifies excessive workload, long work hours, inconsistent schedules, (perceived)shallow career development potential, customer behaviour, job performance, in- and out-groups,hierarchy, and discrimination (pp. 3–8).

Wesolowski (2016) notes two major limitations regarding her study. Firstly, none of the fourteen participants were able to be reached for follow-up interviews, thus introducing uncertainty regarding the participants’ interpretation of their experiences (p. 8). Secondly—and more noticeably—the scope of this study was very small. Given the nature of the methodology, only 14 participants were reached for interviews, and those few all came from the same city—Peterborough, Ontario. The undeniably small scope limits the study’s generalizability (p. 8). However, because the scope of the present study is also limited to a single Canadian city, it is reasonably likely that the results will reflect those found by Wesolowski. A more relevant limitation to the present study, perhaps, is that Wesolowski’s research only concerns front-of-house staff whereas the present study will accept participants from kitchen staff, managerial staff, delivery staff, and front-of-house staff. This is an important consideration as the challenges faced by kitchen staff—for example—are expected to differ greatly from those faced by the front-of-house staff. In this particular case, it is expected that front-of-house staff will perform significantly more emotional labour. By extension, it would be expected that kitchen staff and front-of-house staff respond differently to the challenges presented by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Even with these limitations in mind, “Serving up stress” is an appropriate addition to this collection of literature. In essence, Wesolowski’s (2016) efforts have established foundational expectations for the present study. Knowing which stressors are prevalent in or unique to the restaurant industry allows the researchers to better separate the effects of Covid-19 on the restaurant industry as opposed to the public in general. Furthermore, Wesolowski’s insights into the nature of mental health challenges in the industry illustrate the acute threat posed by theCovid-19 pandemic and reaffirm the importance of the present study.

Employee Work Status, Mental Health, Substance Use, and Career Turnover Intentions

Bufquin et al. (2021) explore how the shifting context of the Covid-19 pandemic has shaped worker behavior. The article notes that one of the most significant challenges the pandemic has created for restaurant employees is inconsistent operating schedules and, therefore, unstable income (p. 1). This added stress serves to exacerbate existing problematic behaviors in the industry. Prior to the pandemic, the restaurant industry ranked the highest among nineteen industries for illicit drug use and third highest for heavy alcohol consumption (p. 2). Undoubtedly, this is cause for concern, but throughout Bufquin et al.’s research, it was found that those restaurant employees who continued to work during the pandemic had higher rates of alcohol and drug use than those who were not actively working. Bufquin et al. hypothesize that fear of infection among those working and the relief of government financial aid for those who were not contributed to this discrepancy, despite previous research indicating that the reverse is true in a non-pandemic setting. Furthermore, those workers who rely on tips to supplement their wages are disproportionately impacted by inconsistent operations, limiting their otherwise more stable incomes (p. 7).

Above all, the Covid-19 pandemic has shown that life can be highly unpredictable, and restaurant workers are more likely than most to resort to destructive habits (Bufquin, 2021, p. 2). Overall, the support restaurant workers have received from their employers during the Covid-19 pandemic has not been commensurate with the added stress of this unpredictability. The restaurant industry is a difficult place to work even in the best of times, and psychological distress is a key influence in career turnover (pp. 2, 7). Exodus from any industry serves only to make that industry more difficult for those still working in it. In their conclusion, Bufquin et al. place the responsibility of mitigating stress on employers. Their recommendations include rotating which employees are furloughed, informing employees about mental health resources like hotlines, and educating employees on healthy ways to manage and cope with stress (p. 7).

An Examination of Restaurant Employee’s Work-Life Outlook

Park et al. (2021) explore how restaurant employees view their work-life balance and indicates that an individual’s support systems (both real and perceived) have a significant impact on their life satisfaction (p. 8). And indeed, Park et al. find that the amount of support an employee receives (or believes they receive) from their employer directly correlates with their current and future life satisfaction (pp. 6–7). In turn, life satisfaction influences employees’ productivity and intentions to leave the restaurant industry (pp. 1, 8). But although the study finds that those with high current life satisfaction are less likely to want to leave the industry, those with high future life satisfaction are more likely to want to leave (p. 8). The study additionally finds that individuals with high resilience (the ability to function normally when faced with adversity) are also more likely to want to leave the restaurant industry. Obversely, this means that employees with low resilience and poor life outlooks are more likely to continue working in the industry. It is these people, of course, that are most in need of social and organizational support systems. And as previously established, the Covid-19 pandemic heavily strained those few support systems that were already in place (p. 9).

Like Bufquin et al. (2021), Park et al. (2021) also close their study with practical recommendations for the industry (p. 9). These recommendations include training managers to be more supportive of employees by setting realistic goals, being a good role model, and so on. They also include more tangible strategies, such as implementing wellness programs and paid vacation time, conducting on- or off-site fitness and team-building exercises, and seeking employee input when implementing new policies and procedures. Overall, employers should seek to improve employee life satisfaction because it will contribute to organizational citizenship and loyalty among the other, more obvious benefits (p. 9).

Contribution This Study Will Make to the Literature

The Covid-19 pandemic has and is continuing to create new situations and issues that the world has never seen before, and researchers in all fields are scrambling to study and document its effects—both long- and short-term. Nevertheless, it is clear that the Covid-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the restaurant industry. The purpose of this current study is to examine, specifically, the relationship between Covid-19 stressors and restaurant industry stressors. It is imperative that the mental health of restaurant industry workers is included in the Covid-19 literature.

Review of the Problem

Mental health is a serious issue that has come to the forefront of societal woes during the Covid-19 pandemic. Upon assessing the restaurant industry, it has become apparent that the distress caused by the pandemic is exacerbating the mental health challenges already present in the industry. There is a clear lack of research into the compounding of these problems and how restaurant workers (and the industry at large) are coping with them.

Methodology

Research Methodology

For this research study, the researchers used a quantitative method for researching the mental health of restaurant employees. A quantitative method emphasizes the objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through tools like polls, questionnaires, and surveys (Babbie, 2010). An online survey was chosen as this study’s research method.

Design

A survey was developed and posted online on the “MacEwan Used Book Exchange” Facebook page and “Harts Team” WhatsApp chat. The survey consisted of 12 questions about mental health in the restaurant industry and demographic information and was open to participants from October 22, 2021, until November 5, 2021.

The study was made to be an unobtrusive analysis and only asked for anonymous feedback. Anonymity was critical to ensure that no participants felt anxious about giving answers that could result in social or economic distress if made public. Google Forms was the tool used to administer the study.

Sample

The survey was distributed on social media through private groups. The study’s target demographic was a very particular group of people—restaurant industry workers in Alberta. The online communities with the highest concentration of these individuals are all private communities; therefore, the pool of potential participants in the study was relatively small. The distribution locations were chosen primarily for their availability to the researchers.

Instrument Used

A 12-question survey is the instrument used in this current study. The topics that the survey address is listed below. Some topics are covered by one question whereas others are covered by two.

Survey Questions About Mental Health in the Restaurant Industry

Data Collection

The survey was posted to the distribution locations on October 22, 2021 and was reposted twice over the following two weeks. The survey closed on November 5, 2021. Afterward, the survey responses were compiled and organized automatically. No personal information was collected.

Data Analysis

To investigate the mental health of restaurant workers during the pandemic, the researchers examined multiple factors. A number of stress indices (SIs) were created based on participants’ responses and compared. The results were charted for convenient visualization and the compiled data was examined for correlations. These indices are discussed more deeply in the Conclusions section.

Results

Introduction

The survey consisted of 12 questions in three main sections: questions about demographic information, work-related stressors, and mental health perceptions. The survey was open to restaurant workers of all kinds, so long as they had worked in the industry before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. Participants who answered “No” to either Question two or Question three, which verify this, did not have their responses included in the data analysis process.

Of the 12 questions, 11 asked participants to choose an answer from predefined selections; however, questions were outfitted with ”Other” and “Prefer not to answer” options wherever possible. The final question regarded work-related stress management and asked participants to describe their coping mechanisms in their own words. This question was optional and received only 22 responses out of 34 total participants. The only other optional question was Question eight, regarding workplace satisfaction, which received a response from all 34 participants.

Summary of the Data

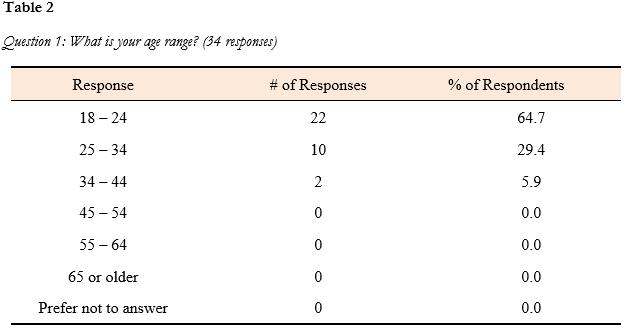

The first question asked participants for their age range. The intent of this question was to identify whether age affects reported stress levels in the Albertan restaurant industry. Out of 34 participants, 22 (64.7%) were aged 18–24, 10 (29.4%) were aged 25–34, and two (5.9%) were aged 35–44.

Question 2: Did You Work for a Restaurant in Alberta, Canada Prior to the Covid-19 Pandemic? (34 Responses)

All 34 participants indicated that they worked in a restaurant in Alberta prior to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Question 3: Have You Worked for a Restaurant in Alberta, Canada Since the Beginning of the Covid-19 Pandemic? (34 Responses)

All 34 participants indicated that they worked in a restaurant in Alberta during the Covid-19 pandemic. Questions two and three were key demographic questions. The central question of this study concerned a change in the mental health of restaurant workers since the pandemic. Therefore, those who did not work before the pandemic or have not worked during the pandemic were not eligible participants for this survey.

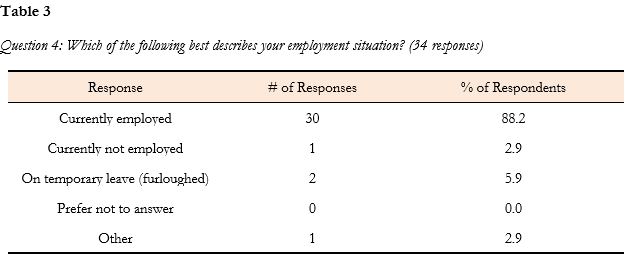

Question four established participants’ employment status. Participants who reported less desirable conditions were expected to experience issues related to income and career development. Question four received one “Other” response, which was specified as follows: “Not getting shifts and quitting soon.”

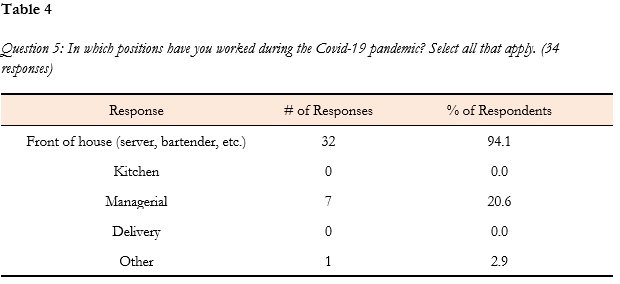

Question five indicated which positions participants have worked in during the pandemic. This allowed the researchers to make assumptions and correlations based on the type of work someone performed within a restaurant. The original intent was for this survey to be generalizable to the Albertan restaurant industry as a whole, but the reality is that it failed to reach kitchen and delivery staff. Without these key demographics, the results of this study can, at best, only be generalized to front-of-house staff in Alberta. Question five received one “Other” response, which was specified as follows: “McDonald’s so the whole thing a staff member does like kitchen front counter (whenever the store was allowed to be open) drive thru and mccafe.”

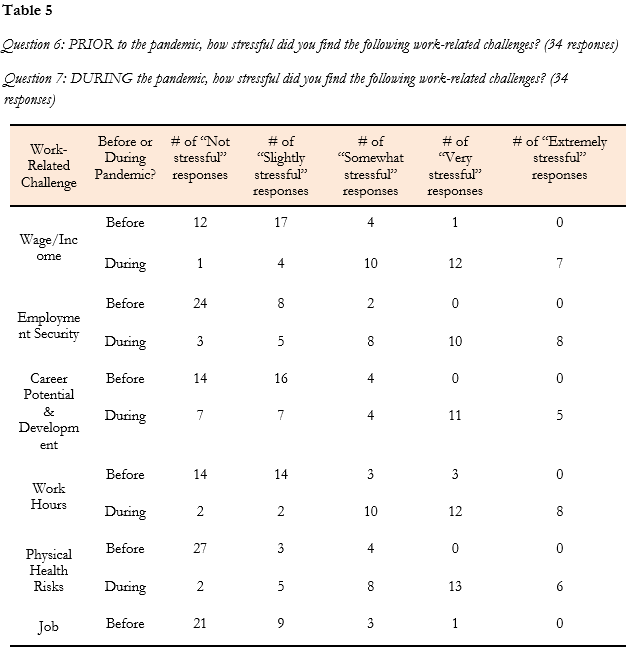

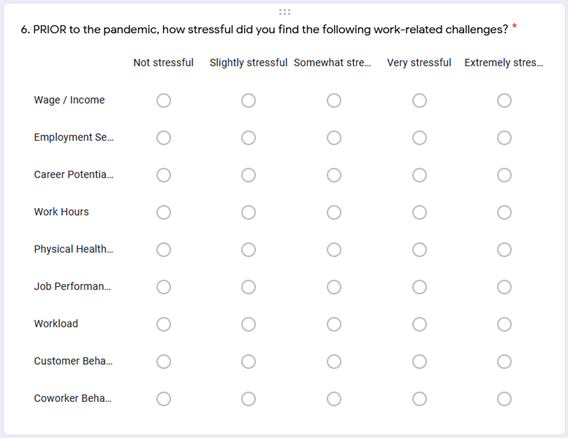

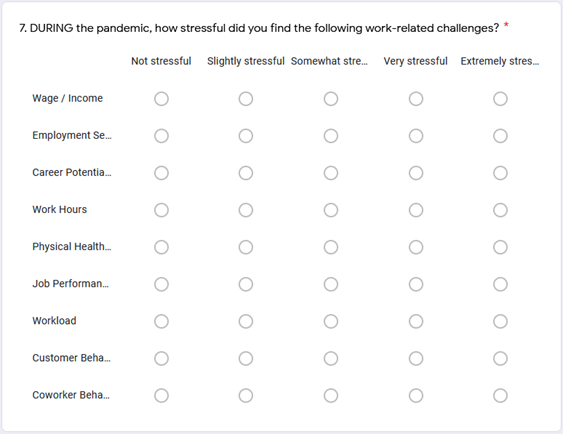

Question six measured the stress that workers were facing according to different categories relating to employment before the pandemic. This allowed the researchers to compare pre-pandemic stress levels to pandemic stress levels (question seven). It was found that EmploymentSecurity and Physical Health Risks were typically the least stressful challenges prior to the pandemic, while Workload and Customer Behavior were the most stressful.

Question seven measured the stress that workers were facing according to different categories relating to employment during the pandemic. When comparing the results to those of question six, it became clear that the stresses experienced by restaurant workers during the pandemic were more complex than a simple fear of infection. It was also found that, although they had become more stressful overall, Job Performance, Workload, and Coworker behavior contributed to stress levels less than other challenges during the pandemic.

Figure 1

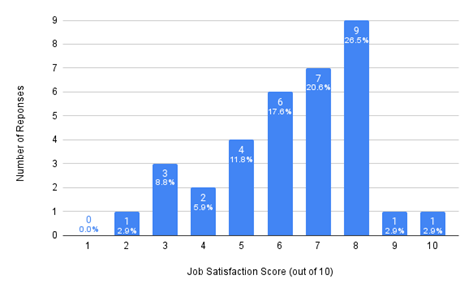

Question 8: How would you rate your overall job satisfaction? (34 responses)

Question eight asked participants to consider their overall job satisfaction—zero is considered ‘very unsatisfied’ and ten is considered ‘very satisfied’. A wide range of responses were given, but most participants reported being somewhat satisfied. The average rating was approximately 6.32 / 10.

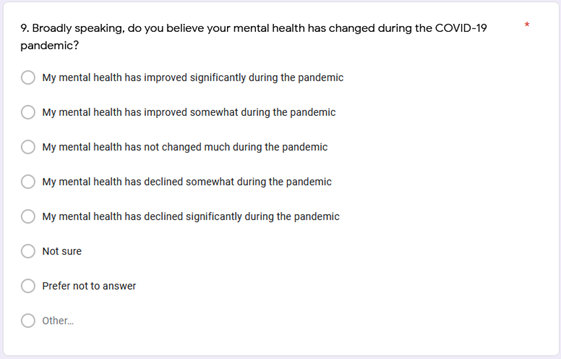

Question nine analyzed participants’ mental health and whether it has changed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. Mental health is the cornerstone of this research study and understanding how isolation and stress in the service industry impacts participants is crucial. Of 34 participants, 15 (44.1%) felt their mental health had declined somewhat, 12 (35.3%) felt their mental health had declined significantly, two (5.9%) thought their mental health had not changed much, two (5.9%) felt their mental health had improved, two (5.9%) were not sure, and one (2.9%) thought their mental health had improved significantly.

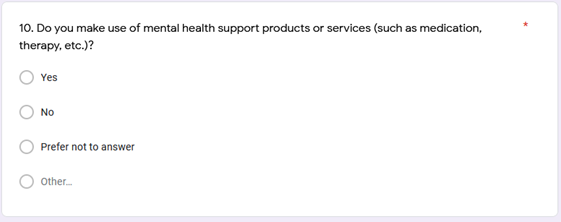

Question ten measured whether participants made use of mental health products or services. This included medication and therapy, which would help workers cope with the stresses they face. Out of 34 participants, 12 (35.3%) made use of mental health support resources, 21 (61.8%) did not make use of mental health support resources, while one (2.9%) preferred not to answer.

Question 11 asked whether a participant’s employer covered mental health support.Due to the impactful outcome of these resources, it is important that participants knew whetheror not they had access to these benefits through their employers. Out of 34 participants, four(11.8%) responded “Yes,” 26 (76.5%) responded “No,”three (8.8%) responded “Don’t Know,” and one (2.9%)responded “Other.” The “Other” response was specified as follows: “I work part time, therefore Iam not eligible for [benefits].”

Question 12: Please Describe a Few of the Things You Do to Cope with or Manage Work-Related Stress.

Question 12 asked participants to describe a few of the things they do to cope with or manage work-related stress. Because this question was optional and asked participants to give a personal example, it received only 22 responses. Answers in this section included: therapy, meditation, cleaning, yoga, spending time outside, taking a bath, alcohol, shopping, studying, marijuana, and sleep. The most common responses were those that involved socializing, relaxing, or consuming substances like alcohol. For a complete list of responses, refer to Figure B12 in Appendix B.

Conclusions, Discussions, and Recommendations

Introduction

Mental health is an important topic of study, and the Covid-19 pandemic provides an opportunity to analyze this topic. In the restaurant industry, businesses have closed, and many employees have been temporarily or permanently laid off. As a result, stress and mental health complications are on the rise as workers struggle to adapt to and cope with the rapidly changing circumstances. The following section examines how the data reflects this reality and discusses the changes in more detail.

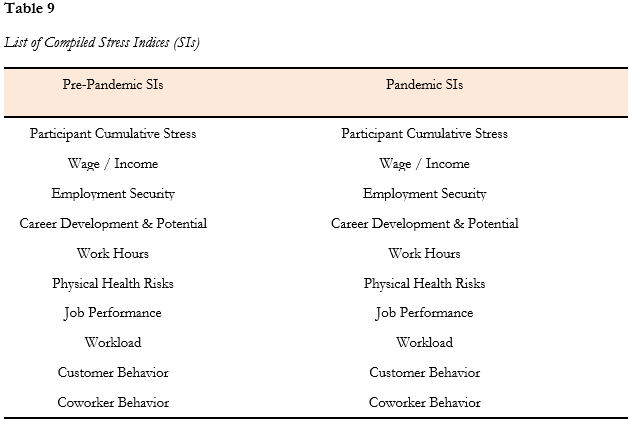

Conclusions

To analyze the survey results, researchers compared the responses to questions six and seven (Table 5). However, the data first needed to be converted into a form that could be efficiently analyzed. To do so, each potential response was given a numerical value between zero and four with “Not stressful” being zero and “Extremely stressful” being four. The responses to the two questions were converted into integer values and totalled to create a number of stress indices (SIs) (Table 9). These indices provide approximate representations of stress levels. It should be noted that appending numerical values to what are, ultimately, subjective classifications introduce a significant margin for error. Therefore, these indices should be considered estimates rather than concrete data.

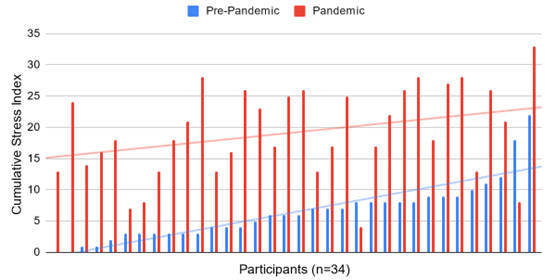

Two sets of SIs were created. The first set contains a pre-pandemic and pandemic SI for each of the 34 participants and was made using values from all work-related challenges (Figure 2). The second set contains a pre-pandemic and pandemic SI for each work-related challenge (work hours, workload, etc.) and was made using values reported by all participants (Figure 4).

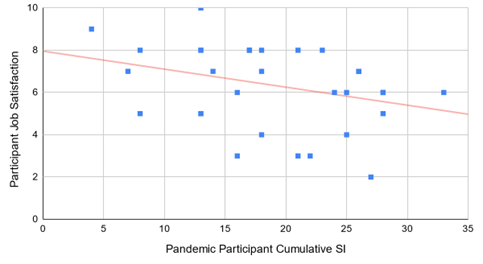

Figure 2

Comparing Participant Cumulative SIs

Figure 2 provides a visualization of the 68-participant cumulative SIs. In it, the change in participants’ overall stress levels can be seen by comparing their pre-pandemic and pandemic cumulative SIs. Figure 2 additionally illustrates how pre-pandemic stress levels correlate with pandemic stress levels via the trendlines.

It is clear that stress levels during the pandemic far exceed stress levels prior to the pandemic in most cases. This is consistent with the researchers’ expectations. However, there appears to be only a small correlation between pre-pandemic stress levels and pandemic stress levels. It was found that participants who reported high pre-pandemic stress levels were, on average, only slightly more likely to report high pandemic stress levels than participants who had reported low or moderate pre-pandemic stress. However, despite the implications of the trendlines, the actual changes in stress levels vary significantly.

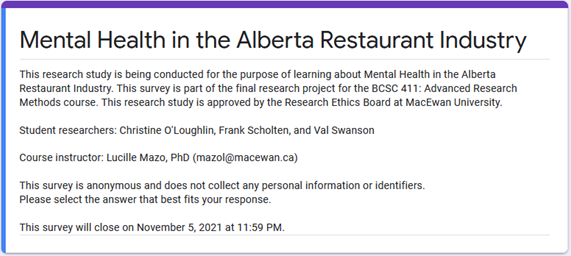

Figure 3

Job Satisfaction Rating Compared to Pandemic Participant Cumulative SI

Participants’ pandemic cumulative SIs were compared against their reported job satisfaction scores (Figure 3). It was found that job satisfaction decreased as stress levels increased. However, this was on average. In actuality, there is, once again, a diverse range of responses, indicating that there are likely other variables at play that this survey did not focus on.

However, a correlation was established between participants’ job satisfaction and perceptions of their mental health. As previously explained, the average job satisfaction score among all participants was 6.32 / 10 (see Figure 1). But among those who reported an improvement in their mental health, those who reported no noticeable change, and those who were unsure, the average job satisfaction score was 7.80 / 10—a marked increase (see Table 6).

Figure 4

Comparing Work-Related Challenge SIs

Figure 4 visualizes the SIs for each work-related challenge included in questions 6 and 7 (see Table 5). Before the pandemic, customer behavior was highlighted as the most stressful part of working in a restaurant, and this has remained true during the pandemic as well. However, the challenges that saw the largest increases in stress were physical health risks followed closely by employment security with income and work hours not far behind. The challenges that were least affected by theCovid-19 pandemic were workload and performance.

Although no benefit correlation was proven in this study, mental health issues are usually treated by making use of available mental health supports. In the survey, the researchers examined whether restaurant workers make use of mental health support. In question 10, 21 out of 34 participants reported use of mental health support products and/or services. Unfortunately, these products and services are not free, and as the researchers discovered, most employers do not provide benefits that cover mental health support. Out of 34 participants, 26 stated that their employer did not provide mental health coverage or benefits. These results are a microcosm of a worrying problem. Ensuring that employees are well taken care of and have access to mental health services is a logical way to boost morale in the workplace. Although recommended, the researchers found no correlations regarding mental health support use or knowledge of mental health benefits in this study.

Discussions

This study provided evidence that stress related to Covid-19 is more complex than a simple fear of infection. Rather, it is a complex and interconnected system of various worsening stressors. Furthermore, the pandemic has not simply made the stressors of restaurant work more pronounced, but completely changed the way employees approach their mental health (see Figure 2).

The core of this study’s results lies with the responses to questions six and seven. These questions examine nine work-related challenges: wage and income, employment security, career potential and development, work hours, physical health risks, job performance, workload, customer behavior, and coworker behavior. Together, these questions make up the Stress Index. Reported stress levels in all categories increased significantly during the pandemic, though not uniformly. One of the most noticeable results is that those stressors tied to the labour being performed (job performance and workload) were much less exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Aside from physical health risks (which were expected to worsen dramatically), the stressors that saw the most change were those associated with employment itself, including income, hours, and security. A limitation of this study is that there is a potential overlap between these stressors. For example, it is possible that participants who reported high stress due to income did so due to uncertainty about work hours. Nevertheless, the fact thatthese three stressors saw such a notable increase indicates the inability to meet their financial needs in either the short- or long-term under the current conditions of their employment which is a major concern among restaurant workers.

An interesting contrast to the findings of questions six and seven were the results of question eight. Participants’ job satisfaction was compared to their Pandemic Stress Index (see Figure 3); although it is true that higher stress levels generally corresponded to lower satisfaction, the overall satisfaction levels were high. Twenty-four out of 34 participants (70.5%) rated their overall job satisfaction as six or higher, many of whom also reported comparatively high stress levels. Clearly, there are more factors contributing to job satisfaction that this study does not account for, but the connection found between stress and job satisfaction indicates that workers may hold a range of views regarding work stress. Potential questions for future research arise. To what extent do restaurant workers perceive Covid-19-related stress to be beyond the industry control? To what extent do workers believe that high stress is an inherent part of working in the restaurant industry?

The question remains: how can conditions be improved for restaurant workers? Assuming that employers are following up-to-date guidelines on Covid-19 procedures and restrictions, there is likely little that can be done to relieve stress from physical health risks. Customer behavior, on the other hand, was already a large contributor to workplace stress priorto the pandemic. With new and confusing rules for dining, it is unlikely that this issue can be solved by management either. Instead, it would likely be more fruitful to address the stressor directly related to employment—wage, hours, and security. Greater transparency from management on topics like hours of operation, pay cuts, and lay-offs may help to lighten employee uncertainty and reduce the impact of these three key stressors. Another strategy may be to offer benefits that cover mental health support, as many participants noted a lack thereof. This solution will not be possible for all businesses but encouraging healthy coping mechanisms (such as counseling) over unhealthy mechanisms (such as substance abuse)may prevent high-stress levels from causing long-term damage to employees.

Recommendations for Further Research

This study contributes to mental health literature by examining the impact of Covid-19 on restaurant workers in Alberta. Because Covid-19 is such a recent branch of study, more work must be done before the effects are fully understood.

This study focused its research on restaurant employees in the Edmonton area only. To verify this study’s generalizability, other populations ought to be studied. Other factors may also be contributing to pandemic stress levels, notably gender and race, which this study did not explore. Finally, this study failed to reach a wide variety of restaurant workers, as was intended. In particular, no kitchen or delivery staff participated, and most of the managerial participants also reported working in the front of house. Therefore, it cannot be said that the research presented here is generalizable to the Albertan restaurant industry as a whole. At best, it is generalizable only to Albertan front-of-house workers.

References

Babbie, E. R. (2010). The Practice of Social Research. USC Libraries. https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/quantitative

Bufquin, D., Park, J.-Y., Back, R. M., de Souza Meira, J. V., & Hight, S. K. (2021). Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: An examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102764

Cambridge Dictionary. (2021). Front-Of-House. Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/front-of-house

Gillihan, S. J. (2019, December 16). Why Young People Face a Major Mental Health Crisis. Psychology Today.

Kinsman, K. (2016, October 6). Chefs with Issues: What’s killing the restaurant industry. Medium.

https://medium.com/@katkinsman/chefs-with-issues-whats-killing-the-restaurant-industr y-870e68812b8a

Lorinc, J. (2021, October 19). More than 180,000 workers have left the restaurant sector. Most have become white-collar worker —and they’re not coming back. Toronto Star.

Meisenzahl, M. (2021, October 8). Over half of restaurant workers say they’ve been abused by customers or managers—and many are planning to flee the industry because of it. Business Insider.

MentalHealth.gov. (2020, May 28). What is Mental Health? U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.mentalhealth.gov/basics/what-is-mental-health

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. (n.d). Cope. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/cope

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. (n.d). Pandemic. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pandemic

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. (n.d). Stressor. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/stressor

Park, J. Y., Hight, S. K., Bufquin, D., de Souza Meira, J. V., & Back, R. M. (2021). An examination of restaurant employees’ work-life outlook: The influence of support systems during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102992

Taylor, S., Landry, C. A., Paluszek, M. M., Fergus, T. A., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2020). COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depression and Anxiety, 37(8), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23071

Tonon, R. (2021, February 01). Pandemic Pressures: How Chefs are Coping with Mental Health. Fine Dining Lovers.

https://www.finedininglovers.com/article/chefs-mental-health-pandemic

Wesolowski, A. (2016). Serving up stress: Perceived stressors and coping mechanisms of front of house restaurant employees. Journal of Undergraduate Studies at Trent, 4(1), 706–714. https://ojs.trentu.ca/ojs/index.php/just/article/view/66

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Depression.

https://www.who.int/health-topics/depression#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2018, March 30). Mental Health.

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

Appendix A

Blank Survey

Figure A1. Survey explanation and disclaimers.

Figure A2. Survey question one and response options.

Figure A3. Survey question two and response options.

Figure A4. Survey question three and response options.

Figure A5. Survey question four and response options.

Figure A6. Survey question five and response options.

Figure A7. Survey question six and response options.

Figure A8. Survey question seven and response options.

Figure A9. Survey question eight and response options.

Figure A10. Survey question nine and response options.

Figure A11. Survey question ten and response options.

Figure A12. Survey question eleven and response options.

Figure A13. Survey question twelve and response options.